DOWNLOAD THE FULL REPORT

Summary

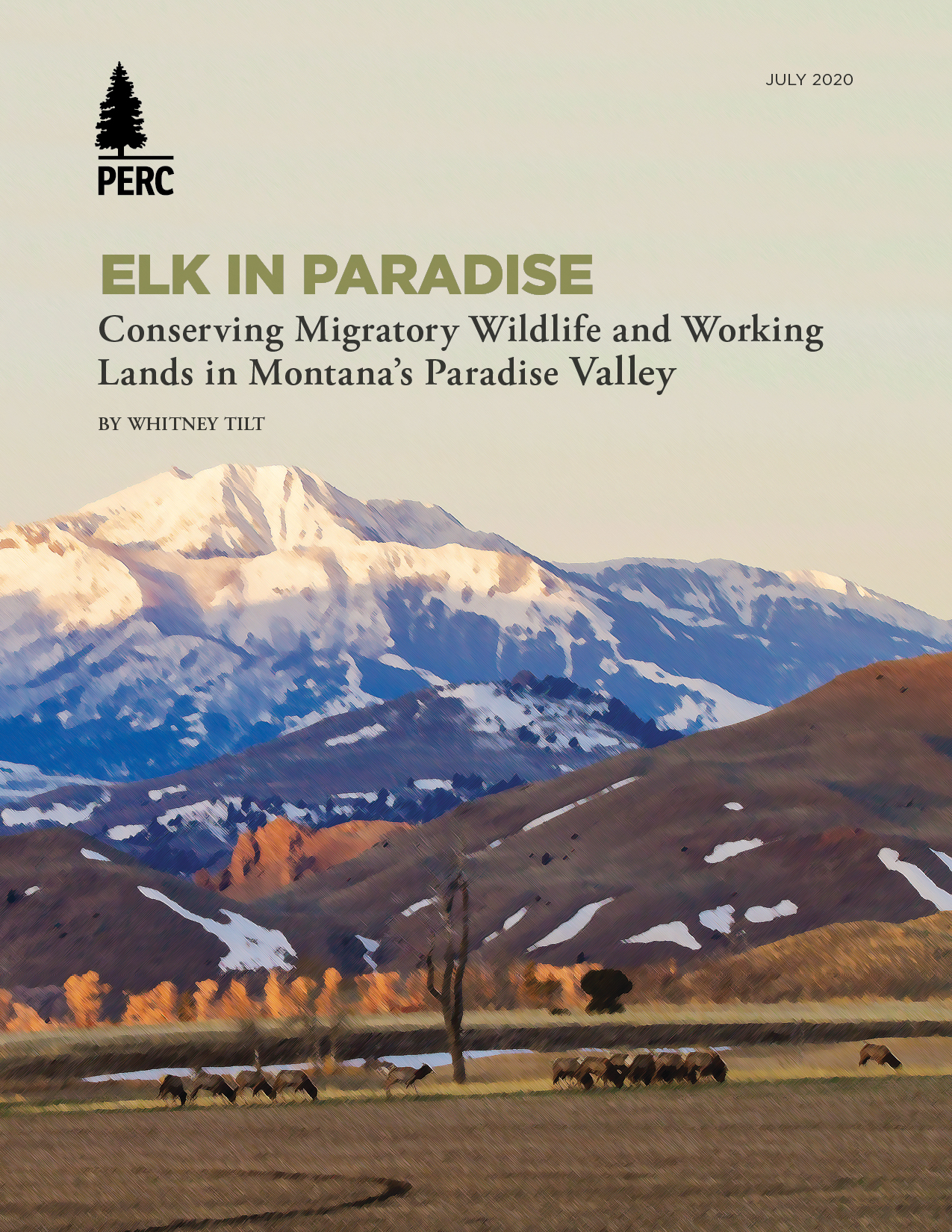

Montana’s Paradise Valley is a rural landscape with deep-rooted ranching traditions, scenic views, and ample recreational opportunities located at the northern gateway to Yellowstone National Park. Surrounded by national forest lands, Paradise Valley and its ranching community support a range of wildlife including elk, mule deer, bighorn sheep, and pronghorn antelope. The region also hosts expanding populations of gray wolves and grizzly bears.

