“When you start to build houses and stop growing cotton, you’re going to save a lot of water.” With that quip, Kim Schonek sums up how Arizona’s population has managed to blossom in the middle of the arid West while reducing its water use at the same time. Since 1980, the population of Phoenix has more than doubled, yet total water use has decreased by about one-third.

Some back-of-the-envelope math helps demonstrate how: An acre of cotton needs about 3 acre-feet of water, or roughly the same amount of water to meet the needs of six average Arizona families. If 100 acres of cotton fields were converted into subdivisions with quarter-acre lots, water use would decline by roughly a third.

But even in rapidly growing western regions such as central Arizona, not all crop fields are going to become suburbs anytime soon. So a few years ago, Schonek, a project manager at the Nature Conservancy, started to think about ways to conserve water in a place where farming persists but water demand from recreationists and other users is growing. “And that’s actually a really hard question,” she says.

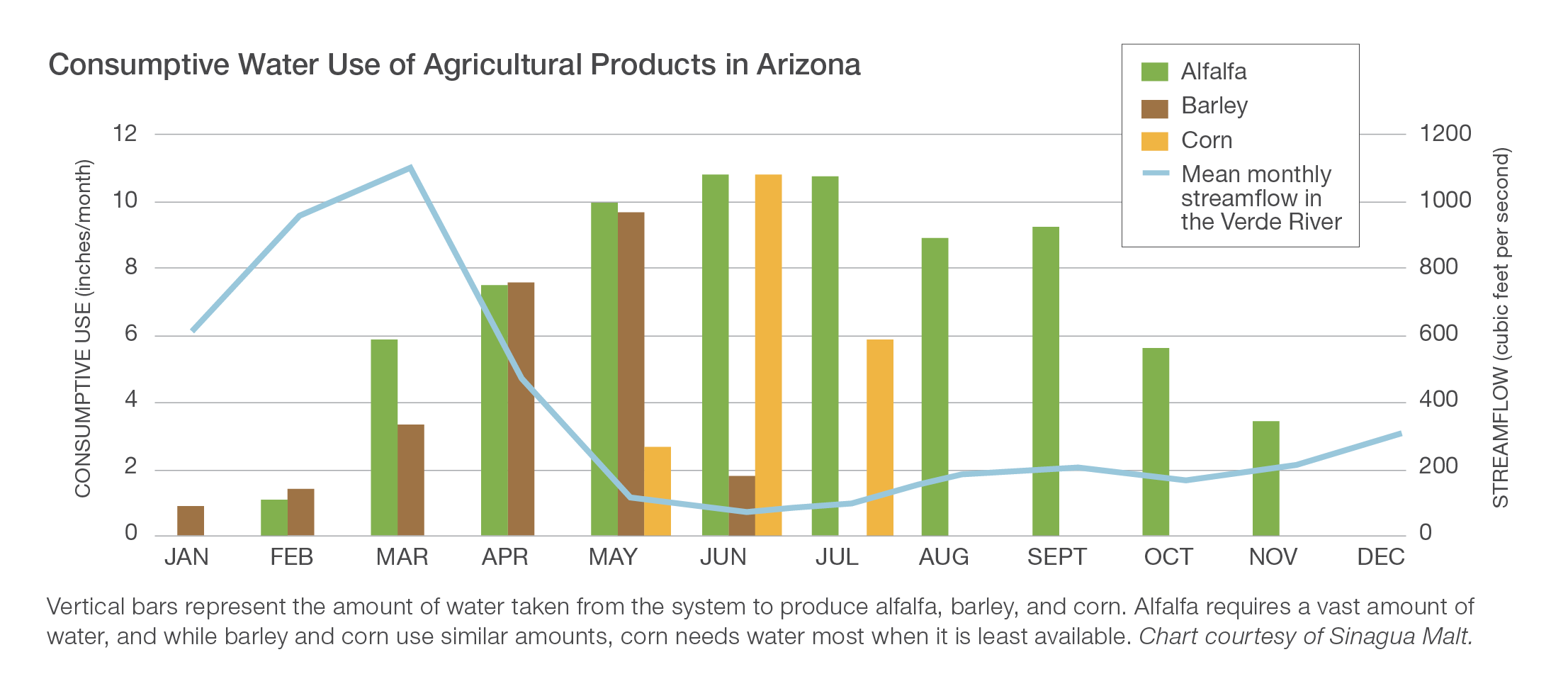

A nascent project she’s helped launch has yielded one clear answer, at least in the green valley that the Verde River snakes through on its way to Phoenix and the populated center of the state: beer drinkers. Last spring, the first commercial malting facility opened in Arizona, a state with 96 craft breweries that collectively do $1 billion of business each year. Schonek helped put together the pieces for the effort, which conserves water by encouraging farmers in the Verde to grow barley in place of more water-intensive crops like alfalfa and corn. But it required some creative thinking, and the creation of an entirely new local market.

