Electricity generation from wind energy in the United States has increased 56-fold over the past two decades and now accounts for just over 8.4 percent of the country’s total utility-scale power generation. Growth of the onshore wind sector, however, threatens bird populations in some regions of the country due to incidental injury or death and reduced natural productivity. Total bird deaths from collisions with turbines are estimated to be between 140,000 and 328,000 per year, including thousands of eagles, hawks, owls, and other raptors. These numbers are likely to increase, as the Department of Energy aims to have wind energy meet 20 percent of electricity demand by 2030 and 35 percent of demand by 2050. A number of states also have renewable energy targets likely to be met, at least in part, by increasing the number of onshore wind farms, the source of more than 99 percent of current U.S. energy generation from wind.

Bald and golden eagles are protected by federal law, and the government offers permits for incidental take—unintentional deaths—of the species resulting from wind power generation. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service reviews permit applications and considers the level of sustainable take for each regional eagle population. Permits require a one-time fee as well as additional fees for five-year reviews and renewals. Regulatory changes in 2016 extended the timespan of eagle-take permits for wind projects from five to 30 years and increased the allowable incidental take without requiring compensatory mitigation from 1,000 to 4,200 bald eagles over the life of each permit. Extending the duration of permits was done with the interest of wind energy development in mind, providing longer-term certainty for such projects. Project owners are not required to possess a permit but face heavy fines and possible criminal charges if caught taking an eagle without a permit.

The current permitting system, however, uses an inefficient, one-size-fits-all approach. Permits have a fixed cost, allow for a maximum number of incidental deaths, and are not transferable. By contrast, a transferable permit system that accounts for marginal incidental take of eagles at wind farms would allow for increased growth of the sector while limiting the overall threat to the birds. By effectively creating a market for eagle take, wind energy producers would be forced to consider the marginal cost of killing an eagle and adjust their behavior accordingly. They would essentially balance the cost of reducing the risk of killing an eagle against the price of a permit that would be required if an additional eagle were killed. Such a policy would create a tradable property right and could generate cost-effective eagle conservation if the market were sufficiently competitive and transaction costs were low.

Shifting from a standards-based system of non-transferable permits and fines to a tradable permit system would yield several benefits. As demonstrated with pollution control policy, standards are rarely efficient or cost effective. In the case of pollution, a system based on standards treats different sources with different abatement costs and different impacts on their surrounding environments the same. With eagle incidental take, all wind projects are subject to the same type of permit, regardless of the particular risk a given project has of killing eagles—a risk that may vary according to location and turbine design, among other factors. Thus, a project that might end up incidentally killing 10 eagles a year pays the same permitting fees as one that takes 50 per year, decreasing any incentive on the margin to reduce incidental take.

In pollution control, transferable permits allow firms that emit less than their allowable level to sell excess permits to other firms that are interested in expanding operations or face higher abatement costs. Such a system provides a cap on overall emissions while also giving firms an incentive to operate more cleanly, as they can profit from selling excess permits. In the context of eagle take permits, the current system can only cap the overall incidental killing of eagles if no new permits are allocated. If the overall take were limited—and no new permits were allocated to new projects—expansion of wind projects would be constrained to lower-risk areas, many of which are also less efficient in terms of wind energy production or lack transmission infrastructure.

Transferable incidental take permits could limit the overall number of eagles killed annually while encouraging wind energy generators to decrease take by locating in lower risk areas, altering turbine design, or implementing other mitigation measures to reduce risk. The system would also motivate permit holders to monitor take by non-permit holders. Ultimately, a transferable permit system for take would let the market encourage conservation of eagles rather than having the government set an inflexible flat rate for take of eagles over a 30-year timespan.

Highlights

- The current permitting system for incidental take of eagles uses an inefficient, one-size-fits-all approach that eliminates any incentive for a wind farm to conserve eagles beyond its individual permit cap.

- A transferable permit system would allow for increased growth of the wind energy sector while limiting the overall threat to eagles. By effectively creating a market for eagle take, wind energy producers would be forced to consider the marginal cost of killing an eagle and adjust their behavior accordingly.