Much of the responsibility and financial burden of providing crucial habitat for these species falls on the valley’s private landowners—yet landowners often feel their perspectives are not adequately heard. This report presents findings from an extensive survey and numerous discussions with landowners in Paradise Valley, which reveal landowner attitudes toward wildlife and point the way to solutions that can support landowners and wildlife in the valley.

Our results show that elk in particular present significant challenges for landowners in Paradise Valley—including competition with livestock for forage and hay, damage to fences, and disease transmission. As elk spend more time on private lands in the valley, and in greater numbers, tolerance often wears thin. Many landowners feel that the public benefits they provide are too often overlooked by the state and federal land management agencies, hunters, and the general public that often shape wildlife policies.

We found that Paradise Valley landowners are united in their interest in new approaches that can help preserve agricultural traditions, maintain open spaces, and conserve the valley’s private working landscapes that support agriculture and benefit wildlife. Nevertheless, many landowners are increasingly leery of the potential for regulation and loss of property rights and want solutions that preserve their autonomy and provide tangible benefits for supporting wildlife.

For wildlife proponents, the message from this report is clear: The private working lands of Paradise Valley are vital for sustaining populations of elk and other wildlife. But to ensure those lands can continue to be counted on as part of a conservation portfolio, more work is needed to embrace private landowners as full and equal shareholders in a new era of cooperation. We offer a toolkit of strategies that landowners, conservationists, and policymakers could employ to help sustain the working lands of Paradise Valley and the wildlife they support.

Recommendations

Landowner Coordination and Outreach

- 1. Establish a Paradise Valley Working Lands Group

- 2. Tell the story of ranching and recognize its benefits to community and wildlife

- 3. Engage landowners as full shareholders in wildlife management decisions

- 4. Change the message and the messenger

Financial Incentives

- 1. Work to develop a brucellosis risk-transfer tool

- 2. Enter into wildlife-use agreements, or “elk rents”

- 3. Offer priority or transferable hunting tags to landowners who provide wildlife habitat

- 4. Develop new funding sources to support wildlife conservation on working lands

- 5. Increase the amount of private lands available for public access through negotiation

Research and Technical Assistance

- 1. Engage MSU Extension, FWP, and others in generating applied research, citizen science, and best practices that help landowners live with wildlife

- 2. Integrate landowners’ knowledge or citizen science into research and data

- 3. Provide regulatory and management flexibility

Click here to read the full report and recommendations.

Introduction

The history of Paradise Valley is one of movement. Located in Southwest Montana, Paradise Valley has long been a passageway not just for wildlife, but for Native Americans, trappers, hunters, and explorers. The first government-sponsored surveys of Yellowstone passed through the valley, as have subsequent generations of visitors to Yellowstone National Park. But the original travelers were wildlife, etching out ancient pathways between high alpine plateaus and the lush lower terrain along the Yellowstone River, called Elk River by the Crow Tribe because it was a migratory route.

The movement of wildlife in this region ebbs and flows with the seasons. Today, across public and private lands, seasonal migrations are the key to healthy elk herds, and scientists are learning that private landowners are increasingly the key to healthy migrations. According to research by ecologist Arthur Middleton, some elk herds can spend up to 80 percent of their time in winter on private lands, where the snows are not so deep, forage is more attainable, and conditions are more clement. In recent years, the growing interest in the ecology and conservation of migration ungulates including elk, mule deer, and pronghorn has captured the attention of policymakers, scientists, sportsmen, and conservation organizations alike, moving the issue to the forefront of conservation priorities in the American West. In Montana, Paradise Valley is ground zero.

Paradise Valley also has a rich history of cattle ranching. It started when an enterprising miner named Nelson Story sold his gold dust from the diggings in Adler Gulch for $40,000 in post-Civil War greenbacks and headed to Texas, where he purchased a herd of 1,000 longhorn cattle. In 1866, along with 24 cowboys and 15 wagons, Story drove the herd along the new Bozeman Trail to grazing grounds in the Montana Territory, fighting Sioux war parties on the way. The 2,100-mile cattle drive was the first to Montana. Three hundred cattle were sent on to the goldfields of Virginia City while the remaining 700 wintered in Paradise Valley. The drive was the inspiration for Larry McMurtry’s classic western novel Lonesome Dove. Story would continue to use the Upper Yellowstone River valley as grazing land. His descendants still ranch in the valley today.