When it comes to water in the West, every drop matters. The region is home to seven of the 10 fastest-growing states in the country, a trend partly driven by domestic migration to expanding economies in places with scenic natural amenities. But amidst their growth, western communities have had to deal with the pains and, often, clashes that come from the reality of water scarcity. As cities draw more and more water, much of it comes at the expense of sectors like agriculture and mining, creating tensions. A salient and controversial example is the “buy and dry” trend of municipalities purchasing farmlands just for the water rights that come bundled with them, leaving the fields to fallow as they transfer water capacity to residential customers.

Arizona’s population has managed to blossom in the middle of the arid West while reducing its water use at the same time. Since 1980, the population of Phoenix has more than doubled, yet total water use has decreased by about one-third.

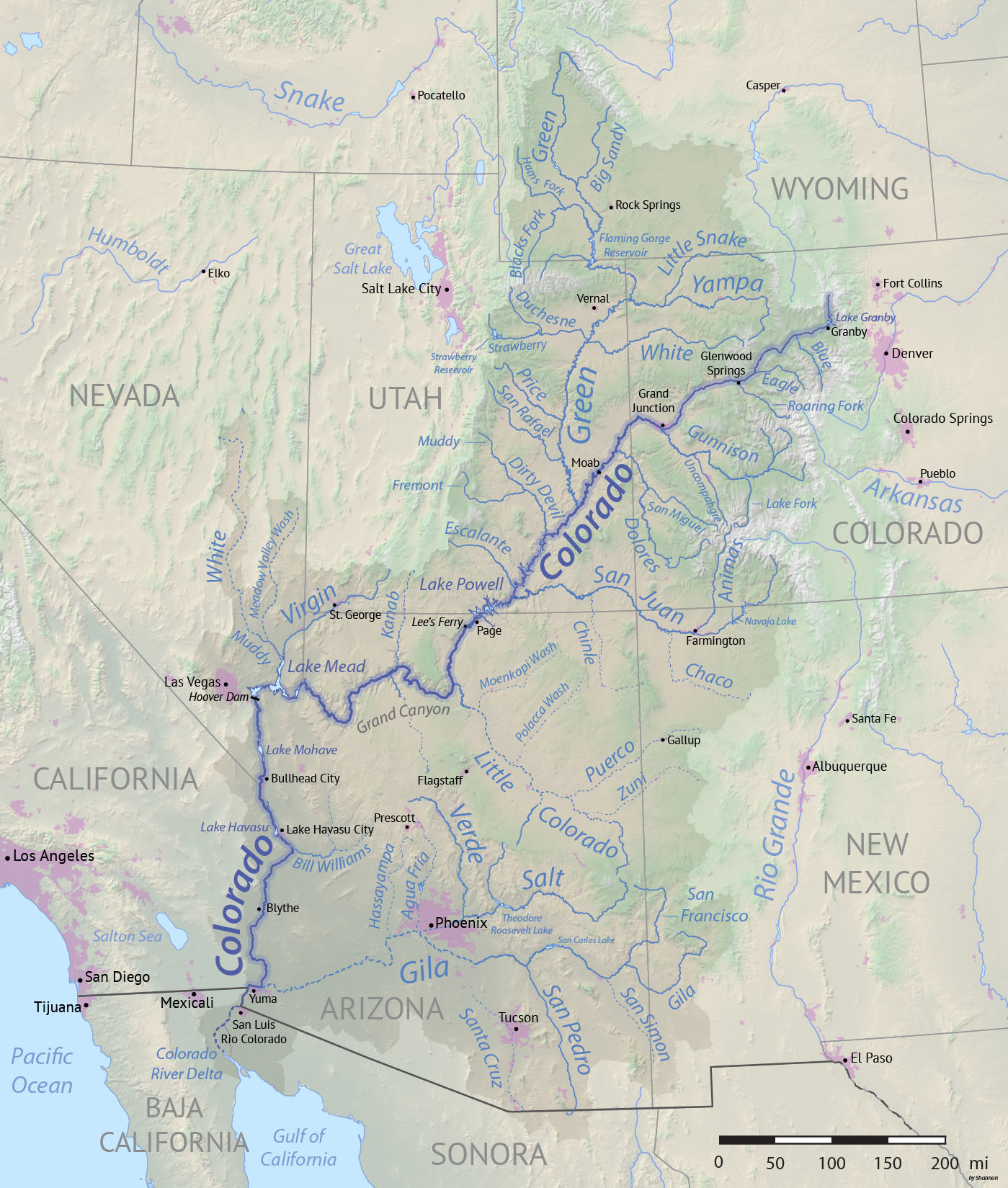

Competition over water is probably most apparent in the Colorado River Basin, which supplies water to 40 million people across seven states and two countries. Now, with a potential shortage looming for some users who rely on the river, states are attempting to deal with the realities of sharing this prominent but dwindling water source. The burgeoning New West will demand innovative solutions that can do more with less, find ways for competing user groups to cooperate and exchange, and somehow get water to all of the people who need it. In central Arizona, the Verde Valley shows how one tiny piece of this western water puzzle might fall into place.

First Stop: Verde

Standing at the bank of the Verde River in the middle of October, the water is running high, fast, and brown. Two kayakers put in at a river access point just outside of Camp Verde, a quiet town of 10,000 in the Lower Sonoran Desert about an hour and a half north of Phoenix. Eighteen miles of river lie within the town limits, bringing irrigation to approximately 6,000 acres of farmland here. That amount of irrigation means the river flows much lower during the dry summer months. While kayaking a few summers ago, Schonek and her husband ran aground so much that their journey involved as much hiking as paddling.

In 2015, the Nature Conservancy began working with Verde farmers to improve irrigation efficiency so that more water would remain instream. But Schonek wanted to do more to increase flows, which would benefit anyone and everything that relies on this tributary of the Colorado River: fish and wildlife, recreationists, and downstream water users. And while the organization had also tried schemes that paid farmers annually to curtail irrigation and leave water in the river, it recognized the need for longer-lasting solutions.

Most of the valley’s agriculture consists of alfalfa and corn, crops that not only need a lot of water but need it during the driest months of the year. Schonek thought if she could get some of the farmers she was working with interested in shifting a portion of their production to other crops, it might help restore the dwindling summer flows. Barley seemed like just the ticket.

