Prepared statement before the U.S. Senate Committee on Environment and Public Works’s hearing on “Stopping the Spread: Examining the Increased Risk of Zoonotic Disease from Illegal Wildlife Trafficking.”

Main Points

- Zoonotic disease spillover and the potential for pandemic is a national security threat to the United States.

- Conserving intact wildlands in regions like Africa is essential to preventing such spillover and discouraging the wildlife trafficking that amplifies the risk.

- Chinese companies and consumers remain key players in the degradation of African wildlands and trafficking of African wildlife.

- Longstanding efforts of the Chinese government to decrease involvement of their citizens in these harmful activities have not met with desired levels of effectiveness at the necessary speed.

- The United States must assume a greater leadership role in discouraging the degradation of African wildlands and trafficking of African wildlife. These efforts should ensure that concern for the ability of African partners to conserve ecosystems and field anti-poaching programs are incorporated in Endangered Species Act decision making and be careful to avoid overreach, such as through blanket bans on the trade and consumption of wildlife.

Introduction

In 2019, the Worldwide Threat Assessment by the U.S. Director of National Intelligence identified pandemic disease as one of the preeminent threats to the security of the United States. The same assessment also identified the illegal trafficking of natural resources by transnational criminal organizations and the degradation of ecosystems as contributing factors to this threat, as well as threats in-and-of themselves.[1]

The accuracy of this warning is embodied in the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic, which has claimed 136,938 American lives, made 3.5 million sick,[2] and which the Congressional Budget Office projects will cost our economy upwards of $7.9 trillion over the next decade.[3] While the exact origins of the pandemic are still unknown, U.S. intelligence agencies have expressed a high degree of confidence that those origins are natural,[4] an assessment[5] supported by published, peer-reviewed literature strongly suggesting a genesis in wildlife.[6]

The global tragedy we are witnessing highlights how permeable the line is between our civilization and those parts of the world we deem wild. It also draws into clear focus the inseparability of ecological sustainability and national security. Wildlife-borne pathogens capable of incapacitating millions and shutting down the global economy have shown themselves to already be inside our door. Scientists warn that diseases capable of more far reaching destruction, a “Disease,” may await us [7] in the planet’s remaining wildlands,[8] areas our civilization has increasing contact with via the pathways created by unsustainable development [9] and the trafficking of wildlife.[10]

Our collective environmental stewardship will determine whether or not the scale of the threat we face from zoonotic disease increases or diminishes. Conserving intact and healthy ecosystems and increasing efforts to curtail wildlife trafficking are key to achieving this goal and should be given increased priority in U.S. foreign policy.

Our country’s conservation partnerships in Africa will be key to achieving success. The potential for another pandemic to arise as a result of deforestation, other types of land clearing, or wildlife trafficked out of the continent’s wildlands is high. At the same time the opportunity costs for allowing and participating in these activities remain low due to persistent poverty and a lack of individual and community investment in conservation outcomes. These economic and political conditions have encouraged natural resource extraction projects, often backed by Chinese investment [11], that in many cases are unsustainable, and in some cases, criminal.[12] Despite efforts of the Chinese government to encourage environmentally responsible behavior, Chinese companies and consumers remain key players in both the degradation of African ecosystems and the trafficking of African wildlife. Given the overlap of unsustainable development and source markets for wildlife products with known hotspots and correlates of emerging zoonotic diseases they should be viewed as key propagators of disease risk.

For this reason, the United States should commit to assuming a greater leadership role in supporting efforts to conserve intact wildlands in Africa and maintain or increase the opportunity costs for involvement in poaching. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service can play a key role in this endeavor by taking into account the unintended consequences of decisions made under the Endangered Species Act. Considering the impact of listing and importation decisions on the ability of African nations to conserve habitat and field anti-poaching programs would firmly integrate Endangered Species Act enforcement into a “one health” approach, uniting our efforts to protect the environment and prevent future pandemics. Educating U.S. consumers about the environmental and public health costs of products made from African hardwoods manufactured in China can help reduce threats to the Congo Basin, a region whose future is key to our health security.

Finally, while the scale of the threat we face is significant, we must be careful not to overreach with blanket bans on the use of wildlife or by discouraging aspects of wildlife trade that produce great benefits for conservation and public health while generating little risk of disease spillover or transmission. Such overreach is likely to be met with disappointing results and could in fact make the risk of viral spillover greater and disease outbreaks harder to investigate.

The Threat Posed by Zoonotic Disease

In 2018, the World Health Organization began including “Disease X” in its R&D Blueprint for Action to Prevent Pandemics. “Disease X” represents a hypothetical pathogen that could cause a future epidemic or pandemic.[13] Current research suggests that 75 percent of emerging diseases are zoonotic in nature, meaning they originate in animals,[14] and that 60 percent of diseases known to currently occur within the human population are transmitted by animals.[15] For this reason, there is a high degree of probability that Disease X is zoonotic.

Covid-19 fits the description of Disease X, but it is unlikely to be a threat without peer.[16] The number of viruses on our planet is estimated to be more than 10 nonnillion (1031).[17] Mammals, especially bats, rodents, primates, and pangolins are believed to present some of the most significant risk to humans as reservoirs of disease.[18] The number of viruses found in mammals is unknown, but estimated to be more than 1 million, with possibly half of those posing a threat to human health.[19] Some estimate there are more than 300,000 viruses in mammals still awaiting discovery by science.[20] The takeaway is that while the exact scale of the threat of zoonotic viral spillover, the transmission of a pathogen from animal to human, may be unknown, it is likely to be large, and, as the experience of the Covid-19 pandemic illustrates, real.

