Introduction

For millennia, Indigenous communities managed forests in the American West with fire to produce a range of environmental and cultural benefits.1See Jonathan W. Long, Frank K. Lake, Ron W. Goode, The Importance of Indigenous Cultural Burning in Forested Regions of the Pacific West, 500 Forest Ecology and Mgmt. 119597 (2021), https://www.fs.usda.gov/psw/publications/jwlong/psw_ 2021_long003.pdf. This long history of cultural burning combined with frequent lightning produced fire-adapted forests, woodlands, and savannas.2See R.K. Hagmann et al., Evidence for Widespread Changes in the Structure, Composition, and Fire Regimes of Western North American Forests, 31 Ecological Applications e02431 (2021), https://esajournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1002/ eap.2431. 2 For more than a century, however, the federal government and states pursued an aggressive policy of fire suppression that effectively removed fire from the landscape.3See Holly Fretwell & Jonathan Wood, Fix America’s Forests: Reforms to Restore National Forests and Tackle the Wildfire Crisis, PERC Public Lands Report (2021), https://www.perc.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/fix-americas-forests- restore-national-forests-tackle-wildfire-crisis.pdf. While this policy has mostly been abandoned,4See Alison Berry, Forest Policy Up in Smoke: Fire Suppression in the United States, PERC (2007). See also U.S. Forest Service, Sustainability and Wildlands Fire: The Origins of Forest Service Wildland its effects linger in the form of overgrown forests, policy barriers, and cultural obstacles to restoring beneficial low-intensity fires at the scale needed to improve forest resilience and reduce wildfire risks.

The growing wildfire crisis makes this need to restore “good fire” all the more urgent. Frequent, low intensity fires are essential for bolstering forest health, maintaining wildlife habitat, and reducing smoke and other air pollutants. Today’s catastrophic “megafires,” however, scorch forests, degrade water quality, decimate habitat, and choke the air with smoke. Since 2005, the United States has three times eclipsed 10 million acres burned by wildfires in a year—an unfathomable total just a few decades ago—with the vast majority of that acreage concentrated in the West.5Nat’l Interagency Fire Ctr., Total Wildfires and Acres (2022), https://www.nifc.gov/sites/default/files/document-media/ TotalFires.pdf.

Modern wildfires are not only burning larger areas but are also more harmful for people, forests, 6See Alison Berry, Forest Policy Up in Smoke: Fire Suppression in the United States, PERC (2007), https://www.perc.org/ wp-content/uploads/2007/09/Forest_Policy_Up_in_Smoke.pdf. See also U.S. Forest Service, Sustainability and Wildlands Fire: The Origins of Forest Service Wildland Fire Research (2017), https://www.fs.usda.gov/sites/default/files/ fs_media/fs_document/sustainability-wildlandfire-508.pdf. and the environment. Nearly 100,000 structures have burned in wildfires since 2005, with two-thirds of that destruction occurring since 2017.7Headwaters Econ., Wildfires Destroy Thousands of Structures Each Year, https://headwaterseconomics.org/natural-hazards/ structures-destroyed-by-wildfire/ (Aug. 2022 update). Wildfires have killed between 13 and 19 percent of the world’s remaining giant sequoias in the past few years.8Vimal Patel, Wildfires in California Killed Thousands of Giant Sequoias, N.Y. Times (Nov. 20, 2021), https://www. nytimes.com/2021/11/20/us/california-fires-killed-sequoias.html. And they have released massive quantities of harmful air pollutants, including 112 million tons of carbon dioxide in California alone during 2020—the equivalent of adding 25 million cars to the state’s roads.9Cal. Air Resources Bd., Draft Report: Greenhouse Gas Emissions of Contemporary Wildfire, Prescribed Fire, and Forest Management Activities (Dec. 2020), https://ww3.arb.ca.gov/cc/inventory/pubs/ca_ghg_wildfire_forestmanagement.pdf.

As with any large, complex phenomenon, no single factor explains the growing wildfire crisis. Past management decisions led to a dangerous accumulation of dead and diseased trees, small trees and shrubs, and other fuels.10See Fretwell & Wood, Fix America’s Forests, supra n.3. A changing climate has lengthened the wildfire season, the period of the year in which dry and hot conditions make it more likely a fire will ignite and spread.11Deb Schweizer, Wildfires in All Seasons?, USDA blog (July 29, 2021), https://www.usda.gov/media/blog/2019/06/27/ wildfires-all-seasons. And development in the wild land urban interface, the place where human development and wild areas meet, has increased the potential for human-caused ignitions.12Volker C. Radeloff et al., Rapid Growth of the US Wildland-Urban Interface Raises Wildfire Risk, Proceedings of the Nat’l Academy of Sciences (2018), https://www.fs.fed.us/nrs/pubs/jrnl/2018/nrs_2018_radeloff_001.pdf.

The critical question is what’s to be done to tackle the wildfire crisis. Some of these factors require longterm policy and economic changes that will take decades to affect fire regimes. But as recent wildfires have shown, other factors can be addressed now, producing immediate benefits. One such factor is the use of prescribed fire, in which low-intensity fire is carefully applied to a landscape under controlled conditions to improve forest resilience, reduce extreme wildfire risks, and achieve other land-management objectives. Time and again, when wildfires have spread to areas where cultural burning practices have been restored or that have otherwise been intentionally managed with prescribed fire to increase resilience, those fires have become less destructive and easier to fight.13See USDA Climate Hubs, Prescribed Fire in the Northwest, https://www.climatehubs.usda.gov/index.php/hubs/ northwest/topic/prescribed-fire-northwest (last visited Oct. 10, 2022).

The benefits of prescribed fire were evident in Oregon’s Bootleg Fire, which burned more than 400,000 acres in 2021. In the wake of the fire, the landscape revealed huge differences between areas that had been unmanaged, mechanically thinned, or both mechanically thinned and managed with prescribed fire, with the latter producing the most resiliency. (Because of the unnatural buildup of fuels, prescribed fire often cannot be applied unless western forests are first thinned to produce safe conditions.) The benefits of prescribed fire could also be seen in real time. When the Bootleg Fire moved from the Fremont-Winema National Forest to The Nature Conservancy’s privately owned Sycan Marsh Preserve that had been thinned and burned, the fire’s behavior changed dramatically.14See Henry Fountain, This Vast Wildfire Lab Is Helping Foresters Prepare for a Hotter Planet, N.Y. Times (Jan. 5, 2022), https://www.nytimes.com/2022/01/05/climate/fire-forest-management-bootleg-oregon.html. Katie Sauerbrey, a fire manager with The Nature Conservancy, described the fire as producing 200-foot flames on neighboring federal lands. But when it crossed onto the conservation group’s private land, it went from “the most extreme fire behavior” that she “had ever seen” to a lower-intensity surface fire that spared the forest and could be fought effectively.15See id.

Much of the wildfire debate understandably focuses on the role of national forests, which make up a majority of forested acres in many western states. But expanding the use of prescribed fire on state, private, and tribal land would have significant benefits for forest resilience, community protection, and environmental conservation. In western states, non-federal lands make up between 4 percent (Nevada) 16James Menlove et al., Nevada’s Forest Resources: 2004-2013, U.S. Forest Serv. Rocky Mountain Research Station Resource Bulletin RMRS-RB-22 (2016), https://www.fs.usda.gov/rm/pubs_series/rmrs/rb/rmrs_rb022.pdf. and 56 percent (Washington)17See Wash. Forest Prot. Ass’n, Diversity of Forestland Ownership, https://bit.ly/3VkdAiL (last visited Oct. 10, 2022). of forested acres, with an average of roughly 45 percent. Importantly, private lands are often located between the wildland-urban interface and more remote public lands, or within the matrix of remote fire-prone wildlands.

State policymakers and private land managers may be able to ramp up use of prescribed fire more quickly than the federal government,18See Eric Edwards & Sara Sutherland, Does Environmental Review Worsen the Wildfire Crisis?, PERC Policy Brief (2022), https://www.perc.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/PERC-PolicyBrief-NEPA-Web.pdf (finding that the time between when the U.S. Forest Service proposes a prescribed fire to when it implements the burn varies from an average of 3.6 years when a project is categorically excluded from review under the National Environmental Policy Act to an average of 9.4 years for projects that undergo the most rigorous level of NEPA analysis and are litigated). especially considering recent controversies over the U.S. Forest Service’s use of prescribed fire.19See Mike Baker, Prescribed Burns Are Encouraged. Why Was a Federal Employee Arrested for One?, N.Y. Times (Oct. 28, 2022), https://www.nytimes.com/2022/10/28/us/oregon-prescribed-burn-boss-arrested.html; Simon Romero, How New Mexico’s Largest Wildfire Set Off a Drinking Water Crisis, N.Y. Times (Sept. 26, 2022), https://www.nytimes.com/2022/ 09/26/us/new-mexico-las-vegas-fire-water.html. And as the experience in Sycan Marsh demonstrates, even pockets of well managed areas within larger forested landscapes can make a difference in mitigating the consequences of wildfire. By producing areas that are more resilient to fire, private lands can also conserve wildlife habitat, water quality, and other ecosystem services. For these reasons, several states have identified making it easier for private landowners to use prescribed fire as a critical step in tackling the wildfire crisis.20See, e.g., Cal. Wildfire and Forest Resilience Task Force, California’s Strategic Plan for Expanding the Use of Beneficial Fire (2022), https://www.fire.ca.gov/media/xcqjpjmc/californias-strategic-plan-for-expanding-the-use-of-beneficial-fire-march- 16_2022.pdf.

