DOWNLOAD THE FULL REPORT

Revenues from visitors have become a significant funding source for some public land sites in recent years. Visitor revenues empower local land managers by freeing them from many of the political considerations that influence congressional appropriations. As a result, they give land managers sound incentives to prioritize visitors and financial resources to create a better overall experience on public lands. When structured well, recreation fees connect visitors and their needs to the park superintendents, forest supervisors, and other local managers who serve them, aligning incentives between users and managers.

Visitors also add costs and create impacts on public lands, from staffing needs to wear and tear on trails, so it is only fair that they help cover those costs. It is also logical that the people who benefit from recreation opportunities directly support the provision of them. Recreation fees help realize both of these concepts—covering visitor costs by charging for a portion of the benefits received.

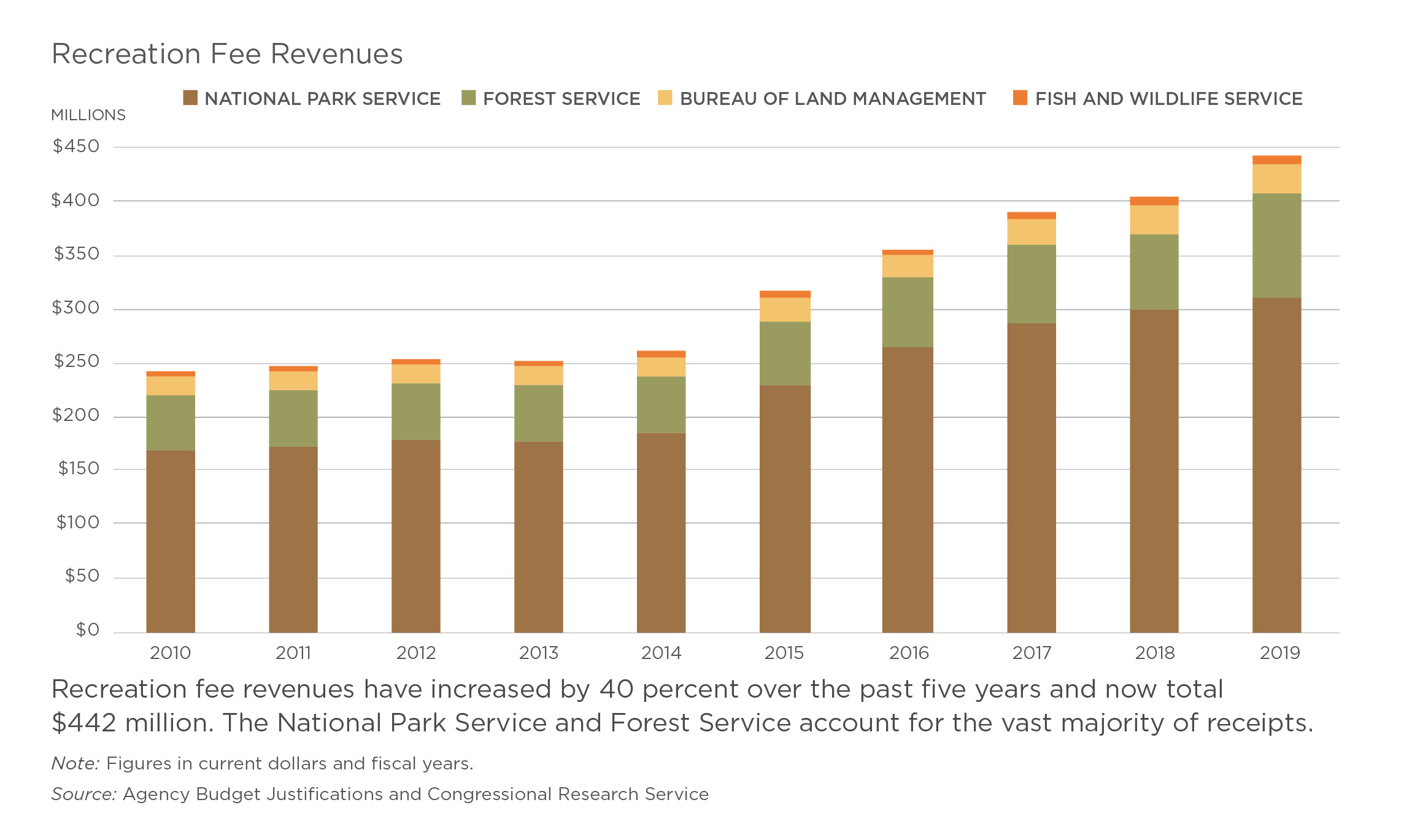

- Combined fee revenues from all federal land management agencies have risen by 40 percent over the past five years, from $316 million to $442 million.

