In the spring of 1892, my grandfather, Pete Jensen, arrived in southeastern Montana, where he lived and ranched for the rest of his life. He had traveled with two other young men by horseback with all of his worldly possessions tied on the back of his saddle. The trip was arduous. A late-season snowstorm left them without food for three days. They were able to survive by cutting limbs from cottonwood trees and feeding them to the horses. Once they arrived in Montana, Jensen got a job as a ranch hand and in 1894 bought enough land to start the P.J. Ranch, which stayed in our family for 98 years.

To Jensen and other new arrivals from the East, the American West was a strikingly different world. Depending on the location and time of year, the West could be drier or wetter, hotter or colder, and more rugged than the eastern United States. Regional variation was also much greater. As economic historians Gary Libecap and Zeynep Hansen describe it, “The Great Plains could either be wet and lush or dry and barren, with no particular pattern,” which presented “unusual learning and adaptation challenges” for settlers from the East. Not only that, the economic demands placed on the region—and the responses of settlers to those demands—were rapidly changing as well.

To Jensen and other new arrivals from the East, the American West was a strikingly different world, which presented unusual learning and adaption challenges.

This meant settlers like my grandfather were constantly adapting to change. Three major forces drove the process. First, new and better information about the realities of the western landscape was continually becoming available, whether from on-the-ground knowledge developed through experimentation with different forms of farming and ranching or from better understandings of regional climate conditions.

Second, technology was ceaselessly advancing: The invention of barbed wire, the mechanization of haying, the introduction of new cattle breeds that were better adapted to harsh winters and dry summers—all of these were innovations that spurred change. Third, the institutions that governed the use of natural resources were evolving to match the realities of the West, at times formally and other times informally. These institutions included different forms of property rights to resources that, if well defined and understood, enabled settlers to resolve competing demands in mutually beneficial ways—but if left unclear and ill-defined often resulted in political or even physical conflict.

These monumental shifts and westerners’ responses to them demonstrate how new information, technological advancements, and institutional evolution have molded societies in the past. More than a century later, understanding that past helps illuminate the ways that ongoing change continues to shape the West and its inhabitants today.

Old West to New

It’s difficult to grasp the extent of the changes that were afoot when Pete Jensen arrived in Montana in 1892. At the time, eastern Montana was only a decade into its cattle-ranching era. Cattle had arrived in western Montana a few decades before, in the 1860s, serving as a food supply for hungry miners. Eastern Montana did not see a major influx until the 1880s. One frontiersman, Granville Stuart, reported that in 1880, “thousands of buffalo darkened the rolling plains,” but by “the fall of 1883, there were six hundred thousand head of cattle on the range.”

The early cattle grazing efforts were a process of experimentation and adaptation to new conditions. The first attempts involved turning large numbers of cattle loose on the open range and giving them little attention or care until there were enough four- and five-year-old steers to round up and send to market. Outside investors saw the open plains as a bonanza for beef production when the railroad reached Miles City, Montana, in 1882. Cattle ready for market could be driven to a railhead to be delivered to consumers in the East.

That world was undergoing a major transformation when Jensen arrived. The winter of 1886-87 killed thousands of cattle and put an end to the idea that settlers could simply turn herds loose on the range to mature until slaughter. It was becoming clear that a superior form of organization was owner-operators who put up hay and paid close attention to the condition of their cattle throughout the year. This type of operation rapidly replaced the open-range days of the 1880s.

Barbed wire, which was first produced commercially in the 1870s, became an important way to demarcate and enforce property rights. Ranchers quickly adopted the new technology, first using it to provide small pastures close to their dwelling places and to protect hay grounds. Extending it to encompass wider grazing areas was often more difficult, in part because of a lack of legal property rights to the open range. But the economic benefits associated with the invention of barbed wire were significant. Economist Richard Hornbeck estimates that between 1880 and 1890, barbed wire caused farmland values in the West to increase by 50 percent, an amount equal to as much as 3 percent of U.S. gross domestic product at the time.

