Introduction

In January 2025, a coalition led by the Confederated Tribes of Siletz Indians received more than $1.5 million in federal and private funding to support sea otter reintroduction planning efforts along the coasts of Oregon and Northern California. The grant—one of the largest ever dedicated to sea otter recovery—was awarded by the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation and will fund habitat assessments, stakeholder outreach, and tribal coordination.1Elakha Alliance, “Siletz Tribe Receives Major Grant to Aid Tribes in Returning Sea Otters to Oregon and Northern California,” Elakha Alliance, January 26, 2025; Courtney Flatt, “Siletz Tribe Gets $1.56 Million to Reintroduce Sea Otters to Coastal Waters,” Oregon Public Broadcasting, January 27, 2025. The announcement marked a significant milestone in a long-running campaign to return sea otters to parts of their historic range where they have been absent for more than a century.

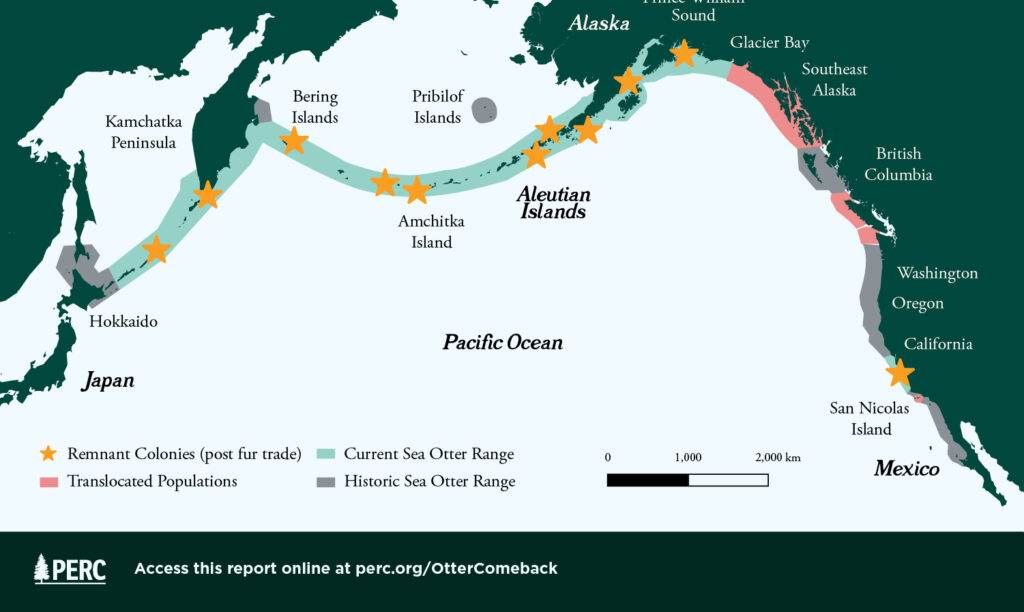

Over the summer of 2024, two sea otters were briefly spotted off the coast of Oregon, a rare and exciting event in waters where the species was once abundant.2April Ehrlich, “Sea Otters Spotted off Oregon Coast, a Rare Sight After a Century of Near-Extinction,” OPB, July 3, 2024. Historically, the species spanned nearshore waters in an arc stretching from Japan to Mexico. Indigenous peoples have long held sea otters in high regard, historically trading their furs or using the pelts to make treasured robes.3Elakha Alliance, “Sea Otters and Oregon Coast Tribes,” accessed September 4, 2024, https://www.elakhaalliance.org/learn/the-history-of-sea-otters-in-oregon/sea-otters-and-oregons-coastal-native-tribes/. Yet by the early 20th century, commercial fur trapping had reduced their numbers to a few scattered colonies, with perhaps only 2,000 animals surviving.4A. Doroff, A. Burdin, and S. Larson, “Enhydra lutris,” The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species (2021, revised 2022): e.T7750A219377647. Since then, sea otters have rebounded in some areas thanks to legal protections and targeted translocations in parts of Alaska, Washington, and California. Still, the species faces ongoing threats, including oil spills, fishing gear entanglement, and predation by sharks and orcas.5Doroff, Burdin, and Larson, Enhydra lutris.

Today, a notable gap in the species’ range stretches from San Francisco Bay to Oregon, weakening the resiliency of coastal ecosystems. Sea otters play an important ecological role by preying on herbivores such as sea urchins. Without sufficient predators to control their density, urchins can overgraze kelp and seagrass habitat.6U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, “Feasibility Assessment of Sea Otter Reintroduction to the Pacific Coast” (2022): 13. Researchers partly attribute the loss of more than 90 percent of kelp forests in Northern California waters roughly a decade ago to the absence of sea otters.7When anomalously warm waters killed purple sea urchins’ main predator, a type of sea star, urchins were left to devastate kelp unchecked. USFWS, Feasibility Assessment of Sea Otter Reintroduction, 56.

