This special issue of PERC Reports explores the thorny issues of forest management, wildfire mitigation, and regulatory reform. Read the full issue.

Last summer, the Bootleg Fire in southern Oregon grew so intense that it created its own weather—“unpredictable winds, fire clouds that spawn lightning, and flames that leap over firebreaks,” as The New York Times reported at the time. The fire ultimately burned 400,000 acres and destroyed more than 100 homes, but it also provided a stark example of the benefits of forest treatments.

In an effort to preemptively reduce the impacts of large and costly wildfires, forest managers use treatments that remove fuels—brush, trees, and other flammable materials—to lessen the intensity of burns. The two most common fuel treatments are mechanical treatments and prescribed burns. Mechanical treatments use machinery to remove and rearrange vegetation in forests with the intent of reducing ladder and canopy fuels. Prescribed burns are planned fires that aim to achieve specific management objectives such as reducing fuel loads or improving habitat.

The U.S. Forest Service has not been able to undertake mitigation activities at the scale needed to address wildfire threats in a meaningful way.

Reports of the Bootleg Fire suggested that an area where scheduled prescribed burns had been delayed suffered more damage than areas where treatments had been completed. Firefighters also reported that where both types of treatments had been applied, fire intensity was reduced, the crowns of trees were left intact, and the blaze became a more manageable ground fire. While these approaches have proven effective, the U.S. Forest Service has not been able to undertake mitigation activities at the scale needed to address wildfire threats in a meaningful way.

Regulatory processes and litigation pose significant barriers to achieving federal mitigation goals. One survey of forest managers suggested that environmental policies are viewed as an important hurdle to prescribed burns, a key method of reducing fuels. Regulatory processes that increase the time between identifying and implementing treatments exacerbate wildfire risk and limit the flexibility of managers to use new information to quickly address emerging risk. In 2021, for example, several proposed treatment areas burned in large wildfires while facing delays from environmental review and litigation.

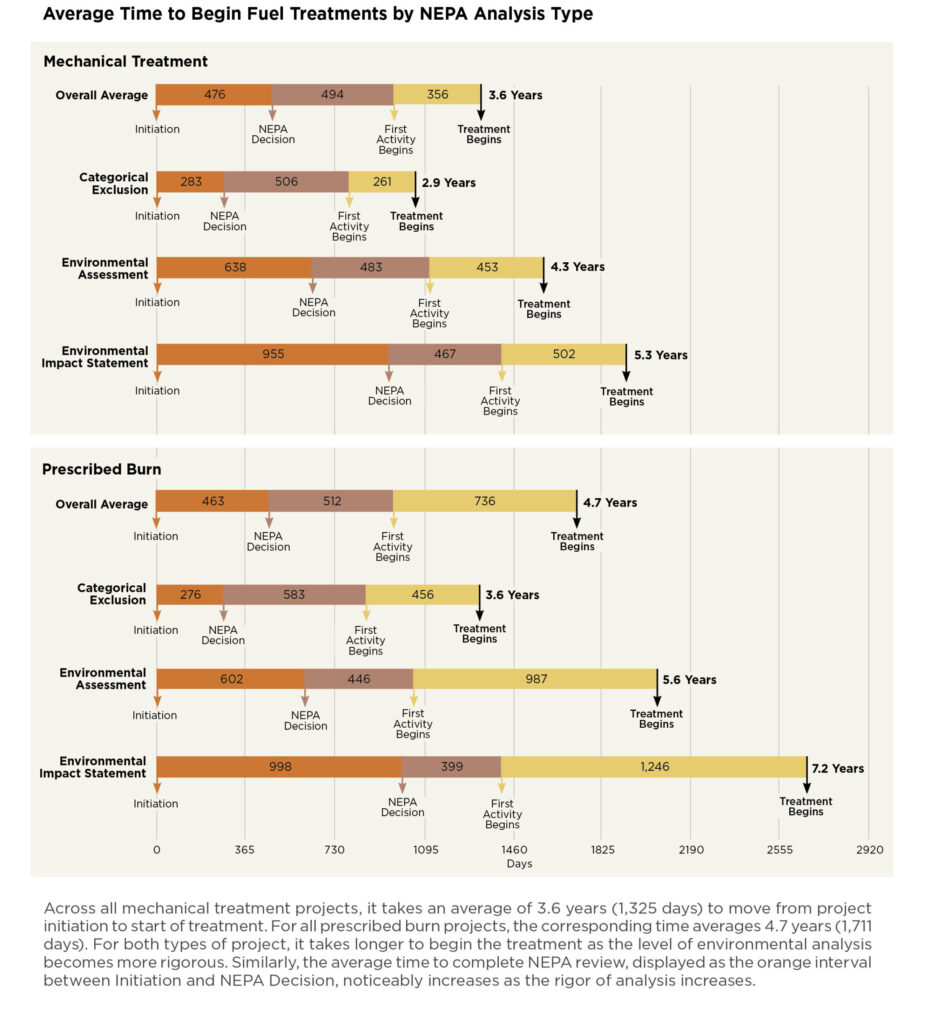

In a new PERC Policy Brief, “Does Environmental Review Worsen the Wildfire Crisis?,” we examine the amount of time it takes the Forest Service to implement fuel treatment projects while navigating the requirements of the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA). NEPA is a procedural law that requires federal agencies to assess the environmental impacts of proposed actions. Under NEPA, proposed projects undergo one of three types of analysis, in ascending order of rigor: categorical exclusion (CE), environmental assessment (EA), or environmental impact statement (EIS). While only some fuel-reduction activities require an EIS, the NEPA process can be time-consuming and resource-intensive for all projects.

Advocacy groups, firms, and the general public can file objections to NEPA decisions to the Forest Service and, once that avenue is exhausted, can also file lawsuits to overturn decisions or compel additional analysis. Although most projects are not litigated, the depth of analysis and time spent on the NEPA process is commonly based on the threat of litigation, as well as the level of public and political interest and defensibility in court.

Our recent report published by PERC compiles new NEPA data to examine the duration of administrative review for Forest Service wildfire mitigation activities. It documents how long it takes to implement fuel treatment projects and then separates out the portion that involves NEPA review from other factors, including litigation.

The Biden administration has proposed treating 20 million additional Forest Service acres to mitigate wildfire over the next decade. Changes in the process by which the Forest Service conducts environmental reviews and implements fuel treatments are likely needed to meet the ambitious goal. Our analysis shows that for projects that require environmental impact statements, the average prescribed burn takes 7.2 years before the first burn treatment begins, and the average mechanical treatment is not far behind at 5.3 years. Finding ways to reduce the 2.7 years mechanical treatments and prescribed burn projects spend, on average, in NEPA review for an EIS would help meet ambitious fuel-reduction targets.