Introduction

After surges in visitation over recent decades, America’s national parks are struggling to keep pace with their popularity. Despite the increasing numbers of visitors, the National Park Service budget remains stagnant.1Tate Watkins, “How We Pay to Play: Funding Outdoor Recreation on Public Lands in the 21st Century,” PERC Public Lands Report (2019); Allison Pohle, “National Parks Are Overcrowded and Closing Their Gates,” The Wall Street Journal, June 13, 2021; Allison Pohle, “Crowded National Parks Have Turned to Reservations. Some Are Considering Keeping Them,” The Wall Street Journal, September 23, 2021. Today, the park system collectively needs an estimated $22 billion for overdue maintenance and repairs.2National Park Service, “By the Numbers,” Deferred Maintenance & Repairs, accessed October 16, 2023. The effects are seen in potholed roads, crumbling bridges, dilapidated campgrounds, failing sewer systems, condemnable employee housing, and countless other deteriorating park assets that have lacked adequate upkeep.

The recreation fee system allows parks to raise revenue that can help meet their growing needs. It has enabled some parks to take part in, if not yet fully realize, their own rescue. One reform, however, could appreciably increase revenue from the fee system: implementing a modest surcharge for international visitors. Approximately 14 million people visit national park sites from other countries annually, or more than one-third of all foreign visitors to the United States.3Overseas visitation to national parks was consistently estimated to be nearly 14 million for several years prior to the Covid-19 pandemic. International Trade Administration, National Travel and Tourism Office, “Market Profile: Visit National Parks/Monuments”; U.S. Travel Association, “Highlights of U.S. National Park Visits by Overseas Travelers,” (undated). If each international visitor to a U.S. national park paid a $25 surcharge, it could raise an estimated $330 million, nearly doubling recreation fee revenue for the park system.4See Figure 1 below for assumptions and a range of estimates for potential revenue from a surcharge on international visitation.

Crucially, this additional revenue would be dedicated to maintaining ailing parks and improving stewardship of them. The majority of park fee receipts are retained and spent where collected, as superintendents and on-the-ground staff see fit. The model empowers local managers who best know their parks—and the needs they face—to decide how to spend funds. Ultimately, additional fee revenue would help ensure all visitors can continue to enjoy an incredible experience at U.S. parks.

This brief provides an overview of the funding challenges facing U.S. national parks. It then discusses how parks are currently funded, including through the current visitor fee system, and highlights evidence suggesting a surcharge on international visitation could substantially increase park revenue. It also examines how fees are structured for local and foreign visitors at selected parks around the world. Finally, it offers recommendations for tailoring fees for overseas visitors to America’s national parks.5This brief uses the terms “overseas visitors,” “international visitors,” “foreign visitors,” and “visitors from abroad” interchangeably and to mean any visitors to U.S. national parks who do not live permanently in the United States. This usage is consistent with the way that the National Travel and Tourism Office reports data on travel trends of “residents of overseas countries.” International Trade Administration, National Travel and Tourism Office, “Market Profile: Visit National Parks/Monuments.”

Dozens of the world’s most high-profile national park systems charge overseas visitors more than locals. Adopting a surcharge for visitors from abroad at U.S. national parks could significantly increase revenue, providing parks with more funding to address maintenance and improve visitor experience.

Approximately 14 million people visit national park sites from abroad annually, or more than one-third of all foreign visitors to the United States.

If each international visitor to a U.S. national park paid a $25 surcharge, it could raise an estimated $330 million, nearly doubling total recreation fee revenue for the park system.

Entry fees account for a small fraction of the total trip costs for international visitors to U.S. national parks. Moreover, existing research suggests that higher fees would have a negligible effect on park visitation from international travelers.

A Higher Level of Stewardship

In dozens of countries, park visitors from abroad pay more than locals for entry.6 Not all countries charge entry fees to visit national parks. Examples of countries that do not charge for entry include relatively high-income nations such as Denmark, France, New Zealand, Norway, Sweden, and the United Kingdom. Of countries that charge fees, approximately three dozen charge non-citizens more than citizens. Hugo Van Zyl, James Kinghorn, and Lucy Emerton, “National Park Entrance Fees: A Global Benchmarking Focused on Affordability,” Parks 25, no. 1 (2019): 42-43. A higher charge levied on foreign visitors reflects their general ability and willingness to pay more. After all, the price of admission at a national park is generally a fraction of overall trip costs for visitors, especially those from abroad.7National Park Entrance Fees, Van Zyl, Kinghorn, and Emerton; Stefano Pagiola et al., “Generating Public Sector Resources to Finance Sustainable Development: Revenue and Incentive Effects,” World Bank Technical Paper No. 538 (2002): 54. Asking international tourists who do not support U.S. national parks through taxes to pay a little more to see them is not only reasonable, it would also provide additional resources to improve the stewardship of our “crown jewels.”

Moreover, formal evidence suggests that demand to visit U.S. national parks—in particular the highest-profile destinations—is not sensitive to admission prices, particularly for overseas visitors. One study published in 2014 found that the price of gasoline affects national park visitation more than entry fees do.8The analysis examined 30 “major nature-based” national parks, including most of the highest-profile U.S. parks. In examining the effect of entry fees, it described demand as “very price inelastic.” Thomas H. Stevens, Thomas A. More, and Marla Markowski-Lindsay, “Declining National Park Visitation: An Economic Analysis,” Journal of Leisure Research 46, no. 2 (2014): 153-64. Another study, from 2017, estimated that raising the vehicle entry fee at Yellowstone National Park by more than double—from $30 to $70—would decrease visitation from foreign visitors by a mere 0.07 percent.9The study examined a proposal that would have raised the park’s standard vehicle entry fee from $30 to $70. The estimate of a 0.07 percent decline is for non-Canadian foreign visitors. Additionally, the study estimated that the proposed fee increase would decrease visitation from local residents of Idaho, Montana, and Wyoming by 3.0 percent and from non-local U.S. and Canadian visitors by 1.1 percent. Jeremy L. Sage et al., “Thinking Outside the Park: National Park Fee Increase Effects on Gateway Communities,” University of Montana Institute for Tourism and Recreation Research, Report 2017-11 (2017). A negligible dip would be logical given that the average overseas visitor was already spending an estimated total of $4,484 on their trip. In that context, increasing fees by a mere $40 would barely register in a traveler’s budget.