Today, this history is the backdrop for the recent science and conservation efforts involving wildlife migration corridors in Montana. GPS collars have enabled researchers to understand elk movements from summer to winter range in much greater detail than ever before. To date, the mapping of elk GPS data shows at least nine distinct migratory herds in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. Paradise Valley and its ranching community provide critical winter range habitat for two of those herds: the Paradise Valley Herd and the Northern Yellowstone Herd. As a result, the valley has been identified by the Montana Department of Fish, Wildlife, and Parks as one of the state’s four priority migration areas. Paradise Valley is also recognized by the state as a priority area for its other iconic migratory species, such as pronghorn and mule deer, as well as its connectivity to Yellowstone National Park.

The new, spaghetti-like migration maps for the Yellowstone elk herds and other migratory ungulates are an incredible resource for scientists, government agencies, and conservationists. But for ranchers, they too often cause additional anxiety and concern. Lines on a map often precede efforts to create official wildlife corridor designations, which can mean more regulation, oversight, and litigation for already-strained working landowners, most of whom are excellent stewards of wildlife. Unfortunately, landowners often feel as though they are the last to learn of these efforts.

In truth, elk can be hard on cattle ranchers. When the snow flies in the high country, the herds move down to lower-elevation pastures. On these ranches, the elk compete with cows for winter hay and irrigated alfalfa. They damage fences. They attract predators. And they can spread brucellosis, a disease carried by elk in the Yellowstone region that causes cattle to abort their unborn calves. It is brucellosis that keeps the Paradise Valley ranchers awake at night. The stress and costs take their toll, and many landowners say that their tolerance for elk is wearing thin. Since the mid-1990s, ranchers have reported seeing more and more elk on their agricultural fields, and they are staying longer. Many wonder if migratory elk aren’t becoming residential elk, content to feed upon the valley’s irrigated lowlands year-round.

In 2019, the Property and Environment Research Center (PERC) embarked on a multi-year effort to better understand landowners’ attitudes and challenges with wildlife in Paradise Valley. In addition to conducting an extensive landowner survey, PERC hosted a one-day landowner workshop at Chico Hot Springs in Pray, Montana, which brought together nearly 40 members of Paradise Valley’s ranching community. The workshop provided an opportunity for ranchers to discuss the survey results and possible economic and other incentives that could help them with their challenges of coexisting with elk. Ranchers also had the opportunity to interact with leading officials from Montana Fish, Wildlife, and Parks and the U.S. Department of the Interior as well as some of the nation’s top researchers on elk migrations and private lands, including Arthur Middleton.

This report is a summation of the survey results, the workshop, and the many hours spent in conversations with working landowners in their kitchens or at local saloons. It puts forth a toolkit of ideas to support landowners, recognizing that if we help the landowners—if we find ways to economically preserve working lands—we help the wildlife. Recommendations focus on private landowner recognition and appreciation, research, technical and regulatory relief assistance, and economic incentives.

We are indebted to the ranchers and landowners of Paradise Valley who shared their time, experience, and opinions with us. This report would not be possible without them. We are especially indebted to Druska Kinkie, who was instrumental in opening doors and helping us better understand and appreciate the ranching community in Paradise Valley.

The goal of the project is to explore market-based approaches, economic tools, and other ways that can enable elk migrations to become more of an asset, or at least less of a liability, to private landowners, thereby preserving the working landscape nature of Paradise Valley and the habitat that migratory elk rely on. After all, wildlife are an important economic driver in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, helping to generate enormous benefits from tourism and hunting opportunities around Yellowstone National Park—benefits that often do not accrue to the valley’s working landowners who supply important habitat. And, in such a highly desirable region, the likely alternative to these private working lands is fragmentation and development, which would jeopardize the future of the valley’s rural character, agricultural tradition, and the wildlife populations it supports. But it is not too late. There are those who value the conservation of wildlife migrations, and there are those who bear the costs of wildlife migrations. In between the two groups are solutions.

— Brian Yablonski, CEO, PERC