Captain Moses Harris led his band of troopers into Yellowstone National Park in 1886 when the park—and the national park idea itself—faced its greatest threat yet.

In response to allegations of corruption, Congress had recently cut the meager funding it provided to the park. Poaching was rampant. Tourists carved off huge sections of the fragile travertine thermal features that were the heart of the attraction. Wildfires, often started by the Shoshone hunters that lived in the park, raged along the Gardiner River.

Harris ordered his men to fight the fires, capture the poachers, and stop the vandalism. He and the officers who followed him developed the skills and expertise necessary to manage a national park, including firefighting, road building, campground development, and concessions management. The Army laid the foundation for the federal government to retain large tracts of public land, not just in parks but eventually in national forests, wildlife refuges, and rangelands.

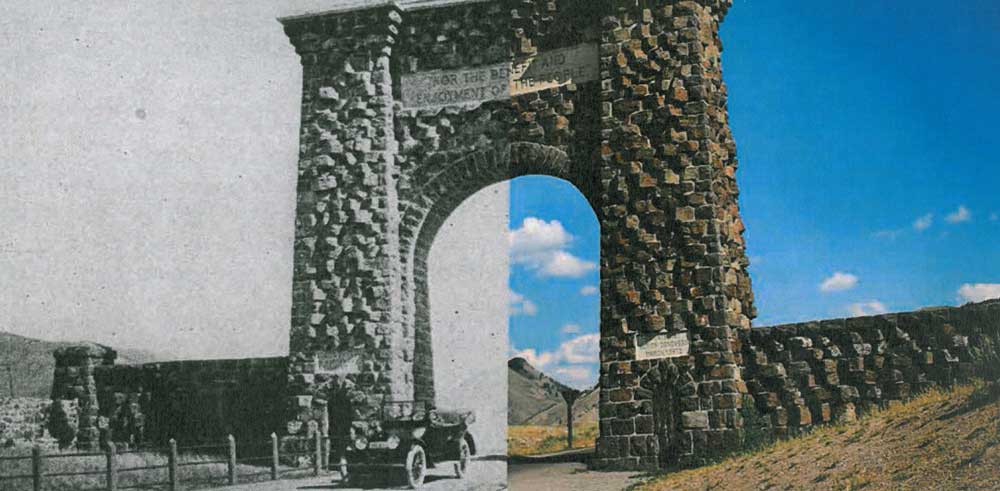

The federal government’s success managing these lands has a mixed record, but the preservation of national parks is considered by many to be “America’s best idea.” Harris and the U.S. Army saved the national park idea, and the Army managed Yellowstone and other national parks until the National Park Service was established in 1916, nearly one hundred years ago today.

LAST SUMMER, I WALKED UP THE HILL behind Mammoth Hot Springs Hotel to the old road where Captain Harris entered the park. Much was the same as what he likely saw. The smell of sagebrush mixed with sulfur and the giant white-rocked hot springs steamed and bubbled.

But the valley was filled with people, cars, buses, a hotel, houses, stores, a gas station, and the stone park headquarters. Elk grazed on Kentucky bluegrass, a non-native grass, as rangers kept visitors at a safe distance. It looked remarkably similar to how I first saw it in 1985, and for my grandson Alex, it presented the same mix of wonderment, entertainment, and education.

The national park experience can be a personal one. For those of us who live near Yellowstone and other western parks, it’s an annual or even monthly event that carries with it all of our own attitudes and interests. As America’s best idea, parks are closely tied to our own patriotic pride, our civic ties to our history and our national identity. So, for me, the chance to pass on the experience to my grandchildren means that the National Park Service has done a pretty good job.

The fact is that Yellowstone today is as great an experience for me or better as it was in 1985, in part because the National Park Service and Congress have listened to free market environmentalists.

More than 30 years ago, a group of free market economists began examining alternative ideas for addressing public land management and other environmental issues. These economists studied the ways in which property rights and markets could improve the environment, but they recognized that many public lands were likely to remain in public ownership, partly because of their unique history.

Instead, these free market environmentalists, as they became known, provided a path to improve national park management by harnessing the forces of private enterprise within the public land system. That includes using fees, incentives, and other market tools.

The most important idea was for individual parks to retain most of the fees they collected. This helps parks become more self-sufficient, less reliant on Congress and politics, and more nimble to steward and care for park resources. Fortunately, Congress listened, and today national parks keep at least 80 percent of the fees they collect. This gives each park the incentive to develop a fee program that meets its needs.

The other ongoing problem national parks face is the $11.5 billion maintenance backlog. Congress does not appear eager to make that up soon. But Yellowstone has found a market approach to addressing some of its backlog by writing into its contracts with concessionaires to pay for capital maintenance over the course of the contract.

The National Park Service is also increasingly tapping into public-private partnerships, which cause many to worry that corporate interests will take precedence over the public interest. But it’s clear the National Park Service has been able to better serve its visiting public by allowing concessionaires to mimic certain private destinations and tap into the private sector’s entrepreneurial spirit.

Such efforts are underway in parks such as Yellowstone. Superintendent Dan Wenk has welcomed corporation donations and growth in the park’s charitable foundation to offset cuts by Congress. He is also pushing for higher, more effective entrance fees. His renegotiated contract with the park’s concessionaire aims to direct funds to capital investment, long underfunded by Congress.

AS THE NATIONAL PARK SERVICE PREPARES for its centennial celebration in 2016, the agency is looking to address the challenges of the next 100 years—and there are many. Climate change is transforming the ecosystems and indeed the very scenery the parks were established to protect, such as Glacier National Park’s disappearing glaciers. Invasive species force changes in the food chain, and their effects cascade through the landscape.

Younger people spend less time outside, let alone hiking, horseback riding, wildlife watching, or camping. These are the next generation of national park visitors, and if they are indifferent then the parks become irrelevant. Yet the sheer growth in the world’s population is bringing increasing numbers of visitors to the parks, requiring more services, more maintenance, and more funding.

Despite the infusion of free market ideas to park management, the United States drew the line between the public and private interest back in the 1880s when Congress kept the Northern Pacific railroad from taking control of Yellowstone’s most prized features. The railroad played a critical role in the legislation that established Yellowstone and saw the parks as both destinations to promote travel and also key to their brand.

The Canadian Pacific railroad played a similar role in the creation of the national parks in the Canadian Rockies, only it retained far more control than American railroads because it owned its hotels and much of the land in communities inside the parks like Banff. Hotels like the Chateau, Banff Springs in Banff National Park, or the Jasper Park Lodge are as much a tourist attraction as the parks themselves. When the Canadian Pacific sold off the lodges, another corporation got control of portions of these national treasures in a way that so far cannot be done in America’s national parks.

Inherently, our national park tradition provides a political barrier to sweeping corporate influence over our crown jewels. But as the free market environmentalists at PERC demonstrate, that doesn’t mean free market ideas can’t continue to make “America’s best idea” even better.