The current fee system for national parks in the United States lacks nuance, with most visitors paying a flat weekly fee that permits access for all passengers in a private vehicle.10One hundred and nine of the 425 U.S. national park units charge entrance fees. While the standard fee admits one vehicle for one week, there is a small degree of variation. For instance, the National Park Service offers an annual pass valid at all parks, offers multiple park-specific annual passes, charges different fees for visitors on foot or motorcycle, and uses a distinct fee schedule for commercial tour vehicles. National Park Service, “Your Fee Dollars at Work,” accessed October 9, 2023; National Park Service, “Entrance Fees by Park,” accessed October 9, 2023; National Park Service, “Road-based Commercial Tour CUAs,” accessed October 9, 2023. As part of this relatively blunt system, standard overseas visitors pay the same price as U.S. citizens and residents. Or put another way, locals enjoy no discount when visiting their home-nation parks. Often, Americans pay even more than foreign visitors to support national parks because, in addition to paying entry fees, most U.S. residents pay income taxes, which also partially support parks. Approximately $20 per U.S. taxpayer goes toward the National Park Service budget—each and every year, regardless of whether those Americans visit a national park.11 Given the countless factors involved in collecting and appropriating federal tax revenues, this is a very rough estimate and is meant to be illustrative. Roughly half of American households pay income taxes, depending on the year; there are about 330 million Americans; and the National Park Service budget has exceeded $3 billion in recent years. Tax Policy Center, “T21-0161 – Tax Units with Zero or Negative Income Tax, 2011-2031,” Urban Institute and Brookings Institution, August 17, 2021; Drew Desilver, “Who Pays, and Doesn’t Pay, Federal Income Taxes in the U.S.?” Pew Research Center, April 18, 2023; Laura B. Comay, “National Park Service (NPS) Appropriations: Ten-Year Trends,” Congressional Research Service, R42757 (2022). Asking overseas tourists who are not a part of the tax base to pay a little bit more to see remarkable sites in need of stewardship seems not only logical but prudent.

As many U.S. parks are facing record visitation and struggling through funding shortfalls, the idea of charging international visitors more than domestic ones has gained traction. The National Park System Advisory Board has suggested that differential pricing based on residency could be a way to increase park revenue, noting the success of that strategy in other nations.12 Rob Hotakainen, “Foreign Visitors Could Face Higher Entry Fees,” E&E News, January 8, 2021. Additionally, the late Sen. Mike Enzi (R-Wyo.) pushed in 2019 to legislatively implement a surcharge for overseas visitors to help fund national parks by raising tourist travel and visa fees by $16 and $25, respectively.13The proposal also called for the fees to be adjusted for inflation over time. Responsibly Enhancing America’s Landscapes Act, S.2783, 116th Cong. (2019); Tate Watkins, “Enhancing the Public Lands Recreation Fee System,” PERC Policy Brief (2020): 7-8.

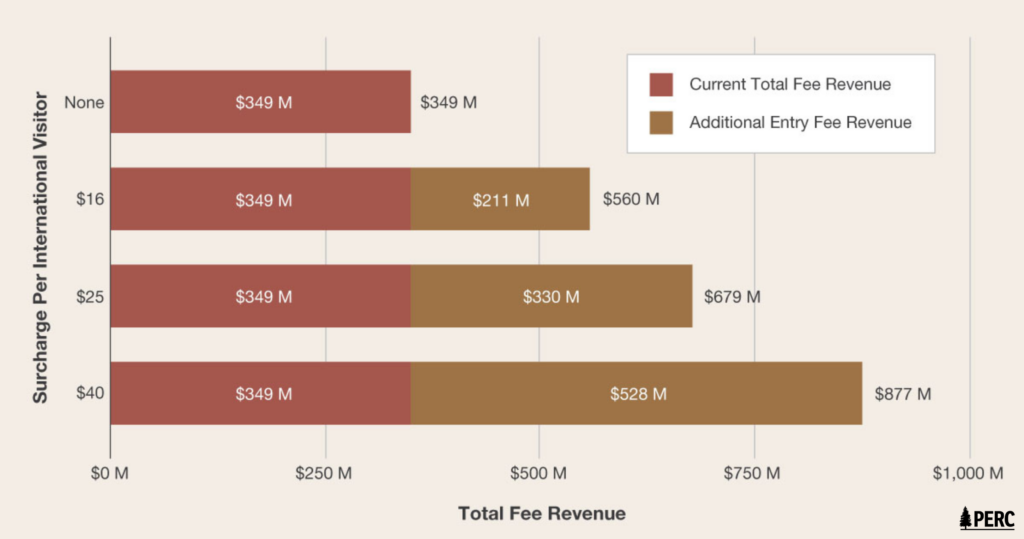

Figure 1

Scenarios for Fee Revenues with Surcharge on International Visitation

Current fee revenues across all national parks total $349 million. Under the scenarios examined, adopting a surcharge paid by each international visitor to a national park site would raise that total to an estimated $560 million to $877 million, an increase from current levels of 61 percent to 151 percent, respectively.

