I have just returned from a 10-day trip to the Yucatán Peninsula in Mexico where I visited Cozumel, Playa del Carmen, and Cancun. When I planned the SCUBA trip, I expected it be a relaxing vacation. However, ever since starting to work on market-based solutions to invasive lionfish, I just could not help but turn a “vacation” into a hands-on research project.

Unfortunately, invasive lionfish have become a prevalent species in Cozumel. According to my divemaster, who works for the company Dive Paradise, local dive operators have bonded together informally to begin addressing the lionfish invasion. Divemasters carry simple spear systems with them on each dive. When a lionfish is spotted, it is killed. Of the 25-30 dives I completed, lionfish were seen on about 10 of the dives, only in the shallower reef areas (45-60 feet). After it is speared, a lionfish’s spines are cut off and the fish is fed to eels or other fish. “Tourists” are not supposed to shoot the lionfish, for fear of someone being stung in the process, but our divemaster let one of the people on our boat, Eric, try his hand at the lionfish management process. According to Eric, the success of a shot really relies on the equipment being used. One spear he tried had a guidance mechanism to shoot the spear straight, whereas the other did not. Of the lionfish Eric went after, he successfully killed about half of them.

One afternoon our divemaster wanted the lionfish for dinner, so he kept approximately five of them for later feasting. While I was impressed with his interest in eating the fish, despite potential ciguatera concerns (a foodborne illness from eating certain reef fishes), I was very disappointed when he would not kill a lionfish that I found. His response was that he knew that the lionfish would be there the next time he went to the dive site, and he wanted the fish to get a little bigger so there was more meat for him to eat. This is part of the challenge with trying to get people to target lionfish; we do not want people to wait to harvest invasive lionfish in the hope that they will get bigger. The process of a lionfish growing means that it has eaten more of the critical reef species that we are trying to protect.

In Mexico, some species are protected, more from local agreement than law (based on my observations) while others are hunted (whether or not they should be). For example, while the local divemasters have started capturing/killing the lionfish, I saw no evidence yet that other locals had taken up the cause. One morning we visited the “mercado” (market in Spanish), and I was sadly disappointed to see plenty of other reef fish awaiting sale, but no lionfish. However, it seems to be the rule that sea turtles and whale sharks are protected. I saw multiple sites where sea turtle nests were marked with stakes so that people would avoid walking over them. In Cancun, hotel chains such as the Westin have formal protection schemes in place where eggs are collected, marked with the date of laying, and put into a roped off area for protection before hatching. Nonetheless, I saw or heard of divemasters being what I would consider too “hands on” with sea turtles, trying to physically prevent their movement by blocking where the turtles were trying to swim. Whale shark tours cost about $200 US a day, and locals are highly protective of them, probably for economic reasons. According to one local, sometime last year a fisherman killed about nine whale sharks. The incident resulted in an uproar and more action to formally protect whale sharks.

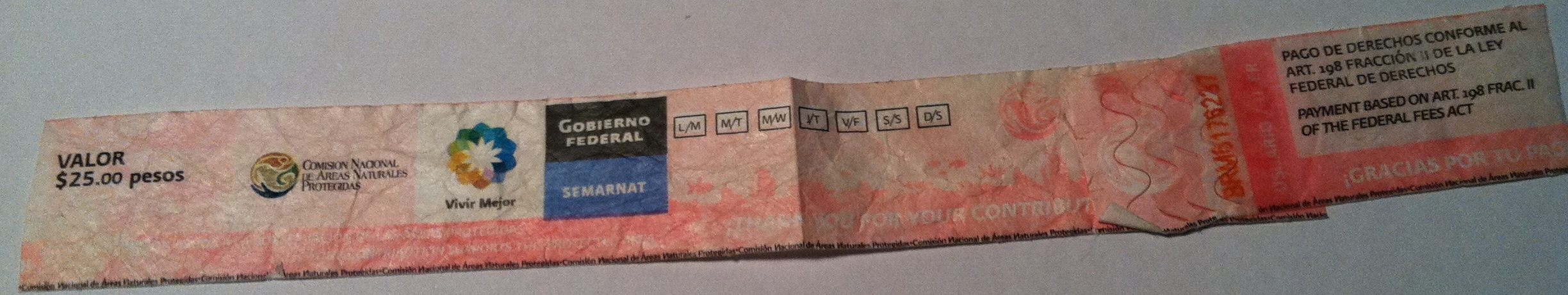

According to one website, “most diving sites in Cozumel are located within the Cozumel Reefs National Marine Park (Parque Nacional Arrecifes de Cozumel), a protected underwater environment covering 29,000+ acres. A voluntary $2.00 US donation/fee from divers was implemented to fund the conservation program. The Mexican government declared a National Marine park on July 19, 1996…the environmental, natural resource and fishing Secretariat SEMARNAP, administers the park.”

I spoke with several local shopkeepers, all of whom tried to sell me gifts that definitely came out of marine reserve areas, including shark jaws, and necklaces with either carved pieces of black coral or shark teeth that were collected by killing sharks. When I asked where the coral and shark teeth came from, the locals were not shy about saying that they simply fished the Cozumel Reefs National Marine Park areas, usually at night to avoid detection. They also thought that the fee structure was a complete joke. One shop owner in Cozumel reported that only one gentleman had the exclusive right to collect as much black coral as he wanted, others were prevented from doing so. Needless to say, the gifts I brought home from the trip were limited to photos and t-shirts.

To me, Cozumel Reefs National Marine Park is, unfortunately, an example of an attempted property rights scheme gone badly. Rather than using the funds collected to address marine environmental problems, it seemed that nothing was being done to protect the reef and that it was simply a “paper park” (legally protected, but no enforcement). This was in sharp contrast to four dives I did in the Playa del Carmen area in underwater cavern/cave systems known as “a cenote.” While some of the cenotes are on public lands, many are on privately-owned lots. According to our divemaster from Dive Shop Mexico, some cenotes properties are communally owned by up to 180 families, and any property with a cenote on it sells for about 10 times more as one that does not. The private cenote I visited had a clear set of rules that were enforced, and no garbage was visible on the dives.

Overall, my trip to Mexico was very enlightening. It presented some hands-on experience with capturing lionfish, showed me the challenges associated with marine parks, and gave me some great ideas for how education and more formalized property rights schemes could incentivize locals to save, rather than destroy, their reefs.

Originally posted at Gaia Endeavors. Read more about lionfish from Linda Platts in PERC Reports.