This special issue of PERC Reports examines the Endangered Species Act with an eye toward improving the incentives for species recovery. Read the full issue.

It was a bison. At least, that’s what it looked like at first glance. We were deep in the backcountry of Yellowstone National Park fishing a creek that meandered through an expansive meadow. My wife was casting toward a cutbank across the creek, hoping to entice a rising cutthroat trout. Something caught my eye. Above the bank was a grove of willows, and from them emerged the “bison.” It was a grizzly bear.

In bear country, there are sightings and there are encounters. Most people who see a grizzly do so from afar, capturing a glimpse of one off in the distance or from the side of a road in Yellowstone, Grand Teton, or Glacier National Park as it goes about the business of being a bear. An encounter is different. In an encounter, it’s just you and the bear unintentionally running into each other, and the bear is dialed in on you. This would be my fourth grizzly encounter in 15 years.

As startling as each encounter is, the fact that they’re becoming more frequent should come as no surprise. In areas like the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, grizzlies are thriving and on the move. Currently listed as a threatened under the Endangered Species Act, grizzly bears that have long lived in isolated populations are now venturing out of their regions and reclaiming old territory. In Montana, their expanding numbers mean they are being seen in the Shields Valley, the Pryor Mountains, outside of Helena, in the Big Snowy Mountains, and in the Little Belt Mountains—places that, in many cases, grizzlies have not inhabited in more than 100 years.

The Yellowstone grizzly bear is recoverd, but it remains listed. In this sense, grizzlies are an example of the best and the worst of the Endangered Species Act.

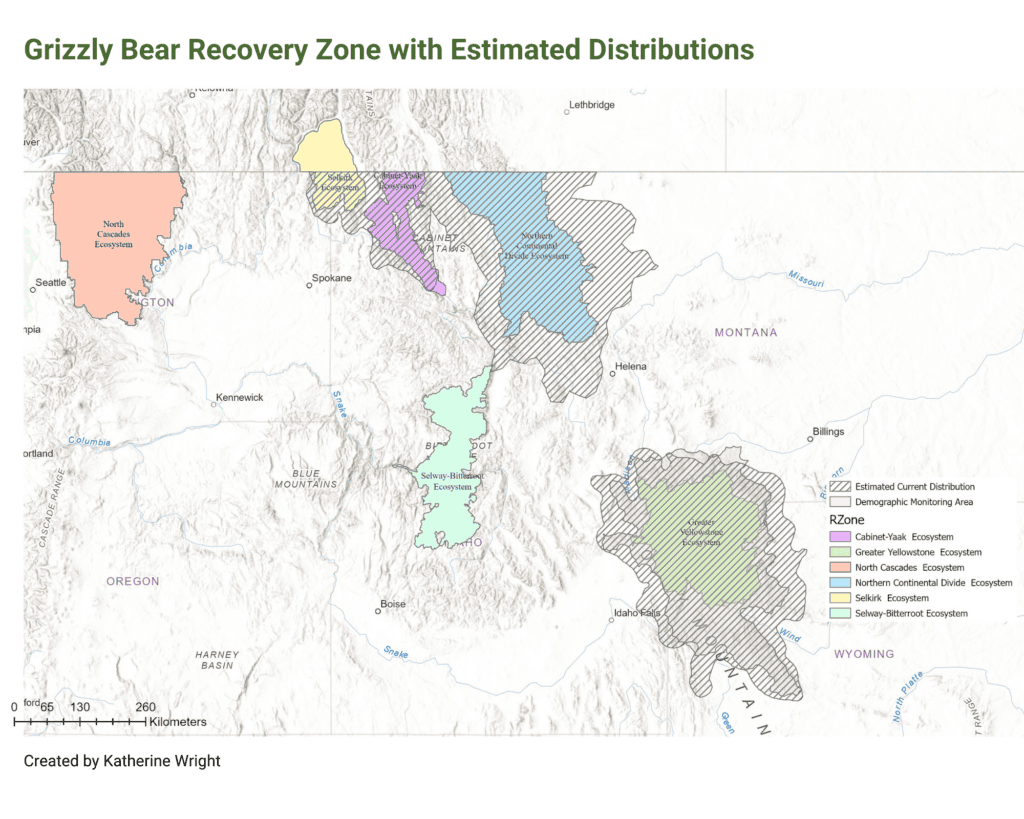

Scientists believe that the ranges of the two largest populations outside of Alaska—the Greater Yellowstone and the Northern Continental Divide Ecosystems—are now separated by a mere 35 miles. As High Country News describes it, “two islands becoming a continent.” The two populations combined are estimated to total more than 2,000 bears. In recent decades, Yellowstone grizzlies have tripled their range. It’s a far cry from 48 years ago, when the grizzly was first put on the endangered species list, and biologists believed there were as few as 136 grizzlies left in the Yellowstone region, with only 30 breeding females. Their population has skyrocketed in the half century since the Endangered Species Act was passed.