Note: Estimates assume that each surcharge, whether $16, $25, or $40, would decrease visitation from international tourists by 3 percent, based on existing research that demand for visitation to high-profile U.S. national parks is extremely inelastic. See, for example, Thomas H. Stevens, Thomas A. More, and Marla Markowski-Lindsay, “Declining National Park Visitation: An Economic Analysis,” Journal of Leisure Research 46, no. 2 (2014), and Jeremy L. Sage et al., “Thinking Outside the Park: National Park Fee Increase Effects on Gateway Communities,” University of Montana Institute for Tourism and Recreation Research, Report 2017-11 (2017).

Sources: National Park Service, “Fiscal Year 2024 Budget Justifications”; International Trade Administration, National Travel and Tourism Office, “Market Profile: Visit National Parks/Monuments.”

Figure 1 presents estimates for the amount of recreation fee revenue that might be raised if each international tourist who visited a national park site paid a surcharge.14 Estimates assume that each surcharge would decrease visitation from international tourists by 3 percent, based on existing research that demand for visitation to high-profile U.S. national parks is extremely inelastic, and assume that every overseas visitor who enters a national park pays the surcharge. Declining National Park Visitation, Stevens, More, and Markowski-Lindsay. Even under much more conservative assumptions, such as visitation decreases of 10 percent or more, implementing a surcharge could substantially raise total fee receipts. Scenarios include surcharges of $16 or $25, amounts equal to the increases on tourist travel and visa fees proposed in Sen. Enzi’s legislation. The third scenario is a surcharge of $40, equal to the vehicle fee increase proposed by the Department of the Interior for all visitors at the most popular parks in 2017.15National Park Service, “National Park Service Proposes Targeted Fee Increases at Parks to Address Maintenance Backlog,” News Release, October 24, 2017. Rather than implementing the proposed $40 fee increase at 17 popular parks, the agency ultimately raised fees by $5 at all parks that charge entry fees. National Park Service, “National Park Service Announces Plan to Address Infrastructure Needs & Improve Visitor Experience,” News Release, April 12, 2018. Moreover, a $40 surcharge would nearly equal the total $41 increase called for by raising both the travel and visa fees as outlined in Sen. Enzi’s bill. Current fee revenues across all parks total $349 million.16National Park Service, “Fiscal Year 2024 Budget Justifications,” RecFee-1. Implementing a surcharge on foreign visitation could raise that total to an estimated $560 million to $877 million, an increase from current levels of 60 percent to 151 percent, respectively.

“It’s great that people from all over the world recognize the value in these national treasures,” Sen. Enzi said in 2021, “but this increased visitation is adding to the maintenance backlog.” He noted that the concept is not novel: “Foreign visitors at the Taj Mahal in India will pay an $18 fee, compared to a fee of only 56 cents for local visitors. At Kruger National Park in South Africa, visitors from outside the country will pay a $25 fee per day, compared to a $6.25 fee for local visitors.”17Foreign Visitors Could Face Higher Entry Fees, Hotakainen.

The idea of differential pricing for outdoor recreation has relevant precedents elsewhere in the United States. For example, it’s standard practice for state fish and wildlife agencies to charge different prices for residents and non-residents to hunt and fish.18Dean Lueck and Dominic Parker, “The Origins and Extent of America’s First Environmental Agencies,” Working Paper (April 2023). An out-of-state visitor who wants to hunt big game in Montana, for instance, pays more than $1,200 for licenses and permits. Meanwhile, it costs a resident less than $50 in fees to hunt an elk.19Montana Fish, Wildlife, and Parks, “2023 Deer, Elk & Antelope Hunting Regulations,” (2023). Residents presumably have contributed tax dollars to help fund state agencies that manage wildlife, while non-residents have not, so significantly higher fees for non-residents increase their contribution to wildlife management. In North Carolina, non-residents pay $32 for a fishing license, double the price for residents.20North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality, “Recreational Fishing Licenses,” accessed October 30, 2023. Moreover, many states offer tiered pricing based on residency to visit state parks and campgrounds, often charging about $10 more per night.21Holly Fretwell and Kimberly Frost, “State Parks’ Progress Toward Self-Sufficiency,” Property and Environment Research Center (2006); Sara Sheehy, “These State Parks Charge More for Out-of-State Campers,” Campendium, January 21, 2022.

Whether differential pricing were implemented directly at park gates or indirectly through other means, it could significantly increase total resources available to maintain sites and serve visitors. Implementing a surcharge for overseas visitors would boost revenue from a set of people able and willing to pay it, allowing parks to better meet their basic needs and come closer to funding maintenance in a sustainable way.

The Blessing and Curse of Visitation

Excluding declines during the Covid-19 pandemic, visitation to U.S. national parks has steadily increased over the past decade. In recent years, more than 300 million people have consistently visited parks annually.22From the late 1980s to the mid-2010s, visitation to U.S. national parks was relatively flat. Total visits never exceeded 300 million until they reached 307 million in 2015. Visitation surpassed 330 million in 2016 and 2017, was 327 million in 2019, and then fell by more than one-quarter during the Covid-19 pandemic. By 2022, visitation had rebounded to more than 311 million visits. National Park Service, “Visitation Numbers,” accessed October 16, 2023. More visitors to parks, however, impose more costs on infrastructure and assets. These range from wear and tear on roads, trails, and campgrounds to increased pressure on wastewater systems to neglected employee housing. The demands on park resources have outpaced the budgets available to manage them. After adjusting for inflation, the National Park Service’s discretionary budget has remained stagnant for years.23How We Pay to Play, Watkins.