Prescribed Fire Use

Prescribed fire, also referred to as prescribed burning or controlled burning, is the intentional and planned application of fire to achieve land-management objectives, such as reduced wildfire risk, improved forest health, or enhanced wildlife habitat. These fires are ignited under controlled conditions, including temperature, humidity, and wind speed, to reduce the risk of an escape and manage smoke.

There are several types of prescribed fires. In a broadcast burn, a crew constructs firebreaks to keep the fire from spreading outside the planned area, uses drip torches or helicopters to ignite ground-level fuels, and monitors the fire to make sure it does not increase in intensity or escape containment. In a pile burn, fuels are gathered and burned in a selected location surrounded by a firebreak.

Landowners may implement small, simple prescribed fires with the help of family or neighbors. For more complex burns, landowners may seek out the help of an experienced “burn boss,” an entrepreneur who plans, organizes, and supervises prescribed burns.

Landowners should have good incentives to restore “good fire” to western forests. Prescribed fire not only benefits their land but can also be a more cost-effective management tool than mechanical thinning and other methods.21See Lenya Quinn-Davidson & Jeffery Stackhouse, Burning by the Day: Why Cost/Acre is Not a Good Metric for Prescribed Fire, Cal. Native Grasslands Ass’n (2019), https://cnga.org/resources/Documents/Resources/Wildfire%20Resources/ Burn%20Cost_Quinn-Davison,%20Stackhouse_Summer%202019-3.pdf. Prescribed fires also produce numerous benefits for surrounding land-owners and communities, although landowners may receive no reward for producing these benefits. Surveys suggest that, for these and other reasons, landowners are interested in ramping up prescribed fire.22See Lenya Quinn-Davidson & J. Morgan Varner, Impediments to Prescribed Fire Across Agency, Landscape and Manager: An Example from Northern California, 21 Int’l J. of Wildland Fire 210 (2018) (reporting survey of Northern California landowners and land-managers that found 66 percent of respondents wished to increase their use of prescribed fire but were prevented from doing so by regulatory obstacles, limited capacity, and local conditions).

Despite these benefits, there’s limited use of prescribed fire in the West and little public data available about what burning does take place.23See Coal. of Prescribed Fire Councils, 2020 Prescribed Fire Use Report 4, 6 (2020), https://www.prescribedfire.net/pdf/2020-Prescribed-Fire-Use-Report.pdf (reporting that no western state burns more than 50,000 acres across all lands but not providing granular data). The lack of the practice has deprived the West of a culture of burning among landowners and communities—especially compared to the Southeast, which maintained the practice through the 20th century and is currently responsible for 70 percent of the nation’s prescribed burning. 24See Crystal A. Kolden, We’re Not Doing Enough Prescribed Fire in the Western United States to Mitigate Wildfire Risk, 2 Fire 30 (2019), https://www.mdpi.com/2571-6255/2/2/30. Many landowners lack the experience and resources needed to be comfortable embracing the tool. And there are too few expert practitioners available to plan, organize, and supervise the most complex burns, which both limits the number of ambitious burns and drives up their costs.

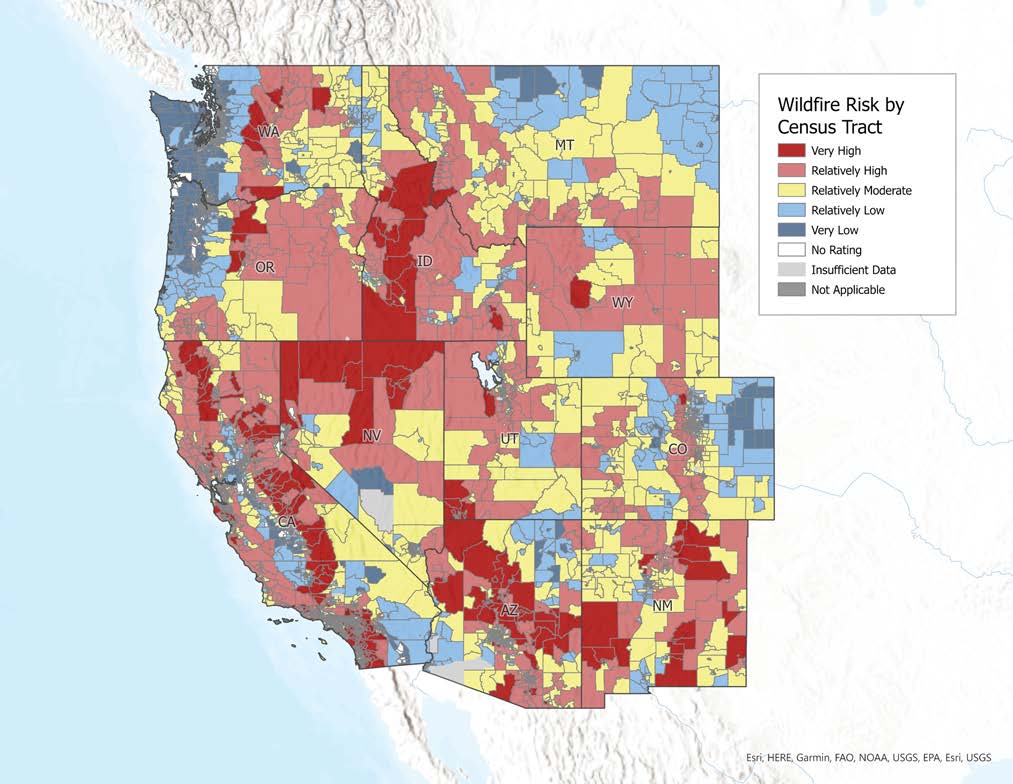

Figure 1:

Map of the Wildfire Risk in Western States

State policies, many of them holdovers from the era of aggressive fire suppression, can further discourage use of prescribed fire. Landowners must invest time and resources in understanding a state’s permitting process and applying for permits. The limited number and unpredictability of “burn days” in which states allow burning can make it difficult for landowners to plan and implement a prescribed fire. Training opportunities, including state certification programs, are limited, relative to demand. And state liability laws can make prescribed fires excessively risky compared to other, less ecologically effective management practices. Reforms to reduce these obstacles and provide better incentives for landowners are needed to expand the use of prescribed fire, improve forest health, and tame the wildfire crisis.

This report is a collaboration between the Property and Environment Research Center, the national leader in creating market solutions for conservation, and Tall Timbers, an internationally recognized organization with over 60 years of experience using prescribed fire science to solve land management problems. Informed by a workshop featuring leading prescribed fire experts from across the West, this report is the most comprehensive analysis of prescribed fire policy in the 25Volker C. Radeloff et al., Rapid Growth of the US Wildland-Urban Interface Raises Wildfire Risk, Proceedings of the Nat’l Academy of Sciences (2018), https://www.fs.fed.us/nrs/pubs/jrnl/2018/nrs_2018_radeloff_001.pdf. western states, with a focus on state-level policies affecting the use of prescribed fire on private lands. It analyzes in detail the most significant obstacles to prescribed fire in the West, describes western states’ recent progress on these fronts, and proposes reforms that could unleash private landowners and entrepreneurs to scale up prescribed fire. Below is a summary of the report’s key topics and recommendations. Each topic is analyzed in more detail in the sections that follow with more detailed recommendations for how these reforms could be implemented.

Recommendations

- Improve permitting systems to remove bureaucratic obstacles to prescribed burning.

- Develop more flexible approaches to setting “burn days” in which different types of prescribed fires can be implemented.

- Design training opportunities and other resources to educate and support, rather than regulate, landowners’ use of prescribed fire.

- Clarify and improve liability regimes to reflect the public benefits of prescribed fire.

- Harness private investment to benefit forest health through catastrophe bonds.