Groups such as the Elakha Alliance, Defenders of Wildlife, and several tribal nations have long advocated for sea otter restoration not only as a matter of ecological recovery but also as a step toward healing cultural and environmental legacies of losing the species in certain areas.8Elakha Alliance, “Bringing Back Oregon’s Sea Otters,” accessed September 4, 2024, https://www.elakhaalliance.org/; Jacqueline Covey, “Restoring Sea Otters Throughout the Pacific Coast,” Defenders of Wildlife, October 3, 2023. The recent grant reflects growing momentum among conservationists to advance reintroduction planning. The federal government, which would have to sanction a reintroduction of federally regulated sea otters, continues to weigh the potential implications.

In 2022, acting on orders from Congress, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service began to explore the feasibility of reintroducing sea otters to the Pacific Coast, identifying Oregon and Northern California as the most beneficial potential reintroduction areas.9USFWS, Feasibility Assessment of Sea Otter Reintroduction, vi-vii. While the service has not indicated whether it will propose a reintroduction, it has been gathering feedback from local communities and been assessing key ecological, regulatory, and socioeconomic factors.10U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, “Exploring Potential Sea Otter Reintroduction,” accessed September 4, 2024, https://www.fws.gov/project/exploring-potential-sea-otter-reintroduction. Among the most sensitive issues is the potential conflict between reintroduced otters and coastal fisheries.

Sea otters consume crabs, clams, urchins, abalone, and other shellfish, many of which support commercial and tribal livelihoods. For operators of small fishing boats with thin margins or tribal members harvesting for subsistence and ceremony, the arrival of sea otters could mean fewer shellfish to consume or sell. Although the service concluded that reintroduction would likely yield net benefits overall, it also acknowledged that the costs would be highly concentrated and potentially contentious.11USFWS, Feasibility Assessment of Sea Otter Reintroduction, 131, viii.

To avoid repeating past mistakes, any sea otter reintroduction must be cooperatively and creatively designed to reduce liability for affected groups, and ideally, to increase and equitably distribute the benefits.

There is ecological justification for reintroducing sea otters, and sites with suitable habitat, but history has shown that such efforts can be derailed by poorly designed policies that create clear winners and losers with no mitigation or compensation for the latter. Past reintroduction plans opposed by affected communities have generated deep and broad opposition and ill will that ultimately harmed the conservation prospects of reintroduced species. For instance, controversial proposals to reintroduce grizzly bears in the Bitterroot and North Cascades Ecosystems have stalled largely due to political backlash stemming from perceived inequities in the distribution of costs and benefits.12Hunter Sapienza and Ya-Wei Li, “Reintroduction: An Assessment of Endangered Species Act Experimental Populations,” Environmental Policy Innovation Center (2021); John Stang, “Why the US Plan to Reintroduce Grizzlies to the North Cascades Has Stalled,” Cascade PBS, May 2, 2025. To avoid repeating past mistakes, any sea otter reintroduction must be cooperatively and creatively designed to reduce liability for affected groups, and ideally, to increase and equitably distribute the benefits.

This brief provides a synthesis of past efforts at sea otter reintroductions with the goal of grounding any future reintroduction efforts and policies in “lessons learned.” It summarizes relevant background on sea otter populations and past translocation efforts, particularly the complex history of reintroduction to San Nicolas Island. It then examines the key ecological, legal, regulatory, social, and economic dimensions of a potential reintroduction to the Pacific Northwest. Finally, it explores how cooperative frameworks and compensatory mechanisms might help conservationists turn a vulnerable species from a perceived threat into a shared asset for coastal communities.

Current Sea Otter Populations

Sea otters rely on shallow nearshore marine habitats that provide abundant food resources and shelter from predators, including rocky coastlines, kelp forests, and inlets and estuaries protected from severe winds and swells. They primarily forage within one kilometer of shore and at depths of less than 30 meters, where they forage on marine invertebrates like urchins, clams, and abalone. Shallow coastal waters not only support such prey species but also offer features for resting and grooming. Sea otters are particularly associated with kelp beds, which they use to rest and rear pups. The availability of such habitats is essential for sustaining sea otter populations.13Doroff, Burdin, and Larson, Enhydra lutris.

