Highlights

- Conservation leasing efforts on state trust lands have been hindered by a lack of economic guidance when comparing competing bids between conservation groups and traditional bidders, such as timber firms.

- Because land under a conservation lease would likely preserve its resource value at the end of the lease, the state would retain the option of generating revenue from the land in the future. Given that conservation leasing preserves an “option value” for the state, a “credit” applied to conservation bids is economically justified.

- Conservation bid credits can be implemented in a variety of ways—upfront during the bidding process or at the end of a lease as a refund—to allow the state to maximize present-value revenue.

- Due to differences in the underlying economics of the natural resources, integrating conservation bids into the leasing process will be easiest in grazing contexts, harder in timber contexts, and hardest in oil and gas contexts.

Key Takeaways

- Revenues from public lands must ultimately derive from the underlying private value of using the land, and auctions are a useful tool for states to capture that private value as revenue via leases.

- The finite nature of leasing substantially complicates pricing through auctions because of the dynamic nature of different use types, such as timber or grazing. Correspondingly, different uses have different implications for the future option value and thus future revenue potential of the land at the end of a lease term.

- Government agencies should apply credit or refund price adjustments to conservation bids to account for the discounted future revenue potential of leased land at the end of the term, due to the option value that conservation leases retain. When employed, these price adjustment strategies would allow for “apples-to-apples” comparisons of upfront bids in an auction between the competing users.

State trust lands make up some 40 million acres of land primarily in nine western states.

Introduction

There is growing recognition that conservation interests ought to be able to compete with extractive interests for use of the tens of millions of acres of leased state and federal lands. Recently, private conservation groups have made several efforts to procure conservation leases from government agencies. In some cases, groups who were willing and able to pay for conservation in competitive auctions were nonetheless stymied by regulatory prohibitions on “non-use” leases, frustrating both conservation interests and those who believe markets are useful allocative tools.1Bryan Leonard et al., “Allow ‘Nonuse Rights’ to Conserve Natural Resources,” Science 373, no. 6558 (2021): 958-61. Even in cases where conservation leasing is allowed in theory, in practice, a number of economic policy choices related to the pricing of such leases need to be addressed by government agencies, including contract duration, royalty structure, and other lease terms. Increasingly, conservation groups are at the table, cash in hand, and government agencies require guidance in how to respond.

The question of conservation lease pricing is particularly relevant for state trust lands, which make up some 40 million acres of land primarily in the nine western states of Arizona, Colorado, Idaho, Montana, New Mexico, Oregon, Utah, Washington, and Wyoming.2Peter W. Culp et al., “State Trust Lands in the West: Fiduciary Duty in a Changing Landscape,” Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, Updated Policy Focus Report (2015): 3-4. State trust lands were initially granted by the U.S. Congress to the states to serve as a source of public revenue, primarily to help fund public education. These lands, which due to the granting process often consist of a checkerboard of scattered sections, are leased to private interests to generate revenue, and states typically have a mandate to maximize the amount of revenue generated from them. Historically, grazing, agriculture, timber, and oil and gas interests have won these leases, with grazing the largest by acreage and oil and gas the largest by revenue. Each state has its own process to allocate leases to private interests, but public auctions with competitive bidding are a common feature to conform with the revenue-maximization mandate that guides state agencies.

For revenue-maximizing state trust land agencies to actually collect revenue, private interests must find it sufficiently worthwhile to pay for the right to graze livestock, cut timber, extract oil and gas, or, in the case of conservation, leave the land intact and unexploited.

The public auctions that allocate state trust lands are often resource specific—agency managers hold auctions for a grazing lease, a timber sale, or the rights to oil and gas extraction on state parcels. This is where the challenge of incorporating conservation leasing into the auction process enters. How should agency managers mandated to maximize revenue consider competing bids for extraction and conservation? For example, if a timber company bids $25,000 for the right to harvest a particular site, while a conservation group bids $10,000 for a 10-year lease that would retain the value of the timber on that site, how should the agency determine the winning bid? This is precisely the challenge that Montana’s Department of Natural Resources and Conservation faced when a conservation group outbid competing timber interests for the Limestone West timber sale in 2019.3Michael Wright, “Saving the Gallatin Front: How Locals Stopped a Timber Sale South of Bozeman With a Law the State Just Repealed,” Bozeman Daily Chronicle, May 12, 2019. Similar issues have arisen in recent years when conservation interests have tried to compete for leases in other contexts.

A Seat at the Table?

