You could argue our species needs freedom as much as we need food. The ocean provides both. It offers wide-open access to its salt spray, crashing waves, and vast mysteries beneath the surface. Far from the surf, its bounty fills our supermarkets with everything from halibut and hake, to crab and cod, salmon and shrimp, and snapper and grouper—a taste of the sea’s raw wildness.

Alas, seafood has become a victim of freedom. Open access means nearly 100 million men and women around the world can and do cast a hook or net—or, in some cases, even a homemade bomb—to capture the ocean’s bounty, whether for recreation, to harvest protein, or to earn a living. What’s more, the ocean’s “vast mysteries” are receding as innovations above its surface—including repurposed wartime technologies such as monofilament line, hydraulics, spotter planes, GPS, SONAR, LORAN, and RADAR—now allow us to penetrate its depths with pinpoint accuracy.

Year after year, fishing fleets ranging in size from outboard skiffs to floating factories extract more than 90 million metric tons of seafood, catching too much too fast for the ocean to renew itself. Such overfishing has human consequences as well. Compounded by global heating and acidification, two-thirds of all fisheries could be depleted by 2050, erasing fishing jobs and depriving billions of the nutritious animal protein.

The depletion of ocean fisheries is a classic case of the “tragedy of the commons.” Each seafood harvester understands that his actions impact his fishery and pose risks to the sustainability of it. Yet each devotes ever more time, energy, and money to his pursuit, eroding the source of his sustenance. Understandably, fishermen explain the vicious cycle with an existential shrug: “If I don’t take the last fish, someone else will.”

Fishing rights that are clearly defined, enforceable, and transferable give fishermen “skin in the game” and motivate them to leave more fish in the water today to ensure there’s an abundant and valuable harvest available tomorrow.

The standard response is to crack down. Impose abstinence. Force a kind of maritime gastric bypass surgery on human appetites. Push seafood off menus and fishermen off the sea. Even if it were possible (spoiler alert: it isn’t), shuttering the sea would diminish the health of our body and spirit—and our wildness.

Fortunately, the tragedy is not inevitable. Over several decades working in conservation, from the African desert to tropical rainforest to offshore seas, I have seen communities sustain their wild harvest by securing clearly defined rights to the natural resource on which they depend. I have watched men and women agree on rules over access to and use of the water, pasture, forest, or fishing grounds they share. Accountable rights and responsibilities foster trust and cooperation and turn scarcity into relative abundance. In recent years, such customary peer-to-peer governance systems have been adapted, formalized, and scaled with advanced technology, and commercial fishermen have led the way.

Reversing Collapse

Amid grim and noisy headlines of oceanic seafood loss, waste, and ruin comes a quiet and equally accurate story of human agency. Fishermen and policymakers are uniting to replenish the resources on which we all depend. The catalyst behind this sea change is a policy innovation known as rights-based management, or “catch shares” in the United States.

Under negotiated contracts, a government agency sets science-based limits on an overall harvest, then clearly defines for fishermen and coastal communities a portion of the catch—either as a percentage of the total harvest or a spatial share of traditional fishing grounds—in exchange for their adhering to strict accountability. These shares can often be purchased, leased, or handed down to family members, which gives them enduring value. Fishing rights that are clearly defined, enforceable, and transferable give fishermen “skin in the game” and motivate them to leave more fish in the water today to ensure there’s an abundant and valuable harvest available tomorrow.