1. Permitting Systems

Improve Permitting Systems to Encourage Private Burning

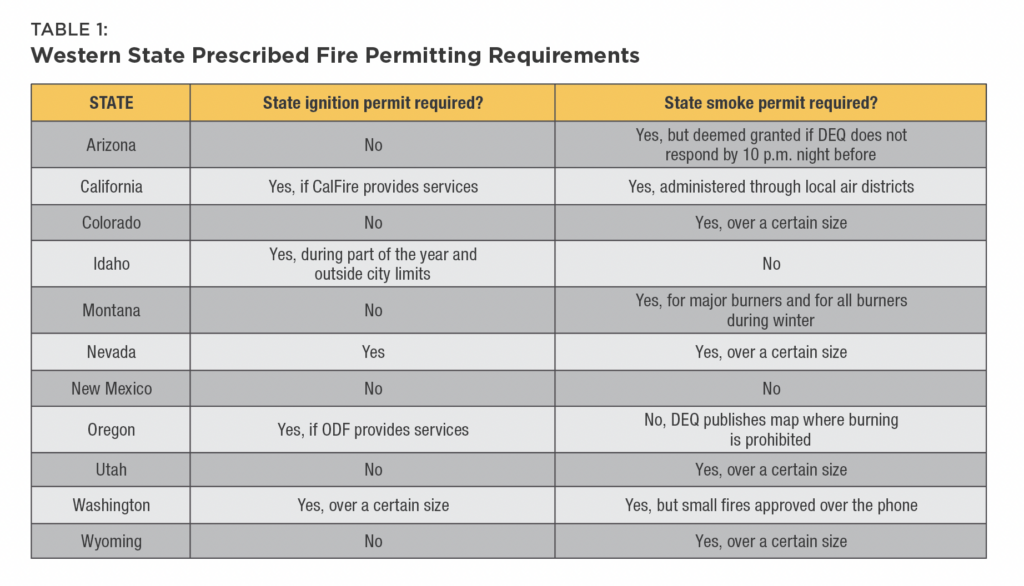

Western states may require permits for some or all uses of prescribed fire by private landowners, with requirements varying significantly among states. 26While this report focuses on prescribed burning on private land, surveys of federal agency personnel have found that they face similar obstacles, although permitting and other requirements on federal land are generally set by federal rather than state law. See Courtney Schultz et al., Prescribed Fire Policy Barriers and Opportunities: A Diversity of Challenges and Strategies Across the West, Univ. of Oregon 8–9 (2018), https://ewp.uoregon.edu/sites/ewp.uoregon.edu/files/WP_86.pdf (survey of BLM and Forest Service prescribed burners); Courtney Schultz et al., Policy Barriers to Implementing Prescribed Fire, Colo. State Univ. Pub. Lands Pol’y Gp. Briefing Paper (2017), https://www.firescience.gov/projects/16-1-02-8/ project/16-1-02-8_Policy-Barriers-to-Prescribed-Fire-BP-Updated.pdf (same). These permit requirements can serve several functions: notification to agencies that may be called upon to provide suppression assistance, external review of a plan’s adequacy for safety and consistency with air quality regulations, and reassurance to a public that may be wary of prescribed fire. But they may also introduce costs, bureaucracy, delay, and uncertainty that discourage landowners from using prescribed fire.27See Sara A. Clark, Andrew Miller, & Don L. Hankins, Good Fires: Current Barriers to the Expansion of Cultural Burning and Prescribed Fire in California and Recommended Solutions, Karuk Tribe (2021), https://karuktribeclimatechange- projects.files.wordpress.com/2022/06/karuk-prescribed-fire-rpt_2022_v2-1.pdf; Robert A. York et al., Burn Permits Need to Facilitate—Not Prevent—“Good Fire” in California, 74 Cal. Ag. 62 (2020), https://ucanr.edu/sites/CentralSierra- LivingwithFire/files/329508.pdf. But see Morgan Russell et al., Legal Barriers to Prescribed Burning, Texas A&M AgriLife Extension Rep. (2016), https://agrilife.org/rxburn/files/2017/09/Legal-Barriers-to-Prescribed-Burning-ERM-022.pdf (finding that permit requirements may encourage landowners to adopt prescribed fire by providing assurance that they won’t later be deemed to have acted negligently).

The first choices states must make are what types of permits to require and when to require them. Permit requirements are generally divided between ignition permitting, which considers the safety of a prescribed fire plan, and smoke permitting, which considers air quality impacts. These permitting requirements may be administered by different agencies or levels of government, depending on who is the primary air regulator or provider of fire-suppression services.

One option for states is to recognize a “right to burn” and forgo any formal permitting process, at least for some seasons or types of burns.28See, e.g., Wash. Dept. of Nat. Res., Burn Permits, https://www.dnr.wa.gov/programs-and-services/wildfire/outdoor- burning/burn-permits. This approach reduces burdens on both landowners and the state agency that would otherwise have to divert personnel to review applications for low-risk burns. In Wyoming, for instance, small burns (those under six acres in forests, eight acres in shrublands, and 25 acres in grasslands) at least 500 feet from any human-occupied structure require neither an ignition permit nor smoke permit from the state.29See Nick Dillinger et al., Wyoming Prescribed Burning Regulations: Review of Policy, Guidelines, and Case Law for Private Lands, U. Wyo. College of Ag. and Nat. Res. Extension Rep. (2020), https://wyoextension.org/publications/html/ B1354/; John Derek Scasta et al., Burning Irrigation Ditches, U. Wyo. College of Ag. & Nat. Res. Extension Rep. 13 (2019), https://www.lglpwyoming.org/vertical/sites/%7BFA6BF46D-42F2-425B-A2D5-9C28F7E2121E%7D/uploads/Irrigation_Ditch_Burning_Guidelines.pdf. See also 10 Wyo. Admin. Rules § 2. Montana similarly limits state permitting to “major burners,” those who burn more than 5,000 acres per year, or burning during winter, when inversions can sharply increase the impacts of smoke on local air quality.30See Montana Dept. of Enviro. Quality, Open Burning, https://deq.mt.gov/air/Programs/burning. Many Montana counties have also established seasons in which no local permit is required.31See Fire Safe Kalispell, Need a Burning Permit?, https://www.firesafekalispell.com/.

New Mexico takes the strongest “right to burn” approach, requiring neither an ignition permit nor smoke permit at the state level.32See Working Group Report to the New Mexico Legislature, Expanding the Use of Prescribed Fire in New Mexico (2020), https://nmrxfire.nmsu.edu/documents/expanding-the-use-of-prescribed-fire-in-new-mexico—june-2020.pdf. The lack of a permitting requirement is not the only way in which New Mexico is unique among western states. It also imposes double liability on anyone whose prescribed fire escapes. See id. Indeed, the state recently limited local governments’ permitting authority, under a 2021 law that directs a state agency to develop a model permit local governments may use.33See Prescribed Burning Act, H. B. 57 § 5 (2021). Unless they adopt this model permit, local governments are forbidden from having a permit requirement.34See id. § 6.

Most state-level permitting in the West concerns smoke and its effect on local air quality. The complexity of this permitting varies according to state regulation, the number of emissions sources in an airshed, and other factors. In Washington, for instance, a state agency writes an individual smoke permit for each burn plan, which can now be submitted through an online portal.35See Schultz et al., Prescribed Fire Policy, supra n.1, at 9. See also Wash. Dept. of Nat. Res., Burn Portal, https://burnportal.dnr.wa.gov/. Other states, like California, establish state smoke permits but administer the program through local agencies.36See Schultz et al., Prescribed Fire Policy, supra n.1, at 8.

Relatively few western states require state permits for igniting a prescribed fire. Instead, if this permitting occurs at all, it’s done at the local level, usually through the local fire department. A few states require state ignition permits in areas where a state agency provides fire-suppression services. CalFire and the Oregon Department of Forestry, for instance, provide services to most of the forested areas in their respective states and require a permit to ignite a prescribed fire.37See CalFire, State Responsibility Areas, https://calfire-forestry.maps.arcgis.com/apps/webappviewer/index.html?id= 468717e399fa4238ad86861638765ce1; Or. Dept. of Forestry, Prescribed Forest Burning, https://www.oregon.gov/odf/fire/ pages/burn.aspx. Table 1 describes ignition and smoke permitting requirements in western states.

While these permitting programs are intended to protect air quality, reduce the risk of escapes, and serve other public purposes, they can also increase the costs of using prescribed fire for landowners. One of the most obvious costs is the fee charged to obtain the permit. Fortunately, many states distribute permits for free or a nominal fee. But others charge a much larger fee based on the cost of administering the program. In some areas of California, for instance, permits cost up to $1,400 before accounting for the landowners’ cost to prepare the burn plan and other permitting materials.38See Clark, Miller, & Hankins, Good Fires, supra n.2, at 14–15. Washington’s fee, which is based on the amount of debris burned, can exceed $10,000.39See Wash. Dept. of Nat. Res., Burning Permit Fee Schedule (2012), https://www.dnr.wa.gov/publications/rp_burn_ feesched.pdf. Large permitting fees essentially punish landowners for adopting a practice that produces both private and significant public benefits, including reduced state liability for future wildfire suppression costs.

The complexity of a permitting system can also increase the costs to landowners by requiring them to figure out multiple systems within multiple agencies or levels of government. To reduce these costs, states should consolidate requirements into a single permit administered by whichever state or local agency landowners would logically expect to require a permit. In Oregon, for instance, the Department of Environmental Quality notifies the Department of Forestry whether burning is appropriate for air quality, which the latter takes into account when issuing permits.40See Schultz et al., Prescribed Fire Policy, supra n.1, at 8. In other states, a local government, agency, or fire department may be the best choice as the lead permitting agency.

States also vary in how long it takes to obtain burn permits and how long those permits are valid. In Idaho, for instance, an ignition permit can be obtained online, is issued virtually instantaneously, and is good for 10 days.41See Idaho Dept. of Lands, State Burn Permits required May 10 – October 20 (2021), https://www.idl.idaho.gov/ pressrelease/state-burn-permits-required-may-10-october-20/#:~:text=Permits%20are%20free%20and%20good,are%20immediately%20issued%20and%20valid. In Wyoming, review of a local ignition permit takes 72 hours, but the permit is good for the year.42See Natrona County, Burn Permit Payment System, https://burnpermit.natronacounty-wy.gov/. And in Washington, the Department of Natural Resources reports that a smoke permit typically takes two weeks to obtain; however, it cautions that the personnel who process permit applications also have fire suppression duties that may cause them to stop reviewing permit requests for extended periods of time “when the fire bell rings.”43See Washington Governor’s Office of Regulatory Innovation and Assistance, Burn Permit, https://apps.oria.wa.gov/permithandbook/ permitdetail/32#:~:text=Processing%20times%20for%20individual%20burn,a%20completed%20application%20is%20received.

