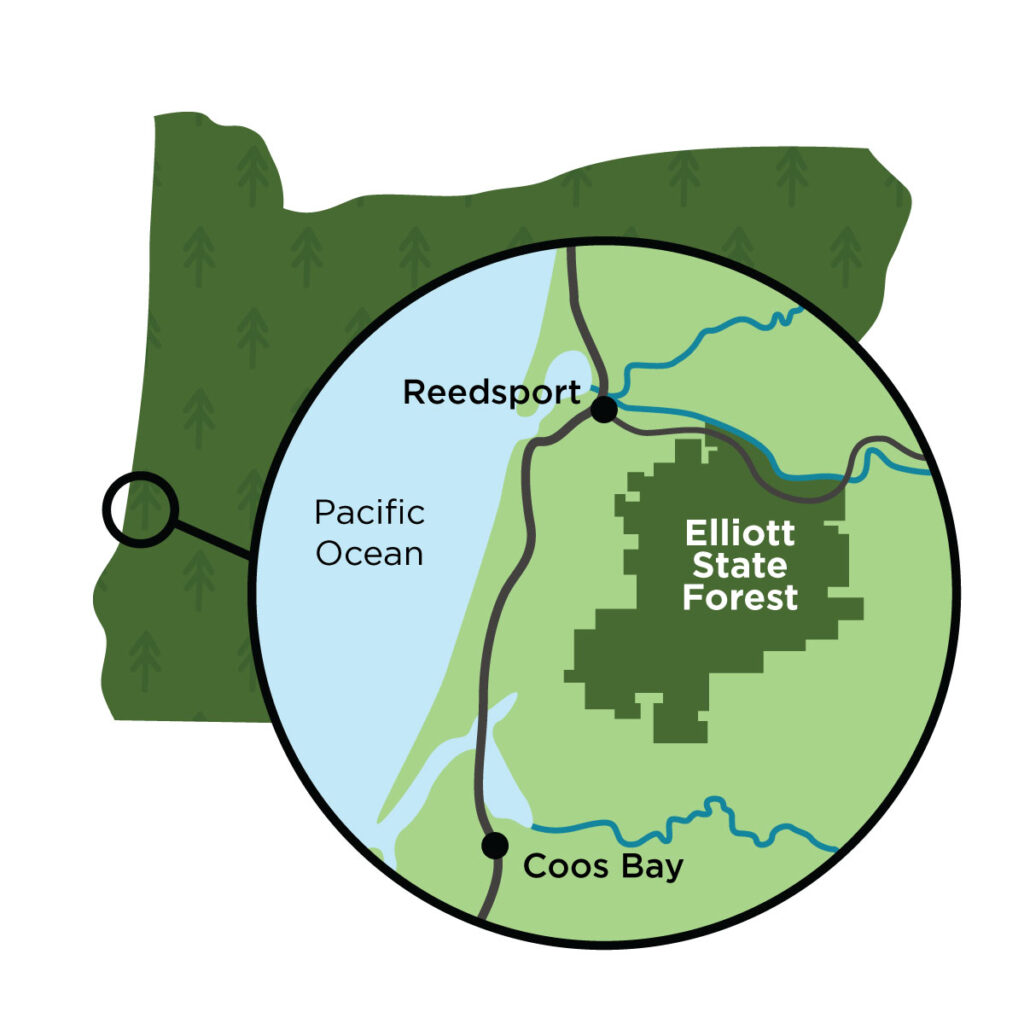

Northeast of Coos Bay lies the 80,000-acre Elliott State Forest, Oregon’s oldest state forest. Because of the area’s steep slopes, it has not been harvested as intensely over the last century as many other forests in the Pacific Northwest. As a result, the forest has a mix of old-growth and second-growth trees that provide habitat for a variety of rare species, including the northern spotted owl and marbled murrelet, a small seabird that nests in forests.

But the forest was not established for environmental reasons. Instead, its existence is due to the federal government granting Oregon lands at statehood to support public schools, as it did for other western states. These parcels—known as state trust lands—came with an important string attached: They must be used exclusively for the benefit of schools, including to generate revenue to cover educational expenses. In 1930, the state consolidated its dispersed state trust parcels through an exchange with the federal government, creating the Elliott State Forest, subject to the same limitation. Over time, the forest generated nearly $300 million to support schools.

Oregon has changed much since the 1930s. Public demand has grown for conservation and outdoor recreation, supporting an ascendant environmental movement. These environmental values repeatedly came into conflict with the state’s duty to manage the Elliott to generate revenue for schools, which it did by selling timber. Environmental groups responded with lobbying campaigns demanding restrictive management plans for the forest and with lawsuits to block logging.

