Introduction

Wild horses and burros are icons of the American West. But without predators, herds can double in size every four years.1BLM, “Wild Horse and Burro Program: Fiscal Year 2023,” Fact Sheet. Their increasing populations on public rangelands put tremendous pressure on ecosystems by degrading forage and soil, damaging riparian areas, competing with other wildlife, and imperiling endangered and threatened species.

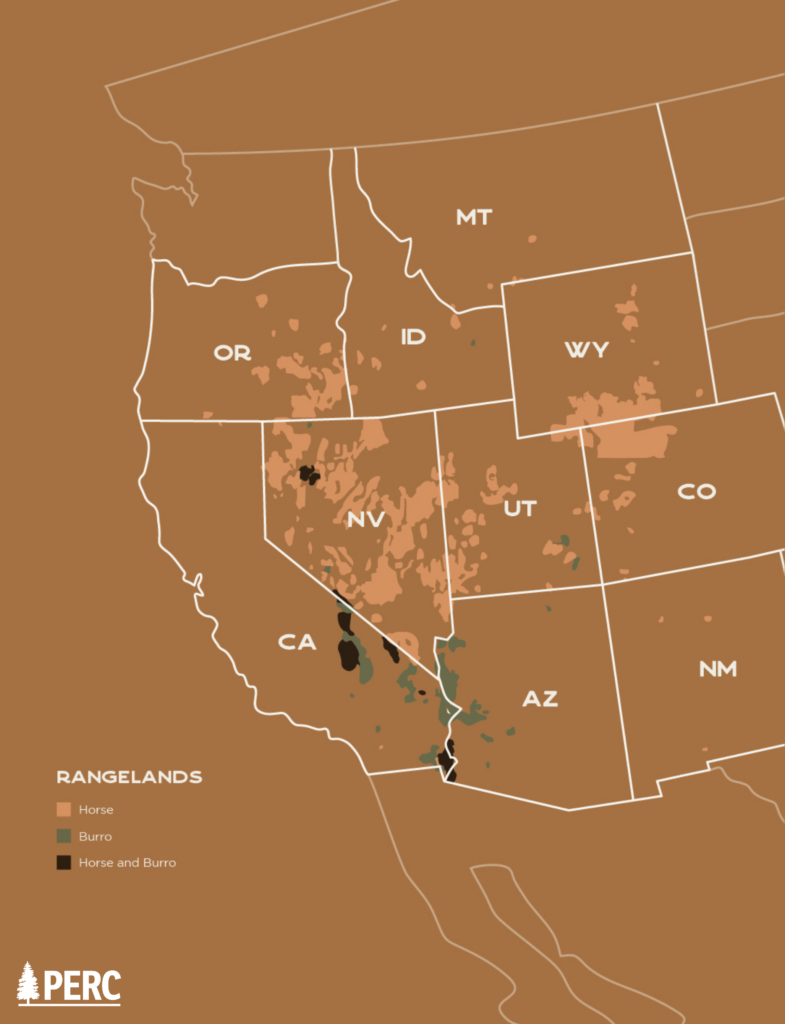

The Wild Free-Roaming Horses and Burros Act of 1971 authorized and directed the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) to manage the wild equines by establishing sustainable population goals and gathering and removing excess animals.2The U.S. Forest Service also manages a relatively small number of wild horses; most attention has focused on the BLM given that it manages the vast majority of the animals. The agency manages 177 herds of wild horses and burros on 27 million acres in 10 western states, and it sets target population thresholds for each herd.3BLM, “Wild Horse and Burro Program,” accessed February 5, 2024.

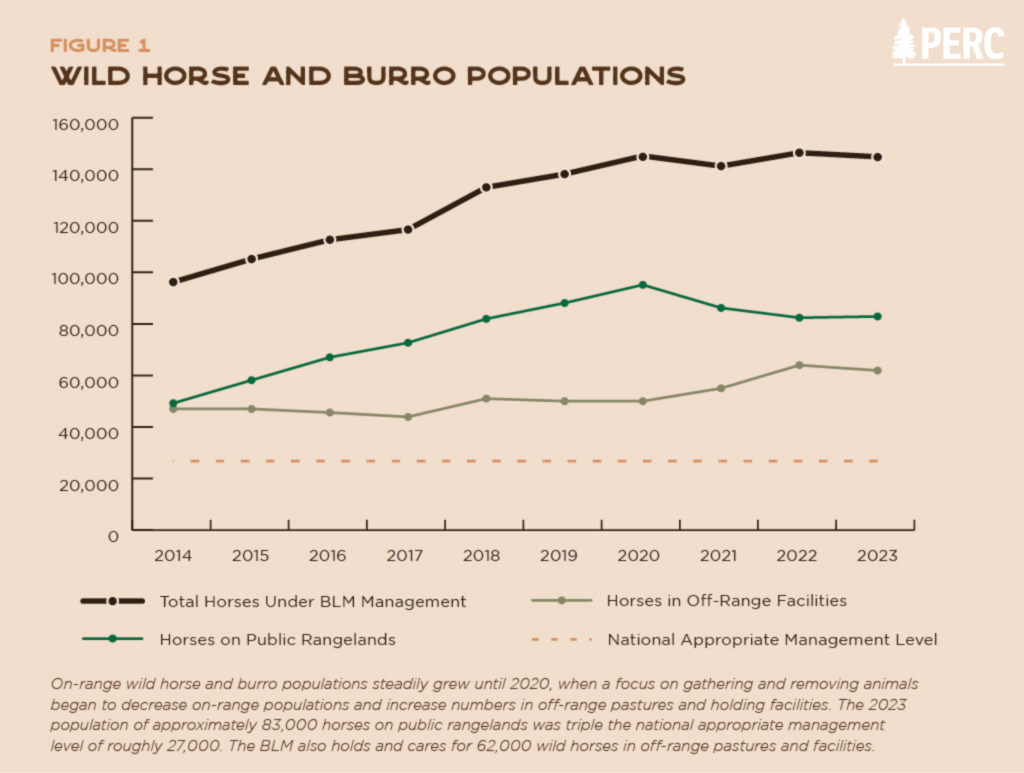

The number of wild horses on BLM lands has reached unsustainable levels, threatening rangeland ecosystems across the western United States and at times risking death by starvation or thirst for the animals themselves. Of the 177 individual herds, 152 are overpopulated. The total estimated population of 83,000 animals on public lands in 2023 was triple the national estimated sustainable threshold of 27,000.4BLM, Wild Horse and Burro Program: Fiscal Year 2023. In March 2024, the agency released a new population estimate of approximately 73,000 wild horses and burros on public rangelands—a decrease from the previous year yet still far above the sustainable threshold.5BLM, “BLM 2024 Wild Horse and Burro Estimates Show Reduced Overpopulation,” News Release, March 25, 2024. The BLM holds and cares for animals that it has removed from public lands. Currently, the agency houses 62,000 wild horses in off-range pastures and facilities, costing taxpayers $108.5 million in 2023.6BLM, “Program Data,” Wild Horse and Burro Program, accessed December 1, 2023. The total wild horse population, including animals on and off public rangeland, has reached nearly 145,000.

