One Wednesday in July, a water pump failure at Grand Canyon National Park put the Transcanyon Pipeline out of commission yet again, leaving the South Rim of the canyon without a reliable source of potable water. Park officials were forced to implement conservation measures, asking visitors to purify their own water and scale back toilet flushing. This wasn’t a first. The pipeline, which supplies water to more than 6 million annual visitors and 2,500 year-round residents, breaks five to 30 times each year.

It’s hard to imagine these steps don’t significantly affect the experience of park visitors—public bathrooms can be rough even when toilets flush at peak capacity—but park staff had little choice. The measures were the consequence of a water system that has exceeded its useful life and should have been replaced years ago. In that sense, the pipeline is emblematic of public land infrastructure across the country: timeworn, overused, and in desperate need of repair.

It’s no secret that U.S. public lands are riddled with maintenance needs. Wear-and-tear has outpaced budgets for decades. By the latest count, nearly $20 billion of deferred maintenance projects have accumulated across all federal land agencies, with more than $12 billion in the National Park System alone. This immense need is spread across thousands of miles of dilapidated roads, countless washed-out trails, numerous outdated water and sewage systems, and a multitude of run-down structures and campgrounds. Grand Canyon needs roughly $100 million just to replace the leaky Transcanyon Pipeline.

What made the latest pipeline failure at the Grand Canyon notable is the day it happened. As the South Rim went without water, Capitol Hill buzzed with news that overdue maintenance on public lands might finally be addressed—the Great American Outdoors Act had just passed in Congress and would soon be headed to the president’s desk. A few days later, with the bill signed into law, legislators celebrated the act’s intent and scope. Senator Steve Daines, a co-sponsor, called it “the greatest achievement in 50 years for conservation.” President Donald Trump redoubled the praise, describing it as “the most significant investment in our parks since the administration of the legendary conservationist President Theodore Roosevelt.”

Perhaps they’re right. The Great American Outdoors Act will devote significant resources to public lands, first by mandating full annual funding of $900 million for the Land and Water Conservation Fund, which funds most federal land acquisition and provides grants to states for outdoor recreation purposes. The act also creates the National Parks and Public Land Legacy Restoration Fund, a program to address deferred maintenance on public lands that’s authorized to receive up to $9.5 billion over the next five years. But over the long run, the legislation seems to get the conservation-funding issue backward: It mandates perpetual funding for land acquisition through the LWCF but provides only temporary funding for maintenance on public lands. More acquisition will eventually mean a larger federal estate, and the act provides no way to pay for the upkeep of it—all at a time when it’s clear that federal agencies cannot properly maintain their existing assets.

While the Great American Outdoors Act will provide much-needed dedicated funding for public lands, solving several foundational issues is the only way to assure a solid future for conservation and recreation on federal lands.

Moreover, the act does not address the fundamental issue that spawned the maintenance backlog: a neglect of routine maintenance. When infrastructure and assets are not serviced on time as part of today’s routine maintenance, they become tomorrow’s deferred maintenance, ultimately costing federal agencies, public land users, and taxpayers even more. If routine maintenance continues to go undone, deferred maintenance will continue to accrue, even as the restoration fund addresses the current list of overdue projects.

The act also relies on a potentially uncertain and fraught funding source. Both the LWCF and the restoration fund are entirely funded by revenues from energy development on federal lands and waters, which predominantly come from oil and gas. But several factors threaten the viability of relying on these revenues for conservation and recreation programs.

In a series of new policy briefs published by PERC, we explore these issues in detail and make several recommendations for how to improve federal land management. These reports, which we summarize here, demonstrate that while the Great American Outdoors Act will provide much-needed dedicated funding for public lands, solving several foundational issues is the only way to assure a solid future for conservation and recreation on federal lands.

Issue #1: Addressing overdue maintenance is vital, but the root of the problem is a lack of attention to routine maintenance

The National Parks and Public Land Legacy Restoration Fund will certainly help address deferred maintenance, but public lands need sound fiscal strategies for routine maintenance so that they avoid ending up saddled with another backlog in the future.

Take national parks, for example. For years, funding for parks has not been sufficient to keep up with the maintenance needs of aging assets and infrastructure. Part of the neglect can be chalked up to the fact that the majority of park funding comes from congressional appropriations, an inherently political process. “It’s fun and sexy to add a new unit to the Park Service,” Utah Representative Rob Bishop has said in acknowledging the issue. “It’s not fun or sexy to talk about fixing a sewer system.” Over time, agency budgets have continuously stretched thinner as the number of new parks and assets has grown, and the maintenance problem has compounded. As a result, many public land users encounter eroded trails, dilapidated campgrounds, pot-holed roads, and leaky water systems.

Making a dent in the deferred maintenance backlog would be great progress, but if routine maintenance remains neglected, the fundamental problem will remain unresolved.