The forest eventually went from an asset supporting public schools to a liability. It generated a $3 million loss in 2013, with the state predicting continued losses into the future. To cover those shortfalls, the state announced plans in 2013 to begin selling off the forest. As one might expect, many environmentalists objected to this also, fearing that the land would be purchased by timber companies and intensively logged. They lobbied against the sale and threatened lawsuits against the state.

The Path Not Taken

It should have been relatively easy to resolve this conflict. The State of Oregon was obligated to do whatever would most benefit public schools. Environmentalists claimed to value the land far more than the timber industry did. And those claims were credible, considering the forest’s unique wildlife and environmental values as well as the resources those groups had put into lobbying and litigation to influence how the forest was managed. So all that was needed was a mechanism for environmentalists to compensate the school trust fund to conserve the land.

Oregon offered that opportunity by putting part of the forest, three parcels totaling nearly 3,000 acres, up for sale to the highest bidder. The state invited bids from anyone, not just timber companies. Its press releases promoting the sale specifically solicited bids from environmentalists, noting that “buyers of all types, including conservation buyers, are encouraged to bid on the properties.” In making that pitch, Oregon was following the lead of other states that had used conservation land sales or leases to resolve similar conflicts over state trust lands.

No such bid would come in. Rather than offering to buy the land, environmental groups chose conflict. They surveyed the land for endangered and threatened species, hoping to identify potential regulatory headaches that might discourage timber companies from bidding. Such efforts were successful. The discovery of threatened marbled murrelets in the forest in 2014 reduced the state’s asking price from $22 million to a mere $3.5 million, a change environmentalists later criticized as a giveaway to industry despite their role in causing the price drop.

Environmental groups also issued public threats against any prospective purchasers. Cascadia Forest Defenders, an activist group, sent a letter to logging companies. “Do not bid on these sales,” they warned. “If you become the owner of the Elliott, you will have activists up your trees and lawsuits on your desk. We will be at your office and in your mills. … We will never stop this fight.” Less confrontational groups merely threatened to sue the state and anyone who purchased the land, hoping to block the sale or any future logging.

Ultimately, the three parcels were sold to timber companies for $4.5 million, money the state used to cover its losses from the remaining land in the Elliott while it worked on a plan for the rest of the forest.

Costly Conflict

Of course, that wasn’t the end of the story. In 2016, a trio of environmental groups—Cascadia Wildlands, Center for Biological Diversity, and Portland Audubon—sued Scott Timber Co., the purchaser of one of the parcels known as the Benson Ridge tract. They alleged that the company’s plan to harvest trees on 50 of the parcel’s 355 acres would harm marbled murrelets and required an Endangered Species Act permit. The groups sought an injunction against logging those acres until the company acquired the permit.

While the case is still pending, the environmental groups have been successful so far. They secured an injunction, which has been upheld on appeal. As a result, the company will have to get a federal permit before logging that part of the parcel. On its face, this seems like a clear win for the environmental cause. But that headline is belied by the details. The decision may be less of a win than it seems, and it was extremely costly.

While it will take substantial time and money, the logging company is almost certain to get a permit. If the federal government refuses to allow any economic use of the land, it would be constitutionally obligated to compensate the landowner for the unregulated value of the land. For that reason, permit requests are almost never denied entirely. Instead, the federal government uses the permit process to extract modest changes to an activity or mitigation for its effects, although this too is subject to constitutional restrictions on how much the agency can ask for.

The probable outcome of the case is that the timber company will, in exchange for a permit, not harvest trees during the marbled murrelet’s nesting season, forgo harvesting part of the land, or improve habitat elsewhere. That outcome would be better for murrelets than unrestricted logging, to be sure, but inferior to the permanent habitat conservation that could have been achieved if environmentalists had purchased the land outright.

Nor did that win come without a cost. In 2022, at the conclusion of the trial phase of the case, the three environmental groups filed a motion reporting nearly $1.2 million in attorney’s fees to that point. The case has since been appealed and, while the groups have not yet reported their costs for that phase of the case, it would not be surprising if the attorney costs have doubled.

This presents a puzzle. The Benson Ridge tract sold for a mere $787,000, or a little more than $2,000 per acre. Given the option to buy and permanently conserve the land at that price, why would anyone spend roughly twelve times as much—$24,000 per acre—on litigation over a part of the parcel that, even if it succeeds, will merely force the landowner to get a permit? From a conservation perspective, this makes no sense. But it is, in fact, an understandable response to the incentives created by federal law, which heavily subsidizes litigation and unintentionally puts a thumb on the scale against other conservation approaches.