Such spillovers typically occur along one of the following pathways.[21]

- Human behavior that leads to contact with the animal and the pathogen it is carrying (Excretion)

- Butchering, preparation, and eating of an infected animal (Slaughter)

- Being bitten by an infected animal (Vector borne)

Excretion is the gateway path as the other spillover pathways all involve people coming into contact with an infected animal, its parts, or its waste.

Examples of vector borne transmission include incidents of simian foamy virus, a relative of HIV, in individuals in Cameroon following severe gorilla bites [22] or a hypothetical future outbreak of Marburg virus, a type of hemorrhagic fever, stemming from a bat bite.[23] For perspective, in Ghana, 66 percent of rural residents surveyed reported being bitten by bats.[24]

Slaughter-based transmission can occur via the informal collection and trade in wild game, also called “bushmeat,” and in the commercial sale of the same at so-called “wet markets.” One example of this kind of transmission is the 2007 Ebola outbreak in the Occidental Kasai Province in the Democratic Republic of Congo. This outbreak followed the consumption of migrating fruit bats by rural people.[25] Another example is incidences of Simian T-Lymphotropic Virus Type 1 strains, which can induce adult T-cell leukemia or lymphoma, in rural Cote d’Ivoire where the consumption of primates is common.[26]

The potential of viral spillover and pandemic to threaten our national security should not be underestimated. The Spanish Flu Pandemic of 1918 killed more Americans than all of the conflicts of the 20th Century combined. Such mortality levels, in addition to related morbidity, is the primary way disease represents a security threat. Widespread death and illness have strong potential to strain America’s healthcare system and economic productivity which can help drive political instability and class strife. Pandemic disease can also impair the readiness of our military and destabilize regions of key political and economic importance to the United States [27].

Maintaining Healthy, Intact Ecosystems: The First Line of Defense

Environmental disturbances, such as road building and land clearing can increase the likelihood of viral spillover occurring because they increase opportunities for human contact with wildlife serving as disease reservoirs.[28] Such disturbances can help expand the distance bushmeat hunters and poachers are able to travel into remote areas, increasing the chance of contact with and eventual consumption or trafficking of disease-carrying wildlife.[29] These disturbances also have the potential to increase the density of high-risk wildlife, such as bats.[30] For example, recent outbreaks of Ebola Virus in Central and West Africa have shown a strong correlation with deforestation events.[31]

The infrastructure and equipment associated with such disturbances also increases opportunity for wildlife and wildlife products potentially carrying disease to be transported, legally or illegally, from local areas to urban and international markets, thereby increasing the potential for disease outbreaks that are severe in scale.[32] For example, in Cameroon, personnel and trucks associated with logging operations have been documented collecting and transporting bushmeat to markets in Bertoua, Yaounde, and Douala, cities and towns with a combined population of 5.6 million people.[33]

For these reasons, limiting environmental disturbances and keeping remote areas intact via conservation efforts should be viewed as our first line of defense in efforts to decrease the potential of any future spillover of a Disease X that can lead to pandemic.[34] Doing so will limit opportunities for contact with disease carrying wildlife in the first place and for high-risk wildlife to be trafficked across scales. In course, it will help accomplish the stated objective of the US National Security Strategy to “contain biothreats at their source.” [35]

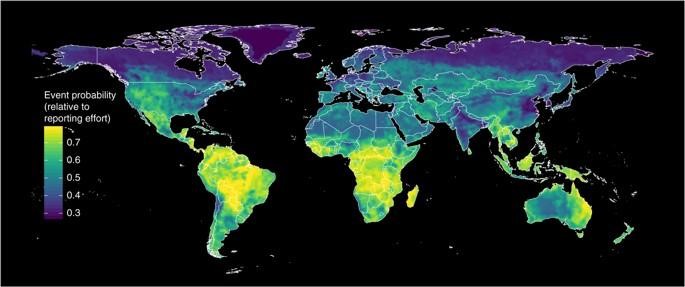

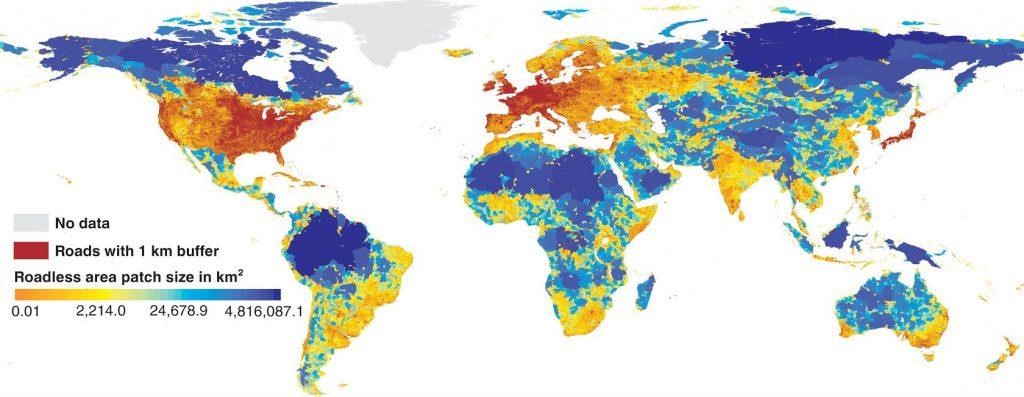

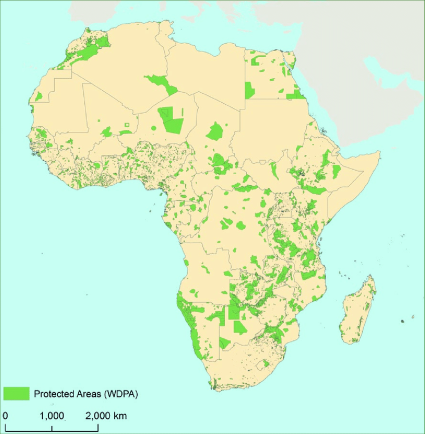

In Sub-Saharan Africa, there is significant overlap between global hotspots and correlates of emerging zoonotic diseases (Fig 1) [36] and intact ecosystems. (Fig 2).[37] There is significantly less overlap between these areas in Africa and designated protected areas where disturbance is legally controlled or restricted (Fig 3). Supporting African nations in decreasing the vulnerability of areas likely to harbor disease carrying wildlife to clearing must be given significantly increased attention in U.S. policies and programs.