In 2020, a conservation organization successfully won an oil and gas lease auction on a 640-acre parcel in Wyoming’s Red Desert.4Birch Malotky, “A New Lease on State Land: How Conservation Is Hoping to Buy a Seat at the Land Management Table,” Western Confluence, March 24, 2022. As a conservation group concerned about wildlife migration and wilderness disruptions, however, they did not intend to develop the lease for extraction. Despite their willingness to pay the bid, the state later canceled the lease due to the group’s lack of intent to develop the parcel. Such “use it or lose it” rules are common across state trust land leases. On the one hand, denying the lease to the largest upfront bidder, even if it happens to be a conservation group, leaves money on the table for the state. On the other hand, a substantial portion of state trust land revenues from oil and gas leases comes from production royalties, which are uncertain at the time bids are made, but are precluded for conservation leases that will result in no production.5Culp et al., State Trust Lands in the West. Yet another factor to consider is that a conservation lease retains an option value for future state revenue, whether through more conservation leases or eventual oil and gas development. The factors that render this an “apples-to-oranges” comparison between different types of bids present an acute challenge for conservation leases.

Similar issues recently emerged for another state trust land parcel in western Wyoming, known as “Parcel 194.” There, an oil and gas company won a lease in 2023 by bidding $19 an acre for a parcel that serves as a critical bottleneck for migrating pronghorn.6Mike Koshmrl, “Wyoming Sides with Industry, OKs ‘Path of the Pronghorn’ Lease As-Is,” WyoFile, October 6, 2023. If conservation interests were able to bid on such a lease to protect the migratory corridor, many likely would have outbid the oil and gas company (although without the possibility of generating production royalties for the state). Several groups lobbied the State Board of Land Commissioners to cancel the lease or impose stricter restrictions on drilling, both of which were ultimately refused. Nonetheless, there could still be potential for conservationists to negotiate with the winning oil and gas company to come to an agreement to reduce habitat and wildlife impacts, while still maintaining the state’s fiduciary responsibility to maximize revenue collection from state trust lands.

This brief aims to provide economic guidance to help answer the various questions regarding pricing conservation leases. In the process, it aims to clarify how state agencies can authorize conservation leases while meeting obligations to maximize revenues. Clarifying agency rules regarding conservation leases, including prices, duration, and related terms, may also help conservation groups determine how to best bid in these contexts. This analysis will be most relevant for the tens of millions of acres of state trust lands that are managed under mandates to maximize revenue, though its insights may also apply to potential conservation leasing at the federal level in the context of lands with more complex, multi-use regulatory objectives. In particular, to the extent that federal agencies were to allow conservation leasing and place weight on revenue generation, the principles regarding pricing strategies developed at the state level below will also be relevant for federal lands.

The analysis below starts from the premise that state trust land managers are trying to allocate leases in a way that maximizes the present-value of revenue—meaning agencies are interested not only in current revenue but also in the flow of revenues over the future, discounted appropriately. In principle, allowing conservation bids alongside traditional extractive bids should increase the revenue that government agencies can collect, because allowing for more types of bidders creates a more competitive bidding process. To understand the potential revenue that can be collected from conservation leases compared to other uses, existing structures for grazing, timber, and oil and gas leases are reviewed. Importantly, different uses have different underlying dynamic economic problems and private values, and these realities inform the structure of the leasing process. Resource-specific pricing strategies are also described, including how conservation leases should be considered when competing with each of the other three resource uses. When employed, these pricing strategies would allow for “apples-to-apples” comparisons of upfront bids in an auction between competing uses. Critically, because conservation leasing retains an “option value” for future leases and revenue for the state—for instance, through future timber harvest, future oil and gas extraction, or renewed conservation leases—a “credit” applied to conservation bids is economically justified.7Traditional-use leaseholders can make various investments that also provide and retain additional value to future leases, and these are often reflected in the lease contract and bidding process. For example, fences put up by ranchers on grazing allotments or forest roads built and maintained by timber harvesters can add value that persists at the end of leases. In that context, conservation is just another type of use, and applying a “credit” to conservation bids is consistent with the treatment of other uses that affect the future value of leased land.

State Land Trust Leasing

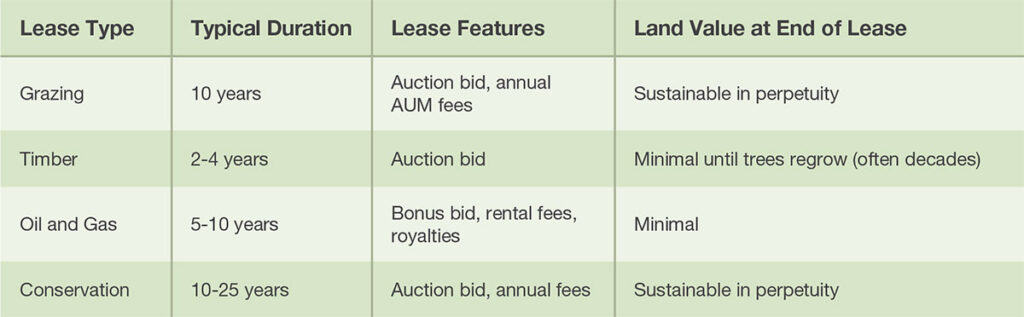

State agencies have developed a variety of methods for collecting revenue from state trust lands. While the methods vary across states, some general features of the leasing process for different resource types are reviewed below. Table 1 provides a summary of the general features of different types of state trust land leases.