Sea otters in the United States consist of two subspecies: northern and southern.14The subspecies are Enhydra lutris kenyoni and Enhydra lutris nereis, respectively. Northern sea otters inhabit coastal waters from Alaska to Washington, with occasional sightings in Oregon.15Terry Richard, “Rare Sea Otter Confirmed at Depoe Bay,” The Oregonian, February 20, 2009; Amy-Xiaoshi DePaola, “Rare Sea Otters Spotted in Cannon Beach,” KGW8, June 29, 2024; Ehrlich, Sea Otters Spotted off Oregon Coast. Of the nearly 100,000 northern sea otters in U.S. waters, more than 95,000 are in Alaska, with an additional 2,000 to 3,000 in Washington.16Marine Mammal Commission, “Northern Sea Otter,” accessed September 4, 2024, https://www.mmc.gov/priority-topics/species-of-concern/northern-sea-otters/. The Southwest Alaska population has precipitously declined, likely due to predation by orcas, and is listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act.17Determination of Threatened Status and Special Rule for the Southwest Alaska Distinct Population Segment of the Northern Sea Otter (Enhydra lutris kenyoni), Final Rule, 70 Fed. Reg. 46366 (August 9, 2005); M. Tim Tinker et al., “Sea Otter Population Collapse in Southwest Alaska: Assessing Ecological Covariates, Consequences, and Causal Factors,” Ecological Monographs 91, no. 4 (2021): e01472.

Southern sea otters, or California sea otters, are found along the Central and Southern California coast. The entire current population of about 3,000 individuals descends from a remnant colony of 50 discovered near Big Sur in 1938. The subspecies, estimated to once have numbered 16,000, was listed as threatened in 1977 due to its small size, limited range, and vulnerability to oil spills.18Determination That the Southern Sea Otter Is A Threatened Species, 42 Fed. Reg. 2965 (January 14, 1977), 2966. Today, there are approximately 3,000 southern sea otters, just shy of the recovery goal of 3,090 otters. However, the Fish and Wildlife Service has concerns about limitations to future range expansion due to shark predation and has indicated that it may soon change the species’ recovery goal.19A petition to delist the species filed in 2021 was rejected. One Species Not Warranted for Delisting and Six Species Not Warranted for Listing as Endangered or Threatened Species, 88 Fed. Reg. 64870 (September 20, 2023), 64879-80; U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, “Species Status Assessment Report for the Southern Sea Otter (Enhydra lutris nereis),” U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Region 8 (2023).

Past Reintroductions

Efforts to reintroduce sea otters to their historical range have had mixed results, offering useful lessons for future conservation initiatives.

Northern Sea Otter Reintroductions: Alaska, Washington, and Oregon

The 1960s translocation of about 400 northern sea otters to Southeast Alaska yielded a population that grew rapidly, resulting in numbers that exceed 22,000 today. The region has vast high-quality otter habitat with abundant, accessible prey and shelter from predation risk, including many inlets, bays, estuaries, and islands with shallow waters. In general, translocated populations have grown much more slowly, especially in areas where linear shallow waters bound by the continental shelf restrict otter expansions only to the north or south.20U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, “Sea Otter Open Houses 2023: Exploring Potential Sea Otter Reintroduction Oregon and Northern California: Appendix A: Answers to Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs),” August 2024, 7. A 1969–70 translocation of 59 northern sea otters to Washington has become an established population nearing 2,800, although its range remains limited to the northern half of the state’s coast.21USFWS, Appendix A: Answers to Frequently Asked Questions, 3. By contrast, a 1970–71 reintroduction to the Oregon coast failed, despite 93 individuals being released. Despite sufficient habitat and prey, many of the released sea otters quickly dispersed from the release sites, and they failed to remain in sufficient numbers to establish a sustainable population. The Fish and Wildlife Service notes that “there is no clearcut explanation for why the Oregon reintroduction failed while others succeeded, and it may have just been a matter of chance.”22USFWS, Appendix A: Answers to Frequently Asked Questions, 1-2.

Southern Sea Otter Reintroduction: San Nicolas Island, California

The only major reintroduction effort for the southern sea otter occurred from 1987 to 1990, when 140 otters were translocated to San Nicolas Island, a remote Channel Island off Southern California.23Termination of the Southern Sea Otter Translocation Program, 77 Fed. Reg. 75266 (December 19, 2012), 75269. The effort aimed to establish a second population to guard against the risk of an oil spill wiping out the main population near Big Sur. Today the San Nicolas population is estimated at 146 otters.24Marine Mammal Commission, “Southern Sea Otter,” accessed July 22, 2024, https://www.mmc.gov/priority-topics/species-of-concern/southern-sea-otter. Its complicated history is instructive.25For more see Tate Watkins and Madison Yablonski, “Turn Reintroduced Species Into Assets,” in “A Field Guide for Wildlife Recovery,” Property and Environment Research Center (2023): 30-33, and Jonathan Wood, “Will Sea Otters Soon Return to San Francisco Bay?” Property and Environment Research Center, December 18, 2019.