Fig 1[38]

Global Hotspots and Correlates of Emerging Zoonotic Diseases

Fig 2[39].

Locations of Remaining Large, Unroaded Areas

Fig 3[40]

Designated Protected Areas in Africa

Chinese Companies Are a Key Player in the Degradation of African Ecosystems

More than 3 million hectares of forests and other natural habitats in Africa are converted each year. Agriculture and the extraction of timber are primary drivers of this conversion.[41] Increased Chinese investment in Africa’s forestry sector, coupled with Chinese consumer demand, as well as consumer demand in the United States, have been influential in encouraging this habitat loss and related risk of disease spillover.

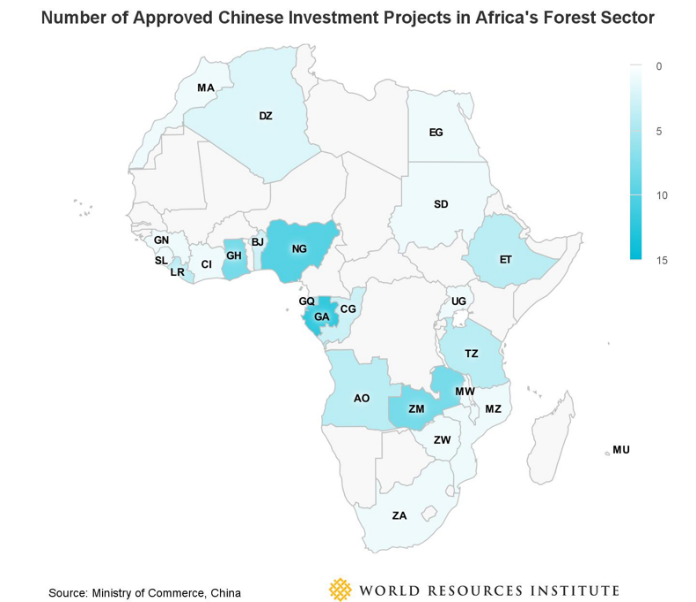

China’s Belt and Road Initiative, a government backed, transnational policy and infrastructure project intended to facilitate Chinese global expansion has helped open the door to increased Chinese investment in African forests.[42] Chinese investment in African timber projects now spans at least 24 countries (Fig 4).[43] Most of this investment is via small and medium-sized Chinese owned enterprises with no direct ties to the Chinese state.[44] Chinese investment in Africa’s forest sector is heavily weighted towards timber extraction and supplying the Chinese market for raw logs of tropical hardwoods, which is the largest in the world.[45] By some estimates, 75 percent of African timber harvested is now exported to China.[46] African forests gained increased importance as a source of wood supply after China banned all commercial logging in its natural forests in 2017.[47]

While the Chinese government has issued voluntary guidelines to encourage environmental safeguards in overseas investment,[48] the lack of official ties between the small and medium-sized enterprises in the forestry sector and Beijing, or with Chinese commercial banks, has made accountability to encourage compliance a continuing challenge. This challenge of accountability is exacerbated by relatively weak civil society combined with state control of the media in both China and some African nations.[49] These factors have fostered an environment where it has been easier for Chinese companies and their employees to worsen deforestation and be complicit in criminal activity.

Involvement of Chinese companies in deforestation is illustrated in the countries of the Congo Basin,[50] which contain a history and a high probability of future zoonotic disease spillover.[51] They also are home to a high density of intact forest ecosystems[52]and Chinese timber investment.[53] Three of the countries in the region, – Equatorial Guinea, Cameroon, and Gabon – are among the top five exporters of timber to the Chinese market.[54] Between 2001 and 2015, the export of wood from Congo Basin countries to China doubled, with 50 percent of the exports coming from Cameroon and Republic of Congo.[55] Recent research has shown that the number of logging roads in the Congo Basin has doubled since 2003 within formal logging concessions and increased by more than 40 percent outside of those concessions along with marked increases in deforestation.

Fig 4[56]

The researchers note that this expansion may increase the vulnerability of wildlife hunted for bushmeat and is concerning for the overall integrity of forest ecosystems.[57]

Deforestation in the Congo Basin has been linked to corruption and criminal activity. A 2019 inquiry by the Environmental Investigation Agency found that that the Dejia Group, a Chinese company operating in Gabon and the Republic of Congo, was linked to bribery, tax evasion, and corruption that led to rigged timber allocations, overharvesting, and the harvesting of protected species.[58]

China is the world’s largest consumer of illegal timber[59] and as noted in the 2020 World Wildlife Crime Report released by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime earlier this month, Chinese imports of African tropical timber have steadily increased over the past decade, “with a portion of this share suspected to have been illegally sourced or exported.” [60] Seizure data from the United Nations World Wildlife Seizure Database indicated that China, along with Vietnam, have been primary destinations for trafficked tropical timber, with three-fourths of all logs seized destined for one of the two countries.[61]

