This special issue of PERC Reports explores the West’s water crisis and how markets can address today’s shortages. Read the full issue.

In 2004, Mike and Chantell Sackett purchased a lot in a residential subdivision near Priest Lake, Idaho, where they planned to build their dream home. When they graded the lot to prepare it for construction, however, that dream was abruptly put on hold. An official from the Environmental Protection Agency ordered their crew to stop their work. A few weeks later, the agency sent the Sacketts a compliance order accusing them of filling a federally regulated wetland without a permit. The order demanded they restore the wetland to the EPA’s satisfaction—or else face fines of up to $75,000 per day and possible criminal prosecution.

That order has spawned a 15-year fight between the Sacketts and the EPA over whether the property is covered by the notoriously unclear Clean Water Act. The law established federal authority over “navigable waters,” but Congress unhelpfully defined “navigable waters” as the “waters of the United States.” It has never said what, beyond actual navigable waters, this phrase is supposed to include. Thus, regulators, landowners, and conservationists have been left to guess what counts under the act.

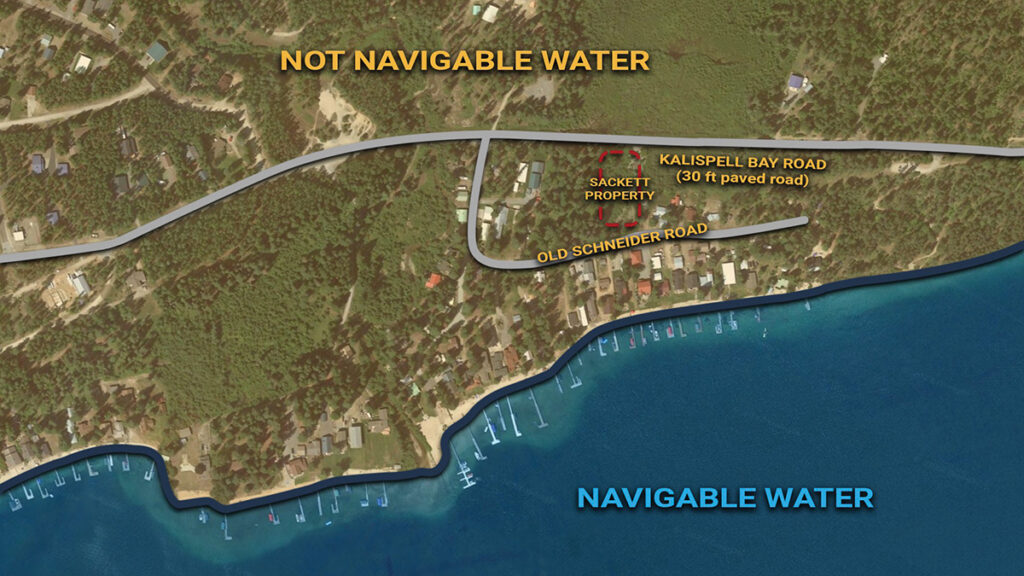

In the Sacketts’ case, the EPA says their land is covered because it contains a wetland that is similar to another wetland across the street, and that other wetland drains into a man-made ditch, and that ditch connects to a creek, and that creek empties into Priest Lake, which is navigable. The Sacketts respond that if such Rube Goldberg-esque theories suffice, no landowner can know whether their land is regulated. After all, when they purchased the lot, it seemed no different from the neighboring lots that had been developed without objection.

Despite repeated calls from landowners, regulators, and even the Supreme Court, Congress has never elaborated on “waters of the United States.” Instead, legislators have left the EPA to figure it out through a series of interpretations of the phrase.

In October, the U.S. Supreme Court heard the Sacketts’ challenge to the EPA’s assertion of authority over their land. This marks the second time the Sacketts have been to the Supreme Court, having won a unanimous decision in 2012 that they had a right to challenge the EPA’s order. If the court finally brings some clarity to the Clean Water Act’s cryptic terms, it would obviously benefit hapless landowners like the Sacketts. But it would also benefit conservation efforts by reducing conflict, better focusing federal enforcement efforts, and encouraging states and private conservation groups to make wetlands an asset rather than a liability for private landowners.

A 50-year Quagmire

A half-century after the Clean Water Act was enacted, there’s still no clear answer as to what it regulates. Despite repeated calls from landowners, regulators, and even the Supreme Court, Congress has never elaborated on “waters of the United States”—sometimes abbreviated as WOTUS. Instead, legislators have left the EPA to figure it out through a series of interpretations of the phrase, all of which have been struck down by courts as too broad, too narrow, or simply arbitrary.