Unfortunately, rather than being universally celebrated for its progress, the grizzly has become the subject of persistent conflict. Thankfully, for threatened species like the bear, there’s a way to exchange endless disputes for positive incentives toward recovery. While it wouldn’t require any changes to the venerable Endangered Species Act, it would require something endangered species policy has all too often lacked over the past 50 years: creativity.

A Hairy Situation

There is a billboard along the highway in Paradise Valley, Montana, with giant letters that read, “Delist Grizzly Bears to Support a Conservation Success Story.” It was erected recently by a local group and has received mixed reviews.

But by almost every metric, grizzly bear recovery is a remarkable conservation success story. Why? First, the bears are among the slowest reproducing mammals in North America. That’s why their multiplication in population is so significant. Second, they require enormous amounts of habitat, as much as 600 square miles for an adult male. Third, they sometimes kill people, something I was reminded of a year ago as I watched a helicopter retrieve the body of an elk antler collector mauled to death by a grizzly he surprised in the backcountry in Paradise Valley.

Despite these challenges, government agencies have poured millions of dollars into the recovery of the iconic bear in an effort to delist the species. From 1994 to 2020, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and states combined to spend nearly $200 million. After the bear’s listing in 1975, state and federal managers created the Interagency Grizzly Bear Committee to develop a recovery plan for each of six designated recovery zones (see map). The explicit aim was to recover and delist the species. Some of the recovery zones already had established grizzly populations, while others, such as the North Cascades and Bitterroot, lacked bears but harbored suitable habitat.

For the Yellowstone grizzly population, the recovery plan required 1) maintaining a minimum population size of 500 animals and 48 females with cubs of the year, 2) having 16 of 18 bear management units occupied by reproducing females, and 3) limiting mortality to established levels according to age and gender. The Yellowstone population has exceeded all recovery criteria since at least 2003, with some benchmarks met earlier than that.

Simply put, the Yellowstone grizzly bear is recovered, but it remains listed. And, in this sense, grizzly bears are an example of the best and the worst of the Endangered Species Act, a law designed to prevent the extinction of animals and provide for their recovery and delisting.

The fact that the species has recovered yet hasn’t been delisted has major implications. Its increase in numbers leads to more conflicts with states and landowners, who then have limited flexibility to address those conflicts. Encountering any listed species can bring red tape, land-use restrictions, and lengthy consultations with federal agencies. Ranchers, farmers, and other landowners, along with state agencies, end up bearing the costs in terms of money and time. And the strict regulation that accompanies a listed species means that even efforts that aim to benefit the bear, such as state biologists moving problem bears away from livestock-heavy areas, can be stymied. The fallout is unlikely to win listed species—especially large predators like the grizzly—many local fans.

After decades of work culminating in recovery goals being met and relying on up-to-date science, the Fish and Wildlife Service twice—in 2007 and 2017—issued rules to delist the Yellowstone grizzly. Both times delisting turned out to be as elusive as the pot of gold at the end of the rainbow. Fearing state management of the bears, environmental litigants challenged both efforts in court. Each time, judges put the grizzly bear back on the list and sent the Fish and Wildlife Service back to the drawing board.

The repeated delisting whiplash put in motion a chain reaction of responses borne of frustration. Members of Congress from the affected states—Montana, Wyoming, and Idaho—introduced bills to legislatively delist the bear and bar judicial review, as had been done previously with endangered Yellowstone wolves entangled in serial litigation. Members of Congress not from grizzly states filed legislation to permanently put the bear under federal management and bar hunting if it were ever delisted.

At the same time, Montana filed new petitions to delist the Northern Continental Divide population, and Wyoming filed another petition to delist the Yellowstone population. Both are now undergoing comprehensive status reviews by the Fish and Wildlife Service to determine if either population warrants delisting. Those decisions, expected within the next year, will surely result in more litigation and conflict.

Likewise, battles over delisting have hampered efforts to reintroduce and expand bear populations in the still-struggling recovery areas, such as the North Cascades and Bitterroot, over the regulatory consequences for landowners and states.