In Gabon, where Chinese companies comprise the largest segment of the timber industry and manage 25 percent of the country’s forest area,[62] 30,000 m3 of logs were exported to China between 2014 and 2018, despite Gabon’s ban on raw log exports.[63] A high profile example of this flouting of Gabonese law occurred in 2019, when 392 shipping containers of kevazingo wood, which is generally illegal to harvest in Gabon, were found at depots belonging to Chinese companies at the port of Owendo. Those containers then disappeared from the custody of the Gabonese Department of Justice. The ensuing scandal resulted in the eventual sacking of Gabon’s vice-president and forests minister.[64]

It is important to note that while Chinese companies are wholly responsible for their unsustainable practices and involvement in corruption, and criminal activity, U.S. consumers also play a role in driving the loss of healthy and intact forest ecosystems in Africa. The same study that identified increases in the amount of wood being exported from the Congo Basin to China also found that a significant share of this wood was ultimately turned into value added products, like furniture, to meet U.S. demand.[65] More specifically, the Environmental Investigation Agency’s expose of the Dejia Group’s activities revealed them to be a major supplier of tropical timber to US markets and contaminator of the US wood products supply chain.[66]

Stopping the Spread by Combating Wildlife Trafficking

Because they require a potentially diseased animal being removed from their natural habitat, incidents of wildlife trafficking represent a potential failure to contain biothreats at their source.

Wildlife trafficking, especially for species such as pangolins and birds, amplifies the risk of viral spillover and pandemic as a result of disease carrying wildlife being handled by multiple people across multiple countries.[67] The poor sanitary conditions under which wildlife are often trafficked increases the risk of disease spread and the criminal nature of trafficked wildlife means it bypasses veterinary and health inspections required of legal wildlife trade.[68]

Because of the relationships between wildlife trafficking, pandemic disease, and transnational organized crime it has been recognized as a national security threat since 2013 and the signing of Executive Order 13648.[69] The US commitment to responding to this threat has been further enshrined in the National Strategy for Combating Wildlife Trafficking,[70] legislation such as the Eliminate, Neutralize, and Disrupt Wildlife Trafficking Act,[71] and in programs spanning the Department of Interior[72] and US Fish and Wildlife Service,[73], Department of Homeland Security,[74] USAID[75], as well as Departments of State,[76] and Defense.[77]

Chinese Criminals Continue to Supply Chinese Consumers with Illicit Wildlife Products

Wildlife trafficking is a global challenge with involvement from actors in nearly every country.[78] Increased regional connectivity, such as through China’s Belt and Road Initiative, has led to growing concern[79] among conservationists that linkages created by this initiative and others may create new pathways that can be exploited by wildlife traffickers[80] unless mitigated by policy and practice. While the Chinese government has adopted well publicized policies, and hosted public forums for their expatriate nationals[81] with the intent of curtailing Chinese involvement in wildlife trafficking, applauded African nations’ arrest and prosecution of Chinese nationals involved in wildlife trafficking[82] and enacted penalties of between 5 and 10 years in prison for wildlife trafficking offenses,[83]achieving the desired level of success remains an ongoing process.

China has historically been a leading consumer market for wildlife products, including those sourced and imported illegally. This includes products such as elephant ivory, a traditional status symbol, as well as rhino horn and pangolins used in traditional Chinese medicine. China’s efforts to curtail illicit trade in wildlife goes back to 1993 when it banned the trade in rhino horn.[84] In response to international pressure stemming from an African elephant poaching crisis that began in 2008,[85] the Chinese government banned the purchasing and selling of ivory in the country in 2017.[86] Following the outbreak of Covid-19 in the city Wuhan, a ban was also enacted on the consumption of pangolin meat and use of pangolin scales for medicinal purposes.[87]

Recent analysis and events however show that laws are easier to change than behavior. While domestic consumption of ivory has stabilized in China, a recent report from the World Wildlife Fund found that for those Chinese who can afford to travel abroad, consumption of ivory increased 10 percent between 2018 and 2019.[88] The 2020 World Wildlife Crime Report issued by the United Nations stated that China remains a leading destination market for seized rhino horns and that Chinese nationals comprise the single largest known group of individuals arrested for rhino horn trafficking. Seizure data also reveals that China is the leading destination for pangolin shipments.[89]

As with deforestation, Chinese involvement in the trafficking of wildlife from Africa often takes the form of individuals involved in the more than 10,000 [90]small and medium sized Chinese enterprises across the continent not controlled by the Chinese state. In Gabon individuals involved in these enterprises have been identified as middlemen in the trafficking of pangolins.[91] Highly publicized criminal cases such as that of Yang Feng in Tanzania, who in addition to being a restaurateur served as Vice-President of the China-Africa Business Council, [92] have brought into sharper focus the role of some of these businesses as fronts for wildlife trafficking operations.[93]

Conclusion

Past efforts to curtail illicit wildlife trafficking and its related health and security risks have relied heavily on the actions of the Chinese government and on ending Chinese consumer demand for wildlife products. These efforts reach back more than 25 years. While the Chinese government has taken notable steps to advance the global interest in ensuring that trade in wildlife is legal and safe, the recent United Nations World Wildlife Crime Report makes clear that these efforts have not been sufficient or proceeded at the pace required. This is especially true in regard to the trafficking of pangolins which present a high risk of viral spillover and possible pandemic. The United States, through the programs of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and other agencies, must take an increased leadership role in efforts to secure global health by conserving ecosystems and curtailing wildlife trafficking, especially in and from Africa.