The Supreme Court has considered the meaning of waters of the United States several times, only siding with the EPA once. But those cases have usually concerned extreme examples that shed little light. The court has held, for instance, that the Clean Water Act covers a wetland on the shore of a navigable lake if it is unclear where the lake ends and the wetland begins. And the court has said that if migratory birds land in a remote, flooded gravel pit, then the pit is covered under the act. But there is a vast number of water features, soggy lands, and other areas between these two extremes that have been left unresolved.

When the court confronted a more difficult situation, in a 2006 case called Rapanos, it fractured and produced no majority opinion. The late Justice Antonin Scalia, writing for four justices, interpreted the Clean Water Act to reach only a) navigable waters; b) relatively permanent, standing, or continuously flowing tributaries of navigable waters; and c) wetlands with a continuous surface connection to a navigable water or regulated tributary. Justice Anthony Kennedy, writing only for himself, however, interpreted the act to apply to any water or wetland with a “significant nexus” to a navigable water. Four other justices dissented, favoring an even broader interpretation of EPA’s power.

Because there was no majority opinion, Rapanos has only increased confusion and uncertainty. The EPA has generally favored Justice Kennedy’s significant nexus approach, but it has struggled to convert that into a real standard. Each of the last three presidential administrations have issued regulations attempting to define waters of the United States more precisely. But each of those regulations have been upended by courts, causing the EPA’s approach to dramatically change from year to year and state to state. Ultimately, Justice Kennedy even soured on the approach, suggesting in one of his final arguments before his retirement that the Clean Water Act is so vague that it may be unconstitutional.

Bogged Down in Bureaucracy

In many ways, the Sacketts’ case gives the court a do-over for Rapanos, at least when it comes to federal regulation of wetlands. If a majority of justices can coalesce around a particular approach, they will finally give some clarity to the agencies, regulated landowners, and environmentalists with an interest in stream and wetland conservation.

Assuming the court adopts a clear but narrower interpretation of the Clean Water Act, what would this mean for wetland conservation? In an amicus brief supporting the Sacketts, PERC argued that vague federal regulation is no panacea for conservation. It can cause federal enforcement efforts to be unfocused or haphazard, make wetlands a liability for private landowners, and breed ill will between landowners, conservationists, and regulators. This can ultimately discourage wetland conservation and restoration. A clear rule, on the other hand, gives states, landowners, and conservation groups certainty where their conservation efforts are needed and helpful.

It is not a coincidence that so much of the conflict over the Clean Water Act has concerned wetlands. Navigable waters and the land underlying them are public property, subject to a federal servitude for navigation, and are governed by the public trust doctrine. Thus, no one would reasonably expect that they could pollute or fill the Chesapeake Bay or Mississippi River without government permission, and no one’s rights are curtailed if the government refuses to issue a permit.

Wetlands, on the other hand, are mostly found on private property. According to the EPA, 75 percent of wetlands in the lower 48 states are privately owned. Yet most landowners would struggle to identify wetlands because, according to the Congressional Research Service, the EPA’s interpretation of wetlands includes areas that “either may have wetland characteristics only some portion of the time, or may not look like what many people visualize as wetland.” Moreover, the activities being regulated—home building, farming, and logging—are not the sort of intrinsically harmful activity, like dumping traditional pollution into a stream, that people expect to require federal approval.

When landowners discover that they might need a federal permit, the process for obtaining one can be extremely costly and time-consuming. Because the act’s application, under the current significant nexus approach, cannot be determined by simply looking at the property and public sources of information to determine whether an area is regulated or not, the landowner must hire one or more experts to make an assessment. According to EPA estimates, permit applicants spend between $1 billion and $1.6 billion on these costs annually. But this is only the beginning of the expense. If a permit is granted, the EPA may demand mitigation that can cost more than $500,000 per acre. Therefore, the presence of a wetland potentially regulated by the act can be a significant liability for landowners.

For Peat’s Sake

The Clean Water Act regulates all discharges to and filling of waters of the United States, including activities that improve the environment. For example, this burdensome process can penalize landowners who maintain or restore wetlands on their property, discouraging them from making such investments.

In 2012, Wyoming landowner Andy Johnson dammed a small stream on his property to create a pond for his daughters’ horses and other livestock. The stream had been heavily eroded by decades of livestock use by prior owners. Johnson worked with the state to design the pond so that it would help to restore the stream’s function and produce other environmental benefits, including restoring habitat for fish and wildlife, improving water quality by removing sediment, and creating a ring of wetlands around the pond. By all accounts, the project was a success. Nonetheless, the EPA issued a compliance order against Johnson because he did not get a federal permit before damming the trickling stream.