The number of wild horses on BLM lands has reached unsustainable levels, threatening rangeland ecosystems across the western United States and at times risking death by starvation or thirst for the animals themselves.

Because they are feral, wild horses are neither livestock managed privately nor game managed by state wildlife agencies. Their unique status presents a singular management challenge for the BLM. On the one hand, the cost of continually removing wild horses from public rangelands and caring for them in holding facilities is “both economically unsustainable and discordant with public expectations,” as an analysis by the National Research Council has summarized it. On the other hand, as the analysis continued, “the consequences of simply letting horse populations, which increase at a mean annual rate approaching 20 percent, expand to the level of ‘self-limitation’—bringing suffering and death due to disease, dehydration, and starvation accompanied by degradation of the land—are also unacceptable.”7National Research Council, Using Science to Improve the BLM Wild Horse and Burro Program: A Way Forward, Committee to Review the Bureau of Land Management Wild Horse and Burro Management Program, Board on Agriculture and Natural Resources, Division on Earth and Life Studies (Washington, D.C.: The National Academies Press, 2013), vii.

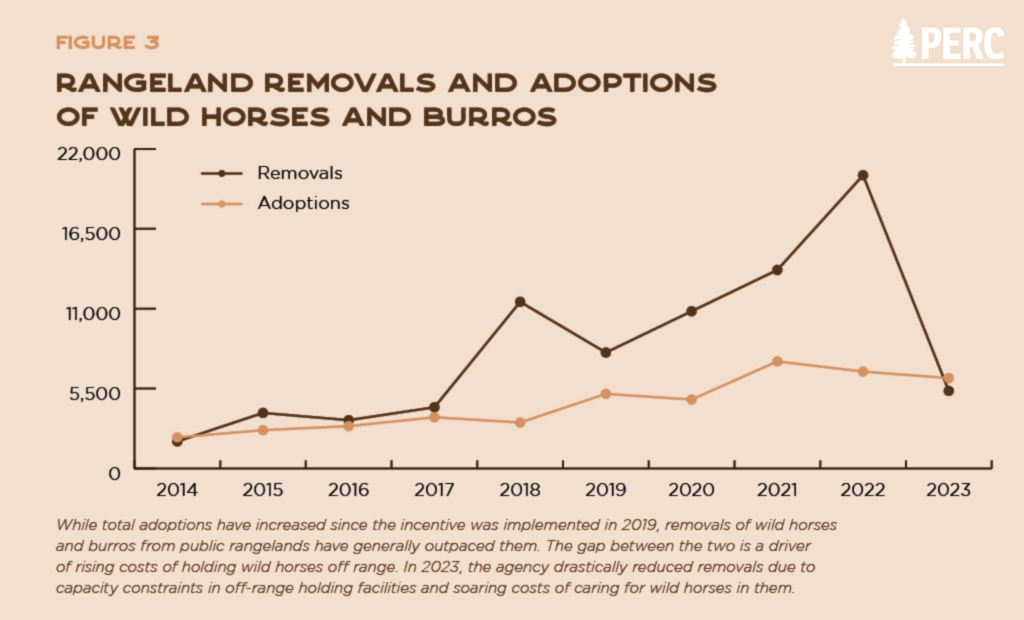

Ultimately, to relieve the pressures on public land ecosystems, horses must leave the range and BLM care faster than they repopulate. The primary way that horses leave BLM care is through adoption into private homes. In an effort to increase adoptions of wild horses and burros and ease the burden on rangelands and taxpayers, in 2019 the agency established a financial incentive for adopters of these animals.

This report analyzes the BLM’s adoption incentive program in the context of the wild horse population crisis, evaluating the effectiveness of this initiative. It finds that average annual adoptions of wild horses and burros have more than doubled in the five years since the inception of a $1,000 adoption incentive in 2019 compared to the previous five years.8Adoptions are reported by fiscal year, and references to figures for a given year in this report generally refer to fiscal years. It also finds that the 15,000 adoptions facilitated by the program have already saved the BLM and taxpayers approximately $66 million in avoided holding costs and will save $400 million over the lifetime of those adopted wild horses and burros. The program is on track to place more than 30,000 animals in private homes over its first decade and save more than $800 million in lifetime costs. The report concludes by offering several recommendations for the future of the wild horse and burro program.

Highlights

Growing populations of wild horses and burros threaten rangeland ecosystems across the western United States. The current total population of 73,000 animals on public land is nearly triple the national estimated sustainable threshold of 27,000.

In addition, the Bureau of Land Management holds and cares for 62,000 wild horses in off-range pastures and facilities, costing taxpayers $108.5 million in 2023.

Average annual adoptions of wild horses and burros have more than doubled in the five years since the inception of a $1,000 adoption incentive compared to the previous five years. The lifetime cost savings of adopting a wild horse into private care is estimated to be between $22,500 and $29,000.

Since the incentive program was implemented in 2019, the BLM and taxpayers have already saved approximately $66 million in avoided holding costs. The more than 15,000 incentive adoptions to date will save approximately $400 million over the lifetime of those wild horses and burros. The program is on track to place more than 30,000 animals in private homes over its first decade and save more than $800 million in lifetime costs.

Ultimately, the rate of placing wild horses and burros into private care must exceed the rate at which the animals repopulate on public lands. The adoption incentive program is one effective tool that can help relieve stress on public rangelands and promote fiscal sustainability over the long term.