Recommendations

1. Support Wildland Conservation in Africa Via the Endangered Species Act

Species listing and import permitting decisions under the Endangered Species Act could produce wider benefits for conservation and health security if they were required to assess their impact on the ability of African nations to conserve intact ecosystems. Currently, these decisions can create significant financial instability in Africa’s safari hunting industry by creating barriers and obstacles to the importation of hunting trophies into the U.S. and discouraging U.S. citizens from hunting in Africa. This can adversely impact ecosystem conservation by removing the economic incentives that make this conservation possible.

More than 20 African nations currently allow the safari hunting industry to operate within their borders. Public, communal, and private hunting areas in Sub-Saharan Africa are estimated to conserve approximately 344 million acres of wildlife habitat, an area more than four times the size of the US national park system.[94]

The economic incentives to conserve habitat at this scale take various forms including revenue-sharing agreements with rural communities and direct payments to private landowners. For example, in Zimbabwe, under the Communal Areas Management Program for Indigenous Resources (CAMPFIRE), rural communities lease hunting and other tourism rights to commercial outfitters. The communities are then paid 50 percent of the revenues generated by the tourism activity.

This arrangement has incentivized the conservation of 12 million acres of wildlife habitat in Zimbabwe. Safari hunting accounts for 90 percent of the revenues raised, which totaled approximately $11.4 million between 2010 and 2015. Elephant hunting provides 65 percent of these revenues, with 53 percent of those coming from American hunters.[95]

In South Africa, where almost all of the land is in private ownership, access to the US hunting market has created incentives for farmers and ranchers to convert agricultural lands back into wildlife habitat. At present, approximately 50 million acres of private ranchlands in South Africa are being primarily managed for wildlife and ecosystem health.

It has been argued that these incentives and revenues could be replaced with photo-tourism, but the available research shows that while the two industries are mutually supportive, they are rarely interchangeable. Analysis conducted in Botswana concluded that hunting was the only economically viable wildlife-dependent land use on two-thirds of the country’s wildlife estate.[96] Other researchers have concluded that only 22 percent of the country’s Northern Conservation Zone has intermediate to high potential for photo-tourism.[97]

A 2016 study published in Conservation Biology also determined that if hunting were removed from the uses available to wildlife conservancies in Namibia, 84 percent of them would become financially insolvent. This insolvency would place an area of habitat five times the size of Yosemite National Park at risk. The same study also found that if photo-tourism was removed as a revenue stream, only 59 percent of wildlife conservancies would remain economically viable.[98]

Researchers with the University of Pretoria have determined that if just lion hunting were to end in the nations of Mozambique, Tanzania, and Zambia 15 million acres of wildlife habitat managed as hunting blocks would see decreased economic viability as wildlife habitat and increased vulnerability to land clearing.[99] More recent research conducted in South Africa found that 63 percent of the country’s private wildlife conservancies could be at increased risk due to increased restrictions on the trade in African hunting trophies.[100]

Taking these kinds of considerations into Endangered Species Act decision making will allow for it to be an asset in efforts to secure global health rather than a potential liability.

2. Educate US Consumers About the Environmental and Public Health Costs of Products Made from African Hardwoods

Conservation of healthy, intact ecosystems in places like the Congo Basin depends on reduced US demand for tropical wood products manufactured in China. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service should engage in a public educational campaign informing U.S. consumers about the costs of tropical wood products from China to African wildlife and health security. Such a campaign could be modeled on previous awareness raising efforts, such as for illegal ivory.

3. Support African Anti-Poaching Efforts via the Endangered Species Act

Wildlife trafficking begins with poaching, the illegal, uncontrolled, and unmonitored killing or capturing of wildlife. Species listing and import permitting decisions under the Endangered Species Act could produce wider benefits for conservation and health security if they were required to assess their impact on the ability of African nations to support anti-poaching programs.

Like ecosystem conservation, anti-poaching programs in Africa can be heavily reliant on the safari hunting industry which is at risk of destabilization by Endangered Species Act decisions that result in obstacles and barriers to the importation of hunting trophies into the U.S. and discourage U.S. citizens from hunting in Africa. For example, historically all of the anti-poaching activities conducted by the Tanzania Wildlife Management Authority have been funded by revenues gained via safari hunting licenses and fees. Similarly the Zimbabwe Parks and Wildlife Management Authority, the country’s primary wildlife law enforcement authority, generates 30 percent of its total operating revenue from safari hunting licenses and fees.[101] These national law enforcement authorities also often benefit from anti-poaching patrols funded by safari hunting operators that act as a force multiplier.[102]

Considering the potential impact of Endangered Species Act decisions on the ability of African nations to financially support anti-poaching programs can help ensure that key gaps in wildlife law enforcement do not develop, that poaching is discouraged, and that trafficked wildlife is interdicted as close to the source as possible, thereby decreasing the risk of it spreading disease.

4. Don’t Overreach

It is important that policy and program responses seeking to reduce the risk of viral spillover and pandemic not overreach. For example, calls for blanket bans on wildlife trade and the consumption of wildlife, as through so called wet markets” are likely to see little success, may increase the risk of viral spillover, and frustrate future efforts to track any outbreaks.

In Central Africa alone it is estimated that > 1 billion kg of wild game meat[103] from an estimated 579 million animals[104] is consumed each year. This consumption is as much a factor of necessity as it is culture. Past bans on bushmeat consumption following outbreaks of Ebola[105] only served to drive trade and consumption underground. A similar experience was had in China following the outbreak of Covid-19. [106] Increased informality and decreased visibility of markets risks degrading sanitary conditions and increasing the likelihood of zoonotic disease outbreak along with the involvement of criminal elements. This would likely frustrate efforts to investigate disease outbreaks should they occur. The creation of black markets and related rise in prices may also increase incentives for poaching.