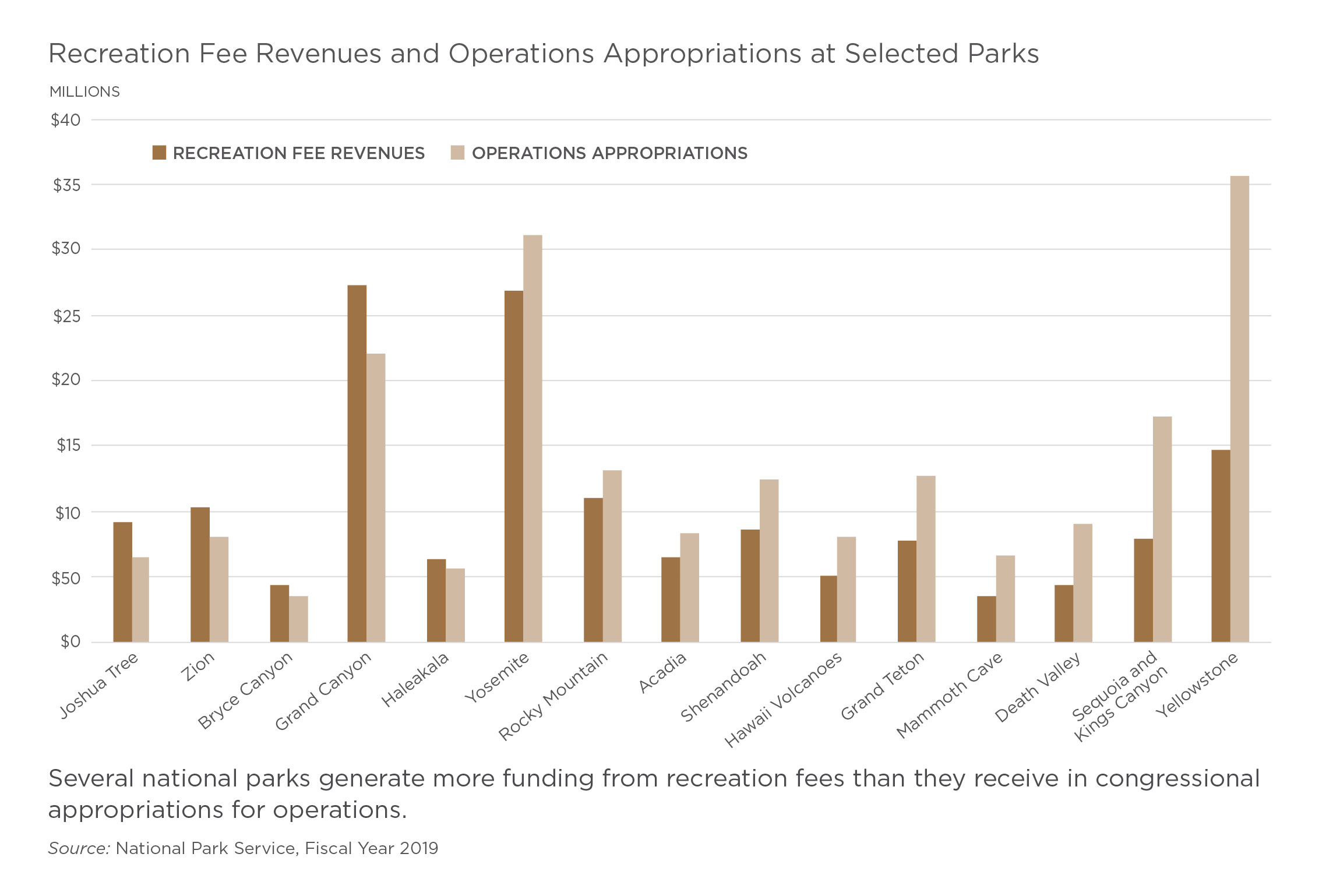

- Several national parks now generate as much revenue from visitors as they receive in discretionary funding from Congress.