Background

The wild horses and burros that roam the western United States today were first introduced by Spanish settlers in the early 1500s.9Prehistoric fossil evidence suggests that horses existed on the North American continent prior to the last Ice Age. Florida Museum, “Fossil Horses Online Exhibit,” accessed January 10, 2024. Eventually, escaped domestic animals established feral populations of horses and burros.10Feral donkeys and mules are generally known as burros. Wild horses are also referred to as mustangs. By the 19th century, wild horses had proliferated across parts of the western United States, although reliable population figures are lacking.11Writer Frank Dobie, for instance, noted in 1952: “No scientific estimate of their numbers was made. … All guessed numbers are mournful to history. My own guess is that at no time were there more than a million mustangs in Texas and no more than a million others scattered over the remainder of the West.” J. Frank Dobie, The Mustangs (Little Brown and Company: New York, 1952) 108-09.

By the 1970s, however, populations had declined, to an estimated 17,000 horses, as over a million wild equines had been conscripted for World War I, and killing the animals for industrial uses or through hunting for sport were also common.12Utah State University Extension, “TimeLine: A Chronology of Free-Roaming Equids,” Free Roaming Equids and Ecosystem Sustainability Network, accessed January 10, 2024. Amid outcry to protect the wild horses and burros, the Wild Free-Roaming Horses and Burros Act of 1971 tasked the Bureau of Land Management with managing the animals by establishing sustainable population goals, deemed “appropriate management levels,” and removing excess animals from public rangelands.13Wild Free-Roaming Horses and Burros Act of 1971, Public Law 92-195, 92nd Cong. (1971) (as amended). For decades, Congress has prohibited use of agency funds for sales of wild horses and burros that result in slaughter or processing into commercial products of any type.14Vincent, Wild Horse and Burro Management, 1.

Federal protection has been successful in reversing the past decline of wild horse and burro populations, but populations have now grown to levels that the BLM considers unsustainable. Because the animals have no predators, their populations increase by roughly 20 percent annually unless actively managed, stressing ecosystems.15Tim Fitzgerald and Randy Rucker, “You Can’t Drag Them Away,” PERC Reports 36, no. 1 (2017). In exceptional cases, mountain lions may prey on wild horses in specific areas. National Research Council, Using Science to Improve the BLM Wild Horse and Burro Program, 73. In 2020, wild horse and burro populations on public rangelands peaked at nearly four times the national appropriate management level.

In some herds, spiraling populations combined with on-range conditions have led to life-threatening circumstances. During a 2018 drought, nearly 200 wild horses died of dehydration on the Navajo Nation in Arizona.16CBS/AP, “Nearly 200 Horses Found Dead Amid Southwest Drought in Arizona,” May 6, 2018. In 2021, half of the horses and burros removed by the BLM were facing emergency threats to their well-being, predominantly drought.17BLM, “Wild Horse and Burro Program: Highlights from Fiscal Year 2021,” Fact Sheet; BLM, “BLM Prepares for Emergency Action to Save Drought-Stricken Wild Horses and Burros on Public Lands,” News Release, August 2, 2021.

Overuse of rangelands by wild horses and burros also reduces the availability and quality of forage and water for other species and threatens riparian areas. Horses are hard on pastures. They trample vegetative cover, graze more and more intensively than cattle or wild ruminants, and often graze plants to the ground or even uproot them. Their grazing habits can change the balance of forage species, promoting growth of less favorable species and eventually accelerating soil erosion.18National Research Council, Using Science to Improve the BLM Wild Horse and Burro Program, 75; Molly M. Kaweck, John P. Severson, and Karen L. Launchbaugh, “Impacts of Wild Horses, Cattle, and Wildlife on Riparian Areas in Idaho,” Rangelands 40, no. 2 (2018).

A 2019 paper provides a helpful survey of the research on wider environmental impacts of wild horse presence.19Kirk W. Davies and Chad S. Boyd, “Ecological Effects of Free-Roaming Horses in North American Rangelands,” BioScience 69, no. 7 (2019). The authors discuss how wild horse grazing intensity can also be more severe than managed cattle because unmanaged horses tend to focus grazing in appealing riparian areas. Additionally, wild horses tend to exclude other wildlife such as elk, pronghorn, and mule deer from water sources, exacerbating their impacts. Evidence also indicates that heavy horse grazing can decrease the density of sagebrush, which can take decades to recover. Furthermore, populations of the greater sage grouse, an indicator species for wider environmental conditions, tend to decline when wild horse populations exceed their appropriate management levels, according to a 2021 U.S. Geological Survey study.20Peter S. Coates et al., “Sage-Grouse Population Dynamics are Adversely Affected by Overabundant Feral Horses,” The Journal of Wildlife Management 85, no. 6 (2021): 1132-49.

The BLM’s main management strategy to mitigate these environmental impacts is to gather and remove excess animals from public rangelands. Healthy animals that are removed are kept in off-range holding pastures or corrals in the care of the BLM and private contractors. Of the roughly 60,000 animals currently in holding facilities, approximately 40,000 are on off-range pastures in long-term care. Such facilities provide open space and generally house older, unadopted, and unsold wild horses for the rest of their lives. Corrals are used to hold animals for a short term while they are being readied for adoption. Short-term care is approximately 2.5 times more costly than long-term care due to increased need for hay, veterinary services, and other factors.21BLM, Wild Horse and Burro Program: Fiscal Year 2023; “Long-term holding typically is used for older and other animals with less potential for adoption or sale; the average cost was estimated in 2020 at about $2 per animal per day. By comparison, the cost of short-term corral facilities was about $5 per animal per day.” Vincent, Wild Horse and Burro Management, 1-2.