For two years, the agency subjected the Johnsons to the same treatment as the Sacketts, threatening significant fines and imprisonment if the family didn’t rip out the pond. It did so despite never questioning the environmental benefits that had been created. In the end, the Johnsons sued the agency, which promptly settled once the family proved that the stream had no connection to navigable waters. Despite the happy ending, the ordeal was not something any other family considering a similar restoration project would want to experience.

Or consider the “permitting hell” that Scott and Sandy Campbell, owners of Silvies Valley Ranch in Oregon’s high desert, went through after restoring a watershed on their property. To mimic the impacts that beavers had historically had on the ecosystem before being extirpated decades earlier, the landowners created artificial beaver dams in a desert gully that flowed only a few weeks every year during snowmelt. The dams slowed the flow of water and reduced erosion. It created ponds that recharged groundwater and promoted riparian and wetland vegetation. It made the soil more productive, reducing the need to divert water from other sources. And it created natural fire breaks.

Under a state analog to the Clean Water Act, a permit is required for work in perennial streams, but not ephemeral features like desert gullies. Because the Campbells’ restoration work converted the desert gullies into perennial streams and ponds, they were fined for doing the work without a permit. And their future use of the property is subject to regulation and permitting.

Restoration work like that undertaken by the Johnsons and the Campbells is not easy or cheap. Penalizing it is likely to substantially discourage others from undertaking similar efforts. And uncertain standards like the significant nexus approach can be especially discouraging, as rational landowners will avoid taking a chance that their restoration efforts will be penalized by regulation that reduces the value of their property and hamstrings their future use of it.

Liability or Asset?

While the Clean Water Act makes wetlands a liability for landowners, this needn’t be so. Wetlands provide numerous benefits which, under the right policy, could make them an asset to landowners who conserve or restore them. Wetlands rival the biological productivity of rainforests and coral reefs, producing 31 percent of the nation’s plant species. They provide habitat for wildlife and waterfowl, including a third of the species listed under the Endangered Species Act. And they store and filter water, serving a critical function for flood control and water quality.

All of these benefits are potential sources of value for landowners who conserve and restore wetlands. Some landowners, like the Johnsons and Campbells, will do so because they personally value the environmental benefits they create. Markets, however, can encourage more landowners to pursue similar work.

For instance, New York City lies at the end of a 2,000-square-mile watershed that provides clean drinking water to 8 million people. Conserving and restoring upstream wetlands can significantly improve downstream water quality and lower the city’s treatment costs. Between 1996 and 2009, the city purchased or acquired conservation easements covering 143,212 acres of wetlands. It has also provided incentive payments to upstream farmers and forest owners to conserve wetlands, restore stream buffers, and limit pollution from stormwater and agricultural runoff, with agreements reached with 95 percent of commercial farms in the watershed. These programs make wetlands a source of value for upstream landowners rather than a toehold for regulation and conflict.

Similar incentives could be developed to mitigate other types of pollution and water quality concerns. Under the Clean Water Act, the EPA can allow polluters to offset their impacts by paying to conserve and restore wetlands that filter a similar amount of pollution. In this way, landowners who have wetlands would be rewarded, rather than penalized through regulation. This is a superior approach because it puts the cost on polluters rather than interfering with the property rights of the owners of wetlands that boost water quality. It also would allow markets to steer resources to the most valuable wetlands that can be conserved and restored in a cost effective way.

All of these benefits are potential sources of value for landowners who conserve and restore welands. Some landowners will do so because they personally value the environmental benefits they create. Markets, however, can encourage more landowners to pursue similar work.

Markets can also empower conservation groups to protect wetlands. Ducks Unlimited, for instance, has worked with landowners in Montana, Wyoming, and the Dakotas to conserve prairie potholes, a type of small, shallow wetland that collects rainwater and snowmelt. Due to their remoteness, potholes are unlikely to be covered by the Clean Water Act. The group is motivated to conserve these features because they provide critical nesting habitat for ducks and other waterfowl valued by hunters, birders, and other conservationists. Through land purchases, conservation easements, and financial incentives for landowners to adopt duck- and wetland-friendly practices, the group conserved 500,000 acres of these “duck factories” between 2012 and 2017.

If federal regulation were clearer, utilities, regulated entities, and conservation groups would have greater certainty where similar market approaches are needed and would be most impactful. And, importantly, they will be motivated to make these investments based on the value that different wetlands provide. This would be a significant improvement over the inconsistent and haphazard regulation under the Clean Water Act on display in the Sacketts’ case before the Supreme Court today.