Table 1: General Features of State Trust Land Leases

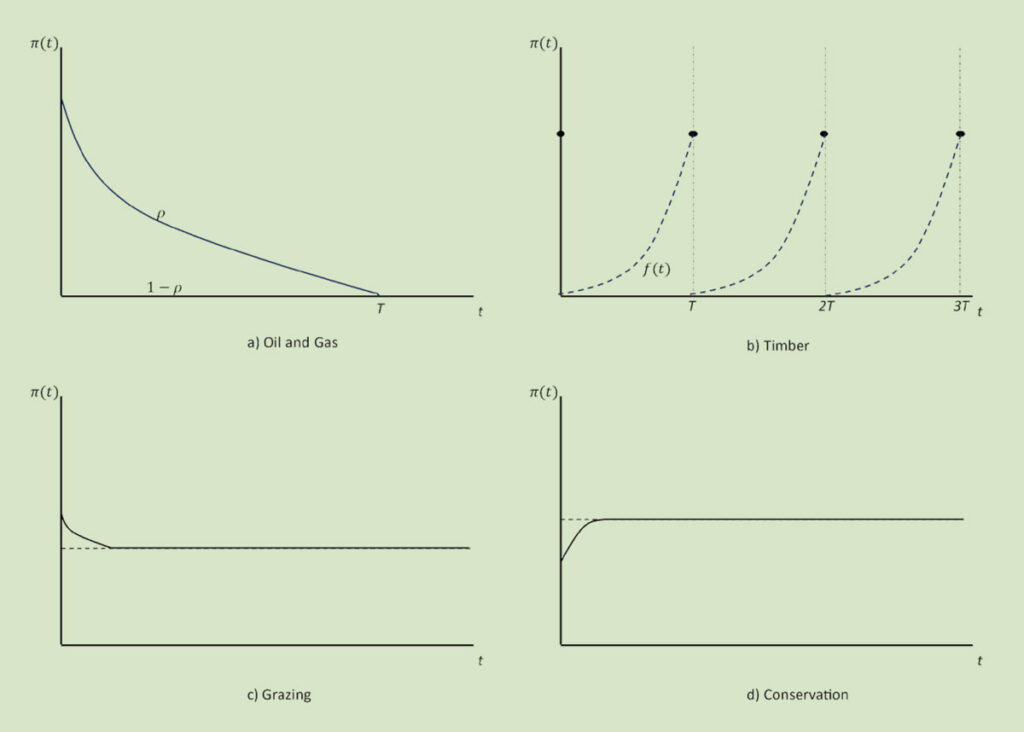

Importantly, for revenue-maximizing state trust land agencies to actually collect revenue, private interests must find it sufficiently worthwhile to pay for the right to graze livestock, cut timber, extract oil and gas, or, in the case of conservation, leave the land intact and unexploited. The details of the private economics of natural resource use are beyond the scope of this brief, but classic dynamic optimization economic models can be found in Conrad and Clark (1987), and numerous other detailed treatments can be found in the academic literature.8Jon M. Conrad and Colin Whitcomb Clark, Natural Resource Economics: Notes and Problems, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987). The core idea is that forward-looking private interests account for the discounted stream of value provided by a certain use—whether it is housing, industry, agriculture, or conservation—and thus determine the value of the property for that use. The dynamic flows of undiscounted private returns from each type of natural resource use examined in this brief are summarized in Figure 1. It is these private returns that agencies tap into via the leasing process to generate revenue.

Figure 1: Hypothetical Private Returns Over Time from Different Resource Uses on a Parcel of Land

Grazing Leases

The grazing lease process on state trust lands typically involves auctions for 10-year leases, with an annual rental payment determined by announced grazing fees per animal unit month (AUM) or via competitive bid. In contrast with uses such as oil and gas or timber, grazing relies on a renewable resource with a relatively fast renewal cycle. The core economic problem is a question of how intensively to use the resource each year—for example, determining the number of cattle to graze based on prices, forage conditions, and other factors.9David Finnoff, Aaron Strong, and John Tschirhart, “A Bioeconomic Model of Cattle Stocking on Rangeland Threatened by Invasive Plants and Nitrogen Deposition,” American Journal of Agricultural Economics 90, no. 4 (2008): 1074-90. Importantly, at the end of a grazing lease, the land retains a great deal of its value and thus can continue to generate future revenue from grazing. Typically, a steady-state level of forage emerges that balances the annual growth of the stock of forage with the annual consumption by grazing animals, generating consistent year-over-year returns for ranchers and lease revenue for state agencies. Existing leaseholders are generally favored in the leasing process, and some grazing leases have remained “in the family” for generations.