The current backlog of overdue maintenance for park infrastructure is estimated at $22 billion.24By the Numbers, NPS. This includes more than $5 billion in paved road repairs, $1 billion in water system improvements, and $900 million for trails and campgrounds. Specific repairs include fixing wastewater treatment facilities near Yellowstone’s Old Faithful, rehabilitating 20 bridges in Acadia National Park, improving campground bathrooms in Yosemite, and resurfacing portions of Skyline Drive in Shenandoah National Park.25National Park Service, “Identifying & Reporting Deferred Maintenance,” National Park Fact Sheets as of the end of FY2022, accessed October 16, 2023. These overdue projects are in addition to the day-to-day maintenance needed to keep all national parks open and accessible to visitors.26Tate Watkins, “Fixing National Park Maintenance For the Long Haul,” PERC Policy Brief (2020).

In light of funding challenges, visitor fees are an important and growing source of revenue for many parks. Across all federal land management agencies, recreation fee revenues increased by 40 percent over the five years leading up to the pandemic.27Carol Hardy Vincent et al., “Effect of COVID-19 on Federal Land Revenues,” Congressional Research Service, R46448 (2020). Recreation fee receipts for national parks now total nearly $350 million annually, an amount roughly equivalent to 10 percent of the park system’s discretionary budget.28Fiscal Year 2024 Budget Justifications,” NPS, RecFee-1; NPS Appropriations, Comay. The distribution of this fee revenue varies greatly. Some parks charge no fees and therefore have no fee revenue. By contrast, several high-profile national parks have in some years generated more revenue through fees than they received in congressional appropriations.29Enhancing the Public Lands Recreation Fee System, Watkins, 4.

The structure of the recreation fee system means that supplemental funding from fees helps mitigate the impacts of visitation. Passed in 2004, the Federal Lands Recreation Enhancement Act not only allows parks to charge fees, it also permits them to retain and spend up to 80 percent of receipts where they are collected. Before the act became law, receipts from visitor fees were sent to the federal treasury.30Enhancing the Public Lands Recreation Fee System, Watkins.

Because parks can spend the revenues they generate from fees, the decision-making authority over those revenues remains with superintendents and staff managing recreation sites on the ground. The model empowers local staff, rather than far-away bureaucrats or politicians, to decide how to best serve their own visitors. It also removes some of the political influence over spending decisions.

Local managers who serve users well and improve the visitor experience can benefit directly if their efforts increase fee revenues. Relatedly, managers have better knowledge about site operations and on-the-ground priorities than appropriators, so allowing them to make decisions about where to spend revenues is prudent. Channeling visitor fee revenues into park budgets also means that the people who benefit the most from parks directly invest in stewarding them.

Refining a Blunt Instrument

Of the 425 sites administered by the National Park Service, 109 charge entry fees.31Your Fee Dollars at Work, NPS. In addition, many parks charge fees for the use of various amenities such as campsites, day-use areas, and cabins. The agency is subject to various legislative stipulations that govern where, how, and for whom recreation fees can be levied.32Enhancing the Public Lands Recreation Fee System, Watkins.

Spiraling maintenance needs and funding shortfalls have prompted a search for new and better ways to sustain parks, including by tapping park visitors to play a larger role in helping parks flourish. The current fee system offers various opportunities for refinement. Examples include charging by day rather than week, charging by person rather than vehicle, or using shoulder-season or weekday discounts to raise off-peak revenue.

One of the most straightforward options to refine the fee system is to add an entrance surcharge for international visitors. As described above, this option could raise a meaningful amount of revenue to support the National Park Service. Implementing an entry surcharge for every international tourist who visits a U.S. park could raise significant funding dedicated to stewarding parks (see Figure 1). Under certain assumptions, a surcharge might double total recreation fee revenues.33This rough estimate is meant to be illustrative and assumes that the surcharge would decrease visitation from international tourists by 3 percent, a reasonable starting point for analysis. One recent study estimated that more than doubling the vehicle entry fee at Yellowstone National Park, from $30 to $70, would decrease visitation from non-Canadian foreign visitors by less than one percentage point. Thinking Outside the Park, Sage et al.

Tiered pricing for entry holds enormous potential especially for the most popular parks.34National park entry fees do not just benefit the parks in which they are collected. Under the current law, up to 80 percent of fees are required to be spent in the park in which they were collected, while the remaining 20 percent are used park-system wide. In this way, increased fee revenues in popular parks not only benefit those parks, but also benefit other units in the national park system. For more details see Enhancing the Public Lands Recreation Fee System, Watkins. The U.S. national parks often featured in art prints and wall calendars—Zion, Acadia, the Everglades, Grand Teton, and the like—not only attract many international visitors but have also strained greatest under the stress of surging visitation.35National Park Service, “Most Famous National Parks Set Visitation Records in 2021,” News Release, February 16, 2022; Annette McGivney, “‘Everyone Came at Once’: America’s National Parks Reckon with Record-Smashing Year,” The Guardian, January 1, 2022; National Parks Are Overcrowded, Pohle; Crowded National Parks Have Turned to Reservations, Pohle. For instance, past surveys suggest that as many as one-quarter of summer visitors to Yosemite National Park have come from abroad.36National Park Service, “Park Statistics,” Yosemite National Park, accessed October 23, 2023. Similarly, Grand Canyon National Park’s superintendent has estimated that, in a normal year, 30 to 40 percent of visitors come from other countries.37Victoria Hill and Faith Abercrombie, “Lack of International Travelers Keeps Grand Canyon Visitor Numbers Down,” The Daily Yonder, July 29, 2021. Both parks have felt the stress of growing visitation: Yosemite has the second-highest total of overdue maintenance in the entire park system, at $1.1 billion; Grand Canyon is fifth, with $829 million.38Identifying & Reporting Deferred Maintenance, NPS.