Congress authorized the reintroduction under section 10(j) of the Endangered Species Act (ESA), which allows for reduced regulation of experimental populations. The Marine Mammal Protection Act (MMPA) did not offer the same sort of regulatory flexibility, however, so in 1986, Congress passed legislation that would shield fishing operators from regulatory conflict under that statute.26An Act to Improve the Operation of Certain Fish and Wildlife Programs, Pub. L. No. 99-625, 100 Stat. 3500 (1986).

Through various measures in its legislation, Congress sought to preempt potential conflicts. First, the law directed the Fish and Wildlife Service to cooperate with state agencies. It also established a “translocation zone,” where otters would be released, with a “management zone” surrounding it, from which otters would be relocated back to the translocation zone. The aim of the zonal management plan was to “prevent, to the maximum extent feasible, conflict with other fishery resources”—namely, commercial fishing. Any incidental take of southern sea otters within the management zone was not treated as a violation of the ESA or the MMPA. In short, Congress aimed to ensure that state authorities and the fishing industry would be partners in the endeavor and protect them from regulatory liability.

Despite those safeguards, the program struggled from the outset. High dispersal during and after translocation led the Fish and Wildlife Service to halt introductions by 1991, when an estimated 14 adult otters remained at the island. Capturing and relocating otters from the designated management zone also proved ineffective and was abandoned by the mid-1990s. The state withdrew its support in 1997, and in 2012, the Fish and Wildlife Service formally terminated the program, deeming it a “failure.”27Termination of the Southern Sea Otter Translocation Program, 77 Fed. Reg. at 75267.

Although the reintroduction effort ended, the Fish and Wildlife Service did not remove the sea otters that remained in the island’s waters. Over the past decade, the San Nicolas population has grown by roughly 10 percent annually to reach its current level of 146 individuals, and it seems likely to continue expanding in numbers and range. Despite the official “failure” judgment by the service, the San Nicolas reintroduction has largely proven to be a conservation success, even if its history has damaged trust over potential future reintroductions.

Litigation followed the program’s termination, with commercial fishing groups challenging the elimination of the provisions shielding them from ESA and MMPA regulations when the program was terminated. Two district courts and the Ninth Circuit ultimately upheld the termination.28See Cal. Sea Urchin Comm’n v. Bean, 883 F.3d 1173 (9th Cir. 2018). Southern sea otters are now fully protected throughout their range, with no special regulatory exemptions for fisheries.29Termination of the Southern Sea Otter Translocation Program, 77 Fed. Reg. at 75268-73. The story illustrates enduring tensions over sea otter reintroduction and fishery impacts.

A New Sea Otter Reintroduction?

In 2020, Congress directed the Fish and Wildlife Service to study the feasibility of reintroducing sea otters to the Pacific Coast. The agency identified the coasts of Oregon and Northern California, the largest gap in the species’ historical range, as promising reintroduction sites, with potential benefits for the threatened southern sea otter in particular.30USFWS, Feasibility Assessment of Sea Otter Reintroduction, vii. The service concluded that reintroduction is feasible and would likely yield ecological and economic gains; however, it also acknowledged potential costs, particularly competition with shellfish harvesters.31USFWS, Feasibility Assessment of Sea Otter Reintroduction, 90. It specifically claims that initial population growth would likely be slow and, therefore, impacts would be concentrated. But it also acknowledges uncertainty over how widely sea otters would eventually disperse. Moreover, even if impacts would be small initially due to a small population, the dispersal of otters from San Nicolas Island demonstrates the unpredictable nature and scope of a sea otter reintroduction. The agency has recommended a full socioeconomic impact assessment for any future reintroduction sites, but given past experience, it must also consider the potential impacts of dispersal far beyond release sites.32USFWS, Feasibility Assessment of Sea Otter Reintroduction, viii.

Another challenge is regulatory: The MMPA allows incidental take permits to be issued for commercial fishing that applies to every species except southern sea otters.33Southern sea otters were excluded from this permitting framework in an attempt to avoid disturbing the regulatory framework of the preexisting San Nicolas Island reintroduction program. The provision originated in 1988 and was made permanent in 1994. Marine Mammal Protection Act Amendments of 1994, Pub L. No. 103-238, 108 Stat. 532 (1994). U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, “Feasibility Assessment of Sea Otter Reintroduction to the Pacific Coast: Executive Summary,” 2022. In addition, some fishing and tribal interests have expressed conditional support for a small reintroduction but only if accompanied with tools and flexibility to manage sea otter numbers.34USFWS, Feasibility Assessment of Sea Otter Reintroduction, 83, 89-90.

