This special edition of PERC Reports uses the hit television show “Yellowstone’s” portrayals of the Rocky Mountain West to examine real-world western issues. Explore the full issue here.

Monica Long, a character ostensibly of Crow or Blackfoot descent, is offered an associate professorship by the president of Montana State University in “Yellowstone’s” Season 1 (Episode 5). The position is in the university’s burgeoning Native American Studies program, an effort to boost representation in an area that the president describes as “underrepresented in academia,” to which Long offers a sardonic reply: “There’s an understatement.”

The nervous laugh of the well-heeled administrator in response leadenly reminds viewers of the trope of white cultural arrogance—a recurring, though gratifyingly multidimensional, theme in the series. The trope is not exactly false, but it skirts the complexities of real, historically shaped life.

Long, who teaches at a school on the reservation where she lives, turns down the job offer. “You don’t understand,” she says. “When a teacher leaves a school on a reservation, there isn’t a line of teachers to fill my place. There’s just one less teacher. If I leave, my kids will suffer, and they’ve suffered enough already.”

Long’s concern that taking the plum job would mean her grade school teacher position wouldn’t be filled is backed by the evidence: Reservation teaching positions have approximately double the national turnover rate, and recruiting teachers to reservation schools is notoriously difficult. The reason for this perennial shortfall is not, however, simply due to latent post-colonial discrimination—after all, similar teacher shortages plague rural, predominantly white communities as well. Rather, it is for the much more prosaic reason that for many prospective teachers, living on a poverty-stricken reservation holds as much appeal as a foreign assignment to, say, Malawi—interesting and even edifying, but not exactly a ticket to comfort and privilege. The poverty rate on reservations is double the national average, a reality that makes it disproportionately difficult to attract talent.

But where does this poverty come from? Is it inextricably woven into the fabric of Native American life—a malaise borne of colonial subjugation and crushed spirits? The argument certainly has its merits, and much ink has been spilled about the lingering effects of U.S. domination. In the kaleidoscope of variables that make modern reservations into “islands of poverty in a sea of wealth,” however, perhaps the most salient issue is the infantilizing “trusteeship” arrangement between the federal government and its “wards” in Indian Country. This anachronistic compact puts government managers in an oversight role, charged with managing Indian lands for Indian benefit—ostensibly because, according to the federal government, Indians were too “primitive” to look after their own resources. As a consequence, Indians are effectively prohibited from owning or investing in reservation land and homes or leveraging property for financial endeavors. This system is the grizzly in the room, overshadowing claims like colonialism, racism, or a “poverty mindset” as explanatory factors for reservation hardships. Investigative journalist John Koppisch summarizes it well:

To explain the poverty of the reservations, people usually point to alcoholism, corruption, or school-dropout rates, not to mention the long distances to jobs and the dusty undeveloped land that doesn’t seem good for growing much. But those are just symptoms. Prosperity is built on property rights, and reservations often have neither. They’re a demonstration of what happens when property rights are weak or non-existent.

Simultaneously patronizing and aloof, the Bureau of Indian Affairs, under Department of the Interior administration, has a long and dubious reputation for carrying out its self-professed “moral obligations of the highest responsibility and trust.” The agency has an annual budget of over $1.9 billion, employing some 4,500 government agents in 12 regional bureaus who are expected to “enhance the quality of life, promote economic opportunity, and carry out the responsibility to protect and improve the trust assets of American Indians, Indian Tribes, and Alaska Natives.” How well does it manage this noble, if nebulous, task? Not very well. In 1995, the Cherokee Observer noted pithily:

Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) has distinguished itself as the most corrupt, ineffective and abusive agency in the federal government. Although the BIA now professes the greatest respect for “tribal sovereignty” and “tribal self-determination,” there is precious little evidence of genuine concern for tribal autonomy in its administration of federal Indian policy. … By any standard, the BIA is a colossal failure as a government agency and the dead weight of its administrative wreckage represents the single greatest obstacle to the freedom, prosperity, cultural integrity and progress of Native Americans.