Similarly, suggestions that banning or further restricting the importation of African hunting trophies would serve public health are unfounded and would have unintended, negative consequences. Hunting trophies already are subject to rigorous customs regulations that help ensure they are safe for importation and there has never been a documented case of a hunting trophy of an African game species being the source of a disease outbreak in the United States. As per the discussion of my other recommendations, such bans would only likely lead to decreased capacity and capability in Africa to maintain healthy ecosystems and combat poaching thereby increasing risks to public health.

Citations

[1] Office of the Director of National Intelligence. January 29, 2019. Statement for the Record. Worldwide Threat Assessment of the US Intelligence Community. Daniel R. Coats. Director of National Intelligence. Senate Select Committee on Intelligence.

[2] US Centers for Disease Control. 2020. Coronavirus Disease 2019. Cases and deaths in the US. Accessed July 17, 2020 at https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/cases-updates/us-cases-deaths.html

[3] Ziv, S. June 2, 2020. Coronavirus Pandemic Will Cost IS Economy $8 Trillion. Forbes

[4] Office of the Director of National Intelligence. April 30, 2020. Intelligence Community Statement on the Origins of Covid-19. ODNI News Release No. 11-20.

[5] Calisher, C., et. al. 2020. Statement in Support of the Scientists, Public Health Professionals, and Medical Professionals of China Combatting Covid-19. The Lancet. 395 e42-e43.

[6] Lau, S.K.P., Hayes, K.H., Antonio, C.P., Kenneth, S.M.L., Longchao, Z., Zirong, H., Fung, J., Tony, T.Y.C., Kitty, S.C.F., and C.Y.W. Patrick. July 2020. Possible Bat Origin of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus-2. Emerging Infectious Diseases Journal. 26 (7). US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Atlanta, GA.

[7] World Health Organization. 2018 Annual Review of Disease Prioritized Under the Research and Development Blueprint. Informal Consultation. 6-7 February. Geneva, Switzerland. Meeting Report.

[8] Vidal, J. March 18, 2020. Destroyed Habitat Creates the Perfect Conditions for Coronavirus to Emerge: Covid-19 May be Just the Beginning of Mass Pandemics. Scientific American. Ensia.

[9] Faust, C., et. al. 2018. Pathogen Spillover During Land Conversion. Ecology Letters.

[10] T. Wyatt. Autumn 2013. The Security Implications of the Illegal Wildlife Trade. CRIMSOC: The Journal of Social Criminology. Green Criminology Issue.

[11] Aryani, R., Ebrahim, N., and X. Weng. 2016. Chinese Investment in Africa’s Forests – Scale, Trends, and Future Policies. International Institute for Environment and Development. London, UK.

[12] Anthony, R., Esterhuyse, H., and M. Burgess. 2015. Shifting Security Challenges in the China-Africa Relationship. Policy Insights 23. Foreign Policy Program. South African Institute of International Affairs. Johannesburg, South Africa.

[13] Simpson, S., Kaufmann, M.C., Glozman, V., and A. Chakrabarti. 2020. Disease X: Accelerating the Development of Medical Countermeasures for the Next Pandemic. The Lancet. 20(5).

[14] Taylor LH, Latham SM, Woolhouse ME. Risk factors for human disease emergence. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2001;356:983–9. 10.

[15] Jones KE, Patel N, Levy M, et al. Global trends in emerging infectious diseases. Nature 2008; 451:990-94

[16] Settle, J., Diaz, S., Brondizio, E., and P. Daszak. April 27, 2020. Covid-19 Stimulus Measures Must Save Lives, Protect Livelihoods, and Safeguard Nature to Reduce the Risk of Future Pandemics. Intergovernmental Panel on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. Bonn, Germany.

[17] Microbiology by the Numbers. 2011. Nature Reviews Microbiology. 9 (628).

[18] Olival, K.J., et. al. 2017. Host and Viral Traits Predict Zoonotic Spillover from Mammals. Nature. 546(7660).

[19] Carlson, C.J., Zipfel, C.M., Garnier, R., and S. Bansal. 2019. Global Estimates of Mammalian Viral Diversity Accounting for Host Sharing. Nature Ecology and Evolution. 3(7).

[20] Anthony, S.J., et. al. 2013. A Strategy to Estimate Unknown Viral Diversity in Mammals. mBio.4(5).

[21] Plowright, R.K., et. al. 2017. Pathways to Zoonotic Spillover. Nature Reviews Microbiology. 15.

[22] Betsem, E., Rua, R., Tortevoye, P., Froment, A., and A. Gessain. 2011. Frequent and Recent Acquisition of Simian Foamy Viruses Through Ape Bites in Central Africa. PLOS Pathogens. 7(10).

[23] Steffen, I., et. al. 2020. Seroreactivity Against Marburg or Related Filoviruses in West and Central Africa. 2020. Emerging Microbes and Infections. 9(1).

[24] Anti, P. et. al. 2015. Human-Bat Interactions in Rural West Africa. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 21(8).

[25] Leroy, E.M., et. al. 2009. Human Ebola Outbreak Resulting From Direct Exposure to Fruit Bats in Luebo, Democratic Republic of Congo, 2007. Vector-Borne and Zoonotic Diseases. 9(6).

[26] Calvignac-Spencer, S., et. al. 2012. Origin of Human T-Lymphotropic Virus Type 1 in Rural Cote d’Ivoire. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 18(5).

[27] Evans, J. 2010. Pandemics and National Security. Global Security Studies. 1(1).

