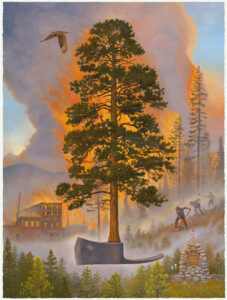

This special issue of PERC Reports explores the thorny issues of forest management, wildfire mitigation, and regulatory reform. Read the full issue.

We are living in the age of the megafire.

Fires that burn more than 100,000 acres are becoming commonplace in America. Nowhere is that more evident than in California. Throughout the 20th century, there were 45 megafires recorded in the state. In the first 20 years of this century, there have already been 35—seven in 2021 alone. The 2020 August Complex Fire in Northern California became the nation’s first “gigafire” since the Yellowstone Fire of 1988, consuming more than 1 million acres across three national forests.

Drought, fire weather, and climate change are all contributing factors. Less discussed, however, is how a single event in American history led to a century-old, failed government policy that delivered the primary cause of today’s crisis—too much wood in the woods.

Since the early 20th century, federal policy has been to suppress fires at all costs. Now most forests are incredibly overstocked with fuel as a result. And it can all be traced to the Great Fire of 1910, an episode known as the Big Burn.

The lead up to the Big Burn is a story unto itself. Since the late 1800s, presidents have created forest reserves—public forest land set aside to be protected and sustained. President Theodore Roosevelt, however, supercharged this effort by designating 150 national forests and establishing the U.S. Forest Service in 1905. The moves were not without controversy.

Some powerful members of Congress opposed the creation of a new agency, believing that Roosevelt was taking land away and denying economic opportunity. Further, at the time of the Forest Service’s creation, there was a split on how to manage forests. For some, fire was the enemy to be exterminated with militaristic gusto by green-shirted legions of new forest rangers.

A single event in American history led to a century-old, failed government policy that delivered the primary cause of today’s crisis—too much wood in the woods.

Others, though, knew that North American forests had evolved with fire for thousands of years. Tribes had used fire for select purposes, including protection, food supply, and the health of wildlife and ecosystems. Foresters in this camp recognized the value of “light burning,” which would clear out the understory, preempting huge, destructive treetop fires by setting cool, low-to-the-ground beneficial ones.

It was this “who” and “how” to manage our nation’s forests that provided the backdrop for the events of August 1910. Record low precipitation in April and May coupled with severe lightning storms in June and sparks from passing trains had ignited many small fires in Montana and Idaho. More than 9,000 firefighters, including servicemembers from the U.S. Army, waged battle against the individual fires. The whole region seemed to be teetering on the edge of disaster.

Then, on August 20, a dry cold front brought winds of 70 miles per hour to the region. The individual fires became one. Hundreds of thousands of acres were incinerated within hours. The fires created their own gusts of more than 80 miles per hour, producing power equivalent to that of an atomic bomb dropped every two minutes.

Heroic efforts by firefighters to save small mountain towns and evacuate their people became the stuff of legend. “The whole world seemed to us men back in those mountains to be aflame,” said firefighter Ed Pulaski, one of the mythical figures to emerge from the Big Burn. “Many thought it really was the end of the world.” Smoke from the Mountain West colored the skies of New England.

In just two days, the Big Burn torched an unfathomable 3 million acres in western Montana and northern Idaho, mostly on federally owned forest land, and left 85 dead in its wake, 78 of them firefighters. The gigafire-times-three scarred not only the landscape, but also the psyche of the Forest Service, policymakers, and ordinary Americans.

After the Big Burn, forest policy was settled. There was no longer any doubt or discussion. Fire protection became the primary goal of the Forest Service. And with it came a nationwide policy of complete and absolute fire suppression. In the years to follow, the Forest Service would even formalize its “no fire” stance through the “10 a.m. rule,” requiring the nearly impossible task of putting out every single wildfire by 10 a.m. the day after it was discovered. The rule would stay in effect for most of the century.

Bad events can create bad policy. Today, more than 100 years after the Big Burn, we are left with our current wildfire paradox: Decades of fire suppression have resulted in accumulated fuels that lead to larger and more severe wildfires that cannot be suppressed. Or as former Forest Service fire tower lookout Philip Connors has written, “By suppressing fire so successfully for so long, the public land agencies groomed the nation’s forests for the age of the megafire: a collision of climate change and tremendous, unnatural fuel loads.”

Fuel loads today are so dense and forests so radically altered that it is nearly impossible for there to be anything resembling a “natural” fire. Forest scientists studying the drivers of high-severity fire in the West have found that the fuel loads in our forests are by far the most important factor, followed far behind by fire weather, climate, and topography. Today, 63 million acres, or one-third of the land in our national forests—an area the size of Oregon—are at high risk of catastrophic wildfire.

Again, California is expositive. According to Ron Goode, tribal chairman of the North Fork Mono, prior to white settlement, Native Americans carried out “light burning” on 2 percent of the state annually. As a result, most forest types in California had about 64 trees per acre. Today, it is more common to see 300 trees per acre. This has led to a fiery harvest of destruction—bigger, longer, hotter wildfires. In 2020 alone, wildfires in California engulfed the equivalent of a Big Burn plus 1 million additional acres.

The Big Burn shaped the American fire landscape we have today. But even with a century of misguided forest management, there are promising signs we have turned the corner.

First, there is growing bipartisan recognition and scientific consensus that our forests need to be more actively managed through forest thinning and prescribed burning. Second, the Forest Service has released a 10-year “wildfire crisis strategy” with a goal of increasing by 20 million the acres treated in national forests, along with an additional 30 million acres on other federal, state, tribal, and private lands. Finally, there are serious ongoing policy conversations about addressing the barriers to accelerating forest treatments, including the regulatory hurdles, incessant lawsuits, permitting obstructions, and certification issues that are poised to stymie any large-scale forest restoration strategy.

The Big Burn of 1910 will always be with us. We will never fully escape the consequences of government policies that were solidified while the ashes of forests in Idaho and Montana smoldered. But today’s “age of the megafire” can be an equally historic catalyst toward a new future for our forests, one that more closely mimics nature and the practices of those who lived closest to the land. That is how we will fix America’s forests.