In sum, the trade-offs today echo those of the past: A reintroduction would aid recovery by expanding sea otters’ range but could also trigger ESA and MMPA regulations and impose costs on fisheries and coastal communities. As such, any reintroduction plan should aim to make adversely affected parties whole through mitigation or compensation programs.

Major Considerations

The Fish and Wildlife Service evaluated several hypothetical reintroduction scenarios and their direct costs, varying by subspecies and release sites in Oregon or Northern California, and limited to the reintroduction site vicinity. The scenarios illustrate how outcomes would depend on a combination of ecological, regulatory, and socioeconomic dynamics.35USFWS, Feasibility Assessment of Sea Otter Reintroduction, 115-16.

Ecological Factors

Any sea otter translocation would have significant ecological implications for sea otters, other species within the ecological community, and the health and function of the ecosystem as a whole.

Sea otter benefits: Southern sea otters cannot expand north of Pigeon Point on the California coast due to shark predation, while northern otters rarely reach Oregon.36USFWS, Feasibility Assessment of Sea Otter Reintroduction, 4, 33. Establishing a southern population in this range gap could reconnect subspecies, improve genetic diversity, and enhance resilience to threats like oil spills.37USFWS, Feasibility Assessment of Sea Otter Reintroduction, 3-4.

Ecological trade-offs: Otters may prey on vulnerable species like abalone. But they also reduce the abundance of predators and competitors of abalone. In some areas, higher otter densities have been associated with greater abalone numbers. One study found that endangered black abalone density in Central California was positively correlated with density of sea otters, potentially because abalone subject to high-otter density took refuge in crevices and other inaccessible refuges that shielded them from illegal human harvest.38USFWS, Feasibility Assessment of Sea Otter Reintroduction, 59; Peter Raimondi, Laura J. Jurgens, and M. Tim Tinker, “Evaluating Potential Conservation Conflicts between Two Listed Species: Sea Otters and Black Abalone,” Ecology 96, no. 11 (2015): 3102-3108.

Ecosystem benefits: Sea otters reduce sea urchin populations, allowing kelp forests to recover. Northern California’s kelp has declined more than 90 percent due to sea star die-offs and unchecked urchins. Southern Oregon has seen similar localized impacts. By contrast, in Central California and British Columbia, established sea otter populations have provided a buffer against widespread loss of kelp from declines in sea stars, and sea otter density is the strongest predictor of kelp canopy cover across the Pacific Coast.39USFWS, Feasibility Assessment of Sea Otter Reintroduction, 56-57; Teri E. Nicholson et al., “Sea Otter Recovery Buffers Century-Scale Declines in California Kelp Forests,” PLOS Climate 3, no. 1 (2024: e0000290. Reintroducing otters would likely restore kelp, improve biodiversity, and enhance carbon sequestration.

Regulatory and Legal Factors

The main regulatory and legal factors that could affect reintroduced sea otters are the ESA and MMPA. Whether a reintroduction effort involves northern or southern sea otters matters a great deal in terms of regulatory circumstances. All southern sea otters are listed as threatened under the ESA and, under the MMPA, are ineligible for incidental take permits in the course of commercial fishing. Northern sea otters are subject to neither of these factors.40Except for the Southwest Alaska distinct population segment of the northern sea otter, which is listed as threatened under the ESA.

Reintroducing only northern sea otters, however, would likely not promote recovery for its southern counterpart.41USFWS, Feasibility Assessment of Sea Otter Reintroduction, 52-54. Consequently, it is prudent to wrestle with the greater regulatory challenges associated with a southern sea otter reintroduction.

Endangered Species Act: Southern sea otters are listed as threatened but receive endangered-level regulations under the ESA’s blanket 4(d) rule.42See 50 CFR § 17.40, text available at https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-50/chapter-I/subchapter-B/part-17/subpart-D/section-17.40. The Fish and Wildlife Service, however, has discretion to tailor take regulations for reintroduced populations. This approach has been used widely for other species. A new reintroduction of southern sea otters could use Section 10(j) or Section 10(a)(1)(A) permits, with take authorized for both source and released populations. The service would also need to evaluate potential direct and indirect interactions with other listed species such as abalone, salmon, and murrelets, although it anticipates manageable impacts.43USFWS, Feasibility Assessment of Sea Otter Reintroduction, 59, 102.