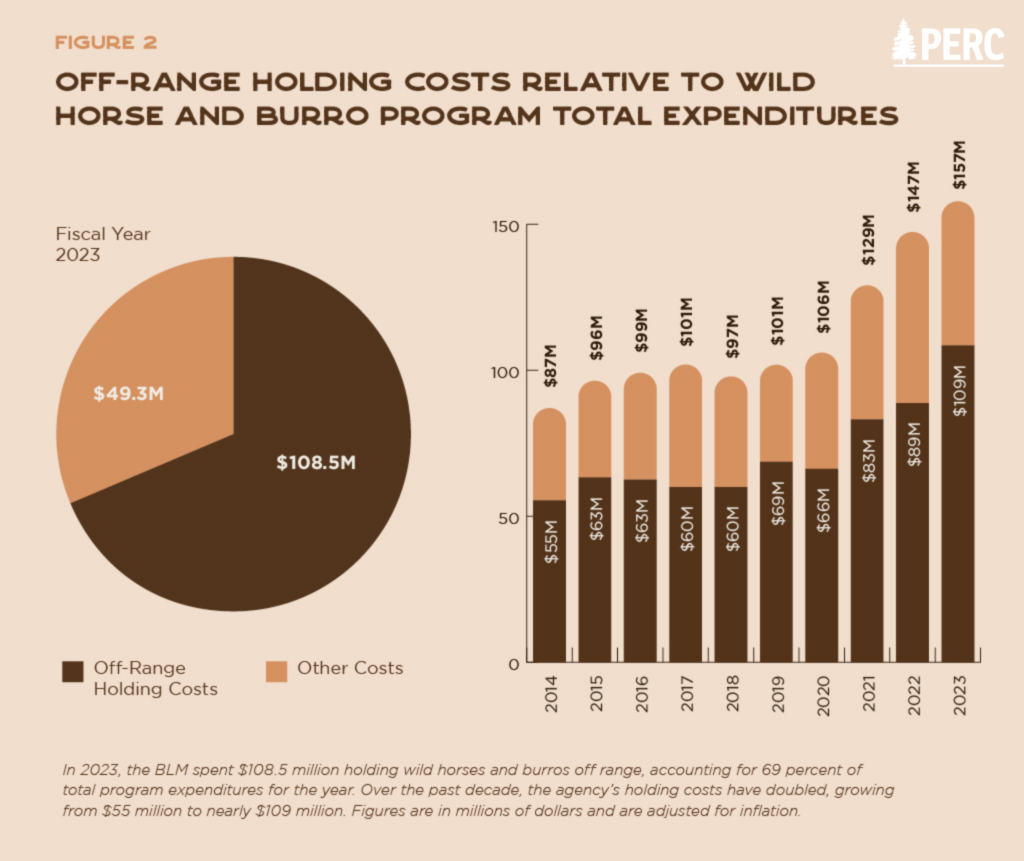

In 2023, the BLM spent $108.5 million holding wild horses and burros, totaling 69 percent of the program’s expenditures for the year. Over the past decade, the agency’s holding costs have doubled even after adjusting for inflation.22BLM, Program Data.

The BLM also uses contraceptive shots for mares to slow the population growth of wild horses on the range. The main drug used is PZP, a birth-control injection for horses that has a long history of use in wildlife species and is considered safe but is most effective for only one year and requires periodic boosters.23BLM, “Top 5 Things to Know About Wild Horse and Burro Fertility Control,” September 29, 2021; “Fertility Control,” American Wild Horse Campaign, accessed January 29, 2024. In 2022, the agency treated 1,622 mares with contraceptives, a record number but only approximately 4 percent of all wild mares.24BLM, Wild Horse and Burro Program: Highlights from Fiscal Year 2022. The agency has reported that one dose of contraception costs approximately $2,500, which includes costs for gathering, treating, and holding animals for a short term.25Vincent, Wild Horse and Burro Management, 2. In light of these challenges, the BLM is researching possibilities for permanent or longer-lasting horse birth control. A “catch, treat, hold, release” initiative piloted in 2023 with the Reveille Herd in Nevada involved capturing a group of horses, injecting them with the contraceptive, holding them for 30 days, and then administering a second dose to boost the efficacy of the treatment.26This herd is near its appropriate management level, so reducing its fertility is expected to be more effective at stabilizing the population than for more overpopulated herds. BLM, “New Wild Horse Fertility Control Effort Underway,” BLM Blog, August 11, 2023. Still, given the difficulties of reducing fertility with current methods, the agency continues to use other tools at its disposal to manage on-range populations.

Rangelands

Large herds of wild horses and burros are found throughout the western United States. The rugged animals have evolved to live in challenging environments, but not in the numbers seen today. The herds throw ecosystems out of balance, degrading native vegetation like sagebrush and overwhelming limited water supplies that can harm wildlife including elk, pronghorn, and bighorn sheep. Because the populations exceed what the landscape can support, it’s common for horses and burrows to die of starvation and thirst.

Wild Horse and Burro Adoptions

For decades, the BLM has allowed people to adopt wild horses and burros that have been gathered and removed from public rangelands. Adoption is the primary way horses leave off-range holding facilities, placing them in private care and removing them from taxpayer expense.27Fitzgerald and Rucker, You Can’t Drag Them Away. Members of the public can adopt the animals at auction, and adopters must agree not to sell the horses for slaughter. Adopters are eligible to receive title after providing a year of good care to the animals and must consent to welfare checks during that year. Once an adopted animal is titled to its new owners, it becomes private property and is no longer subject to the Wild and Free-Roaming Horses Act.28BLM, “Adoption Program,” Wild Horse and Burro Program, accessed February 12, 2023. In 2023, a total of 6,220 wild horses and burros were adopted.29BLM, Program Data. BLM adoptions of mules are generally reported as burros.

Each horse and burro adopted saves the agency an estimated $22,500 to $29,000 in holding costs over its lifetime.30BLM, More Than 8,000 Wild Horses and Burros Found New Homes; BLM, Wild Horse and Burro Program: Fiscal Year 2022. Since 2017, however, removals of horses from public rangelands have largely outpaced placements into private care through adoption and other means. In fiscal year 2022, for instance, the agency removed 20,193 wild horses and burros from the range, while only 7,793 animals were adopted, sold, or transferred.31BLM, Program Data. The following year, the agency drastically reduced removals due to capacity constraints in off-range holding facilities and soaring costs of caring for animals in them.32Scott Streater, “BLM Tests Fresh Strategy for Wild Horse Birth Control,” E&E News, August 18, 2023.

