This project is a collaboration between PERC and Ducks Unlimited.

Introduction

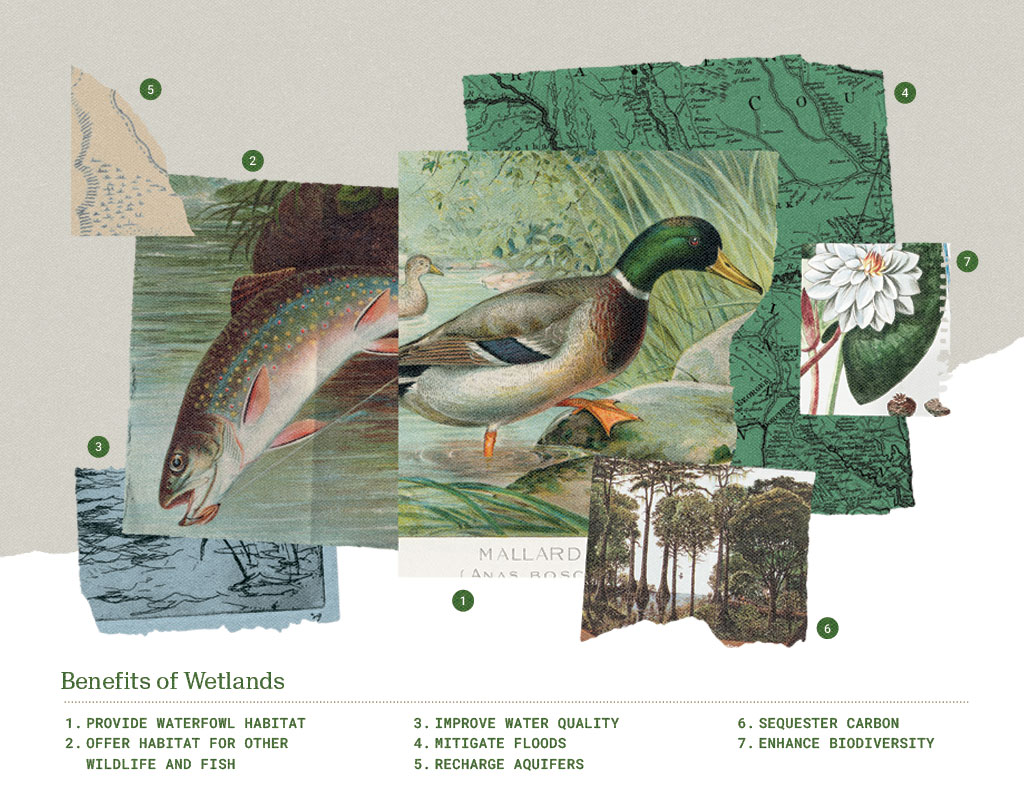

Wetlands provide numerous essential services, including wildlife habitat, flood mitigation, water filtration, aquifer recharge, and carbon storage. The Supreme Court’s 2023 Sackett v. EPA decision limited federal jurisdiction of wetlands under the Clean Water Act and reshaped the regulatory landscape for wetland protection in the United States. However, it did not diminish the ecological, social, or economic importance of these areas.

About three-quarters of U.S. wetlands are owned by private landowners, making them the preeminent stewards of wetlands. The post-Sackett legal shift has prompted critical conversations about how to move beyond federal regulation to conserve wetlands through state and local action, and incentivize and scale conservation efforts with private landowners at the forefront.

To explore conservation solutions that align with this new legal environment, the Property and Environment Research Center (PERC) and Ducks Unlimited (DU) co-sponsored a workshop in March 2025, hosted at Ducks Unlimited headquarters in Memphis, Tennessee. The event brought together a diverse group of conservationists, policy leaders, scientists, and state and local officials to identify opportunities for voluntary, market-based, and state- and local-level wetland conservation.

About three-quarters of U.S. wetlands are owned by private landowners, making them the preeminent stewards of wetlands.