[28] Johnson, C.K. April 8, 2020. Global Shifts in Mammalian Population Trends Reveal Key Predictors of Virus Spillover Risk. Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

[29] Bausch, DG, and L. Schwarz. 2014. Outbreak of Ebola Virus Disease in Guinea. Where Ecology Meets Economy. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 8(7).

[30] Rogalski, M.A., et. al. 2017. Human Drivers of Ecological and Evolutionary Dynamics in Emerging and Disappearing Infectious Disease Systems. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society. 372(1712).

[31] Olivero, J., et.al. 2017. Recent Loss of Closed Forests is Associated With Ebola Virus Disease Outbreaks. Scientific Reports. 7.

[32] Nishihara, T. 2003. Elephant Poaching and Ivory Trafficking in African Tropical Forests with Special Reference to the Republic of Congo. Pachyderm. 34

[33] Usongo, L. 2003. Preliminary Results on Movements of Radio-Collared Elephant in Lobeke National Park, South East Cameroon. Pachyderm. 34.

[34] Supra 21.

[35] The White House. December 2017. National Security Strategy of the United States of America. Washington, DC.

[36] Allen, T., et. al. October 24, 2017. Global Hotspots and Correlates of Emerging Zoonotic Diseases. Nature Communications. 8 (1124).

[37] Ibisch, P.L.., Hoffman, M.T., Kreft, S. and G. Pe’er. 2016. A Global Map of Roadless Areas and their Conservation Status. Science. 354 (6318).

[38] Supra 36.

[39] Supra 37.

[40] Shennan-Farpon, Y., Burgess, N.D., and F. Danks. 2016. The State of Biodiversity in Africa: A Mid-Term Review of Progress Towards the Aichi Biodiversity Targets. UNEP-WCMC. Cambridge, UK.

[41] Supra 39.

[42] Mayers, J. June 19, 2019. China’s Investments, Africa’s Forests: From Raw Deals to Mutual Gains. International Institute for Environment and Development. London, UK.

[43] Li, B. and Yan, Y. February 11, 2016. How Does China’s Growing Overseas Investment Affect Africa’s Forests: 5 Things to Know. Global Forest Watch.

[44] Brautigam, D. April 1, 2020. Putting a Dollar Amount on Chinese Loans to Low Income Countries. China Africa Research Initiative. Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies.

[45] Global Witness. 2019. Lesson’s From China’s Global Forest Footprint: How China Can Rise to a Global Governance Challenge. London, UK.

[46] J. Mayers. June 2015. The dragon and the giraffe: China in African forests. International Institute for Environment and Development. Briefing. London, UK. Accessed July 2, 2020 at https://pubs.iied.org/pdfs/17302IIED.pdf?

[47] Global Times. March, 16, 2017. China Imposes Total Ban on Commercial Logging, Eyes Forest Reserves.

[48] People’s Republic of China, Ministry of Commerce. February 18, 2013. Notice of the Ministry of Commerce and the Ministry of Environmental Protection on Issuing the Guidelines for Environmental Protection in Foreign Investment and Cooperation. Shang He Han [2013] No. 74.

[49] Fuller, T.L., et. al. 2018. Assessing the Impact of China’s Timber Industry on Congo Basin Land Use Change. Area. Royal Geographical Society. London, UK.

[50] These include: Cameroon, Central African Republic; Democratic Republic of the Congo; Republic of the Congo; Equatorial Guinea; and, Gabon.

[51] Supra 35.

[52] Supra 36.

[53] Putzel, L. et al. 2011. Chinese trade and investment and the forests of the Congo Basin: Synthesis of scoping studies in Cameroon, Democratic Republic of Congo and Gabon. CIFOR Working Paper 67.

[54] Global Witness. April 1, 2019. Lesson’s From China’s Global Forest Footprint: How China Can Rise to a Global Governance Challenge. London, UK.

[55] Supra 48.

[56] Supra 43.

[57] Kleinschroth, F., Lporte, N., Laurance, W.F., Goetz, S.J., and J. Ghazoul. June 2019. Road Expansion and Persistence in Forests of the Congo Basin. Nature Sustainability.

[58] Environmental Investigation Agency. 2019. Toxic Trade: Forest Crime in Gabon and the Republic of Congo and Contamination of the US Market. Washington, DC.

[59] Environmental Investigation Agency. 2012. Appetite for Destruction. Report. London, UK.

[60] United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. 2020. World Wildlife Crime Report: Trafficking in Protected Species. Vienna, Austria.

Supra 58.

[62] Yoan, A.O., Xue, Y., and M.J.M. Kiki. 2018. Gabon Wood Industry and Chinese Company Activities. Open Access Library Journal. 5.

[63] Environmental Investigation Agency. 2018. African Log Bans Matter: Reforming Chinese Investment and Trade in Africa’s Forest Sector. Washington, DC.

[64] Reuters. May 22, 2019. Gabon President Fires VP, Forests Minister Over Hardwoods Scandal.

[65] Supra 48.

[66] Supra 63

[67] Huong, N.Q., et. al. 2020. Coronavirus Testing Indicates Transmission Risk Along Wildlife Supply Chains for Human Consumption in Vietnam, 2013-2014.BioRxiv.

[68] Karesh, W.B., Cook, R.A., Bennett, E.L., and Newcomb, J. 2005. Wildlife Trade and Global Disease Emergence. Emerging Infectious Diseases.

[69] 3 CFR 13648 – Executive Order 13648 of July 1, 2013. Combating Wildlife Trafficking.

[70] The White House. February 11, 2014. National Strategy for Combating Wildlife Trafficking. Washington, DC.

[71] P.L. 114-231.

[72] US Department of the Interior. Undated. Combating Wildlife Trafficking Worldwide. Factsheet. US Department of the Interior, International Technical Assistance Program. Washington, DC.