In an effort to improve adoption prospects, the BLM has partnered with groups such as Mustang Champions, prison programs, and horse trainers to train wild horses and burros prior to adoption. Given that taming wild horses can be daunting to the average potential adopter, animals that have been trained are appealing, and trained horses have historically been much more likely to be adopted than untrained ones. Since 2007, Mustang Heritage Foundation has helped the agency train and place into private care more than 20,000 animals.33BLM, “BLM Awards More than $4.7 Million for Wild Horse and Burro Training and Adoption Programs,” News Release, March 27, 2023; BLM, “Florence Wild Horse and Burro Training and Off-Range Corral,” Wild Horse and Burro Off-Range Corrals, accessed January 10, 2024. The BLM does not regularly report training costs but has estimated an average cost of about $1,500 to complete any placement, which includes “activities to make the animals more marketable, such as training, advertising, and transporting,” according to the Congressional Research Service.34This estimate does not include the $1,000 incentive payment for untrained animals. Vincent, Wild Horse and Burro Management, 2. In fiscal year 2022, over 2,000 wild horses and burros were trained through such programs.35BLM, Wild Horse and Burro Program: Highlights from Fiscal Year 2022.

The BLM has long required a minimum fee of $125 to adopt a wild horse or burro. Prior to the adoption incentive program, a comprehensive 2016 analysis of the wild horse program by PERC fellows Randy Rucker, Timothy Fitzgerald, and Vanessa Elizondo concluded that a fundamental problem was that there were too few prospective adopters of wild horses at the $125 fee, leading to the accumulation of animals in holding facilities and a spiraling burden to taxpayers.36Vanessa Elizondo, Timothy Fitzgerald, and Randal R. Rucker, “You Can’t Drag Them Away: An Economic Analysis of the Wild Horse and Burro Program,” Journal of Agricultural and Resource Economics 41, no. 1 (2016). The researchers suggested three possible solutions: 1) increase demand for the horses, perhaps by expanding training programs, 2) decrease the supply of horses that the BLM wishes to place, perhaps by expanding use of PZP to reduce fertility rates, or 3) decrease the minimum adoption fee. The authors suggested the third option, specifically advocating that the agency pay rather than charge wild horse adopters. After encouragement and outreach from PERC on this policy reform, the BLM implemented a version of this strategy as the agency’s adoption incentive program.

If populations continue to grow, the animals will pose greater risks to rangeland ecosystems and wildlife, eventually warranting more removals that would impose higher future holding costs and long-run taxpayer burdens.

In 2019, the BLM implemented a $1,000 incentive payment for individuals who adopt an untrained wild horse or burro. (Animals trained by the BLM or partner programs are not eligible for the incentive.) The payment aims to assist with expenses for training and care and to encourage the adoption of these animals. Adopters must still pay a $125 fee, agree not to sell the animals for slaughter, have no history of violating the terms of the wild horse program, and consent to compliance inspections by BLM officials. After a year, the adopter is given title to their horse once a veterinarian or BLM-authorized officer has attested that the animal has received proper care. Up to 60 days after title is received, the incentive payment is made to the adopter.37BLM, “Adoption Incentive Program,” Wild Horse and Burro Program, accessed December 1, 2023. In 2022, several measures regarding the adoption process were made more stringent, including moving up the compliance inspection from one year to six months, reestablishing a $125 fee rather than a $25 one, and paying the full incentive after the title date rather than half upfront and half after title. BLM, “BLM Enhances Protections in Wild Horse and Burro Adoption Incentive Program,” News Release, January 26, 2022.

Sales and Transfers

In addition to adoption, there are two other ways that wild horses and burros can leave BLM care. Horses that have been offered at adoption auctions at least three times or are over 10 years old can be sold, with fewer restrictions on transfer and a lower fee ($25 rather than $125).38BLM, “Sales Program,” Wild Horse and Burro Program, accessed December 1, 2023. However, the sales program is relatively small, with historically many fewer horses leaving BLM possession through sales than adoptions. Additionally, since 2017 the BLM has been authorized to transfer excess wild horses and burros to other government agencies for use as “work animals.”39BLM, Program Data. In 2023, 1,798 animals were sold, and 27 were transferred to other agencies.40BLM, More Than 8,000 Wild Horses and Burros Found New Homes.