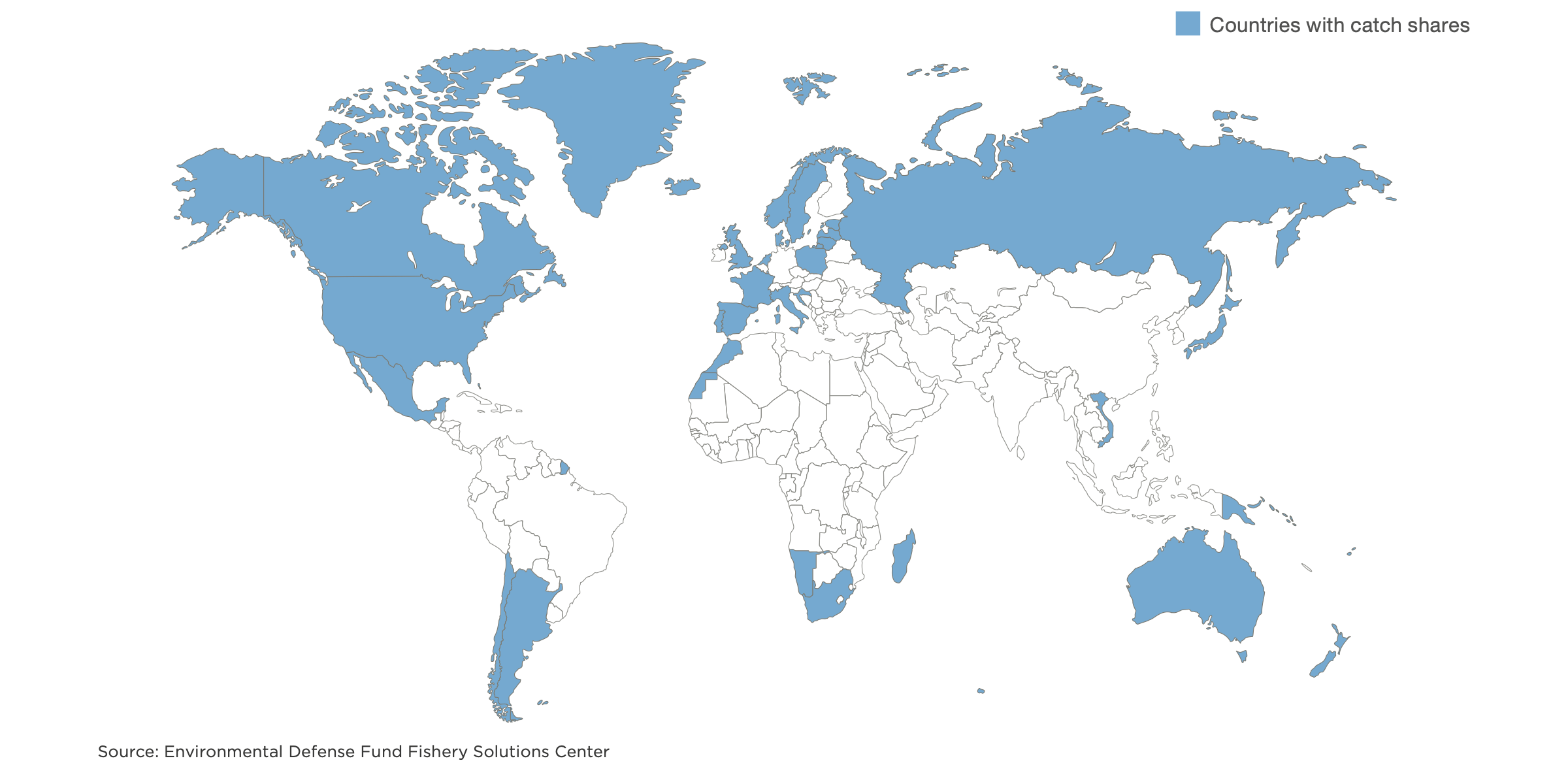

The roots of this institutional innovation spread deep and wide. Customary rules provided a foundation for rights-based fishing in numerous societies over centuries, from Fiji to Turkey. In recent years, formal versions have been enshrined in constitutions from Iceland to South Africa to New Zealand. Today, fishermen and governments have together forged more than 200 such rights-based systems, co-managing 500 different species back to health across 40 nations.

While there’s still room for improvement, this rapid, widespread, and bipartisan recovery marks the single greatest conservation triumph that almost no one has heard of.

Fishermen with these secure rights now enjoy longer seasons, safer fishing, lower costs, and higher earnings; meanwhile, the public enjoys healthier ocean biodiversity and fresher food. Catch shares offer a pragmatic blueprint that could trigger a global ocean recovery.

Too good to be true? PERC senior fellow Christopher Costello, along with his colleagues at the University of California, Santa Barbara, crunched the numbers from a global database of catch statistics that encompassed 11,135 fisheries from 1950 to 2003. They set out to “test whether catch share fishery reforms achieve these hypothetical benefits.” The data revealed that catch shares not only halt but even pull back the global trend of open-access fisheries heading toward collapse.

To Costello, this was akin to going from a monthly apartment rental to ownership of a home, even—or especially—a fixer-upper. “You take care of it—you protect your investment,” he said. “When you allocate shares of the catch, then there is an incentive to protect the stock. We saw this across the globe. It’s human nature.”

Under the Sea

From coast to coast to coast, America’s catch shares have begun to transform some of the world’s largest and smallest fisheries in both fresh and salty waters, motivating stewardship by commercial and recreational fishing vessels alike.

In just two decades, the results have been dramatic. Thanks to reforms such as catch shares, America’s fishermen have rebuilt more than 45 depleted fish stocks. Today, 91 percent of U.S. fishing stocks are either sustainable or on the path to being so, boosting the nation’s 1.7 million fishing-related jobs and $212 billion in sales that depend on coastlines teeming with life. While there’s still room for improvement, this rapid, widespread, and bipartisan recovery marks the single greatest conservation triumph that almost no one has heard of.

How did it happen? Progress has been incremental and messy. Yet if success has a thousand fathers, most of them work the ocean from the Gulf of Maine to the Gulf of Mexico to the Gulf of Alaska. Fishermen helped drive initial reforms in places such as Port Judith, Rhode Island; Galveston, Texas; Tampa, Florida; and Fort Bragg, California. Along the way, they found unorthodox allies among a handful of innovative and open-minded marine policy officials, environmental groups, and even some renegade scholars in far-away Bozeman, Montana, nearly a mile above sea level.

Fifteen years ago, I pitched up at PERC in Bozeman as a Prius-driving, Left Coast political appointee of the Clinton White House and introduced myself to a friendly gang of small-government, libertarian-minded economists who, at the time, seemed to me a bit crazy. My favorite ones still do.