“Small grains are awesome,” says Schonek, “because you don’t need as much water, and they’re off season.” Barley needs water in the relatively wet spring, when streamflows are high, but doesn’t need much in the low-flow summer season. Less demand to divert irrigation water during the summer means more gets left in the river for fish, wildlife, and kayakers.

Most barley, however, gets sold as animal feed, a commodity market that’s usually not exciting or remunerative enough to entice farmers already knee deep in corn and alfalfa. But if you’re a farmer looking for a lucrative market for barley, there’s an alternative route these days: craft beer. A high-quality barley malted for IPAs, saisons, and other distinctive beers could be sold at a premium, particularly if it could be marketed with an Arizona-grown story as well.

When it came to getting farmers on board, it also helped that the Nature Conservancy offered backing akin to crop insurance at the beginning of the project, covering much of the risk associated with it. Hauser and Hauser, a six-generation family-farming operation, planted 15 acres of barley in 2016. That grain was malted in Texas to positive reviews and served as the proof of concept. “If we can switch crops and spread out our risk so it makes it easier to manage and still make a profit, we’re in great shape,” says Kevin Hauser, owner of the farm. “It’s good for the river and farming.”

The following year the Hausers converted 144 acres of their cropland to barley, with the hopes of eventually sending their grain just a few miles down the road. “But we didn’t have a malt house,” Schonek says. That was the missing link to creating a local market that would allow farmers to sell to Arizona brewers at a premium. So with partial backing from donors Intel and Pepsi, the Nature Conservancy helped launch Sinagua Malt, which opened earlier this year.

“The purpose of Sinagua Malt is river conservation,” says Chip Norton, who retired after a career in construction working on watershed development projects and co-founded the malt house. Norton is an investor in the venture and manages it pro bono. In a nutshell, Sinagua Malt (sin- for “without,” –agua for water) provides a market that encourages farmers to use water in the spring when it’s plentiful rather than in the summer when it’s scarce. “It has to make economic sense for farmers,” Norton stresses. “That’s the starting point. And it also has to make good craft beer for brewers. But our purpose is river conservation. It’s really about flows—our summer base flows are really getting bad.”

A few years ago, Norton and a friend helped launch Many Rivers Brewing Company in Grand Junction, Colorado, which donates its profits to organizations working on river conservation. So he naturally liked the idea of helping start a financially sustainable enterprise that gives back to the river in the Arizona town where he and his wife settled. “This is a scale that people can relate to,” says Norton. “If you go to your local brewery and hear about how the beer you’re drinking is helping river conservation, you can personally relate to that.”