States should also seek to establish clear standards for when permits will be issued, the timeline for issuing permits, and what conditions will be imposed. This has already been accomplished in states that issue general permits for certain burn types or seasons. When these questions are left instead to the individual agency official reviewing a permit request, a risk-averse official may delay or unreasonably condition a permit in ways that increase the costs to burners.44See Clark, Miller, & Hankins, Good Fires, supra n.2, at 14, 17.

In Northern California, smoke rises above a community prescribed burn carried out on private land to decrease wildfire risk.

Western larch seedlings sprout following a prescribed fire in Montana.

In addition to general permitting, states have adopted several other models to reduce permitting delays and uncertainty. In Arizona, for instance, a smoke permit request is deemed approved if the Department of Environmental Quality does not respond by 10 p.m. the night before the planned burn.45See Ariz. Admin. Code § R18-2-1506. Washington requires agencies to track and publicly report how long it takes to issue any permit, including prescribed burn permits, to hold agencies accountable for unnecessary bureaucracy.46See Wash. Office of Reg. Innovation & Assistance, Permit Timeliness Report: 2015 (2015), https://www.oria.wa.gov/ Portals/_oria/VersionedDocuments/Regulatory_Improvement/ORIA-2015-PermitTimelinessProgressReport.pdf. This process, which began in 2015, revealed that the state’s Department of Environmental Quality did not track and thus did not know how long it took to issue a prescribed fire permit. After repeated proddings from the governor’s office, the department implemented an online application portal in 2020 to streamline the process and track the agency’s progress toward reducing permitting delays.47See Wash. Office of Reg. Innovation & Assistance, Permit Timeliness Report: 2020 (2020), https://www.oria.wa.gov/ Portals/_oria/VersionedDocuments/Regulatory_Improvement/ORIA-2020-PermitTimelinessProgressReport.pdf.

By increasing costs and uncertainty, complex permitting regimes discourage landowners from adopting prescribed fire as a management tool. Considering the growing interest among western states to encourage use of the practice, states should continue to look for ways to streamline and simplify the permitting process, without sacrificing safety or air quality.

Recommendation for States

- Limit permitting fees, especially where prescribed fire produces significant public benefits.

- Use right to burn laws, general permitting, and other policies to reduce procedural hoops for low-risk burns.

- Consolidate requirements for formal permits into a single permit, and designate a lead agency at the state or local level to issue the permit.

- Establish clear standards for when burn permits will be needed, the timeline for issuing permits, and the conditions permits will impose.

- Create procedures to make agencies accountable for permitting delays.

Before (top) and after (bottom) a forest restoration project in Oregon that included mowing, thinning, and prescribed burning.

© Oregon State University

2. Burn Opportunities

Expand Burn Opportunities to Promote the Use of “Good Fire”

One of the chief benefits of prescribed fire is that it can be applied when conditions are relatively good, unlike a catastrophic wildfire during peak fire season. Therefore, when to burn is an essential practical and policy question. Throughout the West, however, the period with the best conditions is shrinking as the wildfire season expands.48See Raymond Zhong, Why Climate Change Makes It Harder to Fight Fire With Fire, N.Y. Times (May 5, 2022), https:// www.nytimes.com/2022/05/05/climate/wildfires-prescribed-burn.htm. See also Janine A.Baijnath-Rodino et al., Historical Seasonal Changes in Prescribed Burn Windows in California, 836 Sci. of the Total Enviro. 155,723 (2022), https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0048969722028194. Greater flexibility regarding when prescribed fires can be conducted will make it easier to expand their use.

The timing of burning is governed by three factors: local conditions (such as humidity and wind speed), regional air quality, and the availability of fire-fighting resources.49See Randy Striplin et al., Retrospective Analysis of Burn Windows for Fire and Fuels Management: An Example From the Lake Tahoe Basin, California, USA, 16 Fire Ecology 13 (2020), https://fireecology.springeropen.com/counter/pdf/10.1186/ s42408-020-00071-3.pdf. The ideal windows to take advantage of each of these factors may not align. In some areas, for instance, local conditions and firefighting resources might favor increased burning in the winter.50See Baijnath-Rodino et al., Historical Seasonal Changes, supra n.1. But many areas of the West experience winter inversions, during which a layer of cold air gets trapped under a layer of warm air, which prevent smoke and other air pollutants from dispersing.51See Courtney Schultz et al., Prescribed Fire Policy Barriers and Opportunities: A Diversity of Challenges and Strategies Across the West, Univ. of Oregon (2018), https://ewp.uoregon.edu/sites/ewp.uoregon.edu/files/WP_86.pdf (identifying inversions as a significant limit on prescribed fire in Montana, Nevada, Utah, and Wyoming). See also Montana Dept. of Envtl. Quality, Why Can’t I Burn?: Weather, Air Quality, and Open Burning, https://deq.mt.gov/files/Air/AirQuality/ Documents/OpenBurn/WhyCantIBurn.pdf. In the arid Southwest, the optimal local conditions and air quality can be in the summer before monsoon season, but fire-fighting resources are often limited during this period because they are occupied responding to wildfires in other areas across the West.52See Schultz et al., Prescribed Fire Policy, supra n.4. (identifying resources devoted to wildland fire as a significant limit on prescribed fire in Arizona and New Mexico).

Burn windows are not merely seasonal but can open and shut from day to day. A study of burn days in California’s Tahoe basin from 1999 to 2019, for instance, found that all three factors aligned for an average of only 50 to 100 days per year.53See Striplin et al., Retrospective Analysis, supra n.2. And consecutive burn days were uncommon, with two or fewer two- to three-day burn windows per year during spring and fall.54See id. Such unpredictability can make it difficult to plan and organize resources and manpower.

Air quality restrictions on prescribed fire stem from the federal Clean Air Act, which directs states or the Environmental Protection Agency to manage emissions to meet air quality standards.55See Sara A. Clark, Andrew Miller, & Don L. Hankins, Good Fires: Current Barriers to the Expansion of Cultural Burning and Prescribed Fire in California and Recommended Solutions, Karuk Tribe (2021), https://karuktribeclimatechangeprojects.files.wordpress.com/2022/06/karuk-prescribed-fire-rpt_ 2022_v2-1.pdf Despite wildfire smoke being a recurring, major, and growing source of several harmful air pollutants, it does not count against emissions limits because federal law treats wildfires as “exceptional events.”56See Holly Fretwell & Jonathan Wood, Fix America’s Forests: Reforms to Restore National Forests and Tackle the Wildfire Crisis, PERC Public Lands Report (2021), https://www.perc.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/fix-americas-forests- restore-national-forests-tackle-wildfire-crisis.pdf. See also Marissa L. Childs et al., Daily Local-Level Estimates of Ambient Wildfire Smoke PM2.5 for the Contiguous US, 56 Envtl. Sci. Tech. 13,607 (2022), https://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/ acs.est.2c02934#; Rosana Aguilera, Wildfire Smoke Impacts Respiratory Health More Than Fine Particles From Other Sources: Observational Evidence from Southern California, 12 Nature Comms. 1493 (2021), https://www.nature.com/articles/ s41467-021-21708-0; Jes Burns & Maya Miller, Change To Oregon Smoke Rules Seeing Early Results For Prescribed Burns, Or. Pub. Broadcasting (June 19, 2019), https://www.opb.org/news/article/oregon-smoke-rules-prescribed-fires-wildfire-air- quality/ (reporting that 93 percent of Oregon’s unhealthy air quality days in 2018 were due to wildfire smoke). Smoke from prescribed fires, by contrast, is treated less favorably than wildfire smoke and must be accounted for under air quality standards, even though Indigenous burning was integral to the ecological function and fire-hazard reduction of western wildlands.57See Fretwell & Wood, Fix America’s Forests, supra n.9; Clark, Miller, & Hankins, Good Fires, supra n.8. Thus, air quality standards can prevent prescribed fire use during periods when smoke dispersal is limited, there are other significant sources of pollution, or wildfire smoke from neighboring states has already degraded the air.58See Clark, Miller, & Hankins, Good Fires, supra n.8; Schultz et al., Prescribed Fire Policy, supra n.4 (survey of federal land managers identifying air quality standards as a primary barrier in every state except Washington and New Mexico).

States, of course, cannot change federal requirements. But there are several steps they can take to reduce air quality-related obstacles to prescribed fire. Washington and Oregon impose stricter air quality standards on prescribed fire than required by federal law, prohibiting any smoke intrusion into populated areas.59See Schultz et al., Prescribed Fire Policy, supra n.4, at 10. While avoiding these impacts is a laudable goal, applying this rule in the prescribed fire context ignores the worse air quality impacts if an area instead burns in a catastrophic wildfire.60See Brittany West et al., Amending Oregon’s Air Quality Rules to Allow More Prescribed Fire, Oregon State Univ. Natural Resource Policy Brief (June 2, 2020), https://blogs.oregonstate.edu/brittanywest/2020/06/02/amending-oregons-air- quality-rules-to-allow-more-prescribed-fire/. To expand opportunities for prescribed fire, these states should apply federal air quality standards to prescribed fire rather than a more stringent standard.61See id.

Other states should consider whether the criteria they use to measure air quality unnecessarily penalize prescribed fire. In 2008, for instance, California’s Air Resources Board altered its criteria from one that focused on the presence of high-pressure systems (which are generally associated with hot, dry conditions) to one that gave greater weight to the atmosphere’s capacity to disperse smoke.62See Striplin et al., Retrospective Analysis, supra n.2, at 12. This small, technical change in how the state assessed air quality meaningfully increased the number of burn days available to prescribed burners.63See id. Other states should evaluate the metrics they use for similar opportunities to increase the number and predictability of burn days.