So, billboards go up. As David Willms, associate vice president at the National Wildlife Federation, writes in a new book volume The Codex of the Endangered Species Act: The Next 50 Years, “After nearly 50 years of recovery efforts that most would consider remarkable, grizzly bears are becoming more and more polarizing due to the differences of opinion surrounding delisting.” Despite this conservation success story, we have found a way to snatch defeat from the jaws of victory.

A Bearable Alternative

The cycle is now clear. A petition to delist the grizzly and return management of the bear to the states is filed. Federal bear managers, relying on sound science, determine recovery goals have been met. The Fish and Wildlife Service tries to delist the grizzly. A litigious environmental group sues the Fish and Wildlife Service. A judge orders the agency to relist the bear. Another petition to delist the grizzly is filed by the states. It seems each decade brings a delisting and relisting. Wash, rinse, repeat.

The cycle has repercussions for the Endangered Species Act. It penalizes rather than rewards those who have worked to conserve species. It creates disincentives for recovery and innovation. It makes it impossible to see a path to delisting. It strips other imperiled species of much needed resources. It diminishes support from states and landowners. And it stymies the ultimate goal of the Endangered Species Act: to recover species.

Is there a way to break the cycle so that the Endangered Species Act is allowed to work as intended, incentives are provided for species recovery, and management of recovered species returned to the states? It turns out for threatened species like the grizzly bear the answer is yes.

Currently, delistings result in abrupt changes to management of species from nearly complete federal control to nearly complete state control. If states gradually resumed management responsibility, however, they could demonstrate—while a species retained some federal oversight—their ability to manage it effectively.

For threatened species, the Endangered Species Act allows the Fish and Wildlife Service to provide management flexibility to states and landowners for certain activities through tailored rules. Rather than blindly applying the strictest prohibitions under the law, the act directs the service to customize regulations to the needs of threatened species. The agency can prohibit activities especially harmful to a species while staying out of the way of activities with trivial or beneficial impacts. These tailored regulations are often called 4(d) rules, named after the section of the act that grants this authority.

One of the benefits of a tailored 4(d) rule is that it can help blunt the perceived or real impacts of a listing decision while providing incentives for recovery. But used creatively, it can also incrementally shift authority for management of a threatened species back to the states “by allowing states to manage a largely recovered, but still listed species, as though it were delisted,” as Willms, of the National Wildlife Federation, puts it.

And there is the big idea, advanced by both Willms and PERC researchers: Craft a “roadmap” under 4(d) for recovering species that incrementally reduces federal regulation as populations hit objective recovery benchmarks. This would create a system of incentives and rewards for recovering the species—all while the grizzly bear is still listed. As benchmarks are achieved, triggers would allow for more flexibility in managing the bear, such as letting states take the lead in permitting “take” under the act or deciding when and how to move bears around. Eventually, with all benchmarks achieved, the states would earn full management authority. This would allow states to prove the effectiveness of their management plans while building trust with environmentalists who would like to see federal oversight maintained.

There is precedent for this approach, which the act already uses for its “post-delisting” process. Once a species is delisted, the federal government is charged with monitoring how a state manages the species over the next five years. If a species slides into an alarming decline, the Fish and Wildlife Service can quickly relist it using an emergency provision. To date, 66 species have been delisted due to recovery, and not once has the Fish and Wildlife Service found it necessary to take management back from the states through this post-delisting process.

The Endangered Species Act furnishes the tools to make grizzly bears a prototype for getting recovery right. We just have to embrace them.

Applying the solution to the grizzly would simply front-load this back-loaded process. A period of full state control prior to the grizzly delisting could substantially reduce incentives to litigate against the delisting. Both the Fish and Wildlife Service and the states could easily prove there was no abrupt change in management. An eventual delisting would become a mere formality.

Unlike the current cycle, the benefits of this new approach would be seemingly endless. “It may facilitate faster recovery,” Willms writes, “and ensure that once the species is delisted it will not warrant relisting in the foreseeable future. Additionally, it creates certainty and predictability for the regulated community, may reduce litigation upon delisting, restore trust in the Endangered Species Act, and even free up limited resources of the Fish and Wildlife Service to be redeployed to invest in other federally listed species.”

In the end, it is possible, even likely, that Montana and Wyoming prevail in their petitions to delist both the Yellowstone and Northern Continental Divide grizzly populations. But thanks to the cycle, it is also likely that, if the populations are declared recovered, those decisions will be challenged in court, and the grizzlies could be put back on the endangered species list. States would lose yet another decade and expend untold resources on an already-recovered animal. A 4(d) alternative could provide states with their desired outcome, just through a different pathway.