- Transferable incidental take permits could limit the overall number of eagles killed annually while encouraging wind energy generators to decrease take by locating in lower-risk areas, altering turbine design, or implementing other mitigation measures to reduce risk.

- A transferable permit system would let the market encourage conservation of eagles rather than having the government set an inflexible flat rate for take of eagles over a 30-year timespan.

Recommendations

- Create tradable permits for incidental take of eagles.

- Establish a trading system and maintain third-party monitoring to provide accountability.

- Expand the permitting system to include transmission line owners.

Eagle Protections and Threats

Congress passed the Bald Eagle Protection Act in 1940 and revised it in 1962 to include golden eagle protection as well. The law prohibits “take, possession, sale, purchase, barter, offer to sell, purchase, or barter, transport, or export/import of any eagle, alive or dead, including any part, nest, or egg, unless allowed by permit.” The term “take” is defined to include “pursue, shoot, shoot at, poison, wound, kill, capture, trap, collect, molest or disturb.” In 2009, regulations issued by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service allowed for limited, permitted take that occurs in the course of otherwise legal activity and cannot practicably be avoided, often called incidental take. The agency revised its regulations in 2016 to extend the maximum duration of new permits from five years to 30 years but still allowed for issuance of five-year permits. Under the 30-year permits, wind companies are allowed to kill or injure up to 4,200 bald eagles per permitted project over the life of the permit without penalty, up from 1,000 under five-year permits. The initial application processing fee is $36,000 for all eagle take permits, whether the duration is for five years or longer. Longer-term permits are reviewed every five years at a cost of $8,000. The 2016 revised regulations included a requirement that wind energy companies pay for independent third-party monitoring of all permits, reporting directly to the Fish and Wildlife Service, at these five-year intervals. Prior to the 2016 revisions, companies had the option to self-monitor by reporting to the agency themselves.

Federal regulations include both civil and criminal penalties for unpermitted take as well as for violation of permit conditions, and several companies have been fined for taking eagles without permits. In early 2022, the federal government fined electric utility NextEra Energy $8 million for killing 150 eagles over the past decade at wind farms owned by the company in eight states. In 2013, Duke Energy agreed to pay a fine of $1 million, as well as $900,000 in restitution and compensatory mitigation, in a settlement for killing 14 eagles and 149 other protected birds at two wind farms in southeastern Wyoming between 2009 and 2013. In 2014, PacifiCorp was fined $2.5 million for killing 38 golden eagles and hundreds of other protected birds at its wind farms in Wyoming.

