In 1992, a caller from a mile north of me said the Merritt family was about to cut all its land. This was the first time land bordering mine would be cut.

I had walked through this land many times. On a high hilltop, I had often stopped at the chimney of an old cabin. A large, scarred walnut tree stood next to the foundations, and in the spring, old-fashioned yellow jonquils sprouted where someone had planted them a century ago. The English poet Wordsworth stopped in a forest like this and looked on the foundations of cottages. He imagined the life there and thought about his own life. The lives gone and the slower life of the rejuvenated forest made him think of “the still, sad music of humanity.” I had several Tintern Abbeys in the forests near me, but this was my favorite. Soon, the loud, rap orchestration of humanity’s chainsaws, skidders, and logging trucks would surround it.

Cutting timber in the Piedmont hills of North Carolina usually means clear-cutting. ting turns woods that stand “lovely, dark and deep” into an expanse of naked ground, deeply rutted by skidders, punctuated with bleeding stumps, and strewn with the limbs and laps that are impossible to walk among.

The people who call me about timber cutting have seen this before and have good cause to believe that ecological Armageddon has arrived. Seeing in this case should not lead to believing. People react to a clearcut in this region the way they react to blood from a scalp wound. Usually, however, the face covered with blood does not signal a broken skull or severed brains; but clear-cutting clouds the brains of reasonable people.

Clear-cutting does not, as the Bible says of Armageddon, put an end to all things forever. To provide some perspective, a clear-cut destroys less than a fire, the eruption of Mount Saint Helens, a tidal wave, or a glacier. A clear-cut does not destroy nature itself but the nature we love and have become accustomed to seeing. It destroys, temporarily, for less than a heartbeat of geological time, the plants we love most, the trees.

Most of us are terribly sentimental about trees. I have dozens of trees in my forest that I know as individuals, and I visit them like old friends. I have an album with their pictures, some as they grew up. They serve me instead of pets, but I don’t give them names, and I don’t feed them. I don’t talk to them. They have become what they are without me—interesting shapes, enormous sizes, a mystery book of scars. I like their independence.

If someone were to clear-cut my forest, I would not only be sad but angry enough to shoot. Every day I look at the small patch of old growth across Morgan Branch in front of my house, and no matter how dark the mood I wake up in or that I carry into the day’s dusk, that little grove is as welcome as love. I understand why my neighbors call in alarm. I understand why John Muir, founder of the Sierra Club and America’s greatest hiker, could conclude his defense of old forests by writing, “God has cared for these trees, saved them from drought, disease, avalanches, and a thousand straining, leveling tempests and floods; but he cannot save them from fools.”

The Merritt who owns the land north of me is no fool. He is a plastic surgeon, a hunter, a reasonable and civil man. Like me, he can choose what he will do with his forest. The timber was worth maybe half a million dollars. Let’s say that much money put in his retirement account might earn 10 percent a year, or $50,000. If he lets the forest stand, he is paying $50,000 a year for two or three weekends of hunting. Or maybe he is paying it so that his trees can absorb carbon dioxide, which is supposed to cause global warming. Even my strongest environmentalist friends would not pay $50,000 a year for the right to birdwatch, or hike among the California redwoods or the spruce trees of Alaska’s Kodiak Island, or to lock up a few tons of greenhouse gas.

Much of the surgeon’s land was covered in pine trees that had taken over old fields and pastures. He could cut selectively and leave twelve or fifteen good seed trees for every acre. Among the hardwoods he could also cut selectively and leave an essential shade and enough trees to continue making the mast crops (nuts and seeds) that sustain deer, squirrels, and wild turkey. He could do it this way, but he would give up $100,000 or more. So he would still be paying $10,000 a year for a few weekends of hunting.

My other argument, if I wanted to argue with him, would have been that by selective cutting, the land would have a much greater appeal to the real estate market. Why would I argue that? Did I want to encourage him to sell it for development? I was better off if he clear-cut it. Even if he replanted it in pine, it would be an impenetrable thicket of saplings, blackberries, and smilax thorns for at least ten years.

The caller from the north side of Merritt’s land asked, “Is there any way we can stop him? Isn’t there some law about raping a forest like this?”

“If he cuts too close to the stream or leaves debris in the stream, he can be fined,” was my answer.

“Then it’s too late.”

“The only way to stop him would be to go to the timber sale and buy the rights to the timber,” I suggested. “Or call the owner now and ask him to sell you the rights. Then you sell the timber in a selective cut.”

“I don’t want to cut any timber,” the caller said.

“He doesn’t need the money. Why is he doing this?” The caller had a nice house, two expensive cars, and more than ten acres of land. “All of us have things we don’t need,” I said.

“Couldn’t we get the state or someone to buy it for a park?”

Now we had come down to a fundamental obstacle to saving land the way environmentalists want to do it—someone else has to pay to rescue a favored piece of land. Only the Nature Conservancy, scattered land trusts, and a few sporting groups such as Ducks Unlimited have raised money to save wildlife habitat. I told the caller that Merritt’s land was a beautiful piece of land, but it was not of great interest to the State Parks people or the Nature Conservancy.

The caller paused. I waited. “This is an environmental disaster.”

I said, “It’s not a disaster but it’s going to be ugly and years will pass before anyone can walk through that land again.” As a consolation, I explained that a clear-cut would explode with small animals—rabbits, mice, voles, moles, songbirds. Within months, those animals would attract snakes, fox, bobcats, hawks, owls, and eagles. “There will actually be more animals there after it’s cut than now,” I concluded.

The caller heard me out, waited a few seconds, sighed a four-letter word, thanked me, and hung up.

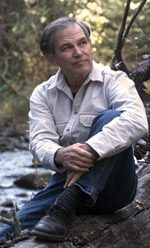

Wallace Kaufman is the author of Coming Out of the Woods: The Solitary Life of a Maverick Naturalist (Perseus Publishing), just released in paperback, and No Turning Back: Dismantling the Fantasies of Environmental Thinking (iUniverse.com, Inc.) This selection from Coming Out of the Woods was abridged with the author’s permission.