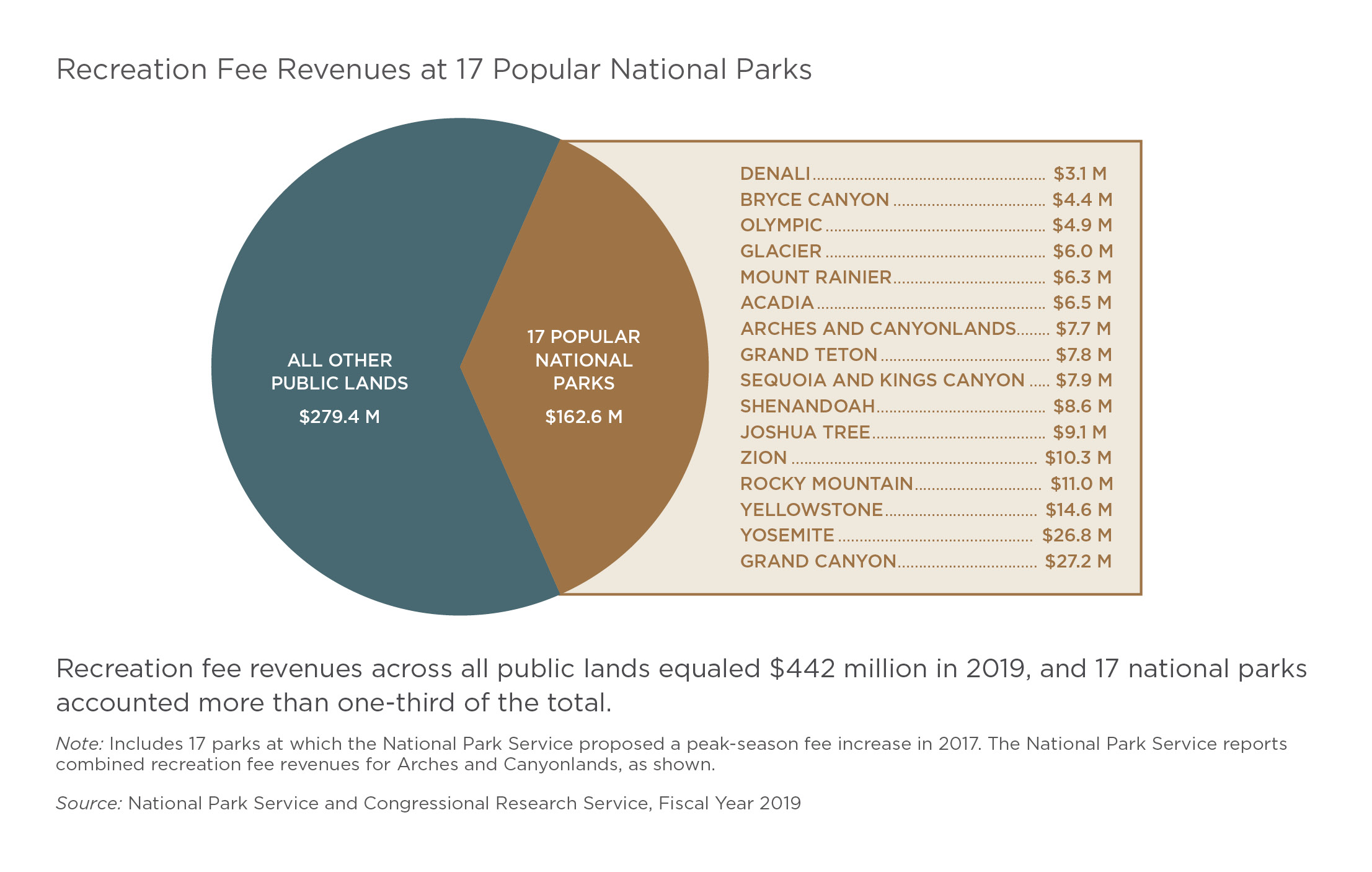

- Seventeen highly visited national parks generated $163 million in revenue last year, or more than one-third of all fee revenue across all agencies.

The current policy governing recreation fees on public lands has many merits, but legislative reform could update and improve the model so that visitors help public lands flourish even more. Likewise, changes at the agency level could promote better management of public recreation lands in the future. Ultimately, reforms could help agency managers use fee revenues to serve more visitors and enhance more recreation sites.

Recommendations:

- Reform the Federal Lands and Recreation Enhancement Act to allow all federal land agencies to charge entry fees.

- Give federal land agencies long-term fee authority by permanently authorizing the updated program.

- Grant more authority to park superintendents, forest supervisors, and other public land managers to set fees.

- Eliminate agency directives that tie the hands of local managers when it comes to spending fee revenues.

- Clarify that managers are permitted to use their fee receipts for operations and permanent visitor-service employees.

- Explore ways to implement a surcharge for overseas visitors.

- Encourage experimentation in fee structures at individual recreation sites.

- Consider raising the price of the annual recreation pass.

The Current Public Lands Fee System

Under the Federal Lands Recreation Enhancement Act, various federal sites charge recreation fees for activities like entry to a wildlife refuge or national park or rental of a campsite in a national forest. There are four broad categories of fees that can be charged under the act: entrance, standard amenity, expanded amenity, and special recreation permit. The National Park Service and Fish and Wildlife Service are the only land management agencies that can charge entrance fees. The Forest Service, Bureau of Land Management, and Bureau of Reclamation can charge standard amenity