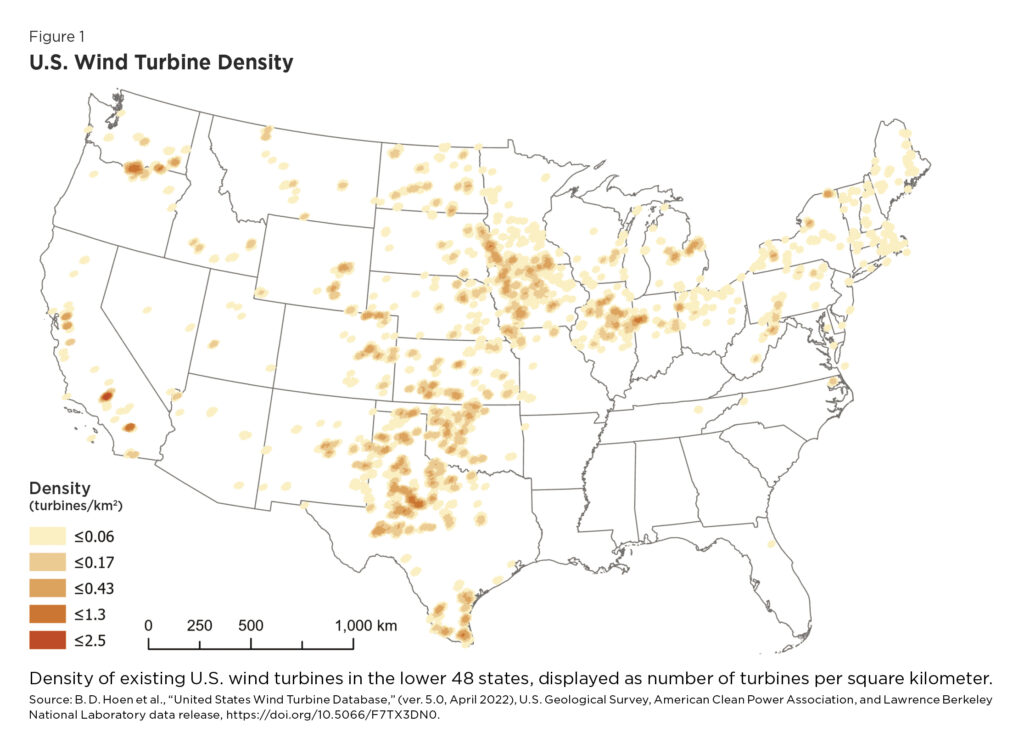

Figure 1 shows the spatial density of existing wind turbines in the lower 48 states to illustrate the relative significance of wind energy across the country.

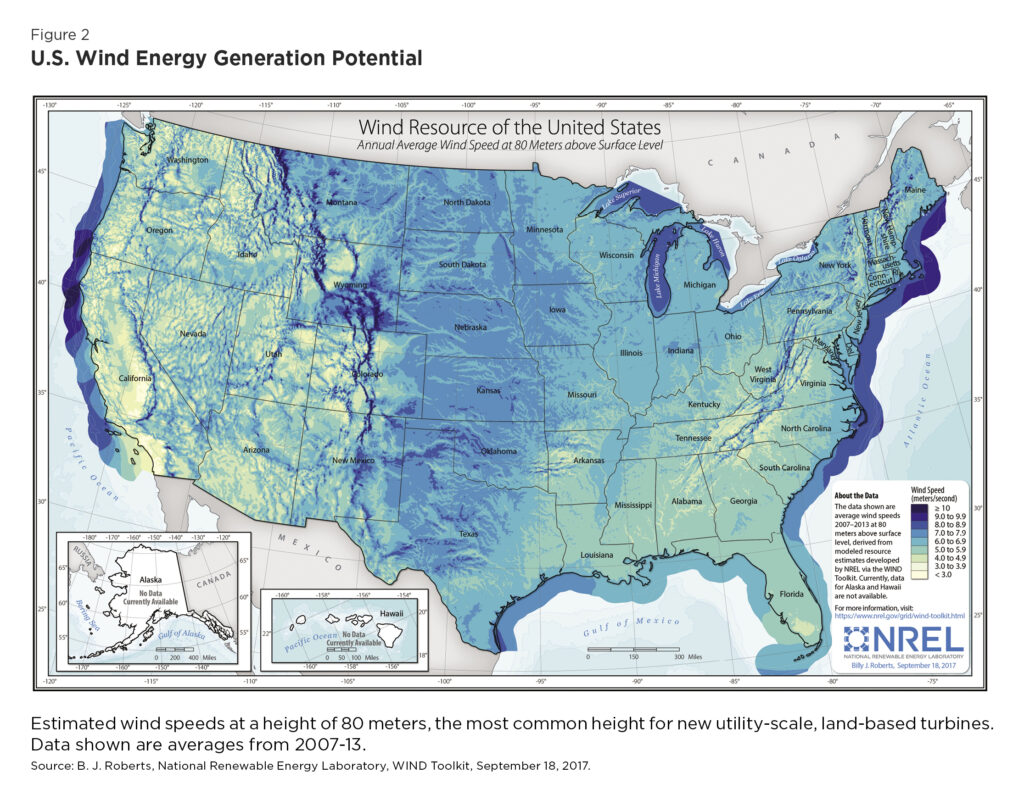

Figure 2 shows wind energy generation potential in the continental United States based on wind speeds at 80 meters, the most common height for new utility-scale, land-based turbines.