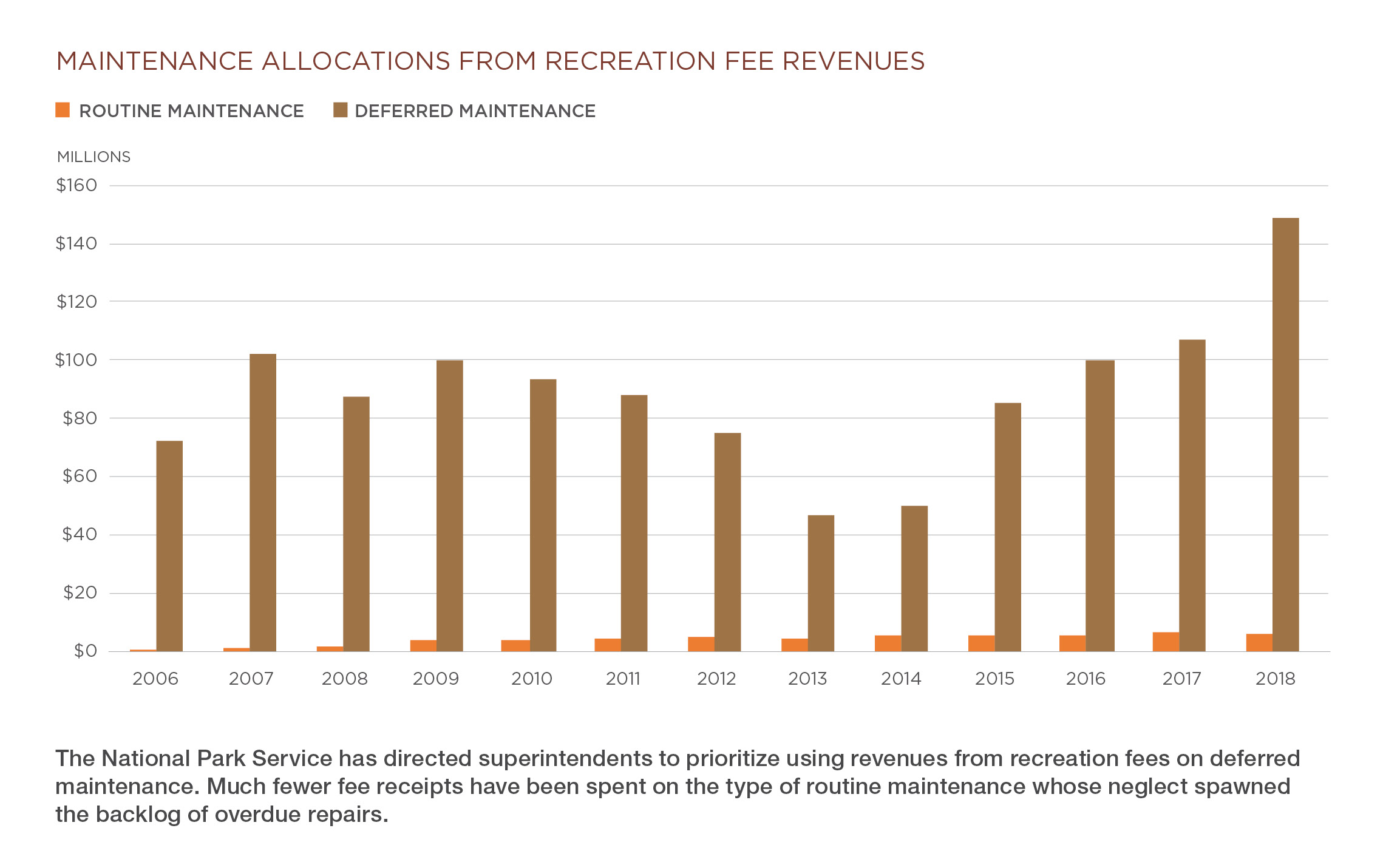

Agency policy has also created a perverse incentive to put off routine maintenance by restricting the way local park managers can use revenues from recreation fees. As one example, the National Park Service directs superintendents to spend at least 55 percent of fee revenues on deferred maintenance, rather than allowing them to decide which on-the-ground needs to prioritize. But this can exacerbate the problem, according to some park managers. Denali National Park Superintendent Don Striker has noted that the policy encourages managers like him to defer maintenance, which he describes as an “expensive, nonsensical choice.” The internal directive means that growth in fee revenues has generated more funding for overdue repairs but contributed much less to regular upkeep such as care of visitor facilities, road work that can prevent long-term damage, or the hiring of permanent employees to conduct routine maintenance. Statute mandates that fee receipts must be used in ways that benefit visitors, but local managers have the best knowledge and context to decide how to accomplish that, whether by addressing deferred projects, performing routine maintenance, or otherwise.

