At a time when there’s a spotlight on America’s richest 1%, a look at the country’s 310 Indian reservations—where many of America’s poorest 1% live—can be more enlightening. To explain the poverty of the reservations, people usually point to alcoholism, corruption or school-dropout rates, not to mention the long distances to jobs and the dusty undeveloped land that doesn’t seem good for growing much. But those are just symptoms. Prosperity is built on property rights, and reservations often have neither. They’re a demonstration of what happens when property rights are weak or non-existent.

The raw quality of the land is not that much different, it’s the amount of investment in that land that’s different.

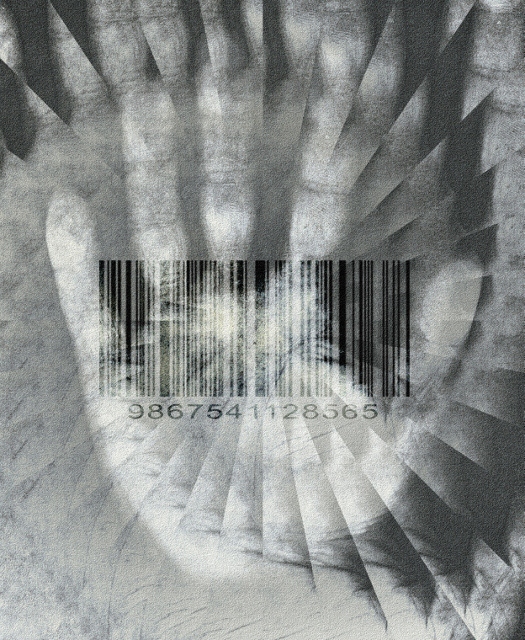

The vast majority of land on reservations is held communally. That means residents can’t get clear title to the land where their home sits, one reason for the abundance of mobile homes on reservations. This makes it hard for Native Americans to establish credit and borrow money to improve their homes because they can’t use the land as collateral—and investing in something you don’t own makes little sense, anyway.

More than a third of the Crow reservation’s 2.3 million acres is individually owned, and the contrast with the communal land—often just on the other side of a fence—is stark, as Google satellite maps show. Terry Anderson, president of the Property & Environment Research Center in Bozeman, Montana, coauthored a study showing that private land is 30—90% more productive agriculturally than the adjacent trust land. And this isn’t because the land is better: A study of 13 reservations in the West put 49% of the land in the top four quality classes, while only 38% of the land in the surrounding counties was rated that highly. For the Crow reservation, 48% of the land made the top four classes; only 33% of the adjacent land did. “The raw quality of the land is not that much different, it’s the amount of investment in that land that’s different,” he says.

Canada faces the same issues with its 630 bands—as tribes there are called—but thanks to the effort of a dogged reformer, there’s a push to allow reservation land to be privatized. Manny Jules, a former chief of the Kamloops Indian band in British Columbia, is lining up support for the First Nations Property Ownership Act, which would allow bands to opt out of the government ownership of their land and putit under tribal and private ownership. Reserves would become new entities that would have some of the powers of municipalities, provinces and the federal government to provide schools, hospitals and other services, and to enact zoning laws. He expects that the bill will be introduced in Parliament in 2012 and is confident of approval by the end of the year. What’s forcing the issue is an acute housing crisis on the reserves. Without private property rights, little housing is being built even as the Indian population grows, and the Assembly of First Nations estimates that the reserves need 85,000 new houses immediately; the government is building only 2,200 a year.

When you don’t have individual property rights, you can’t build, you can’t be bonded, you can’t pass on wealth.

“Markets haven’t been allowed to operate in reserve lands,” says Jules. “We’ve been legislated out of the economy. When you don’t have individual property rights, you can’t build, you can’t be bonded, you can’t pass on wealth. A lot of small businesses never get started because people can’t leverage property [to raise funds]. This act would free our entrepreneurial spirit, but it’s going to take a freeing of our imagination. We have to become part of the national and global economies.”

For the bureau and other narrow interests, staying with the convoluted system of land ownership is safer than improving property rights.