If the BIA achieved anything approaching its high-flown rhetoric, then we would expect the majority of Native Americans (who are free, as U.S. citizens, to live anywhere they please) to make prosperous, stable homes on reservation lands. In fact, only around one in five Native Americans chooses to do so. It seems that when people vote with their feet, they are inclined to judge government policy by its outcomes rather than its intentions. “Colonial exploitation,” in other words, may be more institutional than cultural.

In particular, federal policy vis-à-vis Native Americans creates a stultifying property rights regime driven in great part by bureaucratic self-preservation. As PERC research fellow Shawn Regan has written, the U.S. government “holds the legal title to all Indian lands and is required to manage those lands for the benefit of all Indians.” How this arrangement formed, and how it has historically evolved, is a long story, but suffice to say: It’s complicated. One way to begin to understand it is to look at a specific example of how Indian “property rights” were established, challenged, changed, and solidified on one particular piece of land.

Big Sunflower Hill

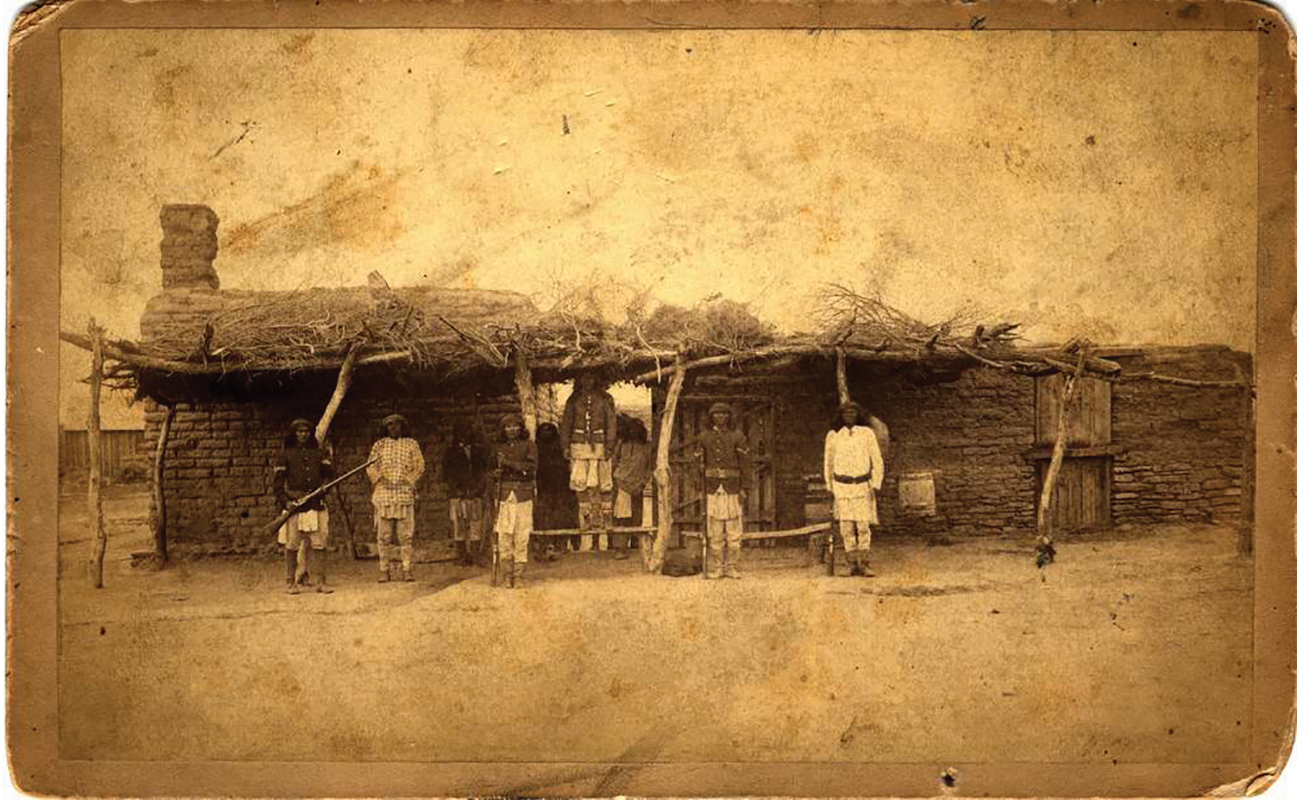

I happen to own 100 acres on the San Pedro River in southeastern Arizona. The property is a final vestige of our larger family ranch and includes Malpais Hill, known by the Apaches as Nadnlid Cho, or Big Sunflower Hill. Like all property, it has a convoluted pedigree, and like all land, it is not occupied by its “traditional” or “historical” inhabitants. It has been largely Anglo-owned since the early 1850s, but prior to that, it was contested territory between ingressing Apache and Spanish colonists and the more historically rooted Tohono and Akimel O’odham. Prehistorically, it was the hunting and farming grounds of the Sobaipuri—by some accounts the Uto-Aztecan-speaking forefathers of the famed Mexíca empire. A relatively rare ceremonial ball court is still evident in one of our northern pastures. It is also near the site of one of the final, and therefore best-documented, massacres of the last years of the Anglo-Indian Wars, a devastating 1871 rampage known as the Camp Grant Massacre.

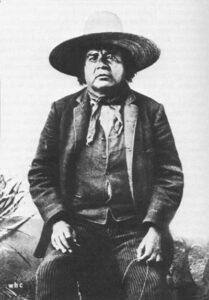

Haské ba ‘ntzin, also known as Eskiminzin, was a chief of the local Aravaipa band of the Western Apache who barely survived this episode of regional violence. Once he eventually recovered, he advocated for the establishment of and removal of his people to the San Carlos Apache Indian Reservation, where he felt they would be safe from the depredations of traditional enemies.