In the southeastern outskirts of Phoenix, you can do just that. Arizona Wilderness Brewing, dubbed the “world’s best new brewery” after opening in 2013, buys much of Sinagua Malt’s production. A sandwich board on the taproom patio displays the logo of the malt house, advertising the brewery’s link to local grain. Carly Jones, a marketing coordinator, says the switch to a local, small-scale malt raised their costs—and consequently, their prices—but it was worth it not only to the owners of the brewery but also to its patrons, who value the river-conservation ethos. In other words, the beer market is speaking up for rivers.

In that same vein, Schonek believes that if you want to change the way farmers use water, you should look to agricultural markets. “Ag will always respond to the market conditions,” she says, “because farmers will grow what will make them money,” a truism borne out by the malting effort. “Everybody would like to grow barley next year,” she says, “but we don’t have any more capacity at the malt house right now.” The goal is to eventually ramp up to 600 acres of barley production, which may not seem like a vast expanse but is a meaningful amount for the Verde—one-tenth of the valley’s irrigated farmland. According to the Nature Conservancy, that would keep 200 million gallons of water in stream during summer, enough water for more than 1,200 average households. And any water that stays in the Verde ends up in Phoenix, where the waterway runs into the Salt River, and where it becomes subject to the longstanding push and pull of the agricultural and municipal water demands of the nation’s fifth-largest city.

Next Stop: Salt

Outside Arizona, there’s a popular view that Phoenix is “the world’s least sustainable city,” as New York University social scientist Andrew Ross put it in his 2011 book, Bird on Fire. Christa McJunkin takes issue with that notion. “Asking if you have enough water is like asking if you have enough money saved for retirement, ” she says. “It depends on how you want to live.”

McJunkin is director of water strategy at Salt River Project, the largest supplier of water to the Phoenix metropolitan area and one of the oldest Bureau of Reclamation projects in the country. She notes that the common mistake made by many people is to obsess over precipitation levels. Phoenix averages just 8 inches of annual precipitation, but that’s only one part of its water portfolio. While the city is in the middle of a desert in the fastest-growing county in the nation, it has multiple sources of water: surface water from the Salt and Verde Rivers, groundwater from aquifers, and water carried from the Colorado River via a 336-mile canal system. And while each source is susceptible to shortage, each is independent from the others, making Maricopa County’s water supply more resilient than many outsiders might assume.

A 2012 study by University of Florida researchers did not rate the city of Phoenix particularly high in terms of its water availability—202nd out of 225 large cities. But its vulnerability rating—“medium”—wasn’t nearly as dire as critics contend, and, perhaps surprisingly, the metro ranked better than some notable urban centers in much wetter climes, including New York City and Chicago.

McJunkin points out that Phoenix uses the same amount of water today as it did in 1957, despite the fact that its population has increased fivefold since then. That increase in efficiency is largely due to replacing acres of cotton and alfalfa with housing. But the savings is also a product of better technology and conservation practices throughout the metro area, including high-efficiency plumbing, expanded recycling of wastewater, pricing schemes that charge more for water during summer, and incentive payments for households that ditch lawns in favor of low- or no-water “xeriscaping.”

“We basically plan for it to be dry,” McJunkin says, “and if it’s wet we adjust for that.” She points out that curtailing water use preemptively so that you don’t run out entirely is a much different prospect than having to tell customers, “We actually don’t have water to give you.” But that type of forward-looking management is a far cry from the way water is managed in much of the West, particularly when it comes to its most prominent source, the Colorado River.

Last Stop: Colorado

When the Salt River leaves Phoenix to the west, it flows into the Gila River and eventually down to Yuma, where it spills into the Colorado River. A 1922 compact, along with subsequent agreements and court rulings, governs the Colorado River and apportions its water to the seven states that lie in its basin. But as McJunkin notes, the water law of the Colorado is “completely use it or lose it,” meaning there’s little to no incentive for states to conserve. Arizona perhaps demonstrates this principle better than any other—for decades, the state has worried that California will usurp part of Arizona’s allocation if it doesn’t show that it’s using its full water budget.

The incentive to use rather than conserve along the Colorado is especially detrimental given a decades-old mistake that underlies the law of the river: There’s more water on paper than there is in the river. The law apportions 16.5 million acre-feet of water, yet modern research shows there’s more like 12.5 million acre-feet in the river. The original estimates of available water were based on “two of the wettest decades in 500 years,” as the Bureau of Reclamation notes. “Until recently, this overestimation was of no issue, since many states were not using their entire allotment. However, increasing population and more than a decade of drought have made this issue a real concern.”