fees at sites that provide certain visitor services or facilities. All of the agencies can charge expanded amenity fees for use of campgrounds, boat launches, cabins, day-use areas, or similar facilities. All can also charge special permit fees for activities like group use or motorized recreational vehicle use. Agencies are subject to various prohibitions in the statute that govern where, how, and for whom such fees can be levied.

Fees help separate recreation from politics.

The Federal Lands Recreation Enhancement Act not only grants federal land managers the authority to charge fees, but crucially, it also permits them to retain and spend most of the receipts where they are collected. Because local managers can spend fee revenues they generate, the decision-making authority over these funds is transferred from far-away legislators to the people on the ground managing recreation sites. This empowers park superintendents, forest supervisors, and other local managers to make decisions about how to best serve visitors. It also removes a degree of political influence from spending decisions.

Federal recreation sites have been allowed to retain most of the fee revenues they generate since the 1990s. The model completes the visitor-site feedback loop and provides direct incentives for managers to enhance the experience of recreating on public lands, features missing from the previous approach. An impetus for the current fee model was the 1990s closure of a popular campground in Yellowstone National Park that brought in more than enough fee revenue to cover its operating costs; however, the park did not retain the money it generated. All of the receipts went to the U.S. Treasury, meaning that appropriators could use the funds for education, defense, or whatever other federal spending purpose they deemed fit. While land managers no doubt sought to serve visitors under the old model, they had much less reason to prioritize fee revenues or to invest in strategies to grow those revenues.