[73] US Fish and Wildlife Service. 2018. Combating Wildlife Trafficking Program, FY 2018 Summary of Projects. US Department of the Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service, Division of Management Authority. Arlington, VA.

[74] US Department of Homeland Security, Undersecretary for Management. 2018. Illegal Trafficking of Wildlife and Other Natural Resources, FY 2018 Report to Congress. Washington, DC.

[75] US Agency for International Development. 2019. Countering Wildlife Crime. Factsheet. US Agency for International Development, Environment Office, Kenya/East Africa. Nairobi, Kenya.

[76] US Department of State, Bureau of Oceans, Environment and Science. 2019. 2019 END Wildlife Trafficking Report to Congress. US Department of State, Washington, DC.

[77] Summers, E. September 23, 2016. US Soldiers Team with Tanzania Rangers to Combat Poaching. US Army.

[78] Supra 58.

[79] Hughes, A.C. 2019. Understanding and Minimizing the Environmental Impacts of the Belt and Road initiative. Conservation Biology. 33(4).

[80] Farhadinia, M.S., et. al. Belt and Road Initiative May Create new Supplies for Illegal Wildlife Trade in Large Carnivores. August 12, 2019. Nature Ecology and Evolution.

[81] Hongjie, L. march 26, 2019. China Calls on Citizens in Africa: Stop Wildlife Trafficking. China Daily.

[82] Chen, L. February 20, 2019. Beijing Backs Jail Term for Chinese Ivory Queen Yang Fenglan in Tanzania. South China Morning Post.

[83] Criminal Law of the Peoples Republic of China. Art. 341.

[84] Wudunn, S. June 6, 1993. Beijing Bans Trade in Rhino and Tiger Parts. The New York Times. Pp. 19.

[85] Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species. March 3, 2016. African Elephants Still in Decline Due to High Levels of Poaching. Press Release. Geneva, Switzerland.

[86] Agency France-Presse. December 31, 2017. China Imposes Total Ban on Elephant Ivory Sales.

[87] Westcott, B. June 10, 2020. China Removes Pangolin Scales From Traditional Medicine List, Helping Protect the World’s Most Trafficked Mammal. CNN.com.

[88] World Wildlife Fund. 2019. Demand Under the Ban: China Ivory Consumption Research 2019. Beijing, China.

[89] Supra 89.

[90] Yuan-Sun, I., Jayaram, K., and O. Kassiri. 2017. Dance of the Lions and Dragons: How are Africa and China Engaging and How Will the partnership Evolve? McKinsey and Company. Chicago, IL.

[91] Mambeya, M.M., et. al. 2018. The Emergence of Commercial Trade in Pangolins from Gabon. African Journal of Ecology. 56(3).

[92] Sieff, K. October 8, 2015. Prosecutors Say This 66-Year-Old Chinese Woman is One of Africa’s Most Notorious Smugglers. The Washington Post.

[93] Tremblay, S. April 7, 2019. Chinese “Queen of Ivory” Jailed for 15 Years in Tanzania. CNN.com

[94] PERC analysis

[95] CAMPFIRE Association. 2016. The Role of Trophy Hunting in Support of the Zimbabwe CAMPFIRE Program. CAMPFRE Association. Harare, Zimbabwe

[96] Barnes, J. 2001. Economic Returns and Allocation of Resources in the Wildlife Sector of Botswana. South African Journal of Wildlife Research. 31: 141-153

[97] Winterbach, C.W., Whitesell, C. and M.J. Somers. 2015. Wildlife Abundance and Diversity As Indicators of Tourism Potential in Northern Botswana. PLoS One. 10.

[98] Naidoo, R., Weaver, L.C., Diggle, R.W., Matongo, G., Stuart-Hill, G. and C. Thouless. 2016. Complimentary Benefits of Tourism and Hunting to Communal Conservancies in Namibia. Conservation Biology. 30:3

[99] Supra 72.

[100] Parker, K., et. al. 2020. Impacts of a Trophy Hunting Ban on Private Land Conservation in South African Biodiversity Hotspots. Conservation Science and Practice.

[101] Tendaupenyu, I.H. June 24, 2014. Statement Before the U.S. House of Representatives, Committee on Natural Resources, Subcommittee on Fisheries, Wildlife, Oceans, and Insular Affairs. Oversight Hearing on The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s Plan to Implement a Ban on the Commercial Trade in Elephant Ivory. Serial No. 113-76.

[102] Lindsey, P. 2008. Trophy Hunting in Sub-Saharan Africa: Economic Scale and Conservation Significance. In, Baldus, R., Damm, G.R., and K. Wollscheid (eds): Best Practices in Sustainable Hunting: A Guide to Best Practices Around the World. CIC Technical Series Publication 1. CIC and UN Food and Agriculture Organization. Pp. 41-47.

[103] WIlkie, DS, and JF Carpenter. 1999 Bushmeat Hunting in the Congo Basin: An Assessment of Impacts and Options for Mitigation. Biodiversity Conservation. 8.

[104] Peres, Fa JE. 2003. Game Vertebrate Extraction in African Neotropical Forests: An Intercontinental Comparison. In Reynolds, JD, Mace, GM, Redford, KH, and JG, Robinson, eds. Conservation of Exploited Species. Cambridge. Cambridge University Press. P. 203-241.

[105] Bonwitt, J., et. al. 2018. Unintended Consequences of the “Bushmeat Ban” in West Africa During the 2013-2016 Ebola Virus Disease Epidemic. Social Science and Medicine. 200.

[106] Standaert, M. march 24, 2020. Illegal Wildlife Trade Goes Online as China Shuts Down Markets. Al Jazeera.