Timber Leases

For timber leases, government agencies typically denote specific forest areas for harvest and solicit bids via an auction. The time window for the winning bidder to actually harvest the timber is generally a few years. This lease structure reflects the fact that timber is a renewable resource with a long regrowth cycle. The core economic problem is choosing the length of the harvest rotation—how many years to wait in between successive cuttings.10Waiting longer to harvest will generally yield a higher quantity of timber but has an opportunity cost as waiting pushes profits and revenues further into the discounted future. The classic Faustmann solution is a series of harvest cycles of optimized length that accounts for the growth rate of the forest relative to the discount rate, as well as the opportunity costs of future (discounted) harvests. Note that the annual risk of a forest fire can be added to the discount rate (e.g., increasing it from 5 percent to 7 percent if there is a 2 percent annual probability of fire with total loss). William J. Reed, “The Effects of the Risk of Fire on the Optimal Rotation of a Forest,” Journal of Environmental Economics and Management 11, no. 2 (1984): 180-90. For fast-growing tree species, harvest cycles may be just a dozen years or so, while slower-growing species may have harvest cycles on the order of a century. Lease revenue from timber harvesting is lumpy, with large sums of money at harvest and nothing earned in the long interim years between harvests as the forest regrows. Agencies provide a minimum required bid based on their own estimate of the value of timber selected for a lease, but competitive bidding can push the final bid well above that minimum.

Oil and Gas Leases

Oil and gas leases tend to be more complicated than ones for grazing or timber. State trust land revenues from oil and gas leasing typically include 1) an upfront “bonus bid” via an auction, 2) an annual rental fee, and 3) a potential stream of royalties if production occurs. This structure reflects the underlying private economics of the resource, as firms first determine whether production is economically worthwhile and then determine the optimal production schedule over time to maximize the present value of the finite resource.11Harold Hotelling, “The Economics of Exhaustible Resources,” Journal of Political Economy 39, no. 2 (1931): 137-75; Soren T. Anderson, Ryan Kellogg, and Stephen W. Salant, “Hotelling Under Pressure,” Journal of Political Economy 126, no. 3 (2018): 984-1026. In general, once extraction begins, the quantity of production is initially high before tapering off as a well ages, until the time of exhaustion. (See Figure 1.) Upon exhaustion, the value of the land for further oil and gas use is essentially gone, though lease contracts typically contain environmental remediation requirements to restore the land surface. Through an oil and gas lease, therefore, state agencies receive an amount of certain revenue from the bonus bid and rental fees, along with uncertain but potentially large royalties if revenue is generated by the firm, and then nothing beyond the end of the lease once the resource is exhausted.

Conservation Leases

Finally, there are limited examples of actual conservation leases in place, so it is difficult to describe a “typical” lease. To date, they have tended to have terms of 10 or more years, with conservation bids competing against other uses in auctions. Conservation bids reflect the fact that conservationists derive value from conserving land, though typically not through profit-maximization as with the other types of users. Instead, value accrues to conservation groups via the “non-use” utility value that the land provides, which in many cases depends on the intrinsic, location-specific features of the site, such as its aesthetic qualities or importance as a wildlife corridor or habitat. The non-use value to conservationists may also depend on the ecological condition of the site, which may be improved through mitigation efforts, such as restoring natural vegetation or reducing wildfire risk, during a lease. Similar to grazing, a steady-state condition may emerge, or the land may become even more valuable for future revenue if leaseholding conservationists are able to recover or restore the ecosystem. At the end of any conservation lease, the land is likely to retain the “option value” of being leased again, whether for conservation or other uses, to generate future revenue for the state.

Auctions

In theory, a simple auction awarding the lease to the highest bidder, whether it be a party interested in conservation or extraction, seems intuitive and reasonable. In practice, however, the fact that most state trust lands are managed through leases with finite durations turns out to introduce substantial complications to the simple auction process. In particular, the key feature that conservation leases retain option value for future leases needs to be addressed; otherwise, simply comparing auction bids between conservation and other uses will be comparing “apples to oranges.”

An additional objection is worth noting: concerns over free riders. The traditional environmental economics concern about private auctions is that free-riding incentives will make it difficult for conservation interests to successfully outbid extractive uses. This would lead to too little land being allocated to conservation, relative to a hypothetical social optimum that fully reflected all conservation values in aggregate. However, as noted in Leonard and Regan (2019), for any individual parcel of land, as long as conservation interests are able to outbid the next best use, conservation can win out.12Bryan Leonard and Shawn Regan, “Legal and Institutional Barriers to Establishing Non-Use Rights to Natural Resources,” Natural Resources Journal 59, no. 1 (2019): 135-80. For parcels with particularly high place-based conservation values—for instance, specific recreational amenities, wildlife considerations, or aesthetics—the conservation demand may be very inelastic, while extractive demand may be much more elastic, allowing for high-value conservation parcels to be conserved.