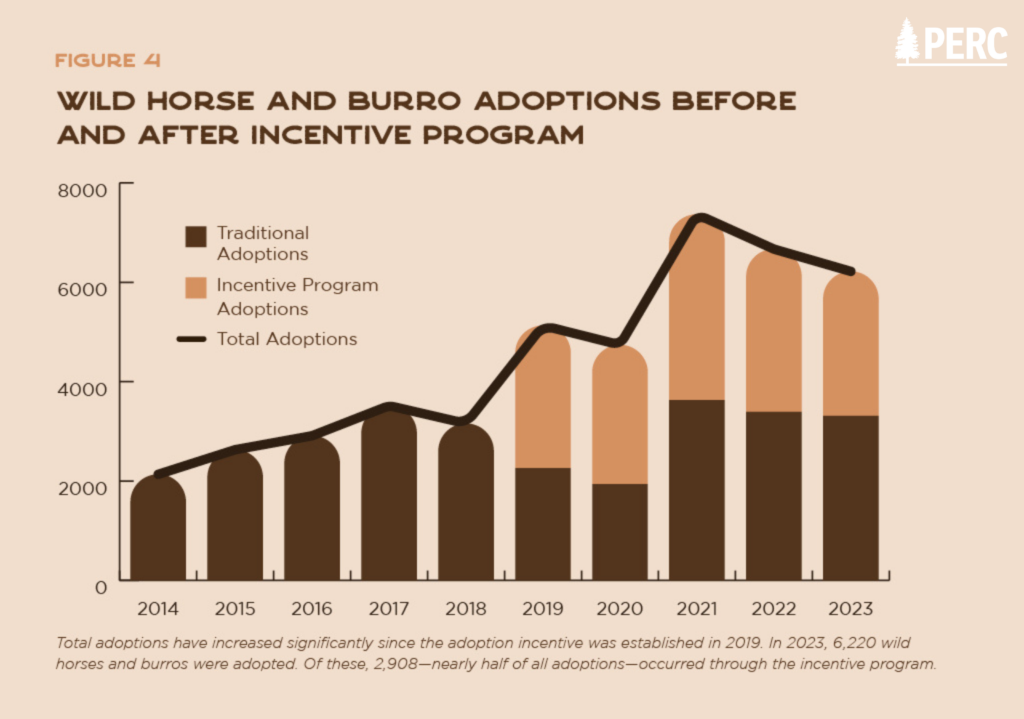

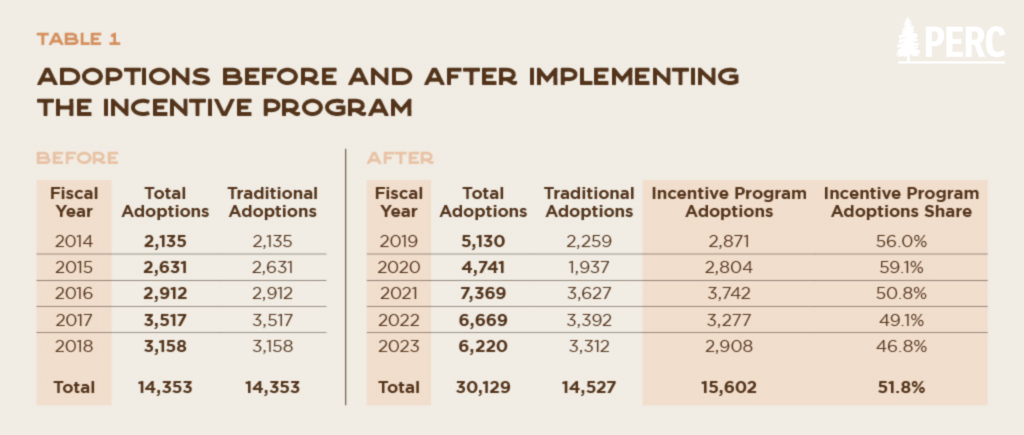

Adoption Incentive Program Assessment

Average total adoptions of wild horses and burros have more than doubled since the implementation of the incentive, increasing from an average of 2,871 animals each year in the five years prior to the incentive to 6,026 animals during the program’s first five years. The trend in total adoptions has clearly increased, as displayed in Figure 4. Since being implemented in 2019, more than 15,000 wild horses and burros have been adopted through the incentive program, accounting for nearly 52 percent of all adoptions. (See Table 1.) In 2023, more than 6,000 animals were adopted. Of these, nearly half occurred through the adoption incentive program.

It’s possible that some people who have adopted horses through the incentive program would have adopted horses even if the incentive were never implemented. In the first year of the incentive program, for instance, traditional (non-incentive program) adoptions decreased even as total adoptions increased, perhaps suggesting some would-be traditional adopters became incentive-program adopters. The absolute number of incentive adoptions, therefore, may overstate the program’s overall effect at boosting adoptions. For that reason, calculations of cost savings through the incentive program presented below likely represent maximum estimates. Still, it’s clear that total adoptions have significantly increased in the years since the incentive program was established and have remained higher than pre-incentive levels, generating progress toward the agency’s main goal of placing more horses into private care.41While some adopters may have switched from traditional to incentive adoptions, other factors suggest the amount of switching may be limited. For one thing, some people forgo receiving the incentive for (untrained) adopted horses that are eligible for the incentive payment, as indicated by the agency training far fewer horses each year than are adopted. (See BLM, Program Data.) Moreover, the incentive program requires more work and information from adopters, which could deter some adopters. Such factors include completing additional paperwork, complying with a six-month inspection, getting veterinarian or similar sign-off at the one-year mark, and sharing bank account information with the agency to receive payment. BLM National Wild Horse and Burro Program Office, Personal Correspondence, February 2024.

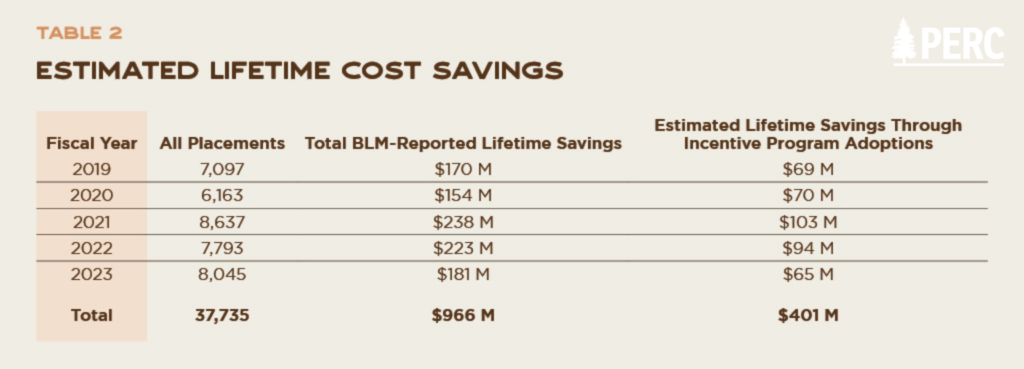

The BLM generally releases an estimate of lifetime cost savings for all animals placed into private care in a given year. In 2023, for instance, placements—including all adoptions, sales, and transfers—totaled 8,045, and the agency reported a total lifetime cost savings of $181 million for those placements.42BLM, More Than 8,000 Wild Horses and Burros Found New Homes. In 2023, the agency estimated that each placement would save approximately $22,500 in costs over the lifetime of each animal. Applying the agency’s cost savings estimates to the incentive program suggests that the more than 15,000 incentive adoptions since 2019 will save taxpayers roughly $400 million over the lifetimes of those animals. (See Table 2.) The incentive program, therefore, is on track to place more than 30,000 animals in private homes over its first decade and save more than $800 million in lifetime costs.