But even if Jules succeeds, there is no reformer like him in the U.S. to lead the charge here. Any effort at land reform must go through the Bureau of Indian Affairs. But the bureau, originally part of the War Department and one of the federal government’s oldest agencies, isn’t about to pave the way for its own demise by signing off on an effort to privatize reservation land. The bureau faced this situation before: Under the 1887 Dawes Act, land could be allotted to individual Indians, but by 1934 so much land had been privatized that Congress reversed course and communal tribal property was back in favor. “Allotment threatened the bureau so it had an incentive to end the process,” says Dominic Parker, an economics professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. In any event, tribal councils wouldn’t be keen to give up the patronage and power that controlling vast amounts of land gives them. And the $2.5 billion a year that Washington spends on programs for Native Americans is a powerful deterrent to change. “For the bureau and other narrow interests, staying with the convoluted system of land ownership is safer than improving property rights,” he says. The bureau declined to comment.

Plus, there are practical issues. Any Indian who didn’t win clear title to land by 1934 was left with a fractional share of the reservation’s land held in trust. With every generation, each share was divided among more family members and today hundreds of people may have a partial claim to one share of trust land. Often there are no records of where many of these people are. In the Crow reservation, 1 million of the 2.3 million acres are held in trust for such individuals. The Dawes Act created another problem: The non-Indian owners of privatized land in a reservation have always faced legal questions over whether they come under the jurisdiction of the tribal authority. The checkerboard pattern of private and trust land in some reservations make it tough for tribes to provide services and do land-use planning.

Anderson puts the choice for tribes in sharp terms. “If you don’t want private ownership, and want to stay under trusteeship, then I say, ‘fine.’ But you’re going to stay underdeveloped; you’re not going to get rich.”

The problems of the reservations go well beyond residents not having the right incentives to upgrade their surroundings. With some exceptions, even casinos haven’t much benefited the several dozen reservations that have built them. Companies and investors are often reluctant to do business on reservations—everything from signing up fast food franchisees to lending to casino projects—because getting contracts enforced under tribal law can be iffy. Indian nations can be small and issues don’t come up that often, so commercial codes aren’t well-developed and precedents are lacking. And Indian defendants have a home court advantage. “We’re a long way from having a reliable business climate,” says Bill Yellowtail, a former Crow official and a former Montana state senator. “Businesses coming to the reservation ask, ‘What am I getting into?’ The tribal courts are not reliable dispute forums.”

Putting reservations under the legal jurisdiction of the states, and facilitating better legal codes and better functioning court systems, would assist tribes in developing their land.

Some tribes are taking steps to improve their legal structures, such as adopting new commercial codes to make their laws more uniform. Over a 30-year period, reservations that had adopted the judicial systems of the states where they’re located saw their per capita income grow 30% faster than reservations that didn’t, according to a study by Anderson and Parker. A separate study by Parker shows that Native Americans are 50% more likely to have a loan application approved when lenders have access to state

courts. “Putting reservations under the legal jurisdiction of the states, and facilitating better legal codes and better functioning court systems, would assist tribes in developing their land,” says Anderson.

We have 9 billion tons of high-quality coal sitting under the reservation, going largely untapped. Natural gas, too. Potential development galore, but that potential is never realized.

“Privatizing land is fine but it falls far short of the answer,” says Yellowtail. “Our people don’t understand business. After 10 or 15 generations of not being involved in business, they’ve lost their feel for it. Capitalism is considered threatening to our identity, our traditions. Successful entrepreneurs are considered sell-outs, they’re ostracized. We have to promote the dignity of self-sufficiency among Indians. Instead we have a culture of malaise: ‘The tribe will take care of us.’ We accept the myth of communalism. And we don’t value education. We resist it.”

But Yellowtail believes that the situation is improving. He says there are more entrepreneurs than 20 years ago as networks of Native American business people have sprung up in Montana and elsewhere. “We have to start with micro loans, encouraging small businesses. Then we have to make it okay to leave the reservation because the most successful are going to want to branch out. Entrepreneurs are going to have to stick their neck out, be a role model. We Indians are going to have to do it.”