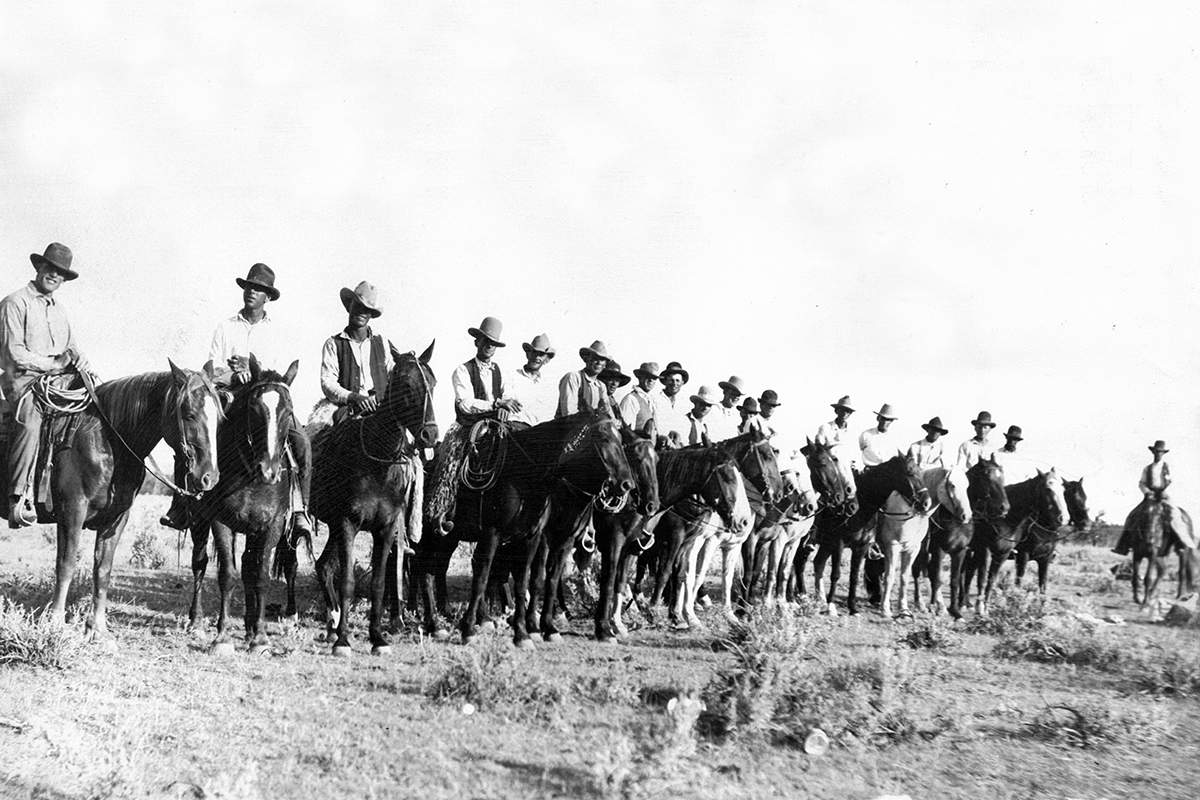

For the most part, the institutional framework faced by early settlers was a relatively open market with clear property rights to many resources. Cattle ownership was straightforward because livestock could be branded, which meant cattle could roam the open range and mix with the livestock of other owners. Each spring, roundups were held involving six to 12 ranches, with newborn calves receiving the brand of their mother. In the fall, another roundup was held, and beef cattle going to market were trailed to a railhead. In 1872, the Montana territorial legislature established a territory-wide brand registration system to record legal proof of cattle ownership. In 1885, this information became even more accessible when the Montana Stockgrowers Association published a brand-registration book, which lowered the costs of establishing ownership of cattle. Inspection facilities were created at the railheads or at the slaughter plants, with monies from cattle sales allocated on the basis of brands.