The workshop focused on innovative strategies for the future, absent broad federal protections. Participants identified creative tools, approaches, and policies for wetland restoration and stewardship, especially on private lands. Discussions covered state-level responses to Sackett, market-based incentives, mitigation banking, habitat protection, water-quality trading, flood resilience, innovations in data and mapping, and other pressing topics.

PERC and Ducks Unlimited thank all attendees for contributing their expertise and insights, which have shaped this report. The report outlines key themes that emerged from the workshop and identifies promising opportunities to enhance and expand wetland conservation, including innovative landowner engagement, state- and local-level initiatives, novel financing strategies, and potential pilots to model a more sustainable future for wetland stewardship.

Background

Wetlands offer tremendous ecological and social value, including improving water quality, enhancing wildlife habitat, supporting biodiversity, mitigating floods, and recharging aquifers. However, agencies, industry, and private landowners have long been subject to legal and political uncertainty and tension regarding the scope of wetland protection under the Clean Water Act. The 2023 Sackett v. EPA decision redefined which wetlands are federally regulated, creating new legal uncertainties and removing coverage from many features previously under federal authority.

Striving to overcome the decades of uncertainty under the Clean Water Act, PERC and Ducks Unlimited recognize that practical solutions customized to meet landowners at the state and local level may be the best way to assure wetlands persist across the many ecosystems of the United States. Standing on the firm foundation that nearly 90 years of voluntary habitat conservation has produced for wetlands, the workshop explored ideas to work with and not against, landowners, the types of state regulatory regimes that may fill the federal void, and what tools—financial, legal, or institutional—can be harnessed to promote conservation.

Workshop

The workshop spanned three days and featured a combination of plenary sessions, roundtable discussions, and networking events. Each substantive session focused on a specific topic:

- Environmental Federalism and Wetland Conservation: Explored how states with varying political landscapes are navigating wetland policy in a post-Sackett context

- Habitat Conservation: Focused on leveraging wildlife conservation to encourage wetland restoration

- Flood Control and Coastal Resiliency: Examined how wetlands can reduce flood risk, increase coastal resiliency, and buffer against the impacts of shifting climates

- Water Quality and Quantity: Looked at market-based tools such as trading, lease programs, and aquifer recharge initiatives that can drive conservation

- Innovations in Conservation: Highlighted new mapping technologies, mitigation banking improvements, and other creative approaches to conserve wetlands

Key Themes

Several key themes emerged over the course of the event:

1. Market-Based Mechanisms and Innovative Incentives

A recurring message was that financial and market-based incentives can support wetland conservation. Several examples were highlighted by participants.

- Ducks Unlimited highlighted a restoration project near St. Louis, Missouri, that provided several benefits from the restoration of 1,800 acres of wildlife habitat for flood mitigation. True to DU’s conservation approach, several conservation partners contributed to completing the project and leveraged federal and non-federal grants.

- In Northwest Florida, the water management district used fee simple acquisition to secure nine flood-prone parcels for wetland and springs conservation, funded by a state program that aims to protect freshwater springs. Offers generally begin at 90 percent of appraised value and increase to 100 percent, illustrating a flexible and cost-effective strategy for public flood mitigation.

- In Iowa, county-level programs coordinated landowners to restore wetlands that feed into the Des Moines River. Co-ops expedited planning and implementation far faster than federal funding channels would have allowed.

2. Pilots and Partnerships for Scalable Impact

Several promising ideas emerged for demonstrating success through on-the-ground pilot efforts:

- While federal protections for wetlands have diminished, the demand for upgraded and new infrastructure is stronger than ever. Development continues to impact wetlands and DU is playing a key role in assuring wetland losses are offset via compensatory mitigation. As states work to fill the regulatory void, Ducks Unlimited is building projects that replace non-regulatory wetland losses through either state regulations in Colorado, New York, and others or address current no-net-loss wetland policies carried on for decades by federal agencies. Ducks Unlimited has played a key role in facilitating mitigation transactions, ensuring that restoration projects align with both regulatory requirements and ecological priorities. By leveraging its expertise in wetland conservation and mitigation banking, DU has helped create a model that supports private-sector investment in landscape-scale habitat restoration.