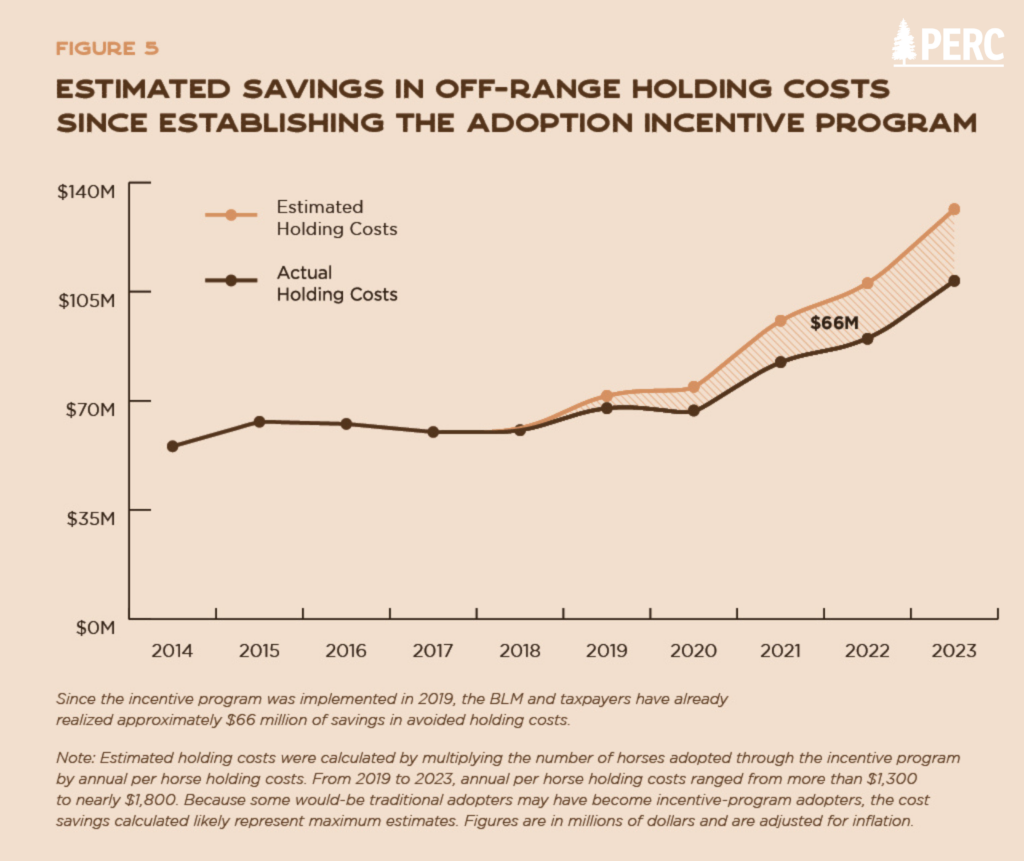

Moreover, the increase in adoptions after the incentive program was established has likely already saved an estimated tens of millions of dollars in avoided costs. In 2023, for instance, off-range holding costs totaled $108.5 million. Without the adoption incentive—and with more wild horses in holding facilities—those costs likely would have exceeded $130 million. (See Figure 5.) In the five years since the incentive program was implemented, the BLM and taxpayers have already realized approximately $66 million of savings in avoided holding costs for the 15,000 animals adopted through the program. Because the incentive payments for those adoptions cost the agency less than $16 million, the program’s net savings has already been approximately $50 million.43While this net savings estimate compares holding-cost savings to the direct costs of incentive payments, it does not account for the indirect costs of administering the adoption incentive program. And the savings from those already adopted animals will continue to compound each year, even as new adoptions will help limit future holding costs further.

The total annual adoption count was generally increasing before the incentive program, but the number of adoptions has risen notably since the implementation of the program. While the incentive is just one tool that the BLM has to address the wild horse and burro crisis, it seems to have furthered the agency’s main goal of placing more wild horses and burros into private care.

Conflict

The BLM faces a balancing act when it comes to wild horses. Horse advocacy groups who criticize the gathering and removal of wild horses and burros from public rangelands have repeatedly sued the agency over these practices.44Vincent, Wild Horse and Burro Management, 1. Groups such as American Wild Horse Conservation, for instance, are critical of the BLM’s practice of removing wild equines from public rangelands and have encouraged the expansion of fertility-control measures to decrease the need for removals.45“Myths & Facts About the BLM Wild Horse and Burro Program,” American Wild Horse Conservation, accessed March 11, 2024. Yet if populations continue to grow, the animals will pose greater risks to rangeland ecosystems and wildlife, eventually warranting more removals that would impose higher future holding costs and long-run taxpayer burdens.

Moreover, there is some controversy and lack of transparency around the BLM’s methods for collecting population data and setting appropriate management levels, discussed at length in a 2013 National Research Council report. The report concludes that the BLM’s estimate of a 20 percent annual population growth rate (leading to a population doubling roughly every four years) is likely accurate, but it offers suggestions for improving the precision of population tracking that would facilitate more accurate population counts.46National Research Council, Using Science to Improve the BLM Wild Horse and Burro Program, 31-32, 53-56.

Another criticism of the BLM is that it has not enforced its adoption agreements to prevent adopted horses from facing abuse or slaughter. According to a 2021 New York Times report, BLM horses that had been adopted and titled through the incentive program were allegedly found at auctions attended by slaughterhouse brokers.47Dave Philipps, “Wild Horses Adopted Under a Federal Program Are Going to Slaughter,” The New York Times, May 15, 2021. The agency has since revised several policies aimed at increasing oversight and reducing the potential for abuse of the program, and in 2023, the BLM stated that it is “unaware of any evidence that untitled wild horses or burros are being sent to slaughter.”48Mark Scaglione and Erin McLaughlin, “Wild Horses Put Up for Adoption by the Government Are Ending Up at Risk for Slaughter,” NBC News, September 27, 2023. Specifically, the agency now delays payment of the full incentive until up to 60 days after title date, rather than paying half of the incentive at the time of adoption and half at title date. It has also reestablished an adoption fee of $125 rather than the $25 one implemented at the program’s outset. Additionally, incentive program adoptions now require sign-off by a veterinarian or BLM-authorized officer before an adopter can receive the payment.49BLM, BLM Enhances Protections.

Recommendations

The incentive program has helped increase adoptions, but the BLM still struggles to place enough wild horses and burros into private care to alleviate the financial burden of holding facilities and ultimately relieve pressure on public rangelands. The agency aims to place 10,000 animals into private care through adoptions and sales in 2024.50BLM, BLM 2024 Wild Horse and Burro Estimates. Several changes to the incentive program specifically or the wild horse and burro program generally can help the BLM achieve its goal and manage the wild horse crisis in the future.

1. Increase the adoption incentive payment by experimenting with alternative frameworks.

The $1,000 incentive is quite small compared to the taxpayer savings when a horse leaves BLM holding facilities and enters into private ownership. Because potential adopters seem responsive to the incentive, finding responsible ways to raise the payment amount would likely further encourage adoptions and help set the wild horse and burro program on a sustainable path. The BLM would be prudent to pilot different approaches that allow the agency to learn from what works and then adapt the program’s structure. The agency should also ensure that any future framework for the incentive program retains existing protections for wild horses and burros throughout the adoption process.