At Yellowstone National Park, a modest surcharge on overseas visitation would likely double revenues from gate fees, while a higher one could triple current receipts. Surveys during summer 2018 suggested that perhaps 20 percent of Yellowstone visitors did not permanently reside in the United States.39Surveys were carried out during portions of the months of May to September. National Park Service, “Yellowstone National Park Summer 2018 Visitor Use Surveys,” Final Report (2019): 14. Summer visitation that year surpassed 3.7 million.40Includes visits from May to September. National Park Service, “Recreation Visits by Month: Yellowstone NP,” National Park Service Visitor Use Statistics, accessed October 16 2023. A $16 entry surcharge for each international visitor—an amount equal to the additional tourist travel fee proposed by Sen. Enzi—could have raised an estimated $9.3 million that summer. A surcharge of $40 might have raised $23.3 million.41Total estimated collections for a $16 and $40 surcharge would have equaled $11.6 million and $29.0 million, respectively. Scenarios assume 80 percent of revenue would have been retained by Yellowstone and 20 percent apportioned to other parks in the system. Estimates assume that each surcharge would decrease visitation from international tourists by 3 percent, a reasonable assumption given existing evidence. Thinking Outside the Park, Sage et al. Because the estimates are only applied to the surveyed months of summer visitation (May to September), they potentially underestimate the amount of revenue that would be raised over an entire year. Those sums would be on top of the park’s current entrance fee revenue of roughly $9.1 million, meaning the scenarios examined could grow the park’s total receipts from entry fees to an estimated $18.4 million to $32.3 million.42National Park Service, “Yellowstone National Park: State of the Park 2023,” (2023). Entrance fee receipts retained by Yellowstone equaled approximately $9.1 million per year over the previous five years. A surcharge would also support the wider park system by raising an estimated $2.3 million to $5.8 million to be distributed to other parks that do not charge fees.43Under the current law, up to 80 percent of fees are required to be spent in the park in which they were collected, while the remaining 20 percent are used park-system wide. In this way, increased fee revenues in popular parks not only benefit those parks, but also benefit other units in the national park system. For more details see Enhancing the Public Lands Recreation Fee System, Watkins.

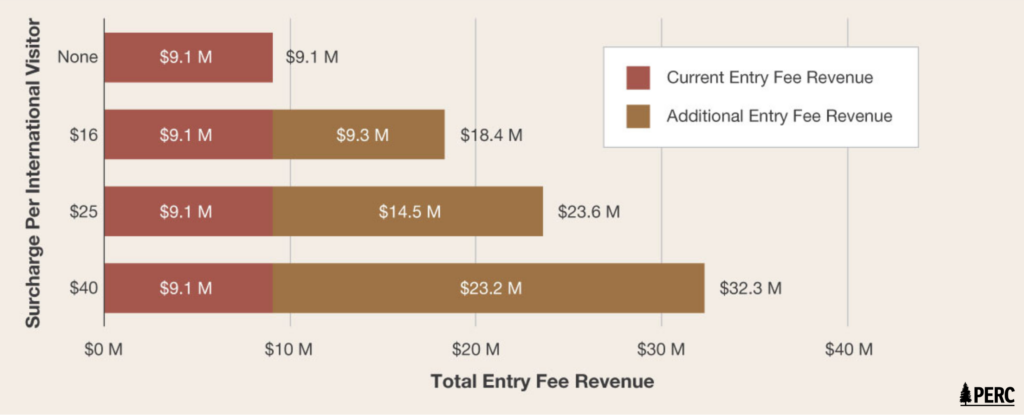

Figure 2

Scenarios for Yellowstone National Park Entry Fee Revenue with Surcharge on International Visitors

Current entry fee revenues at Yellowstone National Park are estimated to be $9.1 million. Under the scenarios examined, the park’s receipts from entry fees would rise to an estimated $18.4 million to $32.3 million by increasing prices for international visitors.

Note: The scenarios displayed assume that 80 percent of additional receipts would be retained by Yellowstone. Twenty percent of total revenue raised from a surcharge would support the wider park system by being distributed to parks that do not charge fees. These totals, not pictured above, are estimated to range from $2.3 million to $5.8 million under the scenarios examined. Estimates assume that each surcharge, whether $16, $25, or $40, would decrease visitation from international tourists by 3 percent, based on research that demand for visitation to Yellowstone National Park is extremely inelastic. Jeremy L. Sage et al., “Thinking Outside the Park: National Park Fee Increase Effects on Gateway Communities,” University of Montana Institute for Tourism and Recreation Research, Report 2017-11 (2017).

Sources: National Park Service, “Yellowstone National Park: State of the Park 2023″; National Park Service, “Yellowstone National Park Summer 2018 Visitor Use Surveys,” Final Report (2019); National Park Service, “Recreation Visits by Month: Yellowstone NP,” National Park Service Visitor Use Statistics.

Looking Abroad

Charging foreign tourists higher fees than citizens is common at national parks in many countries. Foreign tourists to the Galapagos Islands, for instance, pay a flat fee of $100, while Ecuadorian citizens pay $6.44Parque Nacional Galápagos, “Tributo de Ingreso,” accessed October 16, 2023. At South Africa’s iconic Kruger National Park, renowned for its lions, leopards, elephants, and other charismatic African wildlife, international visitors pay about $25 per day, while residents pay about $6.45Kruger National Park “Tariffs: Daily Conservation Fees,” accessed October 16, 2023. Torres del Paine National Park, in the Chilean Patagonia, charges foreigners $55 for extended visits, almost four times the $14 that citizens pay.46Parque Nacional Torres del Paine “Tarifas a Partir del 1 de Enero de 2024,” accessed October 16, 2023. And Nepal’s Chitwan National Park, home to rhinos, tigers, gharial crocodiles, and more than 500 species of birds, charges foreign visitors $15 per day, while locals pay just over $1.47Nepal Tourism Board, “Entry Fees for Sites in Chitwan,” accessed October 16, 2023.