I came as a participant in PERC’s Kinship Conservation Institute, which later became the PERC Enviropreneur Institute. I grew instantly immersed in vibrant—and sometimes contentious—exchanges of ideas about applying property rights and markets to environmental challenges. The intellectual friction felt wonderfully bracing, yet our clash of ideas often felt too theoretical.

Then one day Donald Leal, a PERC senior fellow, flipped on a projector and introduced us to “individual transferable quotas,” now better known as catch shares or fishing rights. I still vividly remember that lecture. It wasn’t abstract or hypothetical. It was happening. And it was as if someone threw a rock through a double-pane window.

“Rather than fight officials over how much fish they can catch, with what gear, on which days,” he explained, “fishermen now look ahead to the future value of their quota and demand lower catch limits to rebuild populations faster.” My jaw dropped. Fishermen were making more money by catching fewer fish. Rewilding the ocean was not just possible, but profitable.

Rights to wild fish made economic and ecological sense yet raised interesting political questions. Should fishermen be awarded shares based on their historic—and sometimes unsustainable—catch levels? How can new entrants break into the market? Are rights allocated by weight or percentage? Is anyone sure how fast species reproduce? Where do recreational anglers fit in? How do officials ensure compliance when hundreds of fishing boats sail in rough seas that are sometimes 200 nautical miles offshore?

Such questions often transcend peer-reviewed scholarship to engage practitioners. And, indeed, through its various programs and fellowships, many of these issues have since been raised and addressed by PERC and its associated fellows working in the field.

Thanks to this and other work, catch-share fishing rights can now be traced to an influential network that spans the ocean, rebuilding life and boosting resilience offshore. The rights-based principles I encountered in Bozeman all those years ago have begun to transform the way fisheries are managed offshore—and, as I’m discovering today, have the potential to remake the way resources are managed onshore as well.

Beneath the Ground

Humans cannot live on fish alone. Most of our drinking water and half of our irrigated food comes from groundwater. Humble, earthy, and hidden from view, groundwater feels emphatically unsexy. It lacks the romance of fishing, the jolt of energy, and the scale of climate change. Except when millions of wells run dry.

That’s not a hypothetical; it’s happening in my home state of California. Drought’s impacts are well known on the surface, as the state dammed, diked, diverted, dried, and silenced rivers in an unprecedented replumbing operation over the past century. Less appreciated, until recently, is how much urban, rural, and natural life depends on functioning aquifers.

Offshore fishing and inland farming may seem worlds apart. Yet both activities, in their own arenas, are susceptible to the tragedy of the commons. In both, cheap energy and new technologies lower the barriers to extract wealth from an invisible common pool. To slow, stop, and reverse depletion, both must find ways to share and steward this precious and literally “price-less” asset beneath the surface.

As with ocean fisheries, the typical response to groundwater depletion is to call for coercive regulations that force all users to pump less. Aside from the political obstacles, there are as many legal and practical challenges to this approach as there are wells. Without bottom-up collaboration, it will remain difficult to even figure out whose wells are pumping how much and from where, let alone force people to cut their water use.

As an alternative, today my partners and I have begun to apply the same rights-based approach to groundwater that has worked so well in fisheries. Our company, AquaShares, helps water users design and operate water savings markets in groundwater basins ranging from Sonoma County, California, to Marrakesh, Morocco. We work with communities to set collaborative goals that are fair, inclusive, and build resilience. To achieve these outcomes, we design accountable, yet flexible credit trading systems that limit market power, integrate the human right to water, ensure efficient trading, and protect groundwater-dependent ecosystems from deeply rooted forests to shallow ephemeral wetlands.

Each groundwater market platform is a blueprint, no better or worse than the values of the people who shape and adapt it to their desired outcomes. Since goals vary within and between basins, no two markets are the same. Given so many variables, and the novelty of the rights-based platform, some participants ask us: How can we be confident collaboration will work here?

One answer is that past is prologue. Those centuries-old traditional fishing systems from Fiji to Turkey laid a foundation for PERC and others to help improve the design and performance of formal catch shares. In addition to those lessons, wisdom passed down through 10,000 years of experiences in customary water allocation systems—which span cultures around the globe and whose local names include !xaro (Kalahari), aflaj (Arabian), qanat (Persian), karez (Chinese), khettara (Moroccan), and subak (Balinese)—informed the mission, work, and business model of AquaShares.

Yet in the end, the rights-based approach can only illuminate risks and rewards, like an old lighthouse or modern GPS helps vessels avoid treacherous rocks to reach safe harbor. The navigation itself remains a collaborative, iterative process. Stakeholders must still hash out details with each other in the open. With food and freedom at stake, people invariably fight with each other. They may stand up, bang the table, storm from the room. But they will come back. The ordeal is slow, messy, aggravating—and exciting.

Over the years, I’ve seen how a well-designed program of secure rights and market incentives can turn the tide at sea and beneath the ground to replenish invisible natural resources. Turning rights-based principles into policy and practice requires time, care, and energy. The transition is hard. Change always will be. But I have no doubt that it’s worth the effort. For it brings meaning and responsibility to our relationship with the wild, our ethical link that remains, as Aldo Leopold described it, “an evolutionary possibility and an ecological necessity.”