Conservation Leasing and Pricing Considerations

Recall that state trust lands are typically leased for specific uses for a finite period of time.13Or in the case of timber, an auction is held over the right to harvest a certain stand of timber in the next few years. The use of finite-horizon leasing introduces complications such that a simple auction approach of comparing bids is not straightforward. State land trust managers need to consider not only the upfront revenue earned by the current lease under a given use but also the discounted future revenues from subsequent leases.

Consider, for example, a timber sale auction with a logging company bidding to harvest the timber and a conservation group bidding to conserve the forest. If the timber company wins the bid and the land is logged, the state trust receives the revenue from the auction upfront, but the land generates no additional revenue until the forest recovers, potentially decades in the future. By contrast, if the conservation group wins the bid and is awarded a 10-year conservation lease, the land can still generate revenue at the end of the lease term because the trees will still be standing—in effect, the opportunity cost of the conservation lease, in terms of forgone state revenue, is the delayed auction revenues from the timber sale. Therefore, a hypothetical $300,000 bid by a conservation group for a finite-term conservation lease and a $300,000 bid from a logging company are not equivalent in terms of the present value of revenues for the state—the future option value of the land needs to be “priced” into the conservationist bid.

Government agencies could account for the option value that would remain at the end of a conservation lease in one of two ways: an upfront credit during the bidding process or a refund paid out at the end of a lease. Either pricing approach, whether an upfront credit or end-of-lease refund, can achieve the same revenue-maximizing outcome for the state, but there are at least two factors to consider. First, for reasons of appearances, the upfront credit approach may be less desirable because it could result in the agency awarding a lease to a conservation group who nominally lodged a lower upfront bid than a competitor. While there are sound economic reasons for this approach that are consistent with the agency’s revenue-maximizing mandate, an agency could still appear to be unduly putting a thumb on the scale in favor of conservation interests. Second, under the upfront credit approach, the government agency pays at the start of the lease (in the form of accepting a lower upfront bid) and then bears the risk of the conservation group actually preserving the land’s value or executing improvements that will enhance the land’s value by the end of the lease term. By contrast, the refund approach transfers that risk to the conservation group, as it would need to preserve or improve the land to receive the refund.14In theory, nothing would preclude a grazing leaseholder from also receiving a “refund” for improving the land, if the future revenue potential of the land was increased. As noted in Costello and Kaffine, regulatory incentives at the end of finite-term leases can induce efficient stewardship incentives for extractors. Christopher J. Costello and Daniel Kaffine, “Natural Resource Use with Limited-Tenure Property Rights,” Journal of Environmental Economics and Management 55, no. 1 (2008): 20-36. To fund competitive upfront bids, conservation groups could consider using “conservation bonds” or other financial instruments that would pay off at the end of leases upon the receipt of refunds.