- A Tennessee example demonstrated how two public park sites near Jackson, with private lands in between, could become a restoration corridor by partnering with local landowners. Rather than viewing the private parcels as barriers to connectivity, the idea was to engage willing landowners to participate in voluntary restoration projects. The example illustrates a broader strategy of integrating wetland conservation into local planning and development efforts, demonstrating how small-scale, place-based collaboration can yield landscape-level benefits, particularly in regions where comprehensive public or large-scale conservation may not be feasible.

- In Norfolk, Virginia, the Elizabeth River Project implemented a rolling easement that will allow wetlands to reclaim territory as sea levels rise and water migrates inland. The group purposely built a research center in a low-lying zone but agreed to remove structures and relocate the facility to higher ground once the average tide level rises enough to trigger the easement, estimated to occur around 2085. The example offers a novel model for blending financial viability with climate resilience, particularly in developed coastal zones.

3. Strategic Communication and Community Engagement

Participants noted that effective conservation requires new narratives and messengers.

- Communication should move beyond scientific jargon to storytelling that resonates with farmers, hunters, insurers, brewers, and local communities. For instance, flood mitigation and aquifer recharge directly address the concerns of downstream homeowners and water utilities.

- The BirdReturns project, led by The Nature Conservancy in California, has used reverse auctions to compensate farmers for flooding fields during bird migrations. This approach leverages market principles, meets conservation goals, and has generated strong public relations value. It also demonstrates a mutually beneficial arrangement between agricultural producers and conservationists that merits more research into whether such a model could be adapted and scaled elsewhere.

- In parts of the Intermountain West, channelized streams and nutrient loss have harmed water quality and fish populations. Recognizing flood irrigation as a water-quality-enhancing practice, rather than an inefficiency, can transform a perceived liability into a valued approach to help sustain wetlands and support wildlife. Moreover, attendees noted that where flood irrigation is practiced, efficiency can often be improved significantly up to the point where water reaches the field, conserving a large amount of water in the process. Local context and practices, however, will dictate the trade-offs of such practices—including the amount and type of pollution runoff that flood irrigation adds to streams—and must be weighed accordingly.

4. Addressing Policy and Program Barriers

The complexity of existing public conservation programs can deter landowners from participating in these programs. Recommendations included the following:

- Participants proposed a common application for the “alphabet soup” of federal programs that offer incentives for wetland conservation. Potentially overseen by the Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ), such a clearinghouse would mean a landowner has to fill out only one application to be considered for a variety of federal programs, without even having to know that they exist.

- Colorado’s easement tax credit program and Oregon’s aquifer recharge partnerships exemplify successful financial incentives that could be more widely adopted.

- EDF and Stetson University were recognized for their work on predictive wetland mapping using satellite imagery and LiDAR. These tools can help identify high-potential restoration areas and reduce planning friction.

5. Environmental Federalism and State Leadership

Participants emphasized the importance of state-level innovation. With federal regulation diminished, wetland conservation need not be dominated by national politics. States have a unique opportunity to re-enter the arena and develop wetland programs tailored to local conditions. Specifically, participants from Colorado and Tennessee—home of DU and the site of the workshop—helped shed light on their proactive and customized approaches to wetlands regulation.

Colorado

Colorado’s response to the Sackett decision has been notably proactive and collaborative, reflecting both its unique political makeup and ecological needs. While Democrats currently hold power at the state level, Colorado remains a politically “purple” state with strong agricultural and industrial sectors that influence policy direction. Recognizing the significant implications of the ruling, Colorado leaders opted not to merely “fill the gap” left by the decision. Instead, they chose to design a comprehensive and independent regulatory framework tailored to the state’s hydrological realities.