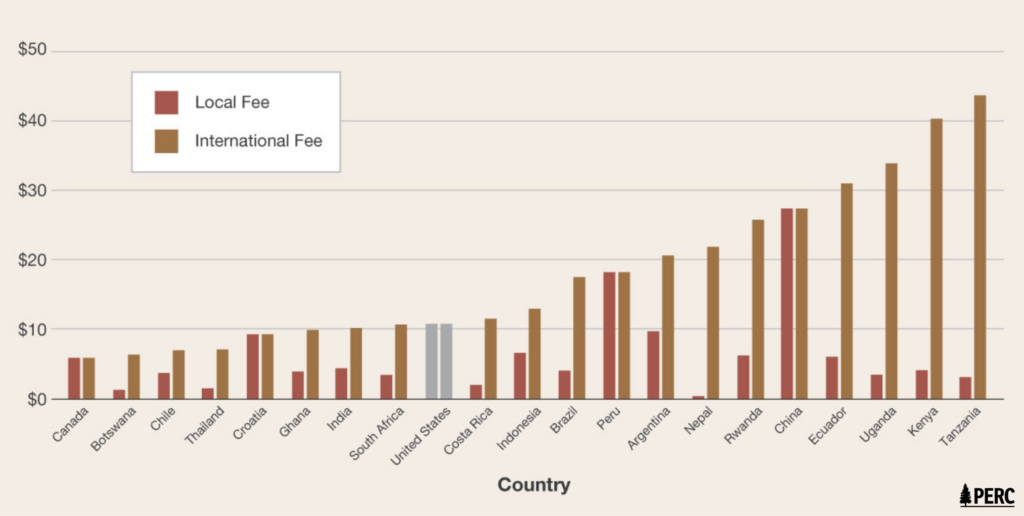

A 2019 report that reviewed entry fees at national parks around the world found approximately three dozen nations that charge non-citizens more than citizens.48National Park Entrance Fees, Van Zyl, Kinghorn, and Emerton. The strategy allows park systems to benefit from foreign visitors’ ability and willingness to pay, particularly in relatively lower-income countries. Additionally, for countries that receive a high share of visits from international tourists, the approach ensures that taxpayers do not bear an outsized burden of funding those visits. Many park systems explicitly state that fee revenue is dedicated to funding operations and stewarding natural resources in parks. Figure 3 displays fees paid by local and international visitors to national parks in selected countries, including the United States.49Table 1 in the Appendix provides a full list of local and international entry fees for countries included in the report.

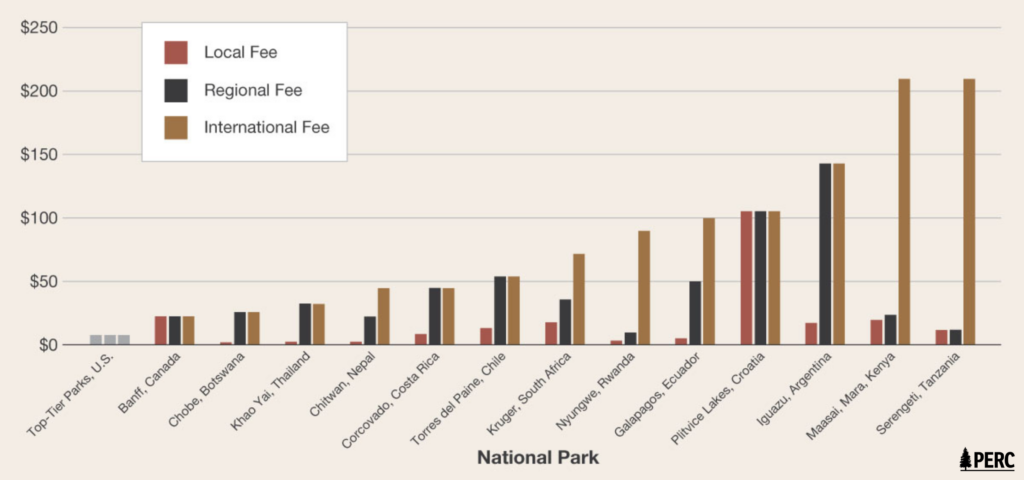

Figure 3

Average National Park Entry Fees for Selected Countries

Many of the world’s most high-profile national park systems charge overseas visitors more than locals.

Note: Fees are expressed in U.S. dollars, per person, per day and use an unweighted average for each country, as reported in “National Park Entrance Fees: A Global Benchmarking Focused on Affordability.” Local fee is the entry price paid by a country’s own citizens. International fee is the entry price paid by foreign tourists.

Source: Hugo Van Zyl, James Kinghorn, and Lucy Emerton, “National Park Entrance Fees: A Global Benchmarking Focused on Affordability,” Parks 25, no. 1 (2019).

Some national park systems have adopted fee schedules with several tiers. At various parks, citizens of nearby countries pay a higher price than locals but a lower one than foreigners from farther away. Tourists to the Galapagos Islands from nearby countries, for instance, pay half as much as other foreigners.50Tributo de Ingreso, Parque Nacional Galápagos. A chimpanzee trek at Nyungwe National Park costs foreign visitors from the East Africa Community $10, more than the $4 Rwandans pay but much less than the $90 fee for other international tourists. Citizens of nations in the Southern African Development Community, a regional trade bloc, pay half the price of other internationals at South Africa’s national parks.51Tariffs: Daily Conservation Fees, Kruger National Park.