Establishing property rights to land was more vexing. Early settlers simply recognized informal property rights claims, such as squatters who settled in areas without following a legal process to obtain formal title. But as western settlement increased, informal claims often became less clear and more difficult to enforce. The primary mechanism for establishing a clear legal claim was through the various homestead acts. The initial act, established in 1862, granted 160-acre claims to homesteaders who lived on a plot for five years and made appropriate investments. Unfortunately, homesteading was ill-suited for cattle ranching in arid parts of the West, where 20 to 30 acres were needed to sustain a single cow per year. Even after the size of land claims were expanded to 320 acres in 1909 and then 640 acres in 1916, a homestead was not sufficient for a cattle operation, and ranchers often depended on the use of unclaimed open-range lands for livestock grazing.

By the early 20th century, a span of wetter-than-normal years convinced settlers that 160 or 320 acres was sufficient for an agricultural operation. The droughts of 1917-21 proved otherwise, and many homesteaders failed. Dan Fulton, a Montana cattle rancher and historian, reported that of the 70,000 to 80,000 settlers who homesteaded in Montana between 1909 and 1918, only 22 percent were able to “prove up” their claims and establish full legal ownership. The others, he said, “had starved out or given up.”

As this process of experimentation and learning unfolded, the institutions governing western resources continued to evolve. For example, ranchers made several attempts to address the tragedy of the commons on the public domain. In 1884, the National Cattle Growers’ Association urged Congress to provide a mechanism for leasing public domain lands for grazing. The pressure for maintaining opportunities for homesteaders, however, was politically popular. It was not until 50 years later, in 1934, that the Taylor Grazing Act established formal leases over wide swaths of grazing lands that had not been homesteaded. This created a complex mixture of federal and private lands in the West, often comprising relatively small parcels of private lands surrounded by larger areas of unclaimed federal lands leased for livestock grazing.

Ongoing Adaptation

Change continued in the decades that followed. The Great Depression of the 1930s, accompanied by several years of drought, forced numerous changes in ranch and farm operations, including the size of operating units. Mechanization was a major force, with tractors replacing teams of horses for many ranch functions, particularly haying. In conjunction with the reality that many homesteads were too small and eventually failed, mechanization also led to the consolidation of small farms into much larger ranches. As a result, many rural counties saw their populations decline significantly.

Powder River County, where Jensen ranched, reached its peak population of 3,909 in 1930. By 2018, it had fallen to 1,716. Other nearby rural counties peaked in 1920 and lost more than half of their residents over the following century. Improved roads and the arrival of the automobile meant that it was easier to drive longer distances for machinery repairs and groceries. This led to the closing of many retail stores, and medical care in small towns often ceased, with larger population centers building hospitals and providing a wider range of care. Some communities, previously thriving locations of stores and schools, completely vanished. Towns that served as county seats survived, but with many fewer services than before.

Just as Jensen and other settlers constantly adapted to change, so too must we continue to navigate the ever-changing natural world and shifting human demands placed on the West’s natural resources.

More recently, other changes have emerged, and with them have come both challenges and opportunities. For one thing, there are growing demands on the West’s natural resources, not only for their productive uses as commodities but also for “non-use” conservation purposes. Relatedly, demands for outdoor recreation opportunities are also increasing, partly a consequence of significant growth in urban areas that have boomed even as rural counties have dwindled in population.

The economics of ranching have also changed. Innovations like artificial insemination and genetic modification have required continued adaptation to longstanding practices. There has been increased pressure for many cattle ranchers in the West to sell to larger operations that can capture economies of scale—or, in some parts of Montana, to abandon ranching entirely and subdivide for housing development. Cattle ranching typically earns a low rate of return on invested capital, and there have been repeated attempts by ranchers to find other ways to supplement their income, including hunting leases, energy development, and ranch vacations.

Like my grandfather, westerners live in a landscape of ongoing change. Just as Jensen and other settlers constantly adapted to change, so too must we continue to navigate the ever-changing natural world and shifting human demands placed on the West’s natural resources.

[newsletter id=”18″ title=”Receive Our Print Magazine”]