Marine Mammal Protection Act: Unlike all other marine mammals, southern sea otters are excluded from MMPA provisions that allow for permitting of incidental take in the course of commercial fishing.44Marine Mammal Protection Act Amendments of 1994, Pub L. No. 103-238, 108 Stat. 532 (1994). In this respect, the southern sea otter is stuck in a regulatory gap arising from the unique reintroduction history of the species. They are also classified as “depleted” and a “strategic stock,” which imposes stricter regulatory thresholds.45U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Final Revised Recovery Plan for the Southern Sea Otter (Enhydra lutris nereis), v; Marine Mammal Protection Act of 1972, § 3, Public Law 92-522, 86 Stat. 1027, available as amended at National Marine Fisheries Service, The Marine Mammal Protection Act of 1972 As Amended, as amended through 2018 (2019); USFWS, Feasibility Assessment of Sea Otter Reintroduction, 92-95, 97. While MMPA permits for reintroduction activities such as capture and transport are available, the exclusion of incidental take could create challenges for fisheries management post-reintroduction.46USFWS, Feasibility Assessment of Sea Otter Reintroduction, 105.

State law: The federal government holds authority over management of marine mammals, so no state authorizations would be required for a sea otter reintroduction. The Fish and Wildlife Service notes that “as a best practice” it would coordinate with relevant states on any reintroduction.

Social and Economic Factors

A sea otter reintroduction to Oregon or Northern California could have substantial implications for commercial and recreational fisheries, tribes, oyster aquaculture, and tourists and wildlife watchers. Partly due to the ecological constraints of the region under consideration, the Fish and Wildlife Service anticipates that the impacts of a sea otter reintroduction would not be widespread but instead would remain localized for the foreseeable future. Yet it admits considerable uncertainty on that point. Accordingly, a primary recommendation of the service’s feasibility study was to conduct “a comprehensive socioeconomic impact assessment focused on likely reintroduction sites,” which it has yet to do. The agency also notes that past reintroductions demonstrate that there is no guarantee sea otters will remain at reintroduction sites, and they may disperse and establish populations elsewhere.47USFWS, Feasibility Assessment of Sea Otter Reintroduction, viii, 28. There appears to be suitable habitat, although unevenly distributed, along the coast of Oregon, making the eventual establishment of new populations likely.48M. Tim Tinker et al., “Restoring Otters to the Oregon Coast: A Feasibility Study,” Elakha Alliance (2023): 90.

Commercial recreational fisheries: A major potential cost of reintroducing sea otters is the reduction or even elimination of valuable shellfish fisheries.49Tinker, Restoring Otters to the Oregon Coast, 97. Nearly half of the diet of a recently reintroduced population could consist of commercially valuable shellfish.50USFWS, Feasibility Assessment of Sea Otter Reintroduction, 63. In its feasibility assessment, the Fish and Wildlife Service reported that all interviewees who depended on shellfish for their livelihoods expressed concern over potential reintroduction.51USFWS, Feasibility Assessment of Sea Otter Reintroduction, 84. Two of the commercial fisheries most relevant to a reintroduction include sea urchin and Dungeness crab. Other fisheries that could be affected by direct competition from sea otters include various types of clams, abalone, cockles, and oysters.52USFWS, Feasibility Assessment of Sea Otter Reintroduction, 63-75.

Oregon’s urchin fishery is small but vulnerable; Northern California’s was once larger but has declined over the past decade.53USFWS, Feasibility Assessment of Sea Otter Reintroduction, 70. Sea otters’ effect on Dungeness crab varies by region.54USFWS, Feasibility Assessment of Sea Otter Reintroduction, 64, 72-72; USFWS, Appendix A: Answers to Frequently Asked Questions, 6-7. In Oregon, most crabs are caught offshore—beyond sea otter range—though some localized effects are possible.55Tinker, Restoring Otters to the Oregon Coast, 109; USFWS, Feasibility Assessment of Sea Otter Reintroduction, 64. As with red sea urchins, clam harvest would be expected to decline significantly where established sea otter populations overlap with fisheries, especially in estuaries, as has happened elsewhere.56USFWS, Feasibility Assessment of Sea Otter Reintroduction, 67. Abalone fisheries, closed in both states due to kelp loss, could be further affected if sea otters complicate recovery plans.57USFWS, Feasibility Assessment of Sea Otter Reintroduction, 64, 69-70.

While the direct effects of sea otters on shellfish via predation are generally negative, the species may have positive indirect effects to rockfish, cod, and other finfish fisheries due to rebuilding kelp and seagrass habitat.58USFWS, Feasibility Assessment of Sea Otter Reintroduction, 64-65. Benefits may be larger in Northern California than in Oregon due to the former having greater historical kelp coverage—and greater losses of such habitat in recent years. Northern California may also stand to benefit economically due to potential positive impact on groundfish fisheries, which is a top fishery in the state by landings.59USFWS, Feasibility Assessment of Sea Otter Reintroduction, 71-72. There is a growing movement to restore kelp forests along the Pacific Coast, and control of herbivores by sea otters could help increase the success of these efforts, with possible indirect benefits through expanded habitat for commercial fisheries species.60Aaron M. Eger et al., Kelp Restoration Guidebook: Lessons Learned from Kelp Projects Around the World. Arlington, VA: The Nature Conservancy, 2022.