A Cascading Experiment

Getting grizzly bear management right with existing populations would also help get management right with reintroduced populations. Section 10(j) of the Endangered Species Act gives the Fish and Wildlife Service authority to introduce so-called experimental populations to aid in the recovery of listed species. Since 1982, the service has designated more than 80 experimental populations, including black-footed ferrets, whooping cranes, and various species of wolves. With regard to grizzly bears, the idea dates back to 1919, when the naturalist Enos Mills suggested in his tome The Grizzly that “the population might be more quickly affected by restocking. A few grizzlies could be trapped in Yellowstone and set free in these other National Parks.”

In the state of Washington, a proposal by the Fish and Wildlife Service to reintroduce grizzlies to the North Cascades recovery zone has been met with a mix of state support and local skepticism. The latter recalls a previous proposal to reintroduce the bear to the Bitterroot Mountains. Despite crafting a 10(j) rule and plan to relocate the bear in 2000, local opposition to grizzly reintroduction caused the service to abandon the plan.

As the delisting back and forth plays out in Montana, Wyoming, and Idaho, people who live, work, and play in the North Cascades wonder what it will mean for them. The recovery zone there, which includes North Cascades National Park and portions of several national forests, has no grizzly bears today. Most of the bears in the region were killed by trappers, bounty hunters, and miners by the 1860s. And there has been no evidence of a grizzly bear being there since 1996.

Proactively establishing new populations of listed species can be an effective way to recover them, but the devil is in the details that regulate reintroduced species. Accompanying relocated wildlife with heavy-handed regulation introduces not just a species but a liability for surrounding communities and nearby landowners.

Fortunately, the Endangered Species Act provides ample flexibility to avoid this outcome for experimental populations. These populations are treated as threatened, meaning the only regulatory burdens on landowners and communities are those the service chooses to impose. Limiting regulation of activities that may incidentally harm members of the species, including traditional land management or use, is a way to encourage local buy-in. But this approach only works if the service uses its discretion effectively and works with states and private landowners as partners.

Don Striker, superintendent of North Cascades National Park and a member of the Interagency Grizzly Bear Committee, calls the 10(j) approach “a difference maker” by giving states more flexibility and avoiding burdensome regulation. Striker has prioritized communicating with county officials and other locals on the soon to be released 10(j) rule.

But in the case of the North Cascades, the promise of flexibility and light regulation is not a guarantee. It’s more of a race against time. The North Cascades Ecosystem straddles Washington’s neighbor to the north, British Columbia. Sightings of grizzlies on that side of the international boundary have increased, and the Canadians and First Nations have been working to grow the grizzly population. If bears from Canada disperse into North Cascades National Park, then the grizzlies will not be treated as an experimental population but rather as a threatened species, with significant regulatory consequences.

To avoid stricter regulation and even more local opposition, Superintendent Striker believes an experimental population provides the best route to recover grizzlies in the area—essentially choosing sooner, on terms favorable to states and communities, rather than later, under more onerous circumstances. Others, however, simply don’t want the grizzly bear there, regardless of flexibility in management. As then Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke, who supported reintroduction but recognized legitimate concerns, said, “This is not the reintroduction of a rabbit. This is the reintroduction of the grizzly.” If bears from Canada get to the North Cascades first, they’ll make the potential for an experimental population moot.

The Wilderness King

The Endangered Species Act furnishes the tools to make grizzly bears a prototype for getting recovery right. We just have to embrace them. Both 4(d) and 10(j) provisions can provide user-friendly roadmaps for recovery if used more effectively—more creatively. By better aligning incentives with recovery and securing local buy-in, the next 50 years of the Endangered Species Act can see a recovery revolution. And I’ll likely have more grizzly bear encounters.

You have good days and bad days with grizzly bears. The grizzly directly across the stream from my wife and I stood broadside, its chocolate and silver-tipped fur rippling in a warm afternoon breeze, looking much as Enos Mills described him more than a century ago—“King of the Wilderness World.” Likely no more than 40 feet away, it gave us an agitated look, wondering what had disturbed its afternoon nap. I leaned toward my wife and whispered, “Slowly pull the bear spray out of my backpack.” She—rightly—gave me an incredulous look.

For what felt like an eternity, the bear did not move, unperturbed but dialed into our every move. It was oblivious to the controversies stirred up over its recovery. Impressive. Majestic. Terrifying. Would it charge? Would it run away? This would be a good day.