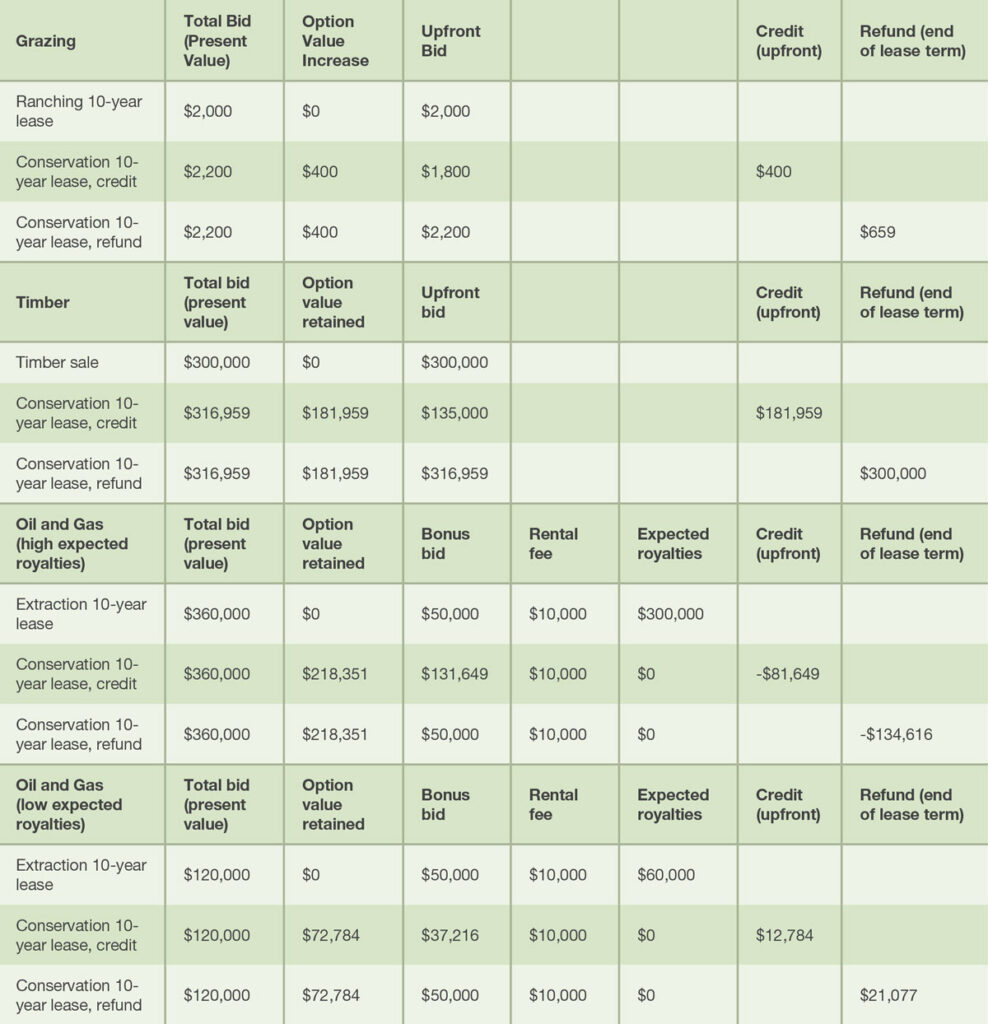

The particulars of pricing will vary with each resource, as discussed further below, but the general principle is that with appropriate adjustments for conservation bids, an auction mechanism can generate apples-to-apples bids for finite-term leases. (See Table 2 for examples.)15Note that while the focus of this discussion is on the auction and bidding process for conservation leases, it is important for government agencies to allow for subleases and “stacking” of uses when appropriate. For example, if a particular section of a parcel with an extractive lease is appealing for conservation (e.g. a migration bottleneck), but less appealing for extraction, subleasing via bargaining between the leaseholder and conservation groups may be a win-win. Ronald Coase, “The Problem of Social Cost,” Journal of Law and Economics 3 (1960): 1-44. Allowing for subleasing can also increase state revenues, to the extent the value of the potential sublease is reflected in higher bids.

Grazing and Conservation Leases

Grazing provides the simplest context for considering conservation pricing, as the dynamics for grazing use and conservation non-use are similar (per Figure 1). In principle, transitioning between a grazing lease and a conservation lease would be relatively straightforward, with the conservation group effectively “buying out” the rancher from their grazing lease.16Shawn Regan, Temple Stoellinger, and Jonathan Wood, “Opening the Range: Reforms to Allow Markets for Voluntary Conservation on Federal Grazing Lands,” Utah Law Review 2023, no. 1 (2023): 4. The only dynamic wrinkle emerges if conservation leases improve the quality of the land at the end of the term, either through natural regeneration or active restoration and mitigation. In that sense, the discounted future revenue value of the land is increased by the conservation lease and should be reflected in pricing.

Two straightforward options are available: First, the government agency could add an upfront “credit” on top of the conservation lease bid, which could then be compared to any grazing bids. If a 10-year conservation lease would raise the discounted future revenue potential by $400 per year (in present value terms), then a conservationist who bid $1,800 per year would win over a rancher who bid $2,000 per year. (Adding the $400 credit to the conservationist’s $1,800 bid yields a total of $2,200 for the conservation lease bid, versus a $2,000 bid for grazing.) Alternatively, the agency could provide a “refund” at the end of a conservation lease equal to the present value of the credit. (In this example, the refund would be about $660 for each year of the lease, paid out at the end of the 10-year term, assuming a 5 percent discount rate.17A refund of $660 in 10 years with a 5 percent discount rate has a present value of $400 because $400*e^(0.05*10)=$660. This same discounting principle could also allow for distribution of smaller annualized refund payments each year (instead of a single large payment at the end of the lease), such that the stream of discounted refund payments equaled the $400 in present value.) Knowing they will likely receive a future refund that is worth $400 per year in present value terms, the conservation group would be willing to bid up to $2,200 upfront, which would beat the grazing bid of $2,000. From a state agency’s perspective, the refund approach may be appealing not only to avoid the appearance of favoring one upfront bid over another, but also because the condition of the land could be assessed at the end of the lease and then refunded appropriately, instead of having to estimate ahead of time how much option value will be retained at the end of the lease term.18There is precedent for such refund approaches for other land-use activities on state trust lands. In New Mexico, agriculture lessees who undertake land stewardship activities receive an annual refund on the grazing rental rate they pay. N.M. Code R. § 19.2.8.20 Range Stewardship Incentive Program. Similarly, Colorado reimburses leaseholders who eradicate noxious weeds. “Eradicating Noxious Weeds,” Colorado State Land Board, accessed February 26, 2024.