Today, each individual site generally retains 80 percent of its collections to be spent at that site without further appropriation. Agencies decide how to spend the remaining 20 percent, which usually funds projects at units or sites that do not charge fees. Local managers who serve users’ needs well and improve the visitor experience can now benefit directly if their efforts increase fee revenues. Managers also have much better knowledge about site operations and on-the-ground priorities than appropriators, so allowing them to make decisions about where to spend revenues is sensible.

Revenues from recreation fees have become a significant share of some national park budgets in recent years. This is due to a combination of increased visitation, new fees, and increases of existing fees. In total, fee revenues have risen by 40 percent over the past five years, from $316 million to $442 million. About 70 percent of all fee revenue is generated by the National Park Service, while the Forest Service generates another 22 percent of the total.

The distribution of fee revenue across sites is extremely varied. Some recreation sites charge no fees and hence have no fee revenue, while several national parks generate more revenue from fees than they receive in discretionary funding from Congress. Seventeen highly visited national parks generated $163 million in revenue last year, or more than one-third of all fee revenue across all agencies.

Yet on many federal lands, a direct charge for use remains the exception rather than the rule. About 40 percent of national park units charge a fee of some sort, and 43 percent of wildlife refuges do. Just 12 percent of BLM sites and 13 percent of the 30,000 developed Forest Service sites charge for amenity use. Across the approximately 35,000 developed recreation sites administered by the four major land management agencies, recreation fees are charged at less than 15 percent of sites.

Entry fees are modest compared to alternatives. At premier U.S. national parks, entry fees are at most $35 per week per private vehicle. A family of four might pay that much for a visit to a public pool or trip to the movie theater. In other countries that charge for admission to national parks, fees are often higher. Likewise, objections that admission fees will “price people out” of public lands are largely overstated. Even at the top-tier national parks with the highest entry fees of any U.S. public lands, the price of admission is usually a small portion of overall travel expenses. For instance, past visitor surveys at Yellowstone and Yosemite have found that admission fees represent roughly 3 percent of total expenditures in and around the parks.

Visitors simultaneously reap the benefits of recreation opportunities and create more costs than Americans who do not visit public lands. On average, every American contributes about a dime to Yellowstone National Park through tax dollars each year. Paying the $35 entry fee for a week-long visit therefore contributes 350 times more than the average citizen—additional revenue that is retained by the park and agency to serve visitors.

Improvements can bring even more benefits.

While the current fee system provides clear incentives to respond to visitor needs, it has limitations. One is the set of restrictions on where fees can and cannot be charged. The fact that the Forest Service and BLM cannot charge for entry to an area limits these agencies’ ability to generate revenue that could be used to benefit visitors directly. It also may encourage these agencies to set higher prices for amenities like campgrounds and cabins than they otherwise would. Modest entry fees paid by all hikers, mountain bikers, kayakers, or other visitors to a recreation area would spread the cost of visitor impacts over a wider base of users.

Visitor fees are not feasible or appropriate everywhere. At many sites, particularly many historic or remote ones, charging for entry or the use of amenities would be inappropriate, cost-prohibitive, or even counterproductive. But there are sound reasons to charge visitors more than general taxpayers who do not visit—nor impact—recreation lands. And given that discretionary appropriations for recreation purposes have largely stagnated in recent years, fee revenues also represent a way for site managers to have a say in their own funding.

Relatedly, some prohibitions on how and where fees can be charged result in strange incentives. To charge a standard amenity fee, a Forest Service or BLM site must have all of the following: developed parking, a permanent toilet, a permanent trash receptacle, a sign or exhibit, picnic tables, and security services. The way that the agencies have fulfilled these requirements at some areas has been contentious. For instance, near Sedona, Arizona, the Red Rock Pass was implemented to charge for use within certain sites and corridors of Coconino National Forest that encompassed a wide geographical area containing all of the required amenities. A legal challenge forced the agency to reduce the area and number of sites where it requires the pass.