Biological Considerations

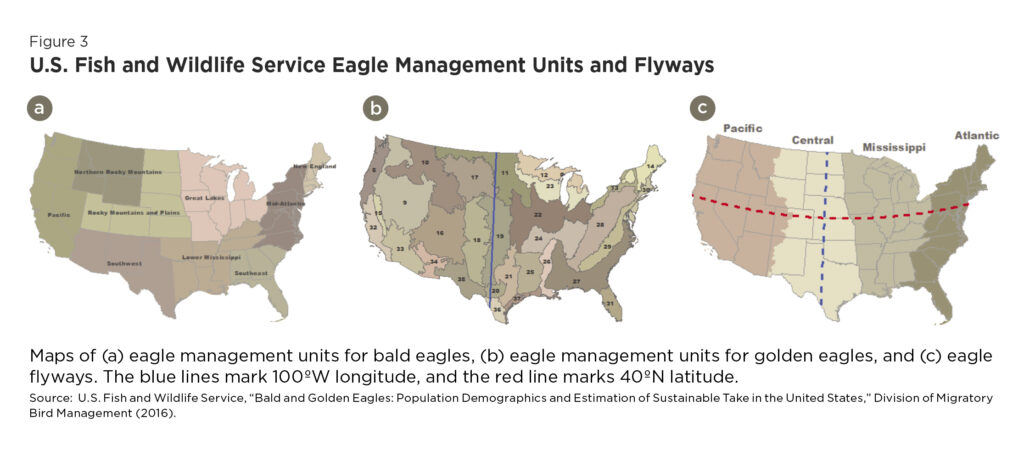

The Fish and Wildlife Service has designated eagle management units (EMUs) for both the bald and golden eagle as well as management designations by flyway. There are nine EMUs for bald eagles and 32 for golden eagles, excluding Alaska. The four flyways are the Pacific, Central, Mississippi, and Atlantic. Figure 3 displays the management units and flyways. The Fish and Wildlife Service conducts population and nesting surveys and estimates natural and anthropogenic mortality by EMU as well as within subunits of local area populations. Incidental take permits are issued only in accordance with the goal of sustaining or increasing populations for all areas. Take permits and associated management plans submitted by power companies must address potential effects of a wind project on eagle mortality and nesting impairment. The Fish and Wildlife Service has estimated that in the case of golden eagles, even current levels of take may not be sustainable. As a result, rules have been modified to include compensatory mitigation for incidental take of golden eagles. Compensatory mitigation must reduce another form of eagle mortality by an equal or greater amount or increase the eagle population by an equal or greater amount.