Because states rather than the federal government determine whether wind, humidity, and other local conditions are appropriate for prescribed fire, they have more flexibility in taking these factors into account when setting burn windows. These conditions affect the likelihood that a prescribed fire will grow more intense than intended or escape containment. Based on these factors, states or local governments declare seasonal or daily burn windows.64See, e.g., Cal. Fire, Current Burn Status, https://burnpermit.fire.ca.gov/current-burn-status/. In some states, this is a binary choice: burning is either allowed or suspended. 65See id. In others, there’s a third choice: “marginal” days during which a limited amount of burning is allowed on a case-by-case basis.66See Montana Dept. of Envtl. Quality, Open Burning, https://deq.mt.gov/air/Programs/burning (allowing prescribed fire on a case-by-case basis during winter).

A winter pile burn in Arizona

To encourage more use of prescribed fire and reduce uncertainty, states should adopt more gradual approaches to determining burn days to better reflect the gradual changes in risk as conditions change. States should expand the “marginal” day concept to set burn days for different types of burns based on prevailing conditions. In good conditions, all types of burns could be authorized. But as conditions depart from ideal, rather than prohibiting burning entirely, a state could allow smaller and less complex burns. Spreading out burning in this way could have other ancillary benefits, like making better use of limited manpower and prescribed fire resources.

Perhaps because the West does not have a strong culture of prescribed fire and recent history of its use, there is some evidence that landowners underuse opportunities to burn because they do not know of them. A recent study suggests, for instance, that winter can be an effective time to apply prescribed fire in the Sierra Nevada, especially during periods of drought where snowpack is less of a constraint.67See Robert A. York et al., Opportunities for Winter Prescribed Burning in Mixed Conifer Plantations of the Sierra Nevada, 13 Fire Ecology 33 (2021), https://fireecology.springeropen.com/articles/10.1186/s42408-021-00120-5. The risk of escape is minimal during this time.68See id. And more resources to implement a burn or contain an escape are potentially available since there is less competition from regional wildfire suppression. These windows have been underused, even as burning during peak seasons of spring and fall have been constrained by drought, wildfires, and other factors.69See id. States that have historical records of air quality and local conditions aligning to allow for burning should publicize previously overlooked opportunities, highlighting the potential cost-savings, reduced bureaucracy, and other benefits available for landowners who seize them.

One challenge to planning and executing prescribed burns is the need to manage smoke emitted from them. © Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife

Finally, states should announce burn days as early as possible to give landowners time to arrange burns. States vary considerably in when they make these announcements. Colorado does not announce burn days until 9 a.m. the day of, effectively requiring landowners and contract burners to make preparations with no certainty whether burning will be allowed.70See Colorado Dept. of Public Health & Enviro., Colorado Open Burning Forecast, https://www.colorado.gov/airquality/ burn_forecast.aspx. California’s Air Resources Board announces whether air quality is sufficient to allow burning by 3 p.m. the day before, giving some time to make arrangements after learning that a burn can go forward.71See Cal. Air Resources Bd., Prescribed Burning, https://ww2.arb.ca.gov/our-work/programs/prescribed-burning.

The Montana-Idaho Airshed Group, a collaboration between state agencies and the timber industry, forecasts conditions for smoke dispersion a week ahead18 of time and updates them daily.72See Montana-Idaho Airshed Group, Airshed Management System, https://mi.airshedgroup.org/. Although smoke dispersion models are improving, forecasting is not an exact science, and air quality, wind conditions, and other factors can change. But to the extent practicable, states should try to publicize when burning will be allowed as far in advance as possible to allow burners to make arrangements with more confidence. Increasing certainty will enable decisions that prioritize lands based on potential benefit rather than on smaller, and often less impactful sites.

Recommendation for States

- Limit permitting fees, especially where prescribed fire produces significant public benefits.

- Use right to burn laws, general permitting, and other policies to reduce procedural hoops for low-risk burns.

- Consolidate requirements for formal permits into a single permit, and designate a lead agency at the state or local level to issue the permit.

- Establish clear standards for when burn permits will be needed, the timeline for issuing permits, and the conditions permits will impose.

- Create procedures to make agencies accountable for permitting delays.

3. Fire Resources

Unleash Prescribed Fire Resources for Landowners

Because prescribed fire has long been absent from western landscapes, many private landowners are unfamiliar with the method and lack the resources needed to safely implement burns. Making more resources, training, and experiential opportunities available to landowners, entrepreneurs, and other would-be burners is essential to expanding the use of prescribed fire.

While prescribed fire can be safely applied without complicated or expensive equipment, there are still some significant upfront costs required to start burning. In 2019, experts from the University of California Cooperative Extension estimated the cost to put together a “burn trailer” containing necessary and useful equipment for a prescribed fire.73See Lenya Quinn-Davidson & Jeffery Stackhouse, Field Report: Building a Burn Trailer to Support Your Community’s Prescribed Fire Efforts, Univ. of Cal. Coop. Extension Grasslands (2019), https://ucanr.edu/sites/forestry/files/ 312932.pdf. Excluding the items the experts identified as lower priority, the cost was $43,000.74See id. An individual landowner executing only a small burn might be able to avoid some of this expense, but she would still need to make a fivefigure investment to get started.

Because land is burned only intermittently, it makes more sense for landowners to coordinate and share resources or for entrepreneurs to provide this service. Prescribed burn associations have proven to be an effective way to provide this coordination and resource-sharing.75See id. (reporting that prescribed burn associations are seen “as the only realistic model for bringing fire back to private lands at a meaningful scale”); John. R. Weir, Prescribed Burning Associations: Landowners Effectively Applying Fire to the Land in Proceedings of the 24th Tall Timbers Fire Ecology Conference: The Future of Prescribed Fire: Public Awareness, Health, and Safety (2010), https://talltimbers.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/44- Weir2010_op.pdf. See also John Diaz, Jennifer E. Fawcett, & John R. Weir, The Value of Forming a Prescribed Burn Association, Southern Fire Exchange Fact Sheet (2016), https://ucanr.edu/sites/Mariposa/files/321638.pdf. These voluntary, grassroots organizations make it easier for landowners to adopt prescribed fire as a management tool by pooling resources, providing training, coordinating burns across property lines, and organizing crews to implement burns.76See Diaz, Fawcett, & Weir, The Value of Forming a Prescribed Burn Association, supra n.3. See also David Toledo et al., The Role of Prescribed Burn Associations in the Application of Prescribed Fires in Rangeland Ecosystems, 134 J. of Envtl. Mgmt. 323 (2014), http://sonora.tamu.edu/files/2015/12/The-role-of-prescribed-burn-associations-in-the-application-of-prescribed-fires-in-rangeland-ecosystems.pdf (finding that prescribed burn associations cause landowners to feel more comfortable with prescribed fire and less concerned with liability risks). They also provide a way for those who benefit from prescribed fire to support its use. The Humboldt County Prescribed Burn Association in California, for instance, purchased its burn trailer through contributions from the California Deer Association, which values the habitat that prescribed fire creates and maintains.77See Quinn-Davidson & Stackhouse, Field Report, supra n.1.

Elk and other wildlife benefit from abundant green forage that appears after prescribed burns,such as in this Oregon forest. © Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife

While there are more than 100 prescribed burn associations nationwide, they are relatively new to the West. California is the only western state to have more than one, with spread across Northern California, the Central Coast, and San Diego.78See California PBA, California’s Prescribed Burn Associations, https://calpba.org/connect-ca-pba; Great Plains Fire Science Exchange, Prescribed Burn Associations, https://gpfirescience.org/prescribed-burn-associations/. See also https://CalPBA.org (website providing advice on how to set up a prescribed burn association, contact for existing associations in the state, and training resources that associations can use). Outside of California, three prescribed burn associations cover portions of Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico, and Oregon.79See Great Plains Fire Science Exchange, supra n.6. And the Ember Alliance is working to expand prescribed burn associations in Colorado, focusing on opportunities for pile burning.80See The Ember Alliance, Colorado Prescribed Burn Associations, https://emberalliance.org/cpba/#:~:text=Prescribed%20 Burn%20Associations%20(PBAs)%20are,health%20management%20and%20wildfire%20mitigation.

Even with access to needed tools, many landowners and entrepreneurs would need training and practice to feel comfortable applying fire to their land. To provide this training, several western states have developed government-administered certified burner (or “burn boss”) programs that teach how to plan, execute, and supervise prescribed burns of various complexities.81See Forest Guilds Steward, Insights and Suggestions for Certified Prescribed Burn Manager Programs 5 (2020), https:// foreststewardsguild.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/InsightsRecommendationsCPMBprograms.pdf. In the West, less than half of states have these programs, and most are in their infancy.

Government-run certification programs involve a mix of education and regulation. The primary incentives for would-be burners to participate are regulatory. State rules may require certification to plan and supervise certain types of burns. Certified burners may enjoy a reduced risk of liability. (See p. 26.) And they may be exempt from some burn bans and other restrictions.82See id. at 12, 27. See also Lenya Quinn-Davidson, Finding the Sweet Spot: Rigor Versus Impact in Certified Burner Programs, Fire Adapted Communities Learning Network (2019), https://fireadaptednetwork.org/finding-the-sweet-spot- rigor-versus-impact-in-certified-burner-programs/. Tasking a state agency with developing a program that is both educational and regulatory can make it difficult to strike a balance between achievable and rigorous standards; the former will encourage landowners to participate, but the latter will make communities more accepting of prescribed fire.83See Forest Guilds Steward, Insights and Suggestions, supra n.9,. at 25. See also Quinn-Davidson, Finding the Sweet Spot, supra n.10. Table 2 summarizes various aspects of western states’ certification programs and private prescribed fire associations.