Some time after, Eskiminzin requested permission to move away from San Carlos. That he was freely allowed to do so perhaps indicates part of a strategic expansion of the reservation’s area—a common cause for both the Aravaipa Apache and the U.S. Army, which wanted to see “obedient” Indians rewarded. He gained U.S. citizenship in 1881. About that time, he is reported to have said: “I will go down to the Rio San Pedro and take some land where no one lives now, and I will make a ditch to bring water to irrigate that land. I will make a home there for myself and my family and we will live like the other ranchers do.”

This evidently came to pass, as land surveys from 1885 show Eskiminzin’s agricultural enterprises were well established and demarcated. The small settlement was attacked six years later, probably by Mexican and O’odham enemies, who carried off corn, wheat, and barley, destroyed a pumpkin crop and took more than two dozen head of cattle. It seems that Eskiminzin was successful enough as a rancher to have incurred the jealous wrath of neighbors and enemies alike. He and the survivors fled the attack. His land, though a lawful homestead possession, was forfeit under the more ancient rules of blood and force.

The saga that occurred on this hundred-acre parcel comes garbled through time, as so many are. An account from the 1930s by a University of Arizona graduate student, for instance, states the following, complete with the prejudices of its day:

As time passed the Government tried to move all of the Aravaipa Apaches to San Carlos. Chief Eskimizine and some of his followers objected and were allowed to stay on the San Pedro between Dudleyville and Mesaville. … Also several Indians held land on Aravaipa Creek about four miles above the San Pedro River. The Indians were not good farmers and had great trouble getting water out of the river onto the land.

We will never know the precise details, and to an extent they are irrelevant, since the vignette, conflicted as it is, nevertheless pushes back on some of the more popular myths and misconceptions about Native American land. For one thing, Eskiminzin’s story challenges notions of a monolithic “native sensibility” about land—clearly demonstrating that private property was not always and everywhere inimical to notions of a communal land ethos. While we should not gloss over the cultural conflicts, Eskiminzin apparently chose private agricultural initiative over government “trusteeship,” and he seemed to have prospered accordingly.

Such a story resonates to this day, with some outspoken Native Americans trying to point out that entrepreneurial self-sufficiency is in no way antagonistic to communal native values. Crow tribal member Bill Yellowtail puts it succinctly: “My reservation community will thrive in the 21st century only if we re-energize our traditions of private entrepreneurship and self-reliance.” Fully understood, Yellowtail’s comment, coupled with Eskiminzin’s story, may tell us more about modern reservation poverty than any of the 12 division heads of the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