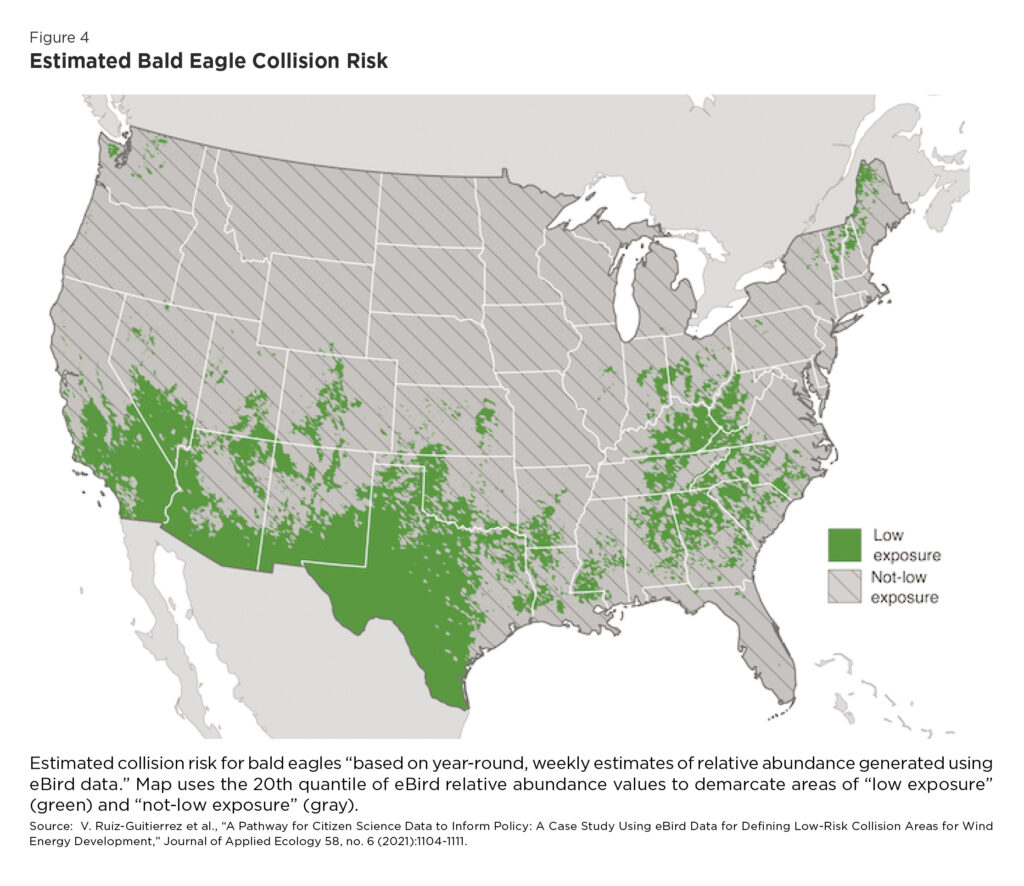

The relative significance of anthropogenic mortality increases with eagle age, accounting for about one-third of hatchling-year deaths and nearly two-thirds of adult mortality for golden eagles. Collisions and electrocution accounted for more than half of anthropogenic hatchling-year deaths but only about a quarter of anthropogenic adult mortality between 1997 and 2013, based on a study of tagged golden eagles. Overall mortality from collision—which includes collisions with anything, not necessarily a wind turbine—and electrocution, typically from contact with electricity transmission lines, were about the same. One recent study used relative bald eagle abundance data collected through eBird citizen surveys to define quantiles of exposure to collision risk for the continental United States. Areas of lowest collision risk tend to be in the desert Southwest and southern Appalachian regions, as shown in Figure 4, areas that also have low wind energy potential based on wind speeds.

A Solution that Harnesses Market Principles

In contrast to the current system, a transferable permit program for incidental take of eagles at wind farms would effectively create a market for eagle take, forcing wind energy producers to consider the marginal cost of killing an eagle and adjust their behavior accordingly. Market-based solutions have been implemented to address environmental problems in a variety of contexts, including the trading of sulfur dioxide and nutrients to control air and water pollution, respectively. Similarly, bycatch quotas for marine fisheries have been used to reduce incidental catch of non-target species.

Under a market-based solution for eagle take, an overall limit for allowable incidental take could be set compatible with biological estimates of sustainable anthropogenic harvest limits to protect eagle populations. Permits for incidental take could then be traded among wind energy projects to allow for a more efficient distribution of take rights. Under the current non-transferable system, in areas facing unsustainable take, protection of eagles and expansion of wind energy are mutually incompatible goals. A tradable permit system would incentivize new or expanding wind farms to reduce their risk of eagle take. Overall take would remain capped, while trading of permits would allow new wind energy farms to be built or existing projects to be expanded—provided new or expanding firms bought enough permits to reflect their levels of expected incidental take. Firms selling permits would need to ensure they took fewer eagles than their permits allowed or undertake actions to reduce their expected take. The permit price in equilibrium would reflect the marginal cost of avoiding the incidental take of an eagle.

Adaptations to Limit Incidental Kills

Wind energy companies can take various measures to reduce or avoid incidental eagle take, including siting changes and on-site modifications. Wind energy firms can reduce kills by avoiding areas of high use by eagles or high-risk topography, or by reducing the number of turbines in such areas. However, to the extent that these are also areas of higher wind, avoidance reduces generation efficiency. Another relatively high-cost mitigation measure is shutting down turbines when eagles are at risk of being taken. New artificial intelligence technology can identify eagles and other protected birds at wind projects through on-site cameras that can then automatically shut down certain turbines, but shutdown takes some time, means loss of energy during shutdown, and entails restarting costs.