Tribes: Several tribes located in California and Oregon have expressed support for reintroduction, noting that they hoped it could help restore kelp ecosystems or restore connectivity between the northern and southern subspecies. Additionally, two tribes—the Confederated Tribes of Coos, Lower Umpqua and Siuslaw Indians and the Confederated Tribes of Siletz Indians—wrote the interior secretary in 2024 calling for a reintroduction of sea otters within the next five years.61Confederated Tribes of Siletz Indians, “Oregon Coastal Tribal Leaders Call for Action to Return Sea Otters to Oregon,” Press Release, June 27, 2024.

Some tribal members, however, have highlighted concerns over negative effects, including to tribal, commercial, and recreational shellfish fisheries. Two tribes in Washington have been less enthusiastic or outright opposed to reintroduction. They cited concerns over a lack of coordination with tribal co-managers during past reintroductions, a lack of a mechanism to control populations of reintroduced otters, and harms to Dungeness crab, razor clam, and sea urchin fisheries for commercial, cultural, and subsistence use for their people.62USFWS, Feasibility Assessment of Sea Otter Reintroduction, 88-90.

Oyster aquaculture: There is potential for reintroduced sea otters to prey on oysters farmed in Oregon. Potential impacts in Oregon could depend on the degree of overlap between oyster aquaculture and the reintroduction sites ultimately chosen.63USFWS, Feasibility Assessment of Sea Otter Reintroduction, 66-67.

Tourism and wildlife watching: While evidence cited is largely based on stated-preference surveys, reintroduction of sea otters could bring significant economic benefits in tourism and wildlife watching. One study of Vancouver Island tourism suggests that willingness to pay for sea otter sightseeing is nearly on par with the top driver of wildlife tours: whale watching. Another study estimated that ecotourism benefits could exceed the combined benefits to finfish industries and in carbon sequestration by nearly fourfold.64USFWS, Feasibility Assessment of Sea Otter Reintroduction, 78-79. Though exact values are difficult to predict, strong public interest in sightings off Oregon suggests reintroduction could boost coastal tourism.65Associated Press, “Rare Sea Otter Sighting Getting Lots of Attention on Oregon Coast,” Fox 12, November 25, 2021; KGW, “Sea Otter Sighting on Oregon Coast Inspires Redoubled Efforts for Species’ Reintroduction,” KGW8, July 26, 2024.

Recommendations for Cooperative Sea Otter Reintroduction

A reintroduction of sea otters to the Pacific Northwest could bring clear ecological and long-term economic benefits. But it would also impose costs, especially on shellfish harvesters and other local interests dependent on sea otter prey species. To succeed, any future reintroduction must be approached as a cooperative enterprise grounded in collaboration. One advantage is that conservationists and fishing operators have a mutual interest in restoring marine habitat degraded by purple sea urchins. While human divers have tried to combat urchin booms in limited areas, there is nowhere near the scale of resources needed to tackle the problem.66Julie Watson, “Kelp Forests Vanished in a Heat Wave. Now California Wants to Bring Them Back,” Associated Press, December 9, 2023. Reintroduced sea otters could help, and cooperative or compensatory approaches could align the incentives of locals with a reintroduction plan.

The Fish and Wildlife Service and conservation partners should abide by the following recommendations as they consider a potential sea otter reintroduction to the Pacific Northwest:

1. Weigh potential costs and identify who bears them.

The Fish and Wildlife Service must complete a detailed, site-specific socioeconomic assessment. That means identifying the communities, fisheries, and operations most exposed to sea otter impacts and estimating how much they stand to lose. The ecological case for reintroduction is strong, but it must be accompanied by a credible economic case that acknowledges the potential for localized harm.

2. Pursue compensation and mitigation strategies for affected parties.

Reintroductions opposed by affected groups have historically bred resentment and resistance. To avoid repeating those mistakes, the service and partners should actively explore how to make reintroduced otters less of a liability and, ideally, even an asset. The service has already signaled interest in several such ideas.