One option to raise the total payment would be to increase the number of incentive payments per adoption, subject to waiting periods and additional compliance inspections. For instance, an adopter could be eligible for additional incentive payments in future years if they retain the animal and continue to satisfy compliance criteria. If the agency decided to raise the total incentive payment to $3,000, for example, then it might make three $1,000 payments over the course of three years. Another option would be for the BLM to establish a “frequent adopter” program, whereby people who regularly adopt wild horses or burros and demonstrate that they care for them responsibly could earn bonuses for the animals they have retained.

Given the large cost savings of placing horses into private care, the BLM seems to have substantial margin to tinker with the incentive payment amount, timing, and structure to see whether tweaks can help increase total placements. Any program structure should provide flexibility to adjust parameters over time as the agency learns from small-scale changes and as the supply or demand of wild horses changes. Lastly, it would have to account for the increased administrative costs that would come with additional payments, inspections, and complexity to the program.

2. Harness private partnerships to place even more wild horses and burros with adopters in the East.

While the BLM holds auctions across the country and makes horses available to adopt online, it could benefit from connecting more potential adopters in the East to wild horses and burros in the West.51BLM, “Adoption and Sale Events,” Wild Horse and Burro Program, accessed February 1, 2024. Half of the top 10 states by horse population are in the East, and eastern states already account for more than one-third of the agency’s total placements.52USDA, “2017 Census of Agriculture, Table 18. Equine – Inventory and Sales: 2017 and 2012,” National Agricultural Statistics Service (2019); Derrick Henry, “Wild Horse and Burro Adoptions Remain Important Programs for the BLM,” April 6, 2023. Whether it’s a wild horse that holds mystique as a fabled western mustang, or a humble burro in need of a good pasture to live out its years, adopting a wild equine appeals to many easterners. Linking more horse owners and enthusiasts in the East with the supply of wild animals in the West is a promising way to boost adoptions. The agency estimates that demand exists to more than quadruple the number of eastern adoptions over the next five years, to a total of 13,000 animals.53BLM, “Additional Funding Needs to Increase Animal Placement in the Eastern States Region,” BLM Eastern States Wild Horse and Burro Program, July 5, 2023. But transport and logistics present significant challenges.

The BLM’s only off-range corral located east of the Mississippi River is in Illinois.54BLM, “Off-Range Corrals,” Wild Horse and Burro Program, accessed February 1, 2024. While the agency holds approximately 20 adoption events in eastern states each year, it lacks short-term holding facilities in the East where horses and burros can rest, recover for a few days, and be readied for adoption. In some cases, logistical challenges dictate that animals arrive directly at an auction event after a long journey. Moreover, the significant expenses to truck horses cross-country limit the agency’s efforts to make more animals available to eastern adopters.55BLM Eastern States State Office, Personal Correspondence, March 2024.

The agency should aim to harness enthusiasm and funding from private partners to mitigate transport and logistics costs and grow adoptions of wild horses and burros in the East. A creatively marketed “Pony Express” initiative, for instance, could not only attract funding to bring more wild horses eastward for adoption but also increase awareness among eastern horse owners. Tapping into private funding could provide flexible resources that allow the agency to rent short-term holding facilities in the locations and at the times that it most needs them. The BLM’s philanthropic partner, the Foundation for America’s Public Lands, makes a natural ally in such an effort, and conservation groups interested in public rangeland health or other interested donors who care about the wild horse crisis generally could also become potential partners.

3. Leverage the adoption incentive’s cost savings to support other strategies that can help alleviate the wild horse and burro crisis.

The total wild horse population both on and off public rangelands is on an unsustainable trajectory, increasing by 50 percent over the last decade. In several recent years, the BLM increased the number of horses removed from western lands, which helped reduce the animals’ ecological impact. But now the agency is committed to a massive future burden of paying to care for all of those animals off range.

The agency has used the adoption incentive program to help double adoptions over the past five years. But the program will not alone alleviate the fundamental issue of an on-range population triple its target level. Currently, 69 percent of the wild horse and burro program budget is spent on off-range holding facilities, limiting the BLM’s ability to devote resources to other initiatives, such as fertilization control. If increases in adoptions can help decrease agency holding costs, it will have more of its budget available to devote to other aims, which may also include monitoring and enforcing provisions of the incentive program.

Ultimately, the rate of wild horse placements must exceed population growth of the animals for the agency to reduce its holding capacity and costs over the long term. As the BLM looks to the future, complementary options to help mitigate the wild horse crisis could include investing in immunocontraception efforts, expanding training programs, or innovating new ways to place more animals into good homes.

Conclusion

The adoption incentive program can help drive a positive feedback loop between placing horses into private care and relieving stress on public rangeland ecosystems. If the incentive program can continue to boost adoptions, then it will free up capacity in holding facilities, allowing the BLM to remove animals from overpopulated rangelands and ultimately relieve pressure on ecosystems and taxpayers.

For the agency to eventually overcome the wild horse and burro crisis, it must place animals into private care faster than they repopulate on public lands. The adoption incentive program is one promising tool that can help mitigate the current crisis and promote long-term fiscal sustainability of the wild horse and burro program. The BLM will need to deftly use all of the options at its disposal to restore overpopulated ecosystems and alleviate the taxpayer burden of rising wild horse and burro populations while preserving safeguards for the animals it is mandated to protect.

About the Photographer

Ryane Nicole has been a photographer for more than 25 years. She is passionate about the craft of photography and wild horse adoption. For more information, visit RyaneNicole.com.

“I use imagery to show how impactful these horses are to our lives. I can say with experience how deep the impact we can make on theirs. I have had my life changed by a mustang that I named Aslan. I have personally seen the beauty in giving Aslan a second chance through adoption. Not only is she a sweet horse, but she is a jumper and participated in her first rodeo last summer with my daughter barrel racing. She loves riding in the mountains. When I go to visit her, she comes to my voice when I call her name. We have a unique bond that not only fills my heart, but connects with my soul.

I have made a conscious decision to be one voice of many to show how these horses are uniquely designed to co-exist with man and what man can learn from the horse. I believe continuing the adoption programs and continuing to use our voices is where refuge and beautiful reverence is shown to this majestic creature.”