There is a coda to the Eskiminzin affair: In 1919, a land title presented by Woodrow Wilson to “Pechula, a San Carlos Apache Indian,” granted him 80 acres immediately on the southern flanks of Big Sunflower Hill. It’s unclear if Pechula was directly related to Eskiminzin, yet local rumor is that the “Pechuli” allotment was to a U.S. Army Indian Scout for services rendered to the U.S. government. Eskiminzin’s son-in-law happened to have been a respected Indian Scout (later semi-mythologized as the Apache Kid), so a connection seems probable. Regardless, the land grant came with strings attached. According to the grant:

The United States of America … will hold the Land thus allotted (subject to all statutory provisions and restrictions) for the period of twenty-five years, in trust for the sole use and benefit of the said Indian … but in the event said Indian dies before the expiration of said trust period, the Secretary of the Interior shall ascertain the legal heirs of said Indian and either issue to them in their names a patent in fee for said Land, or cause said Land to be sold for the benefit of said heirs as provided by law.

The current ownership status on file with the county assessor’s office shows the owner of record as simply: “U.S.” As has been noted by PERC scholars Donald Leal, P.J. Hill, and Terry Anderson, along with others, a thing is not really “property” until it has all of three elements: definability, defensibility, and transferability. That the heirs of Pechula are, as best I can tell, unable to access or meaningfully transfer their nominal “property” effectively locks it away, along with any of the wealth-generating potential it may have. A fire recently burned across the parcel, and while the rest of the community helped fight the flames, no Pechula heirs showed up. It’s not clear if any of them are aware of its existence.

If just a small bit of probing into the history of a place reveals so much internal contradiction, one cannot help but wonder how much more of the standard narrative is badly understood.

Today, Big Sunflower Hill sits baking in the sun, oblivious to the historical dramas that swirl about its volcanic flanks. My family, as temporary custodian, dutifully pays the monthly electric bills to the BIA’s San Carlos Irrigation Project—a twist of bureaucratic fate worthy of a Pulitzer. Our kids, meanwhile, find potsherds and arrowheads on “our land.” But if just a small bit of probing into the history of a place reveals so much internal contradiction—and refutes so much of what is generally “known” about Indians and reservations—one cannot help but wonder how much more of the standard narrative is badly understood. The idea that Native American poverty is strictly the result of settler-colonialism seems, at best, an overly broad simplification.

Coming Full Circle

In the “Yellowstone” scene, Long turns down the associate professorship on grounds of loyalty to her local school and the kids that depend on her. A replacement would be hard to find. The reasons are complicated but are clearly linked to poverty. Brittany Roberts, a visiting volunteer teacher on the White Mountain Apache Reservation, writes that life for her is “somewhere between teaching in a small town, and teaching abroad.” She adds: “I live and work on a sovereign nation serving indigenous peoples, yet so much of what I do (and how people here live) is regulated or outright dictated by the U.S. government.”

Endemic problems like alcoholism, absentee fathers, and rampant unemployment are, not surprisingly, reminiscent of the social outcomes in other examples of command-and-control political models. Reservation governance in many cases combines the worst of distant, unresponsive bureaucracy with a tendency toward local corruption. For prospective teachers, hiring preferences for tribal members makes spouse assignments hard, and school funding is generally limited because much of the property is operated by the tribe—even if the U.S. government ultimately holds the title—and is therefore tax-exempt. At the end of the day, Long is right: Anyone wishing to take her place would be in a small, even ascetic, minority. Roberts also says that teaching on the rez is great “if you’re willing to trade a quiet, star-filled sky for being close to Target.” But she also notes, “Sadly, there’s a stark contrast between the abundance of natural beauty and the lack that many people here face. When I pass the multiple burned-down homes, as well as the trailers and houses with busted windows and crumbling roofs, I feel a pang of guilt.”

Guilt over reservation impoverishment is a predominant sentiment, no doubt, in most quarters of the rest of America. The poverty that plagues reservation life, however, cannot be glibly explained away under au courant notions of racist land dispossession alone—especially since some of America’s wealthiest individuals (like members of the Shakopee Mdewakanton, who operate various casino and gaming enterprises) also live on reservations. Explanations that chalk everything up to racism and land dispossession are insufficient on both historic and economic grounds. The muted national conversation on reservation poverty must be broadened. It needs to include the real harms that well-intentioned, yet counterproductive, government-mandated property schemes have on real—and really suffering—reservation members.