Timber and Conservation Leases

As alluded to above, timber sales are a more complex case to consider than grazing, due to the dynamics of timber harvest cycles. Nonetheless, the same basic principles are in place, whereby lease pricing should account for differences in future revenue streams of conservation compared to logging. A key distinction is that while grazing leaves future revenue potential for the land, once timber is cut, there is essentially zero revenue potential from the land for many decades. By contrast, if a forest parcel is under a conservation lease, timber could still be cut once the conservation lease expires, but the delayed revenue collection by the state needs to be accounted for in the price of the lease.

Thus, with timber sales, conservation groups could either receive an upfront credit for the discounted revenue value of a future timber sale or a present-value equivalent refund at the end of the lease, as long as the timber remains standing. For example, assuming a 5 percent discount rate, $300,000 of harvested timber today is worth about $182,000 in present value terms if harvested in 10 years. A conservation group bidding $135,000 and receiving a $182,000 credit today would therefore win against a timber bid of $300,000. (Adding a $182,000 credit to the conservation group’s bid of $135,000 equals $317,000, which is greater than the $300,000 timber bid.)19The $135,000 conservation bid would essentially be like a rental payment for not harvesting the timber on the land for 10 years, and the payment accounts for the opportunity cost of the land. Alternatively, the conservation group could receive a refund for the revenue value of the timber of $300,000 in 10 years at the end of the lease, and would then bid $317,000 upfront, knowing that the refund would likely be received 10 years down the road.

There are two factors to note with conservation lease pricing in the timber context: First, the “appearance” problem of upfront credits becomes extreme in this case—much smaller conservation bids would “win” against larger timber bids, particularly for short-duration leases, even though the underlying economic principles are sound. Second, a non-trivial concern is that a forest may burn down during the conservation lease, and the state would lose out on the timber’s potential future revenue. This risk of fire could either be priced into the discount rate that is used to calculate an upfront credit, or the refund approach could in theory provide incentives for conservation groups to engage in management practices to reduce wildfire risk and protect their “investment.”20Reed, The Effects of the Risk of Fire. Of course, in practice there may be other legal and regulatory complexities related to wildfire risk, which may require additional lease stipulations or terms regarding forest management practices (e.g., mechanical thinning or prescribed burning) that go above and beyond the market incentive provided by the refund. If those stipulations are clear in the terms of the lease contract, bidders will account for them.

Oil and Gas and Conservation Leases

Oil and gas presents the most complex set of concerns when considering conservation leasing. This is due to both option value issues as well as the particulars of how state trust lands typically generate revenue from oil and gas leases. In addition to a competitive upfront “bonus bid” at auction, oil and gas extractors also pay annual rental fees and a known royalty rate from any future extraction revenues. In general, state revenue from royalties is several times larger than the total state revenue from upfront bids and annual rentals.21Culp et al., State Trust Lands in the West. While upfront bonus bids do provide some revenue, perhaps the main benefit to the state of the bonus bid process is ensuring that leases are allocated to firms that expect to be able to profitably produce substantial future quantities of oil and gas and thus future royalty checks. As such, there are two tensions at play when pricing conservation leases in an oil and gas auction. On the one hand, similar to the timber case, a conservation lease preserves the future revenue value of the oil and gas that remains underground at the end of the lease. On the other hand, production does not occur under a conservation lease, meaning the state delays a flow of revenue from extraction royalties. Simply put, an upfront $50,000 bonus bid from a conservation group and a $50,000 bonus bid from an oil and gas company will have very different present-value revenue implications for the state.

Allowing conservation interests to compete for grazing leases may provide a useful starting point that could help agencies learn best practices before addressing the more challenging timber and oil and gas settings.

As such, when evaluating conservation and oil and gas leases, state trust land managers must consider a) an upfront bonus bid, b) an annual rental fee, and c) a potential stream of royalties if production occurs. From the perspective of the state, a conservation lease that paid an upfront bid and an annual rental fee would be forgoing the near-term collection of potential royalties but preserving a future expected revenue stream from later oil and gas extraction.22A key piece of information is the probability that oil and gas can be economically extracted from a particular lease to generate revenue, so the government agency would need some expectation of that probability. The relative size of the expected present value of the near-term royalties compared to the expected present value of the future oil and gas revenues would determine whether conservation bids should get a credit in the bidding process, or, as would likely be the case if significant royalties are expected, conservation bids should actually be penalized.