Existing certification programs charge relatively low fees compared to the costs of developing and implementing them, which can cause them to be a tax on the resources of an already strained agency responsible for implementing one.84See Forest Guilds Steward, Insights and Suggestions, supra n.9, at 25–26. Cf. Courtney Schultz et al., Strategies for Increasing Prescribed Fire Application on Federal Lands: Lessons from Case Studies in the U.S. West, Public Lands Policy Group Practitioner Paper Number 6 (2020), https://ewp.uoregon.edu/sites/ewp.uoregon.edu/files/WP_99.pdf (reporting that limited agency resources and lack of support from agency leadership are two of the primary obstacles to increasing the use of prescribed in the West). Furthermore, an agency could face criticism if a certified burner is responsible for an escaped fire. For these reasons, agencies may be overly risk averse in implementing programs and certifying burners.85See Sara A. Clark, Andrew Miller, and Don L. Hankins, Good Fires: Current Barriers to the Expansion of Cultural Burning and Prescribed Fire in California and Recommended Solutions, Karuk Tribe (2021), https:// karuktribeclimatechangeprojects.files.wordpress.com/2022/06/karuk-prescribed-fire-rpt_2022_v2-1.pdf (reporting that agency culture, including at state agencies, is a significant obstacle to increased use of prescribed fire). See also Lynn A. McGuire & Elizabeth A. Albright, Can Behavioral Decision Theory Explain Risk-Averse Fire Management Decisions?, 211 Forest Ecology & Mgmt. 47 (2005), https://trainingcenter.fws.gov/courses/ALC/ALC3159/resources/Maguire_and_Albright_ 2005.pdf (discussing the role of irrational risk aversion in keeping federal land management agencies from meeting prescribed fire goals). Unless an agency’s leadership is strongly committed to the program’s success and willing to prioritize resources for it, it may fail to achieve the state’s goals due to lack of promotion, infrequent trainings, and bureaucratic delays —as have limited several western states’ programs.86See Lenya Quinn-Davidson, California Burn Boss Program: New Path Forward or Dead-End Street?, Fire Adapted Communities Learning Network (2022), https://fireadaptednetwork.org/california-burn-boss-program-new-path-forward- or-dead-end-street/ (reporting that California had not certified anyone eight months after the state’s first class of extremely experienced prescribed fire practitioners completed the course); Colo. Div. of Fire Prevention & Control, Colorado Certified Burn Program, https://dfpc.colorado.gov/certifiedburnprogram (showing that only two trainings were offered in 2022 and none are yet scheduled for 2023). See also Forest Guilds Steward, Insights and Suggestions, supra n.9, at 25–26.

Prescribed Fire Councils

All western states except Arizona and Montana have established prescribed fire councils, which bring together federal and state agencies, nongovernmental organizations, and tribal and private interests.87See Coal. of Prescribed Fire Councils, About Our Coalition, https://www.prescribedfire.net/index.php/about-us. Depending on the challenges to implementing prescribed fire in a state, a council may be focused on sharing information, techniques, and experiences, or it may seek to foster dialogue between regulators, the regulated, and interest groups to spur changes in policy. State prescribed fire councils are organized under the national Coalition of Prescribed Fire Councils, 88See Coalition of Prescribed Fire Councils, https://www.prescribedfire.net/. which acts as a clearinghouse for individual councils and a single voice for the need to reduce hurdles to prescribed fire. The unique challenges for prescribed fire implementation in the West highlight the need for council development and adoption of policies that work in other regions.

To increase certification opportunities, states could better harness existing private training resources. Prescribed burn associations, as discussed above, provide valuable training and practice opportunities that could be used to qualify for certification.89See Diaz, Fawcett, & Weir, The Value of Forming a Prescribed Burn Association, supra n.3. In addition, The Nature Conservancy, through a cooperative agreement with the Forest Service, has a Prescribed Fire Training Exchanges (TREX) program that teaches participants through work on prescribed burns that achieve locally supported management objectives.90See The Nature Conservancy, Fact Sheet: Prescribed Fire Training Exchanges, Conservation Gateway (2019), https: //www.conservationgateway.org/ConservationPractices/FireLandscapes/FireLearningNetwork/Documents/FactSheet_TREX.pdf. The program has grown from training 68 people in 2008 to more than 600 in 2021.91See The Nature Conservancy, Prescribed Fire Training Exchanges 2008–2021, Conservation Gateway (2022), https://www.conservationgateway.org/ConservationPractices/FireLandscapes/HabitatProtectionandRestoration/Training/TrainingExchanges/Documents/TREX-graphic.jpg.

Many tribes also train their members, members of other tribes, and others on cultural burning practices.92See The Nature Conservancy, Fact Sheet: Indigenous Peoples Burning Network, Conservation Gateway (2021), https:// www.conservationgateway.org/ConservationPractices/FireLandscapes/FireLearningNetwork/Documents/FactSheet_IPBN.pdf. See also Brian Bull, Indigenous Firefighter Training Teaches Traditional Native Practices in Woodlands Management, KLCC.org (Mar. 12, 2022), https://www.klcc.org/2022-03-12/indigenous-firefighter-training-teaches- traditional-native-practices-in-woodlands-management. But few states have capitalized on tribal experience and interest in prescribed fire. California is an exception, having recently recognized tribal certification programs and given them the same treatment as the state’s own new certification program.93See Hayley Smith, Newsom Signs ‘Monumental’ Law Paving Way for More Prescribed Burns, LA Times (Oct. 7, 2021), https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2021-10-07/newsom-signs-fire-law-paving-way-for-more-prescribed-burns. See also Clark, Miller, and Hankins, Good Fires, supra n.13 (criticizing California’s regulation of cultural burning in other respects).

Having state agencies set the requirements for certification while allowing private entities to qualify burners under those requirements would separate regulatory and educational objectives and could help improve incentives for prompt, efficient certifications. Providers of private training resources have strong incentives to maintain quality, including protecting their reputations among potential participants and remaining eligible to certify burners.94Cf. Timothy D. Lytton, The Advantages of Private Certification Over Government Regulation, The Reg. Review (Oct. 6, 2014), https://www.theregreview.org/2014/10/06/lytton-private-certification/. But if a state agency wanted to maintain control over certification for some burns, it could establish different tiers of certification and allow private trainers to certify for lower tiers.95See Forest Steward Guild, Insights and Suggestions, supra n.9, at 17 (recommending states adopt multiple tiers of certification to cover different types of burns). A tiered system could also better account for the fact that landowners interested in simpler burns and prescribed fire contractors specializing in more complex burns have different training needs, timelines, and willingness to navigate bureaucracy.

Another approach states could use to expand the number of trained, qualified burners would be to give reciprocity to certified burners from other states where prescribed fire is more common. This would also allow entrepreneurial burners to more easily scale their operations. While varying climates, forest types, and other conditions mean that prescribed fire practice differs among states, this need not be an obstacle to reciprocity. In other contexts, states limit the amount of duplicated effort required when a licensed professional relocates from another state. In law practice, for instance, states admit attorneys from other states through a streamlined process rather than requiring them to retake the bar exam.96See Shari Davidson, Reciprocity: Guide to States Where You Can Practice Law, JD Supra (Aug. 19, 2021), https://www. jdsupra.com/legalnews/reciprocity-guide-to-states-where-you-7387684/. They do so even where a state requires knowledge of uncommon areas of law or has rules unique to that state. In such cases, states credit applicants for their existing license and require only that they supplement their knowledge by, for instance, attending a short seminar concerning the state’s unique rules.97See State Bar of Montana, Applying for Admission to the State Bar of Montana, https://www.montanabar.org/ Membership-Regulatory/Admissions/Admissions-Home (discussing the “Montana Law Seminar” that attorneys seeking admission by motion must complete); Texas Board of Law Examiners, Admission Without Examination Information, https://ble.texas.gov/admission-without-examination (requiring applicants to complete a free course on Texas law). Washington and New Mexico have proposed, but not yet implemented, a reciprocity process for out-of-state burners. And California allows experienced burners to skip certain prerequisites to sit for its certification program.

Recommendation for States

- Harness private training resources, such as those from prescribed burn associations and tribal organizations. Private groups can provide valuable training and practice opportunities that could be used to qualify for burner certification.

- Establish different tiers of certification and allow private trainers to certify for lower tiers if states want to maintain control over certification for some burns.

- Adopt reciprocity for burner certification in other states. If regulations, fuels, weather conditions, or other particular factors warrant additional, state-specific training, states should require only supplementary training for those factors.

4. Liability Regimes

Improve Liability Regimes to Align Private Risk and Public Benefits

Despite the benefits of managing land with prescribed fire, a large body of research shows that many private landowners decline to adopt the practice due to fear of liability.98See Carissa Wonkka et al., Legal Barriers to Effective Ecosystem Management: Exploring Linkages Between Liability, Regulations, and Prescribed Fire, 28 Ecological Applications 2382, 2383 (2015), https://bit.ly/3yM0Ojk (collecting studies). Although the following examples are exceedingly rare, a prescribed fire presents several potential risks: smoke could cause a car accident on a nearby road, a fire could escape containment and require costly suppression efforts, and an escaped fire could cause significant damage to neighboring property and communities.