Figure 4 shows fee tiers per person at selected parks around the world for a three-day visit. Fees for international tourists are by far lower at U.S. parks than at the other parks analyzed. The standard entry fee at top-tier U.S. national parks is $35 per vehicle for up to one week, meaning that each member in a family of four would cost less than $9.52Even for a family of two, the per person entry fee for a three-day visit to U.S. national parks would be less than $18, far less than fees at many other popular national parks around the world. At Banff National Park in Canada, which does not differentiate between local and international visitors, three days of entry costs about $23. Three-day visits for international tourists at Chitwan in Nepal or Corcovado in Costa Rica would each cost roughly $45. Plitvice Lakes National Park, in Croatia, would cost all visitors about $106, while foreigners visiting Iguazu Falls and the flora and fauna around it in Argentina would pay about $143. National parks and reserves in East Africa consistently have some of the priciest entry fees. International tourists to Maasai Mara in Kenya or Serengeti National Park in Tanzania pay $70 per day, making it $210 for three days of admission.

Figure 4

Entry Fees for Three-Day Visit to Selected National Parks

Many iconic national parks around the world charge different prices for visitors from different places. Fees for international tourists are by far lower at U.S. parks than at the other parks analyzed.

Note: Fees are expressed in U.S. dollars and estimated per person for a three-day visit. Local fee is the entry price paid by a country’s own citizens. Regional fee, if lower than the international fee, is a discounted entry price paid by visitors from nearby countries, often members of a trade bloc or regional community. International fee is the entry price paid by all other foreign tourists. U.S. per person fee estimated for a family of four. Nyungwe fee is a flat fee for a chimpanzee trek. Galapagos fee is a flat fee for entry to the islands. Plitvice Lakes and Iguazu fees include second-day discounts.

Sources: National park and tour operator websites.

For full details and sources, see Table 2 in the Appendix

Approaches vary when it comes to collecting entry fees from overseas visitors. Many national parks charge at the gate and require local identification to receive the local price. Other sites, particularly islands, charge tourists upon airport arrival or departure. When visitors arrive at one of the two Galapagos Islands airports, for instance, park rangers collect the entrance fee for tourists.53Tributo de Ingreso, Parque Nacional Galápagos. Some national park systems rely on tour operators or guides to assist with fee collection.

Alternatively, some nations have chosen to levy indirect fees that are dedicated to park stewardship or natural resource management more generally. These conservation fees are collected in various ways, including at port of entry or exit, as part of airfare purchases, through hospitality taxes, or as part of visa fees.54Emelia von Saltza and John N. Kittinger, “Financing Conservation at Scale via Visitor Green Fees,” Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution 20 (2022). Belize, for instance, charges foreign tourists a $20 departure fee when leaving the country and dedicates the proceeds to conservation.55James F. Casey and Peter W. Schuhmann, “PACT or No PACT Are Tourists Willing to Contribute to the Protected Areas Conservation Trust in Order to Enhance Marine Resource Conservation in Belize?” Marine Policy 101 (2019): 8-14. The Maldives assess a $6 per day “green tax” on tourists from abroad, levied through hotel fees.56Maldives Inland Revenue Authority, “Green Tax,” accessed October 23, 2023. Most foreign tourists visiting New Zealand pay an “international visitor conservation and tourism levy,” purchased online, that is equivalent to about $20.57New Zealand Immigration, “Paying the International Visitor Conservation and Tourism Levy (IVL),” accessed October 23, 2023.

The lack of nuance in differentiating fees at U.S. national parks results in illogical structures when compared to high-profile parks around the world that also charge for entry. A European family visiting Zion National Park for three days, for instance, would pay $35 for a week-long visit. That would be nearly equivalent to the roughly $28 that a Kenyan family of four would pay to visit their home-country wildlife reserve of Maasai Mara for just a single day. When compared to global peers, there is clearly a great opportunity to refine the fee structures at U.S. parks in ways that would raise funds dedicated to their stewardship.

Recommendations

Authorize park superintendents to implement a surcharge on international visitors.

The National Park Service should authorize superintendents to adopt a surcharge that can raise dedicated funds to improve stewardship. Park superintendents are well positioned to know whether adopting a surcharge makes sense at their individual units. The bulk of revenue from a surcharge would likely come from the few dozen major national parks that are least sensitive to price and have significant numbers of international visitors.

When it comes to setting the level of a surcharge, one option would be for the National Park Service to suggest appropriate tiers for certain groupings of parks, similar to existing entry fee tiers. Then park superintendents could decide whether to implement the relevant international surcharge at their park. A degree of regional coordination could optimize fee structures by ensuring prices are harmonized across comparable parks. Superintendents from Utah’s “Mighty 5” parks, for instance, may find it worthwhile to coordinate pricing.58Utah Office of Tourism, “The Mighty 5,” accessed November 8, 2023. But leaving the decision to adopt a surcharge largely up to local park staff would empower them to decide whether tiered pricing makes sense at their site.

Amend the Federal Lands Recreation Enhancement Act to explicitly permit national parks to differentiate fee pricing.

While the enabling legislation for the fee system does not prohibit differentiation in pricing, Congress should act to make that authority clear. Past agency actions regarding national park fees—including decisions to use fee collections to keep parks open during government shutdowns and proposals to raise entry fees—have led to public disputes.59J. Weston Phippen, “Keeping the National Parks Open Is a Terrible Idea,” Outside, May 12, 2022; Darryl Fears, “Public Outrage Forces Interior to Scrap Massive Increase in Park Entry Fees,” The Washington Post, April 12, 2018. By explicitly permitting national parks to differentiate fees, including by place of origin, policymakers would avoid any potential uncertainty over the reform. Furthermore, a clear signal from Congress could encourage parks to adopt a surcharge on international visitation and may even motivate them to pilot additional innovations for the fee system. Advance reservations that avoid congestion at park gates, experiments with per person or shoulder season pricing, and numerous other creative ideas stand to benefit parks by smoothing the visitor experience and growing dedicated funding streams.