This overestimation has created challenges throughout the basin but particularly among the lower-basin states: Arizona, California, and Nevada. Arizona’s apportionment of the river is 2.4 million acre-feet, and about half of that is carried to residents and farmers in the populous middle of the state by the Central Arizona Project, the 300-plus-mile canal whose 20-year-long construction began in 1973. The logic was to use Colorado River water to reduce out-of-control groundwater pumping. One stipulation of getting federal funding for the project was for the state to bring that pumping under control, which its 1980 Groundwater Management Act helped do. The other stipulation was just as enduring: Arizona had to accept junior priority relative to California for Colorado River water.

The groundwater act and the state’s water law more generally has spurred desert cities to “continually plan, innovate and develop strategies to make sure water is always available when you turn on your tap,” as Warren Tenney, executive director of the Arizona Municipal Water Users Association, puts it. The association’s membership includes 10 large Maricopa County municipalities that represent more than half the state’s population. Cities and water agencies can make what is essentially a temporal trade, banking water underground today in exchange for using it in future times of need. “Our desert cities understand that water supplies are never a certainty in an arid state,” Tenney writes. “Storing water is just one way the [association] cities prepare to protect their residents and businesses in the Valley of the Sun.”

In an arid state, planning carefully for the future is a must even in the best of times. Today, in the midst of a nearly two-decade drought in the West, water management seems to be coming to a head in Arizona and throughout the Colorado Basin. The Bureau of Reclamation released a report in August that projects the first ever federal shortage declaration for the lower basin by 2020—a declaration triggered if the water level of Lake Mead falls below 1,075 feet—which would trigger cuts for Arizona and Nevada.

In October, the three lower-basin states revealed their drought contingency plan, a voluntary agreement to cut usage now in an effort to avoid an even more dire shortage declaration in the future. Arizona would take the largest cuts, and how those cuts get apportioned within the state is a point of great contention, particularly among some farmers. And the challenge may only get more difficult. Recent climate and hydrology modeling suggest that in coming decades the Colorado River’s flows could decrease by 20 percent compared to the 20th-century average.

More with Less

John Fleck, a long-time reporter for the Albuquerque Journal and now director of the Water Resources Program at the University of New Mexico, has spent years contemplating the Colorado River conundrum. In Water is for Fighting Over: and Other Myths about Water in the West, Fleck’s 2016 book about the basin, he writes: “Within the network of state and water-agency representatives working on Colorado River Basin problems, there is a clear recognition that eventually some sort of ‘grand bargain’ will be needed that finds a way to reduce everyone’s water allocation. To keep the system from crashing, everyone will have to give something up.”

Given that reality, it’s clear that western residents, farmers, and communities will have to learn how to do more with less. That’s why innovative projects like Sinagua Malt will become more and more crucial in the New West. While it may be small in scale, the operation keeps water in the Verde River, where it—theoretically, at least—can then make its way to Phoenix and eventually to the Colorado.

“Ultimately, anything that helps in the Colorado River Basin is a big help for Arizona’s water portfolio,” says the malt house’s Chip Norton. The linchpin of the malting effort is the fact that it makes economic sense for farmers. Barley has proven economically feasible in the Verde, and it might even provide more reliability relative to boom-and-bust alternatives like corn.

The challenge of managing the water available from the Colorado River may only get more difficult. Recent climate and hydrology modeling suggest that in coming decades the river’s flows could decrease by 20 percent compared to the 20th-century average.

If everyone will have to give up something to reduce aggregate water consumption, the question is how it will happen. The allure of top-down regulations like mandatory usage restrictions will likely prove irresistible to some politicians. But bottom-up, market-based approaches hold the potential to curtail consumption through cooperation. “I like the approach of looking for market solutions,” Norton says. “Farmers are business people first and foremost, and I think it’s hard in the long-run for conservation to work if you don’t have the business community on your side.”

The answer to water management in the Colorado Basin likely won’t be establishing malt houses up and down the river and its tributaries. Local context will dictate local solutions. But creative entrepreneurs and mutually beneficial exchanges can certainly be part of helping change incentives in ways that conserve water, notwithstanding the institutional challenges that come from the legal framework that governs the river.

Doing more with less will take many different forms across the West. But enough small efforts to conserve water molecules in tributaries like the Verde can ultimately produce big impacts, helping ensure the Colorado River’s water remains available to millions of people downstream. Meeting the water challenges of the New West will require no less.