Partly as a consequence of such rulings, agencies have installed picnic tables and other amenities at some sites where they would not be warranted by demand but where their presence allows a fee to be charged. The outcome—money spent on underused amenities—is an illogical and wasteful consequence of the legislation’s prohibitions. User groups have also argued that special use fees, such as off-road motor vehicle permit fees, amount to de facto entry fees at some sites that are prohibited from charging entry fees. Legislators had clear reasons for originally enacting such limitations on how and where fees could be charged, but in some instances implementation of fees under the act has been crude or inept, resulting in acrimony, disputes, and incoherence.

A separate but important issue is internal directives from land management agencies that can create perverse incentives for local managers. One of the most notable is the National Park Service directing parks to spend 55 percent of fee receipts on deferred maintenance. The directive was borne from valid concerns over snowballing deferred maintenance backlogs. After all, having a source of funds to address backlogs was part of the justification for making the original fee demonstration program permanent. But the directive gives superintendents reason to let routine maintenance lapse and become deferred, making such projects eligible to be addressed with fee revenues. Deferred maintenance can disrupt public access and is often more expensive and time consuming to address than routine maintenance, meaning the directive can negatively affect visitors and increase maintenance costs.

Reforms for a Modern Fee System

Various reforms could extend the benefits of the fee structure established under the Federal Lands and Recreation Enhancement Act to more public recreation lands, and permanently authorizing an updated fee program would provide local land managers with certainty about its future. Similarly, several agency actions could improve the existing system, making fees work better for visitors and managers alike and providing dedicated funding to better steward our public lands into the future.

Recommendations:

Reform the Federal Lands and Recreation Enhancement Act to allow all federal land agencies to charge entry fees.

The Forest Service, Bureau of Land Management, and Bureau of Reclamation should be allowed to charge entry fees in addition to their current amenity fee authority, while still adhering to the requirement that fees only be charged at sites with enough visitation to cover costs of collection. Extending entrance fee authority to these agencies would provide local managers more options for collecting revenue that can be used to enhance visitor services. The agencies should be permitted to charge for entry at heavily used sites with enough visitors and hence revenues to justify collection costs. This change would also better reflect the realities of recreation visitation today by eliminating the incentive for agencies to implement illogical or incoherent fee structures that stem from prohibitions on entry fees and have spurred disputes in the past. Relatedly, in cooperation with the agencies, Congress should reexamine statutory prohibitions on charging entrance fees at specific sites, especially where such fees could be implemented in a way that exempts locals.

Give federal land agencies long-term fee authority by permanently authorizing the updated program.

The Federal Lands Recreation Enhancement Act is set to expire October 1, 2021. Legislators should reform and then permanently authorize the updated legislation. Making the program permanent would give agencies more certainty about future revenue streams from visitors. If agencies can consider fee dollars to be a more secure and longer-term source of funding, then they can more readily use those funds not only for one-off projects like deferred maintenance, but also for recurring expenses, such as addressing routine maintenance before it becomes overdue.

Grant more authority to park superintendents, forest supervisors, and other public land managers to set fees.

Onerous and time-consuming processes required to adjust national park fees have discouraged units from altering fee structures in the past. At times, agency-mandated moratoriums on fee increases and the lack of a mechanism to smoothly keep fees in line with inflation have also reduced potential revenues. Managers should be able to adjust fees to better reflect value as well as the price of alternatives.

Eliminate agency directives that tie the hands of local managers when it comes to spending fee revenues.

Agency oversight will always remain crucial, but local managers have the most knowledge and best context about priorities at recreation sites. Agencies should defer to local managers on decisions about how to spend recreation fee receipts and then hold them accountable. Vesting authority at the local level allows managers to take advantage of their on-the-ground knowledge, and it can also promote accountability because it is clear who is responsible for spending decisions.