Even before Sackett was finalized, Colorado had convened a diverse task force comprising agricultural, construction, development, and conservation interests, as well as sportsmen’s groups. The task force’s work led to bipartisan legislative efforts, which initially resulted in two distinctly different bills. Through negotiation and compromise, these were eventually merged into a single piece of legislation that aimed to regulate state waters broadly, encompassing wetlands and streams that no longer fall under federal authority. The statute includes detailed exclusions and exemptions for certain activities in response to stakeholder input and establishes a framework for general permits. One such permit covers voluntary ecological enhancement projects, a provision that Ducks Unlimited helped forge.

With the legislation now passed, the focus has shifted to implementation. State agencies are developing detailed rules and regulations, with a significant emphasis on compensatory mitigation. This is particularly urgent given that in Colorado, an arid state, 50 percent of stream miles and 60 percent of wetlands—many of which are intermittent or ephemeral—are now principally under the authority of the state.

Tennessee

Tennessee’s approach to wetland regulation following the Sackett decision has been shaped by its deep-red political landscape and a Republican supermajority in the state legislature. Unlike some states that saw Sackett as an opportunity to expand state-level protections, Tennessee’s initial response leaned toward deregulation. Early efforts included proposals to align state wetland protections with the narrowed federal standards, essentially rolling back the state’s authority. One proposal to significantly limit state jurisdiction over wetlands was ultimately paused and sent to a legislative “summer study”, a move often used to sideline bills. In this case, it became a meaningful avenue for further deliberation.

The summer study yielded several principal recommendations. For one, it called for clarifying state jurisdiction in light of Sackett and creating a state-wide wetlands conservation strategy, including improvements in permitting efficiency and transparency. It also highlighted the need for increased, sustained, and diversified financial support for wetland conservation, calling for dedicated state funding sources such as conservation trust funds or user fees, expanding access to cost-share and technical assistance programs for landowners, and supporting market-based conservation tools like mitigation banking and payments for ecosystem services. It also suggested promoting wetland protection through land-use planning and development tools, such as density bonuses or credits.

States have a unique opportunity to re-enter the arena and develop wetland programs tailored to local conditions.

Moreover, there was significant concern about how to address cumulative impacts from development, particularly in the absence of adequate data to model or predict long-term consequences. Lawmakers and stakeholders debated whether mitigation should be required upfront or could be phased in, acknowledging that the lack of data made it challenging to craft precise rules. The question of how many acres, particularly of low- or medium-quality wetlands, should be exempt from mitigation requirements generated considerable discussion.

Ultimately, Tennessee passed legislation in 2025 that largely reduced wetland regulation, including by eliminating mitigation requirements for most of the state’s isolated wetlands. Yet despite the state’s overall political leanings, Tennessee’s response to Sackett has not solely been about deregulation; state policymakers have recognized the need for better tools and planning to balance wetland conservation with economic development. While it may take years to fully understand the impact of the policy shifts, Tennessee’s trajectory suggests a deliberate effort to refine its wetland management approach in light of reduced federal regulation.

Opportunities

The Sackett ruling dramatically reshaped wetlands protection, but it also provided space for novel leadership, creative policy experimentation, and pragmatic conservation. Rather than relying on the old playbook, this moment presents an opportunity to rethink how wetlands are valued, conserved, and integrated into broader land and water management frameworks. The ideas below reflect promising areas of focus and innovation.

1. Grassroots Engagement at the State and Local Levels

In light of continued disputes over the federal government’s jurisdiction over wetlands and Congress’s unlikeliness to expand the jurisdiction of the Clean Water Act, conservation organizations must elevate efforts to work with state and local governments. Opportunities exist to expand direct work on wetlands conservation at the State and local levels, increase engagement with landowners, educate the public, and promote wetlands as solutions to our most pressing environmental crises. Conservation groups need to step up as policy advocates and as active partners in implementation. The new legal reality presents an opportunity to re-engage stakeholders on wetlands conservation as a collaborative, landowner-centered effort. What would a long-term sustained wetland education campaign look like, and how could it influence public perceptions and actions?

