Under the North American Model of Wildlife Conservation, states play a major role in wildlife management, and for better or worse, much of their efforts have focused on species that are hunted and fished. So it’s no surprise that most of the funding for state conservation efforts is provided by a particular group of people: hunters and anglers.

Today, nearly 60 percent of funding for state fish and wildlife agencies comes from sources related to hunting and fishing. The largest portion is revenues from state hunting and fishing licenses, which combine to equal about $1.6 billion annually nationwide. In addition, revenues from federal excise taxes on firearms, ammunition, fishing tackle, and related items provide roughly $1.1 billion to state agencies each year.

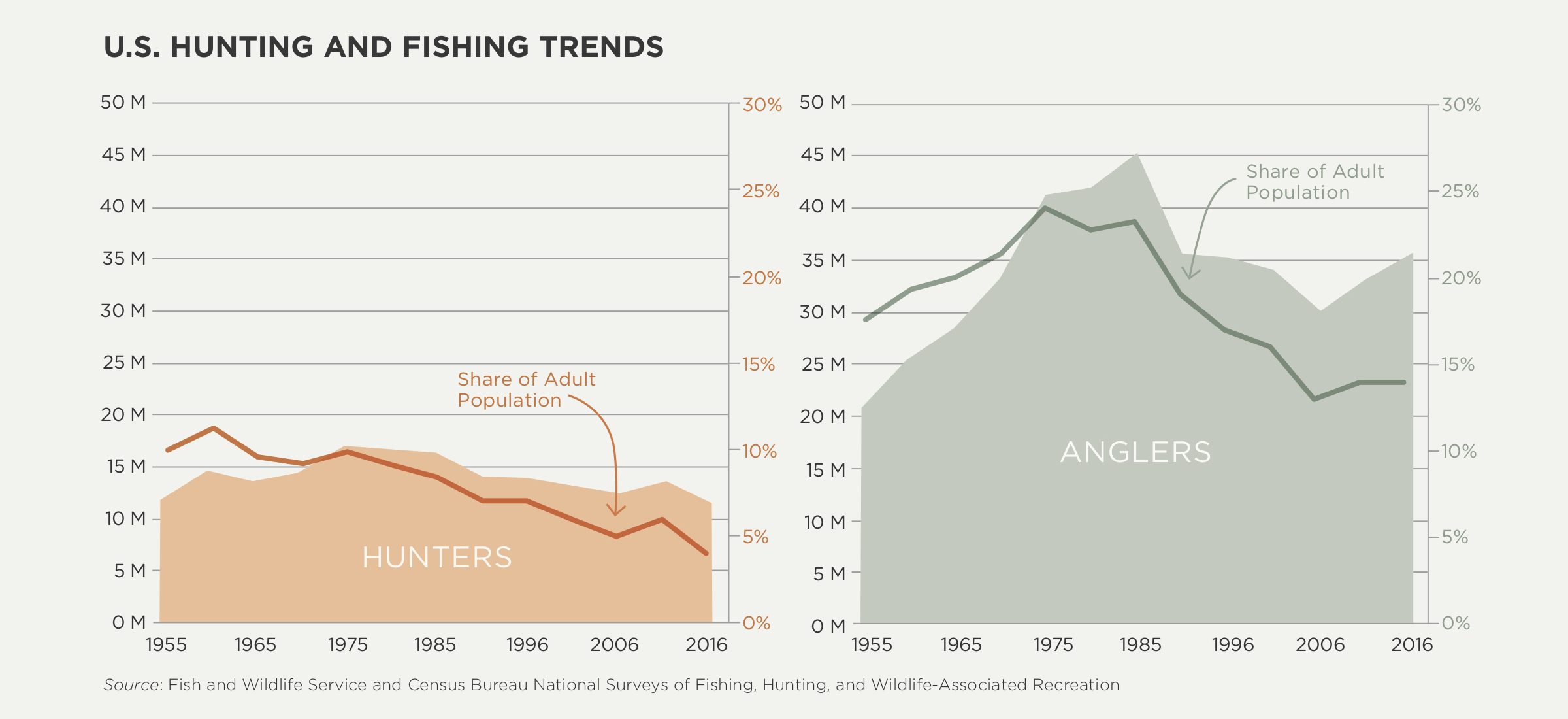

Lately, the reliance on hunting and fishing for state conservation funds has become a cause for concern given the long-term trends of those activities. The share of the adult population that hunts peaked around 1960 at 11 percent. That participation rate had fallen to 4 percent by 2016, or about 11 million hunters, a decrease of more than 2 million hunters over the previous five years. When it comes to fishing, participation peaked in 1975 at nearly one-quarter of the adult population. That rate had fallen to 14 percent by 2016, or about 36 million anglers.

So far, these declines in participation have not been reflected in the relatively stable streams of revenues that come from state licenses and federal excise taxes. One explanation is that states have become more adept at pricing hunting and fishing licenses in ways that have maintained agency revenues—such as charging more for out-of-state licenses and tags. Population growth also helps offset the decline in participation rates, making it easier for states to maintain—if not grow—their license revenues. Likewise, recent increases in excise tax revenues have been driven largely by activities not necessarily related to hunting, including growth in handgun sales, target shooting, and gun collecting.

Regardless, anecdotal evidence from state agencies suggests that long-term declines in hunting and fishing are a worry given the significant amount of funding historically derived from hunters and anglers. Whatever the future structure of the North American Model of Wildlife Conservation looks like, it will have to account for the challenges presented by a funding foundation that could be shifting in the 21st century.

Read more in PERC’s recent report “How We Pay to Play: Funding Outdoor Recreation on Public Lands in the 21st Century.”