One approach is to directly compensate affected interests. Crucially, it would require determining who pays, how, how much, and to whom. Compensation could take the form of direct payments, support for gear modifications to reduce incidental take, or other types of regulatory relief that reward coexistence. A creative option would be to issue tradable licenses for wildlife-viewing or ecotourism, allocated preferentially to affected communities. Another could be a “sea otter stamp”—a voluntary or mandated fee paid by tourism operators, with proceeds going to those who bear the costs of reintroduction.67USFWS, Feasibility Assessment of Sea Otter Reintroduction, 131. In a similar vein, California state income tax returns provide for a line item donation to sea otter recovery efforts, which raised roughly $2 million from 2008-25. California State Coastal Conservancy, “Sea Otter Recovery Fund,” accessed October 13, 2025, https://scc.ca.gov/grants/sea-otter-recovery-fund/. This concept has a parallel in early efforts to reintroduce gray wolves in the Rocky Mountain West.68Hank Fischer, “Who Pays for Wolves?” PERC Reports 19, no. 4, (2001). Wolf impacts are likely more straightforward to mitigate than those of sea otters given they involve private property and landowners rather than public waters and various user groups.

Where shellfish losses are eventually offset by gains to finfish fisheries, thanks to improved kelp and seagrass habitat, there may also be room for compensation within fishing sectors. Many fishing operators participate in both shellfish and finfish fisheries. Fishing organizations could work to balance gains and losses across their memberships, helping smooth the distributional effects of reintroduction.69USFWS, Feasibility Assessment of Sea Otter Reintroduction, 130-31.

3. Explore potential for conservationists to participate in rights-based fisheries management.

More ambitiously, conservation groups could push for the implementation of rights-based management in fisheries affected by sea otter reintroduction. Conservationists could fund the purchase of catch shares or quotas “for sea otters,” much like individual transferable quotas used in other fisheries, as a way of reducing harvest pressure while compensating fishing outfits. While such mechanisms do not currently exist for many shellfish fisheries, they could be modeled on similar rights-based approaches used elsewhere in marine conservation.70Christopher Costello, Steven D. Gaines, and John Lynham, “Can Catch Shares Prevent Fisheries Collapse?” Science 321, no. 5896, (2008): 1678-1681; Donald Leal, “Helping Property Rights Evolve in Marine Fisheries,” PERC Reports 28, no. 2, (2010).

4. Leverage opportunities for cooperation and shared goals.

Reintroduction need not be framed solely in terms of trade-offs. In fact, many fishing communities, tribes, and conservation groups share an interest in restoring marine habitat that supports productive fisheries. Sea otters could become a powerful ecological ally in combating purple urchin overgrazing and rebuilding degraded kelp ecosystems—especially in areas where urchin barrens have already harmed shellfish harvests.71Eger et al., Kelp Restoration Guidebook.

Reintroduction strategies could prioritize sites in proximity to such degraded areas, where conflicts may be lower and habitat restoration benefits more immediate. While positive effects on fisheries may take years to materialize, initiating reintroduction in areas with marginal shellfish value could build momentum and trust. As the benefits of reintroduction become more visible, willingness to coexist with sea otters may increase.

5. Reform key legal barriers in advance.

Congress should consider targeted amendments to the Marine Mammal Protection Act to allow for incidental take authorization for southern sea otters in commercial fisheries. This exclusion, a legacy of past management of San Nicolas Island otters, poses a significant barrier to building support among affected fishers. A narrow fix could reduce legal uncertainty and demonstrate goodwill, especially if enacted before a reintroduction proceeds.

Conclusion

Sea otters are a charismatic species whose return could help restore degraded coastal ecosystems. But if reintroduction is to succeed, it must account for the real and perceived costs it may impose on those who depend on these same ecosystems for their livelihoods and cultural traditions. While the overall net benefits of reintroducing sea otters—in ecological, social, and economic terms—may well be significantly positive, the negative impacts will likely be concentrated and therefore deeply felt by affected parties.

Done right, sea otter reintroduction would not only serve the species but also the people who live and work along the coasts of Oregon and Northern California.

The regulatory and legal hurdles to overcome in establishing a new experimental population of sea otters in Oregon or Northern California are surmountable. Navigating conflicts with affected local groups, however, will almost certainly prove to be more challenging. The Fish and Wildlife Service’s feasibility assessment recognizes these realities in its discussions of regulatory issues, socioeconomic impacts, and risks. The service and conservation groups pushing for a reintroduction must commit to mitigating its costs.

The abandoned management approach to reintroduced sea otters at San Nicholas Island alienated California’s commercial fishing interests. That history underscores the risks that remain today. If reintroduced sea otters become a liability to fishing interests and other stakeholders, then it will be a recipe for further conflict—and could even prevent a reintroduction altogether, as has happened with other species. But if conservationists can find ways to make reintroduced otters an asset to affected groups, then they could become partners in conservation of the species. With a credible commitment to cooperative conservation, it may be possible to move beyond zero-sum framing. Done right, sea otter reintroduction would not only serve the species but also the people who live and work along the coasts of Oregon and Northern California.