Study challenges of and solutions to implementing tiered pricing for overseas visitors to determine the optimal approach.

To be sure, there are various ways a surcharge could be implemented and multiple important factors to consider. Park superintendents should study several options for exactly how to implement a surcharge, including the challenges inherent to each and ways to overcome them. Clearly, there are many factors to consider when weighing whether or how to implement a surcharge on international visitation. The sizable amount of revenue that could be raised at high-profile parks, however, would motivate a search for solutions that overcome the challenges.

Experiment with different approaches for collecting the surcharge at individual parks.

Incorporating a surcharge as part of entry fees has advantages over alternatives, but it presents logistical challenges. Park superintendents should experiment with different ways to collect the surcharge. Importantly, making a surcharge part of entry fees would mean the majority of receipts would be retained where collected, preserving the sound incentives of the current fee system. Charging each individual overseas tourist, however, as this brief suggests, presents a challenge given that many visitors currently pay park entry fees per vehicle.

International travelers typically plan trips well in advance. Parks could take advantage of this reality by having an entry-fee surcharge paid electronically in advance of arrival and implementing a straightforward way to display prepayment upon entry.60If national parks cannot retain and spend the majority of the proceeds of entry fees paid online, then an electronic system will undermine the positive feedback loop of fees funding improved visitor services. To retain these sound incentives, the National Park Service should implement a way to track electronic sales at the park level and remit the majority of receipts to those parks, as happens for fees collected at park gates. In recent years, parks such as Grand Canyon have abandoned selling digital passes online as a way “to keep more visitor fees in the park to improve the visitor experience.” National Park Service, “Fees & Passes,” Grand Canyon National Park, accessed November 9 2023. Alternatively, to avoid congestion concerns, parks could leave collection or enforcement of the surcharge to some point beyond physical gates, similar to how some state parks check passes in parking or other areas.61Another option to motivate advance payment aimed at smoothing entrance congestion, parks could consider offering a discount for prepayment, although this approach would affect revenue estimates. Relatedly, the fact that many international tourists visit national parks via tour buses could make implementation simple if it allows for coordination of payment with or even remittance of fees from commercial operators.62Notably, some commercial vehicle passes already incorporate per person charges. Road-based Commercial Tour CUAs, NPS.

Another factor to consider is how Americans demonstrate they qualify for the local price. One approach would be to mimic the way hunting and fishing licenses are sold, whereby receiving the resident price could depend on having state-issued identification. Ideally, this could also be done in advance of arrival through electronic purchasing systems. Buying park entry passes online already often entails providing some sort of identifying information, such as a license plate number.

Separate the surcharge on international visitation from annual passes.

The National Park Service should harmonize any surcharge with its annual pass framework. One option would be to offer annual passes to residents only. Another would be to make annual passes available to international tourists but still levy a surcharge per individual visit. Regardless of the exact details, harmonizing implementation within existing fee structures would ensure the overall effectiveness of an international-pricing strategy.

If the surcharge is collected indirectly, distribute the revenue based on international visitation and empower park superintendents to use the receipts.

Bundling a surcharge as part of visa or travel fees, such as legislation previously sponsored by Sen. Enzi proposed, could overcome administrative concerns related to collection; however, it would also flatten important incentives built into the current fee system. The positive feedback loop created by devoting the majority of fee receipts to the site of collection is an important characteristic that would ideally be maintained and magnified through the adoption of a surcharge.

If Congress decides to collect an international surcharge through visa fees or another indirect mechanism, then the revenue should be distributed to parks based on foreign visitation.63This would entail administrative and logistical challenges of its own given that parks do not currently track or estimate foreign visitation in a systematic way. Relatedly, park superintendents should have the same authority and flexibility to spend those funds as they do for entrance fees.

While increasing visa or travel fees could conceivably raise more revenue than directly raising entry fees would—given that even tourists who do not visit national parks would pay them—it would leave open the question of how to spend receipts. Sen. Enzi’s bill proposed to give the interior secretary ultimate authority over spending funds, with various stipulations resembling the framework of the Legacy Restoration Fund that was created by the Great American Outdoors Act.64Responsibly Enhancing America’s Landscapes Act, S.2783, 116th Cong. (2019); The Great American Outdoors Act, Public Law 116–152, 116th Cong. (2020). Such a spending framework could provide a guide. But it would be inferior to a mechanism that empowers superintendents to make local decisions about how to best serve visitors and care for park resources.

Conclusion

The U.S. park system includes some of the most popular national parks in the world. Our parks clearly need help to ensure they can sustain the impacts of increasing visitation, including from visitors from abroad. Recreation fees provide an important and growing revenue stream for many national parks, and charging higher fees for overseas visitors could significantly grow current fee receipts.

The “crown jewel” parks most popular with international tourists stand to benefit the most from refining current fee structures. The point of charging more for visitors from abroad is not to squeeze them as much as possible; rather, it’s to harness the enthusiasm for and interest in our nation’s remarkable wonders to provide resources that will allow them to be stewarded properly.

Dozens of countries around the world have set the precedent of charging foreign tourists more to visit national parks than citizens. Adopting the approach in the United States would provide much-needed funding to make sure the U.S. park system can be sustained for visitors of all types for generations to come.