Subsidizing Suits

The Endangered Species Act, like several other environmental laws, authorizes “citizen suits” through which virtually anyone can enforce the statute against the federal government, states, or private parties. Providing a right to sue, however, doesn’t mean that anyone will exercise it, especially where doing so is expensive. So when Congress passed the act, it provided that the prevailing party can demand that the losing side pay its costs, including attorney’s fees, a practice known as “fee-shifting.”

Courts can award attorney’s fees under the Endangered Species Act whenever they deem it “appropriate.” In practice, fees are awarded whenever a party “substantially prevails” and achieves some benefit through the litigation. In theory, either side of a lawsuit could seek attorney’s fees under this provision. But the vast majority of fee awards are to plaintiffs, and courts have adopted heightened standards for defendants seeking fees.

At first blush, it might seem like this arrangement shouldn’t encourage litigation that much. Groups seemingly still bear the costs of cases that they lose and are merely made whole for those that they win. But that’s not how it works in practice. The amount of fees awarded is almost always far more than necessary to reimburse a prevailing plaintiff. When courts award fees, they do not look at the actual amounts paid to the attorneys in the case. Instead, they set a hypothetical hourly rate for each attorney and then multiply that rate by the number of hours each attorney reported working on the case. In theory, this method could equate to the actual costs to litigate the case, if the hourly rate selected by the court matches the rate the attorney actually charged. But that will rarely happen in practice. Instead, court-set fees usually exceed the rate the party would pay if they lost the case.

The environmental groups that brought the Benson Ridge case, for instance, assert hourly rates ranging from $140 an hour (for the work of a law student intern) to $650 an hour (for an attorney with 30 years of experience). An experienced attorney at a nonprofit organization will often make somewhere between $100,000 and $200,000, which equates to an hourly cost to the organization of $50 to $100. Assuming the court accepts the rates asserted, as most do, the work of a law student intern will be compensated at a rate higher than virtually all senior nonprofit environmental attorneys are actually paid.

Some of the attorneys involved in the Benson Ridge case are employed by their organizations, rather than working for outside firms. Public financial forms show that one of the attorneys involved in the case makes less than $125,000. This translates to an hourly rate of less than $62.50. The rate for that attorney asserted in the Benson Ridge case, however, is $515 an hour, which represents at least a 700 percent profit margin for the organization whenever it can recover for the employee’s time in an attorney’s fee award.

None of this is meant to criticize the particular organizations and attorneys involved in that case. They are simply responding to the incentives that policy creates. The point, instead, is that the way attorney’s fees are calculated, they often do not simply make litigious groups whole but lavishly reward them for bringing Endangered Species Act cases.

Whatever the (Opportunity) Cost

With that background, it’s easier to see why a group would choose to litigate over the Elliott State Forest rather than to purchase it and permanently conserve the habitat. If the groups had bid and won the parcel, they would have secured a huge conservation win but would have been on the hook for the purchase price. If the conservation value of the parcel far exceeded the purchase price, a group would presumably pursue that option. But if the conservation value and the purchase price are reasonably close, such that the group is almost indifferent between purchasing the property or not, it might look for other options to pursue its goals.

While litigation initially seems like a poor alternative, considering the reduced conservation benefit and high costs, the prospect of attorneys’ fees can change this calculus substantially. Litigation could result in the worst possible outcome—spending several hundred thousand dollars for no conservation benefit. But it could also offer the best outcome. If the case succeeds, the group can secure a conservation benefit, albeit a more modest benefit than could be achieved from purchasing the land, while also generating a windfall.

Under current policy, the choice faced by the environmental groups in the Elliott State Forest case was not in fact to spend $787,000 to permanently conserve 355 acres of habitat or spend $1.2 million litigating over a permit. Instead, the litigation calculus was something closer to purchase the land or litigate and lose $150,000 if the case fails or make more than $1 million on net if it succeeds.

In such a circumstance, a group should choose litigation even if the odds of success are only 50/50, so long as the difference in value of the conservation outcome between the two options is less than $450,000. If the odds of success are greater, the group will favor litigation even if the difference between the conservation value it can achieve and what could be achieved through other strategies is far greater.

The Endangered Species Act has famously been described as demanding species protection “whatever the cost.” We might think of the law’s attorneys’ fees provision as favoring litigation whatever the opportunity cost. Under it, little or no consideration is given to the extent to which a lawsuit produces real-world benefit or the alternative ways a group could have achieved the same or more conservation benefit. The result is a heavy thumb on the scale in favor of litigation—so heavy that it can induce groups to favor litigation even in the face of a cost-effective way to secure a bigger conservation win by other means.

In the end, the scales are tipped in favor of conflict, not necessarily what’s best for species conservation. If we truly care about conserving places like the Elliott State Forest, it’s time to ask: Should we be subsidizing litigation this heavily, especially at the expense of more direct and cost-effective conservation approaches?