2. Promote Market-Based Wetland Conservation Policies and Incentives

Wetlands are widely considered one of the most valuable environmental assets on Earth because of their disproportionately high level of benefits, and yet over half of them have been lost to agriculture, urban development, and other human activities. Conservation and restoration of wetlands across the United States can be achieved through policies that leverage the power of federalism by setting scientifically supported baselines for water quality, flood resilience, biodiversity, and climate adaptation that leaves to each state the flexibility to meet or exceed baselines according to their needs. Such adaptability is crucial partly because the value of an acre of wetlands in one place may be wildly different from the value of an acre in a neighboring county or in another state, let alone an acre of wetlands on the other side of the country. States should be encouraged to move toward policies that promote incentives and market-based solutions to achieve their goals, and wetlands can play a significant role. States can serve as laboratories as they craft wetlands laws and policies tailored to their specific conditions, design independent wetlands programs, leverage local expertise, address diverse hydrological realities, and capitalize on state and local leadership.

3. Innovative New Models to Pay for Wetlands Conservation

A recurring theme in our workshop discussions boiled down to: Who pays for wetlands conservation? There is a clear need to test new models that harness demand for wetlands and the multiple benefits they provide. One potential area is wetland credit markets targeted at non-developer, conservation-focused buyers, and relying on bundles of quantifiable wetland benefits. Another idea could harness development interests to maintain or restore wetlands, whereby states incentivize developers who avoid or mitigate planned impacts with streamlined permitting and planning processes or leeway to build more or more intensively in less-sensitive areas. Other opportunities involve creative approaches to leverage existing policies to capture individual benefits that wetlands can provide. For instance, a small-scale experiment with the national flood insurance program could offer more appealing buyouts for repeat-loss properties, building on existing FEMA mitigation grants but explicitly linking them to individual policyholders and wetland restoration benefits.

4. Cut Green Tape

Landowners and conservation partners often face a bewildering array of federal and state wetland programs, each with its own rules, acronyms, and paperwork. The complexity of this “alphabet soup” discourages participation and slows restoration. There is a clear opportunity to streamline access to existing programs by developing a unified application process, creating a centralized clearinghouse for landowners, and simplifying eligibility criteria across agencies. Making restoration more user-friendly and easier to navigate could dramatically increase participation, especially among private landowners who are willing but unsure about how to proceed. Relatedly, novel ideas to streamline permitting processes, for instance, by licensing qualified entities who carry out projects rather than regulating activities based on forecasting, have the potential to expand and improve conservation efforts.

5. Broaden the Coalition

Wetlands conservation often operates within a narrow policy and stakeholder lane. Expanding the tent to include a broader range of interests—such as insurers, brewers, developers, floodplain managers, and agriculture groups—could open new pathways for funding, innovation, and public support. These groups already benefit from the ecosystem services that wetlands provide, including flood control, water purification, aquifer recharge, and recreational opportunities. Educating stakeholders on the value of wetlands as beneficial green infrastructure—rather than as regulatory red tape—can shift perceptions and attract unlikely but powerful allies.

6. Launch Pilot Projects

Demonstration projects can prove concepts and build momentum. Wetlands pilot initiatives in high-impact regions, such as the Mississippi River Basin, flood-prone coastal areas, or arid landscapes with groundwater recharge needs, can serve as proof points for future scaling. These projects could test innovative finance models, restoration techniques, or incentive structures in real-world settings. By choosing areas where multiple benefits overlap—such as habitat, water quality, flood mitigation, and agricultural resilience—pilots can demonstrate both ecological and economic benefits, thereby building broader public and political support.

Potential Next Steps

Building on the ideas generated during the workshop, several actionable next steps can help translate key themes into concrete outcomes. The following initiatives aim to explore promising opportunities for wetlands conservation.

- Develop a series of case studies and pilot proposals based on workshop input. Identify a diverse set of regions and wetland types—such as flood-prone coastal communities, arid stream systems, and working lands in agricultural basins—to serve as real-world testing grounds for pilot projects. These case studies should demonstrate innovations in market-based tools, landowner engagement, and cross-sector partnerships, and offer models for replication and scaling.

