By Terry Anderson

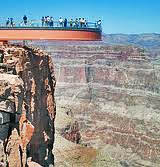

The Grand Canyon Skywalk was built by Las Vegas developer David Jin on Haulapai Indian land in the hope it would provide jobs and college scholarships for tribal members. Both are sorely needed in Indian country, where the poverty rate is twice the national average and per capita incomes are 70 percent below average.

Despite the attraction’s success, Jin and the Haulapai tribe are fighting over its future, and the battle could kill the goose that lays golden eggs. At stake are $10 million in profits held in escrow, the distribution of future profits expected to be large, and who will pay to complete the visitor center. The tribe got the upper hand in the fight when it seized the property, exercising its power of eminent domain.

The ripple effects of the seizure won’t help the business climate in Indian country, where tribal governments and courts are seen by outsiders as biased, incompetent and corrupt. Minneapolis Federal Reserve Bank President Narayana Kocherlakota says the lack of business law on reservations "has a chilling effect on business and economic development."

This problem is not new. For example, in 1953, the Jicarilla Apache negotiated a lease with Phillips Petroleum for oil and gas production on tribal land. The company agreed to pay a 12.5 percent royalty. Twenty-three years later, the tribe added a severance tax to oil and gas extraction, increasing the rate paid by Phillips to more than 20 percent. Phillips went to court arguing the tribe was changing the terms of the contract. Eventually, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in favor of the tribe on the grounds that the tribe was a sovereign government exercising its power to tax.

Whether this ruling was "favorable" to Indians in the long run, however, is questionable. The tribe saw immediate gains when it took in an additional $2 million from oil company profits. But since then, energy companies have been less willing to invest on reservations where this might happen again.

Congress tried to improve the reservation legal climate in 1958 by declaring more than 30 reservations to be "lawless" and requiring them to resolve disputes in state courts. The effects on economic growth are clear. Per capita income in 1999 was 34 percent higher for reservations under state jurisdiction and income growth between 1969 and 1999 was 26 percent higher.

Because Montana was not one of those states, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that Montana state courts lacked jurisdiction to enforce payment of a debt owed by a Blackfeet Indian to a non-Indian store owner on the reservation. This led a Montana Supreme Court justice to opine that the result "was to dry up credit sources throughout the state to responsible Indian citizens."

A banker from Billings, Mont., near the Crow reservation, told Forbes, "We take on such a huge extra risk with someone from the reservation. If I knew contracts would be enforced, then I could do a lot more business there."

Some tribes are improving their governance and judicial systems. They are adopting uniform commercial codes, better training their judges and submitting disputes to binding outside arbitration, as successful tribal casinos do.

Such improvements are crucial if tribal governments are to stop killing the capitalist goose and pull Indians out of poverty.

Terry Anderson is the John and Jean DeNault senior fellow at Stanford University’s Hoover Institution and executive director of the Property and Environment Research Center in Bozeman, Mont.