Less expensive mitigation measures include installing pylons to divert birds around projects or using systems that emit acoustic signals to alter flight paths when birds are detected nearby. Likewise, nests can be removed and nest building can be inhibited to deter eagles from locating in higher-risk areas. Painting one turbine blade black was found to reduce avian death by 72 percent in a recent study in Norway. Finally, attractants such as carrion, perches, and anything that draws eagle prey can be removed.

Transmission collision and electrocution deaths can be reduced by putting protective insulation on wires and conductors, spreading wires farther apart, adjusting pole placement, installing barriers or extensions on poles to make perching safer, and marking power lines with reflectors or ultraviolet materials highly visible to eagles. All of these measures decrease mortality risk for other raptors as well. The Fish and Wildlife Service provides guidance on best management practices to reduce eagle take that include these mitigation techniques, and wind projects are required to develop and implement eagle management plans.

Recommendations

A transferable permit system for incidental take of bald and golden eagles would allow for increased growth of the onshore wind energy sector while reducing the overall threat to the species.

1. Create tradable permits for incidental take of eagles.

The first steps to implementing a tradable permitting system would be to determine the overall allowable take and who gets permits. In addition to issuing incidental take permits, the Fish and Wildlife Service monitors bald and golden eagle populations and periodically updates estimates of populations, natural and anthropogenic mortality, and sustainable mortality in light of population targets for various regions of the country. The agency would thus be the natural source to establish a tradable permitting system, set overall sustainable take, and determine the number of permits to allow. In new market-based pollution control systems, the initial allocation of rights is often controversial, as the distribution of permits grants valuable rights to some firms but not others. In the case of eagles, however, some existing firms already have rights to certain levels of allowable take, with a set number of years remaining to the rights for each firm, varying depending on when a permit was initially granted. Existing permits, therefore, could be transformed into a tradable right.

Once rights are tradable, firms have an incentive to reduce the chance of eagle mortality within their projects to the extent there is a demand for permits to support industry expansion. If an incidental eagle death were to occur at a wind project without a permit, that firm would have to buy a permit from another firm to avoid an increase beyond allowable take. If a project caused more incidental deaths than it held permits for, it likewise would have to buy a permit from another firm to offset the excess deaths. If an area were at the limit of sustainable take, industry expansion could only occur if new projects bought incidental take permits from existing permit holders according to their expected risk of incident, because the Fish and Wildlife Service would not issue permits beyond sustainable take. This model would give both existing wind energy firms and new entrants an incentive to reduce risk of incidental take and balance investment in avoidance against the cost of buying a permit.

In areas where combined natural and anthropogenic mortality is below the sustainable level, expansion could occur more readily as the Fish and Wildlife Service could issue new permits to the extent it deemed it biologically sustainable. There could still be a positive market price for permits, as some firms operating without permits may incidentally kill eagles, necessitating purchase of a permit from another firm. Thus, where there is leeway biologically, the Fish and Wildlife Service could sell new permits at the market price and generate revenue to support permit program operations. On the other hand, if the Fish and Wildlife Service found an area beyond the sustainable take level, it could buy permits to take them off the market, encouraging selling firms to invest more in mitigation while the eagle population returned to a sustainable level over time.

While there is significant overlap between existing wind farms and eagle abundance, there is also significant wind energy generation potential in areas of lower eagle abundance. Firms that wanted to expand within higher collision-risk areas would need to balance the added risk of eagle kills and permit costs against the greater efficiency of locating in the higher-risk areas, or consider expansion in alternative areas of lower collision risk.