Specifically, the National Park Service should sunset its agency rule that parks spend 55 percent of fee receipts on deferred maintenance. Often routine maintenance can be just as important to address as overdue projects, and local staff are best positioned to know what type of maintenance to prioritize. While an appropriate split for maintenance spending from fee revenues may vary a great deal from park to park, the overall split has been drastic. In 2018, for instance, the National Park Service spent approximately 23 times more recreation fee revenues on deferred maintenance ($148.7 million) than routine maintenance ($6.3 million). The agency directive also can perversely encourage superintendents to allow maintenance to become deferred, possibly increasing costs and muddling asset value assessments. Lastly, the directive is less relevant now that the Great American Outdoors Act will provide dedicated funding for deferred maintenance in coming years.

Clarify that managers are permitted to use their fee receipts for operations and permanent visitor-service employees.

As long as spending falls under the types of expenditure allowed under the act, agencies should defer to local managers on use of fee receipts. A superintendent or supervisor with a recurring stream of fee revenue should be permitted to fund operations or hire employees with self-generated funds. Oversight is imperative, but agencies should trust local management to know what is needed on the ground and allow them to address those needs insofar as they can with their fee revenues. Clarifying that local managers may use fees for operations that enhance visitor enjoyment, access, or other permitted expenditures is now more important in light of the Great American Outdoors Act, which provides dedicated funding for deferred maintenance, not operations.

Explore ways to implement a surcharge for overseas visitors.

Foreign tourists who by definition have the means to pay for a trip abroad pay the same standard entry fee to public lands as a local U.S. resident on a day trip. If an American visits a national park in many other countries, however, it is often assumed that the entry fee will be higher than what locals pay. Even with an entry fee double the one charged to U.S. residents—a common degree of the upcharge in countries that use such pricing—gate fees would likely represent less than 1 percent of total trip costs for many international tourists.

Tiered pricing for international visitors could increase recreation fee revenues appreciably. In 2019, 13.6 million overseas travelers visited a national park or national monument, representing one-third of all visitors to the United States from abroad. A $10 to $20 surcharge per overseas visitor could raise $136 million to $272 million, equivalent to a 44 to 88 percent increase in total National Park Service recreation fee revenues. Senator Mike Enzi (R-Wyo.) has introduced legislation that aims to indirectly implement a surcharge on foreign visitors to national parks by raising tourist visa fees by $25 and increasing the electronic travel authorization fee by $16. Whether such a surcharge were implemented directly or indirectly, it could significantly increase total resources available to serve visitors.

Encourage experimentation in fee structures at individual recreation sites.

Innovations in pricing could yield useful data, increase revenue that can enhance recreation opportunities, and result in a more equitable fee structure by incorporating differentiated ticketing in terms of party size or visit duration, discounts for locals, or other tweaks. Currently, most sites with entry fees charge per vehicle rather than person, meaning an SUV packed with eight adults generally faces the same entry fee as a couple on their honeymoon. Small experiments in setting prices differently and using discounts or surcharges—whether implemented by residency, day of week, season, or otherwise—could grant useful insights for setting fees and provide resources to enhance visitors’ experiences on public recreation lands. At popular sites, particularly heavily trafficked national parks, promoting advance purchase of electronic tickets could decrease entry times and smooth transactions generally, making it easier for sites and units to experiment with different fee levels and structures. Granting more flexibility to local managers in setting fee structures, as noted above, would make experimentation more feasible and attractive.

Consider raising the price of the annual recreation pass.

The America the Beautiful Pass covers entrance and standard amenity recreation fees for all federal recreation lands and waters for 12 months. The current price of $80 does not reflect the immense value of our federal recreation lands and is priced much lower than alternative outdoor recreation opportunities. A family pool pass to the YMCA for only the summer months, for example, commonly costs two to four times the annual parks pass. In California, $80 would purchase annual access to only the state parks in the Lake Tahoe region. The secretaries of the interior and agriculture should consider raising the price of the annual pass and also consider building in an adjustment for inflation.

Conclusion

The recreation fee system is already helping many public lands flourish by providing significant revenue that helps improve management. Reforms to the fee system can allow visitors to empower even more public land units to flourish while also improving the feedback loop between visitors and managers, enhancing federal recreation lands for all who enjoy them.