Ordinarily, holding people liable for the harms they create works well to encourage responsible behavior and discourage carelessness by requiring people to internalize risks and costs imposed on others.99See, e.g., Henry N. Butler, A Defense of Common Law Environmentalism: The Discovery of Better Environmental Policy, 58 Case W. Res. L. Rev. 705 (2008); Roger Meiners & Bruce Yandle, The Common Law: How It Protects the Environment, PERC Policy Series (1998), https://www.perc.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/PS13.pdf. In the prescribed burn context, however, it has produced closer to the opposite result. If landowners bear all of the costs and risks of prescribed fire while capturing only a portion of its benefits, they will likely decline to use the tool even when the total benefits far exceed the risks. While fear of liability is a major factor discouraging landowners from using prescribed fire, the actual risks of an escape are quite small. The Forest Service, which ignites about 4,500 prescribed fires per year, reports that only 0.16 percent escape.100See Forest Serv., National Prescribed Fire Program Review 7 (2022), https://www.wildfirelessons.net/HigherLogic/ System/DownloadDocumentFile.ashx?DocumentFileKey=d19e4406-ac0a-c1c2-273d-e4577e5a56e8&forceDialog=0. The liability risks discussed here do not affect the Forest Service the same way they do private landowners. Courts have effectively insulated the agency from any liability for its contributions to wildfire risks. See Lawson Fite & David Bechtold, Fire Liability Imbalances–An Issue Worth Revisiting?, 35 ABA Nat. Res. & Enviro. 50 (2021). Studies of prescribed fire use on private land similarly show a risk of escape below 1 percent.101See John R. Weir et al., Liability and Prescribed Fire: Perception and Reality, 72 Rangeland Ecology & Management 533, 535–36 (2019), https://agrilife.org/kreuter/files/2020/01/Liability-and-Prescribed-fire_Perception-and-reality.pdf. See also J. Morgan Varner et al., Increasing Pace and Scale of Prescribed Fire via Catastrophe Funds for Liability Relief, 4 Fire 77 (2021), https://www.mdpi.com/2571-6255/4/4/77/pdf. But even these low figures may give a misimpression about the magnitude of the risk because many escapes cause only minor damage, such as burning a small area of neighboring forest or grassland.102See Weir et al., supra n.4, at 535. As the authors of a recent study put it, “the risk of using prescribed fire is often considered unacceptable even though [it] . . . is far less than driving a car.”103See id.

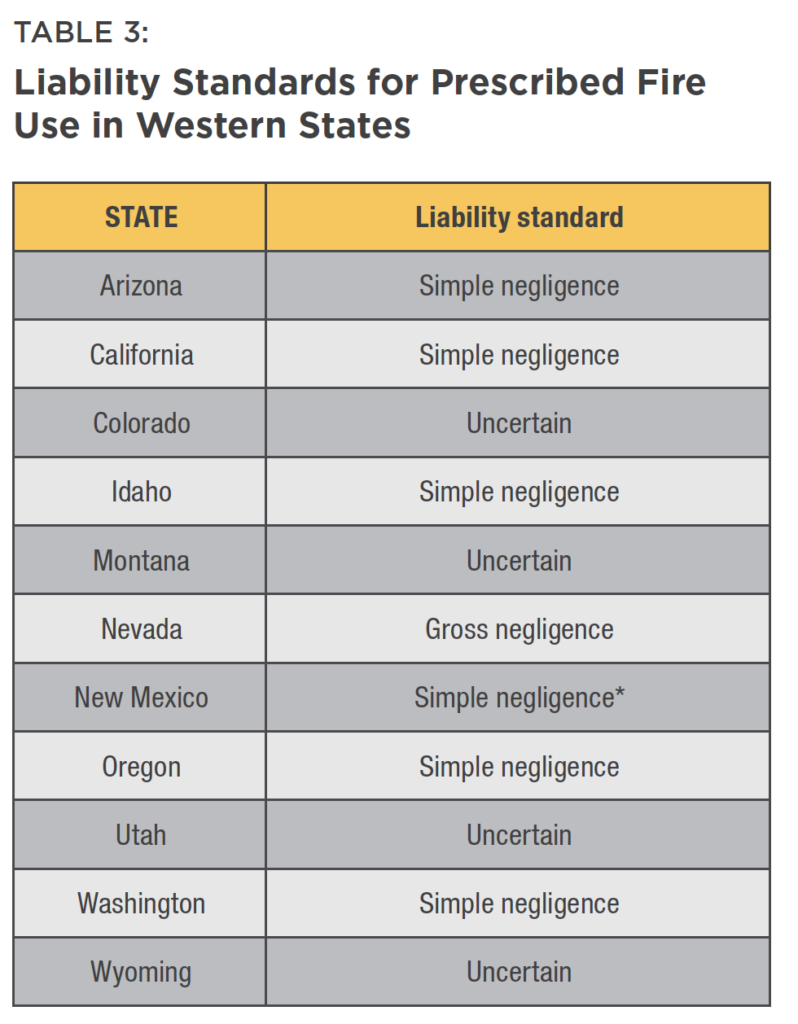

How liability is determined varies by state, as shown in Table 3. There are three basic standards: (1) Under strict liability, a person is liable for any damages resulting from their actions regardless of the steps they took or could have taken to reduce the harm or risk. This standard commonly applies to actions that cause pollution to spread to neighboring land as well as unusually dangerous activities.104See Meiners & Yandle, The Common Law, supra n.2. (2) Under simple negligence, a person is liable if harm results from their carelessness or failure to take reasonable steps to reduce risks. It is intended to encourage people to balance the benefit of their actions against the potential harm.105See United States v. Carroll Towing Co., 159 F.2d 169, 174 (2d. Cir. 1947). See also Peter Z. Grossman, Reed W. Cearley, & Daniel H. Cole, Uncertainty, Insurance and the Learned Hand Formula in Law, Probability and Risk vol. 5, 1 (2006). And (3) under gross negligence, a person is liable for conduct that shows reckless disregard for others and their property.106See Gross Negligence, Black’s Law Dictionary (8th ed. 1999). Although more often used as the trigger for imposing punitive damages, gross negligence has also been used as a standard for determining liability in situations with large social benefits and small or no private benefits. A common example is Good Samaritan laws, which protect someone who inadvertently causes harm while offering aid to a stranger in an emergency.107See Brian West & Matthew Varacallo, Good Samaritan Laws (2021), https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK542176/ #:~:text=Good%20Samaritan%20laws%20give%20liability,the%20same%20or%20similar%20circumstances (explaining that these laws are motivated by the recognition that “we are improved as a society if the potential rescuers (i.e., the good Samaritans) are solely concerned about helping a person in need as opposed to worrying about the possible liability associated with assisting their fellow man or woman”).

In theory, these standards should lead to the same results if rights are clearly defined and there are low costs for parties to bargain with each other.108See Ronald Coase, The Problem of Social Cost, 3 J. Law & Econ. 1 (1960). See also Meiners & Yandle, The Common Law, supra n.2. In the prescribed fire context, however, liability risks have discouraged the practice even where the benefits far exceed the costs. There are several reasons for this.

First, landowners considering using prescribed fire often do not have reliable information about the risks of escape in similar circumstances and whether an escape would cause significant damage. National statistics, like those discussed above, may be insufficient comfort for a western landowner surrounded by poorly managed forests in a high wildfire-risk area. Where risks are uncertain, people are likely to assume the worst and be more risk averse than they would be with more confidence in the extent of risks.109See Grossman, Cearley, & Cole, supra n.8. The worst case scenario—an escaped fire that destroys homes and causes human casualties—could easily bankrupt a private landowner if she is liable for the damage. Thus, this uncertainty can have a powerful effect on decision-making.

*New Mexcio imposes double liability for damages from escaped burns. For example, if an escaped burn causes damages of $100,000, then the burner must pay $200,000 in damages.

Second, rights are not always clearly defined. Several states have never clarified the liability standard for prescribed fire practitioners, leaving them to guess.110See Mark A. Melvin, National Prescribed Fire Use Survey Report, Coalition of Prescribed Fire Councils Tech. Rep. (2018), https://www.stateforesters.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/2018-Prescribed-Fire-Use-Survey-Report-1.pdf. When a liability standard is uncertain, people are likely to “overcomply” by either avoiding the activity that could trigger liability or taking excessive precautions to minimize risks.111See John E. Calfee & Richard Craswell, Some Effects of Uncertainty on Compliance with Legal Standards, 70 Virginia L. Rev. 965 (1984). As noted in Table 3, four western states have not clearly established what liability standard applies to escaped prescribed fires. Additional uncertainty exists over how liability would be allocated between a landowner and a burn boss contracted to plan and oversee a prescribed fire that escaped.112See Changyou Sun, Common Law Liability for Landowners When Using Prescribed Fires on Private Forest Land in the Southern United States, 53 Forest Science 562 (2007). Although unresolved, there is some precedent in California (and outside the West) for holding landowners liable for the actions of employees and contractors.113See Presbyterian Camp & Conference Centers, Inc. v. Superior Court, 12 Cal.5th 493 (2021) (holding a church camp liable for a fire inadvertently set by one of its employees). See also Sun, Common Law Liability, supra n.15. If the landowner has more resources than the burn boss, she may be a more attractive target of a lawsuit.