2. Establish a trading system and maintain third-party monitoring to provide accountability.

Establishing a trading system, monitoring trades, and maintaining effective third-party monitoring of take would be essential to a shift to a market-based system. Costs of monitoring eagle take are likely to be similar under a tradable permit system as under the current system. Third-party monitoring of mitigation and take is already in place and could be required for all wind farms under a new system. Monitoring of trading could be done electronically and at low cost. Trading of sulfur dioxide permits, for example, is managed by the Environmental Protection Agency through the Clean Air Market Division’s Business System, where users can make trades online. Firms holding permits would have a strong incentive to document their ownership of eagle take permits, particularly in the event of an incidental kill. These permit holders would also have an incentive to monitor and report incidental take by non-permit holders, an incentive that does not exist under the current system.

Trading zones would likely need to be created to account for regional variation in eagle populations. For bald eagles, this might not affect efficiency of the permit markets significantly, as the Fish and Wildlife Service currently sets regional take thresholds for each species. There are far more EMUs for golden eagles though, which could restrict trading to inefficiently small markets. However, it could be biologically feasible to trade permits within each of the four eagle flyways, with a hard cap on take in management units with the most vulnerable populations. Permit market efficiency would likely increase with larger numbers of both potential buyers and sellers.

3. Expand the permitting system to include transmission line owners.

An additional consideration in the protection of eagle populations is the increased risk of electrocution with expansion of high-power transmission lines. According to recent research, to meet the Biden administration’s goal of net zero emissions by 2050, the United States will need to increase electricity transmission capacity by 60 percent by 2030 and nearly triple it by 2050. Already, electrocution from transmission lines was the cause of 50 percent of golden eagle and more than 10 percent of bald eagle fatalities measured between 2006 and 2011. Hence eagle mortality from electrocution is likely to be of equal if not greater significance than mortality from wind turbines in the coming decades, yet transmission line companies are not currently required to obtain incidental eagle take permits. In light of that reality, it could be prudent for a transferable take permit system to be expanded to include transmission line owners as well.

Conclusion

The Biden administration has set a goal of 100 percent carbon-free energy in the power sector by 2035, with primary focus on wind and solar energy sources. Reaching that aim would entail an increase from about 40 percent carbon-free electricity generation currently, less than a quarter of which is from wind. Even moderate progress toward such a goal would necessitate significant expansion of wind energy production. Perhaps in recognition of both social and environmental externalities associated with onshore wind energy expansion, the administration’s recently unveiled infrastructure plan focuses on offshore wind energy. Development of offshore wind power, however, is technically more difficult and expensive than onshore and often faces opposition from nearby residents, the commercial fishing industry, and even environmental groups concerned about negative impacts on local species. Thus, political and economic pressure will likely also continue for onshore expansion to help meet the lofty clean energy goals.

Under the current system of regulating incidental eagle take, there is no denying that the growth of onshore wind farms will increase eagle mortality. Existing firms with permits have little incentive to reduce take on the margin, and current fines for unpermitted take—unless increased—will be less influential in the face of rising value of wind energy production.

The proposed alternative, a tradable take permit system, caps allowable take to maintain sustainable eagle populations while also providing the incentive for firms to invest in mitigation to reduce risk of incidental eagle kills. Mitigation can be in the form of onsite investments to reduce mortality as well as siting new wind turbines in locations that might be less efficient for wind energy generation but would also reduce risk to eagles. Firms would be expected to begin with the lowest-cost mitigation measures and progress to more expensive measures if demand for expansion continues and the returns to wind energy generation rise.

When the marginal cost of killing an eagle is zero, as is the case under the current permit system, there is little incentive to reduce take on the margin. Imposing fines for incidental kills forces a firm to consider that cost but does not provide any incentive to mitigate take below the firm’s cap. Absent changes, an increase in the market value of wind energy will encourage industry expansion and put eagle populations—and other birds generally—at increased risk. A tradable permit system internalizes the cost of incidentally killing an eagle, effectively creating a positive value for eagle conservation. Further, the market provides compensation for firms for the cost of mitigation or offsetting actions, while also ensuring a limit on overall allowable take. Property rights are the key to incentivizing reduced mortality and allowing industry growth without damaging eagle populations.