Why might conservation bids need to be penalized in the upfront bidding process, even though they would preserve the future option value of oil and gas extraction? Suppose that the government agency leasing 10-year oil and gas rights to a large tract of land would collect $50,000 from an upfront bonus bid, receive $10,000 in present value of annual rental fees, and expect royalties of $300,000 in present value terms. The present value of the total revenue to the state would thus be $360,000. A 10-year conservation lease on the same tract of land would hypothetically allow the state the option of generating $360,000 in revenue from an oil and gas lease at the end of the 10 years. The conservation lease, therefore, would retain an option value of about $218,000—the present value of a future oil and gas lease. Leasing to conservationists, however, would also forgo a present value of $300,000 in royalties. For a conservation lease to be revenue-equivalent to the oil and gas bid, the conservation group would have to bid approximately $132,000 in an upfront bonus bid, while also agreeing to pay the $10,000 in present value of annual rental fees. The additional $82,000 added onto the $50,000 bonus bid would cover the opportunity cost of the state delaying for 10 years the $360,000 it would expect to earn in revenue from an oil and gas lease.23The present value to the agency from the conservation lease is $360,000 because the agency would collect the bonus bid of $50,000, the rental fee present value of $10,000, the additional approximately $82,000 payment from the conservation group, and then the revenues from oil and gas development 10 years down the road. In theory, the conservationist need not make the entire payment upfront; for example, it could be paid through higher annual rental fees, as long as the present value of additional payments equals $82,000. There is a possibility that, all else equal, state agencies might prefer a steady stream of certain annual payments from conservation leases to an expected but uncertain equal amount in royalties from oil and gas production. By contrast, if expected present value royalties were only $60,000, then the conservationist bid would receive a credit of $12,784.24It should be clear that the present value of expected royalties plays an important role in determining whether conservation bids should have a credit or a penalty applied to them, which can be challenging to determine in practice. For example, if oil and gas prices were expected to rise over time due to scarcity per a Hotelling-type argument, then the cost of delaying the collection of royalties would be smaller, implying more of a credit for conservation bids. Hotelling, The Economics of Exhaustible Resources. In either case, with price adjustments in place, an upfront auction would yield apples-to-apples comparable bids in terms of state revenue. Note also that if a credit is to be applied, it can be done as either an upfront credit or a refund at the end of the lease, similar to the grazing and timber cases.

Table 2: “Apples-to-Apples” Bids for State Trust Land Leases

Each bid allows for an “apples-to-apples” comparison of the total bid, as each is in terms of present value of revenue collected by the state.

Note: Total bid for grazing is an annual rent; for timber it is a flat fee for timber rights; for oil and gas it is the present value of all aspects of the bid, including bonus bid, annual rental fees, and expected royalties. A discount rate of 5 percent is assumed for all present value calculations. A credit indicates that the amount is credited during the bidding process; a refund indicates that a payment is made at the end of the lease term. A positive credit or refund value indicates that the state pays the leaseholder; a negative value indicates that the leaseholder pays the state. Because grazing and conservation maintain option value for future revenues, the table emphasizes the potential for future revenues from improvements that increase option value. While not reflected here, if extractive users were to make improvements that retained option value and enhanced the ability of the state to collect future revenues, then they should also receive credits/refunds.

Conclusion

This brief attempts to provide guidance for government agencies considering how to price conservation bids for leases on public lands. Several key points emerge, summarized below.

Key Takeaways:

- Revenues from public lands must ultimately derive from the underlying private value of using the land, and auctions are a useful tool for states to capture that private value as revenue via leases.

- The finite nature of leasing substantially complicates pricing through auctions because of the dynamic nature of different use types, such as timber or grazing. Correspondingly, different uses have different implications for the future option value and thus future revenue potential of the land at the end of a lease term.

- Government agencies should apply credit or refund price adjustments to conservation bids to account for the discounted future revenue potential of leased land at the end of the term, due to the option value that conservation leases retain. These credits or refunds could be set to generate equivalent economic incentives and outcomes, and they could be applied either during the initial auction process by crediting conservation bids that preserve the future value of the land or at the end of the lease whereby the conservation bidder is refunded for preserving that future value for the state. When employed, these price adjustment strategies would allow for “apples-to-apples” comparisons of upfront bids in an auction between the competing users.

Two final points deserve note: First, given the different dynamic-use profiles for the different natural resources under consideration, incorporating conservation leasing into grazing contexts is likely easiest, while timber settings would be more difficult, and oil and gas would be hardest. Allowing conservation interests to compete for grazing leases may provide a useful starting point that could help agencies learn best practices before addressing the more challenging timber and oil and gas settings. Second, while this brief focuses on state trust lands due to their clear revenue-maximizing objective, many of the insights that apply to states will also carry over to other regulatory settings, such as management of federal lands by the Bureau of Land Management. In particular, the economic justification for conservation lease credits due to the way they retain option value for future leases has broad application for pricing conservation in general.