Third, landowners cannot easily negotiate with everyone who may benefit from their use of prescribed fire. As recent years have shown, an area managed with prescribed fire may lower the intensity or severity of a wildfire, allowing it to be contained before spreading to other areas.114See Henry Fountain, This Vast Wildfire Lab Is Helping Foresters Prepare for a Hotter Planet, N.Y. Times (Jan. 5, 2022), https://www.nytimes.com/2022/01/05/climate/fire-forest-management-bootleg-oregon.html. Prescribed fire may also promote habitat for wildlife valued by hunters and conservationists.115U.S. Forest Serv. Pacific-Northwest Research Station., Using Prescribed Fire to Enhance Wildlife Habitat, https://www.fs.usda.gov/pnw/pnw-research-highlights/using-prescribed-fire-enhance-wildlife-habitat#:~:text=In%20fact%2C%20prescribed%20fires%20can,like%20elk%20and%20their%20offspring (last visited Oct. 17, 2022). But the landowner who produces these benefits cannot exclude others from them or charge for their enjoyment. Thus, she will likely weigh the costs of implementing a prescribed fire against only those benefits accruing to her land, rationally ignoring the benefits accruing to surrounding landowners, communities, or the public generally. Instead, she may choose other management techniques that have lower risks but also yield fewer benefits.116See Dirac Tidwell et al., First Approximations of Prescribed Fire Risks Relative to Other Management Techniques Used on Private Lands, 10 PLOS One 13 (2015), https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0140410 (finding that mechanical thinning is more likely to cause injury or death than a prescribed fire, although this risk is limited to a relatively smaller area and fewer people). Of course, in extreme cases, timber harvesting and thinning could start a wildfire which could generate significant liability. See United States v. Sierra Pacific Industries, Inc., 862 F.3d 1157, 1163–65 (9th Cir. 2017) (describing a settlement in a case where a timber company’s employee allegedly caused through negligence a wildfire that burned Forest Service land).

Fourth, many of the factors contributing to the liability risk are outside of landowners’ control. This is obvious with respect to an “act of God,” like a sudden shift in the wind that causes a prescribed fire to escape. But perhaps more importantly, the effects of an escaped fire depend on how surrounding lands are managed. A fire that escapes into a neighboring wellmanaged forest may cause only minor damage, but a fire that escapes into a forest with unhealthy levels of fuel may become a catastrophic wildfire that spreads into developed and residential areas.

In other contexts, rules have been developed for dividing responsibility in situations where someone contributed to a risk or located new development near a known risk.117See Jonathan Wood, Coming to the Wildfire Nuisance: Using Property Rights to Restore National Forests and Avoid Moral Hazard, CGO Working Paper (forthcoming) (available from author). See also Contributory Negligence Doctrine, Black’s Law Dictionary (8th ed. 1999). But these rules have not been extended to the prescribed burn context. And it would be difficult to do so due to the prevalence of federal land in the West and federal agencies’ immunity from liability for unsafe wildfire conditions, damage from fire that spread from federal to non-federal land, and other wildfire-related harms.118See Wood, Coming to the Wildfire Nuisance, supra n.20 (suggesting that nuisance law may provide an alternative to after-the-fact liability for a wildfire, especially if paired with adoption of a “coming to the nuisance” defense to avoid moral hazard); Fite & Bechtold, supra n.3 (suggesting that the Forest Service immunity from wildfire liability is unfair when the agency readily sues its neighbors for fires and, for that and other reasons, should be reconsidered).

Due to the law imposing liability for escaped prescribed fires while largely ignoring inaction that allows dangerous conditions to develop, inaction can be the safer approach for private landowners from a liability perspective. This is so even though catastrophic wildfires are orders of magnitude more dangerous than prescribed fires. According to one study, wildfire- related fatalities exceed those from prescribed burns by 3,350 percent.119See Tidwell et al., supra n.19, at 9. Wildfires also destroy more structures, degrade more forests and wildlife habitats, and diminish more resources of other types.120See Holly Fretwell & Jonathan Wood, Fix America’s Forests: Reforms to Restore National Forests and Tackle the Wildfire Crisis, PERC Public Lands Report (2021), https://www.perc.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/fix-americas-forests- restore-national-forests-tackle-wildfire-crisis.pdf.

The question, therefore, is how to address liability rules to improve incentives for landowners to use prescribed fire, while not going so far as to encourage its unsafe use. The low-hanging fruit is to address uncertainty. The risks of a prescribed fire escaping and causing damage may vary by climate, forest type, and other factors. Reliable, local information about those risks would give landowners more confidence about deciding whether to conduct prescribed fires. So too would clarifying the liability standard that a state will apply to escaped fires and the approach it will follow to allocate liability between landowners and contractors who implement burns. These changes would allow landowners to rationally compare liability risks with the benefits of using prescribed fire, rather than assuming the worst.

Another effective reform would be to narrow the risk that falls on the individual landowner. As in the case of a Good Samaritan coming to a stranger’s aid, prescribed fire produces large benefits that are not captured by the person deciding whether to burn. Consequently, a gross negligence standard can better encourage landowners to adopt the practice compared to a strict liability or simple negligence regime.

Indeed, adoption of a gross negligence standard has already proven effective at doing so in the Southeast. A study of prescribed fire use in border counties in Alabama, Florida, and Georgia found that private landowners used prescribed fire more often and burned larger areas when governed by a gross negligence standard compared to landowners in neighboring states governed by simple negligence.121See Wonkka et al., Legal Barriers, supra n.1, at 2386–87. On average, there was a 10 percent increase in the area managed with prescribed fire under a gross negligence regime.122See id. at 2387. As shown in Table 3, five states follow a simple negligence approach, with New Mexico uniquely requiring liable landowners to pay two times the amount of damage they cause.

To address fears that a gross negligence standard would lead to unsafe practices, several states have paired this reform with additional policies to encourage careful use of prescribed fire, although practitioners have expressed concern when those policies are onerous or vague.123See Stephen McCullers, Note, A Dangerous Servant and a Fearful Master: Why Florida’s Prescribed Fire Statute Should Be Amended, 65 Fla. L. Rev. 587 (2013). California, for instance, recently enacted legislation providing that burners who complete a state certification process will be liable for the costs to suppress an escaped fire only if they were grossly negligent.124See Cal. S.B. 332 (2021). Other states have adopted a gross negligence standard but only for prescribed burns that comply with state-determined regulatory standards. Georgia, however, has adopted a gross negligence standard without pairing it with any additional regulatory restrictions.

A gross negligence standard effectively shifts liability from the person carrying out a prescribed fire to neighboring landowners and communities who may be harmed by an escape, which they may perceive as unfair.125See Letter from Mike Christianson, President of Montana Forest Owners Association, to Chairman and Members of Montana Environmental Quality Council (Mar. 20, 2018), https://leg.mt.gov/content/Committees/Interim/2017-2018/ EQC/Meetings/Mar-2018/fire-comments.pdf (opposing prescribed fire legislation over concerns it would shift liability to innocent landowners). Considering the lack of a prescribed fire culture in much of the West and the potential for neighboring landowners and communities to block its use, a complementary approach would be to instead share the total risk between the landowner and others who benefit from expanded use of prescribed fire. The next section addresses an innovative solution to this problem.

Recommendation for States

- Broadcast reliable, local information about the risks of a prescribed fire escaping and causing damage based on climate, forest type, and other factors.

- Clarify the liability standard that applies to escaped fires and the approach to allocating liability between landowners and contractors who implement burns.

- Consider adopting a gross negligence standard to narrow the risk that falls on the individual landowner whose use of prescribed fire produces public benefits.

5. Catastrophe bonds

Harness Catastrophe Bonds to Invest in Ecosystem Health and Forest Resilience

While reducing landowners’ liability for escaped prescribed fires is essential to expanding use of the tool, shifting that risk to surrounding landowners and communities may undermine support for “good fire.”126See J. Morgan Varner et al., Increasing Pace and Scale of Prescribed Fire via Catastrophe Funds for Liability Relief, 4 Fire 77 (2021), https://www.mdpi.com/2571-6255/4/4/77/pdf?version=1634796391. This concern is especially acute in the wake of a high-profile escape, such as the Hermit’s Peak Fire that started as an escaped Forest Service prescribed fire in 2022 and eventually burned over 300,000 acres, destroyed nearly 1,000 structures, and cost more than $100 million to extinguish.127See Eric Westervelt, New Mexico Wildfire Sparks Backlash Against Controlled Burns. That’s Bad for the West, Nat’l Public Radio (May 20, 2022), https://www.npr.org/2022/05/20/1099625787/new-mexico-wildfire-sparks-backlash-against- controlled-burns-thats-bad-for-the-w. Leaving the victims of such fires with no recourse can be devastating, especially for families and communities who lack the resources to rebuild and may have limited access to insurance.128See Varner et al., Increasing Pace and Scale, supra n.1, at 6–7. See also Monique Dutkowsky & Holly Fretwell, California Can Learn from Colorado on Protecting Homes from Wildfire Risks, O.C. Register (Nov. 13, 2020), https://www.ocregister. com/2020/11/13/california-can-learn-from-colorado-on-protecting-homes-from-wildfire-risks/ (discussing California restrictions on market-price insurance and its impact on the availability of insurance). Doing nothing, however, leaves communities vulnerable to an even more catastrophic wildfire, against which they also have no recourse.