- Consult stakeholders to refine a common application or “green tape” reduction strategy. Develop a framework for a simplified, centralized application model. Engage key partners, including federal and state agencies, landowner groups, and conservation groups, to explore feasibility, align priorities, and build consensus for streamlining access to existing incentive programs.

- Host a follow-up convening to assess progress and foster continued collaboration. Consider organizing a virtual or in-person follow-up event to check in on pilot efforts, share progress on implementation, and keep the network of engaged stakeholders active and engaged. This could include updates from case study regions, new funding opportunities, and breakout sessions to tackle emerging challenges or promising new ideas.

- Create a clearinghouse or resource hub for wetlands conservation tools. Build a publicly accessible online resource that aggregates tools, model policies, example permitting frameworks, and success stories, especially ones that emphasize voluntary, incentive-based, and multi-benefit conservation approaches. This could serve as both an educational tool and a practical guide for practitioners and policymakers.

- Publish a “Wetlands Innovation Briefing Book” for state policymakers. Synthesize workshop findings and related follow-up work into a practical, easy-to-navigate briefing tailored for state legislators, agency staff, and local governments. Focus on actionable models for state-level leadership post-Sackett, and highlight options that reflect regional realities.

- Engage and expand the coalition of non-traditional partners. Identify and approach stakeholders who benefit from wetlands, such as flood insurers, brewers, developers, and utilities, to explore partnership and investment opportunities—conservation is not only an environmental good, but also a cost-saving, resilience-building strategy.

Conclusion

This workshop reinforced the idea that wetland conservation must evolve alongside the changing legal and regulatory landscape and laid a foundation for future efforts. The Sackett decision changed the regulatory landscape and created new opportunities for innovation, leadership, and renewed energy at state and local levels.

There is fertile ground for future efforts focused on market tools that align landowner incentives with public benefits, provide short- and medium-term conservation agreements that offer flexibility, and bundle multiple wetland benefits into more compelling projects. Equally important are new advances in mapping and permitting and the opportunity to build a broader, more diverse coalition, including partners who don’t traditionally see themselves as stakeholders in wetlands. Lastly, there is clearly a great deal of space for state and local policy entrepreneurship that reflects the realities of federalism to meet the natural resource and water needs of individual states.

The Sackett decision changed the regulatory landscape and created new opportunities for innovation, leadership, and renewed energy at state and local levels.

PERC and Ducks Unlimited aim to harness the lessons from this event to inform future research, pilot projects, outreach strategies, and cross-sector partnerships that prioritize, improve, and expand wetland conservation across the country. We hope this workshop helps mark the beginning of a more decentralized, pragmatic, and creative chapter in America’s wetlands story—one built on collaboration, adaptability, and shared benefits.

This project is a collaboration between PERC and Ducks Unlimited.

Ducks Unlimited (DU) is the world’s leader in wetlands and waterfowl conservation. DU got its start in 1937 during the Dust Bowl when North America’s drought-plagued waterfowl populations had plunged to unprecedented lows. Determined not to sit idly by as the continent’s waterfowl dwindled beyond recovery, a small group of sportsmen joined together to form an organization that became known as Ducks Unlimited. Its mission: habitat conservation. Thanks to decades of abiding by that single mission, DU is now the world’s largest and most effective private waterfowl and wetlands conservation organization. DU is able to multilaterally deliver its work through a series of partnerships with private individuals, landowners, agencies, scientific communities, and other entities.

The Property and Environment Research Center (PERC) is the national leader in market solutions for conservation, with over 40 years of research and a network of respected scholars and practitioners. Through research, law and policy, and innovative applied conservation programs, PERC explores how aligning incentives for environmental stewardship produces sustainable outcomes for land, water, and wildlife. Founded in 1980, PERC is nonprofit, nonpartisan, and proudly based in Bozeman, Montana.