Overcoming these issues and properly caring for public lands over the long run will require rethinking several of these existing approaches. At the fundamental level, maintenance of existing parks ought to take priority over adding new units to the system. Nearly three decades ago, National Park Service Director James Ridenour worried about the “thinning of the blood” that occurs when more parks are created without the means to maintain them. Yet since then, the number of park units has steadily grown without corresponding increases in appropriations. Legislators and the agency should recognize that adding more units to the park system—or expanding existing units—will only make it more difficult to address the underlying maintenance issues.

Lastly, giving land managers more authority in how they can spend fee revenues—while holding them accountable for their decisions—can harness those funds more efficiently. For instance, park superintendents have good information about their maintenance needs and how to meet them, but they need resources and flexibility to address them. Removing internal policies such as the directive to spend 55 percent of fees on deferred maintenance is one way to empower them.

Issue #2: Visitors can help public lands flourish by contributing revenues that support recreation, but reforms can improve the system

Revenues from visitors have become a significant funding source for some sites in recent years, generating additional revenue that goes right back into enhancing the visitor experience. Clarifying that local managers may use fee revenues for operations that benefit visitors is now more important in light of the Great American Outdoors Act, which provides dedicated funding for deferred maintenance, but not for operations.

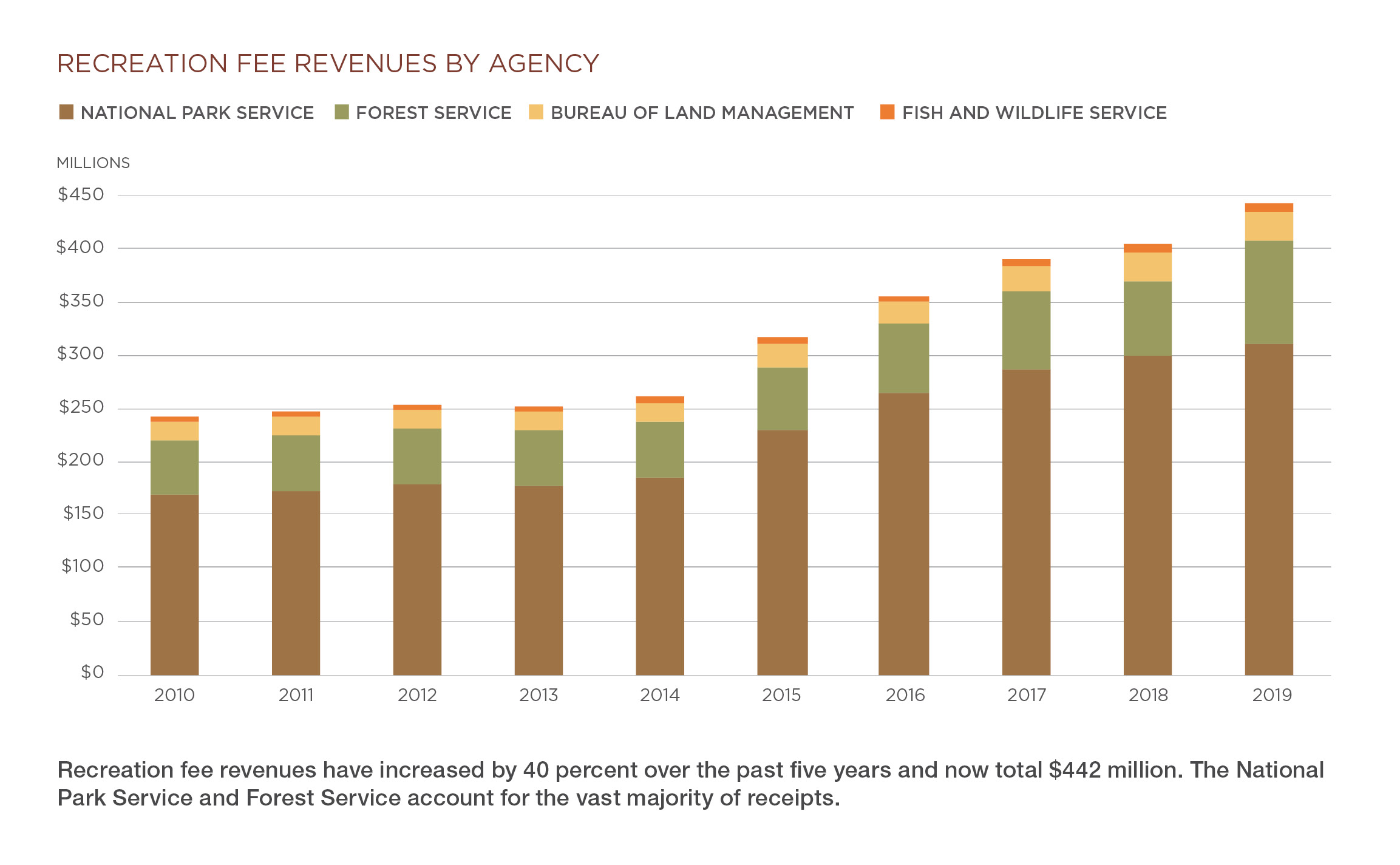

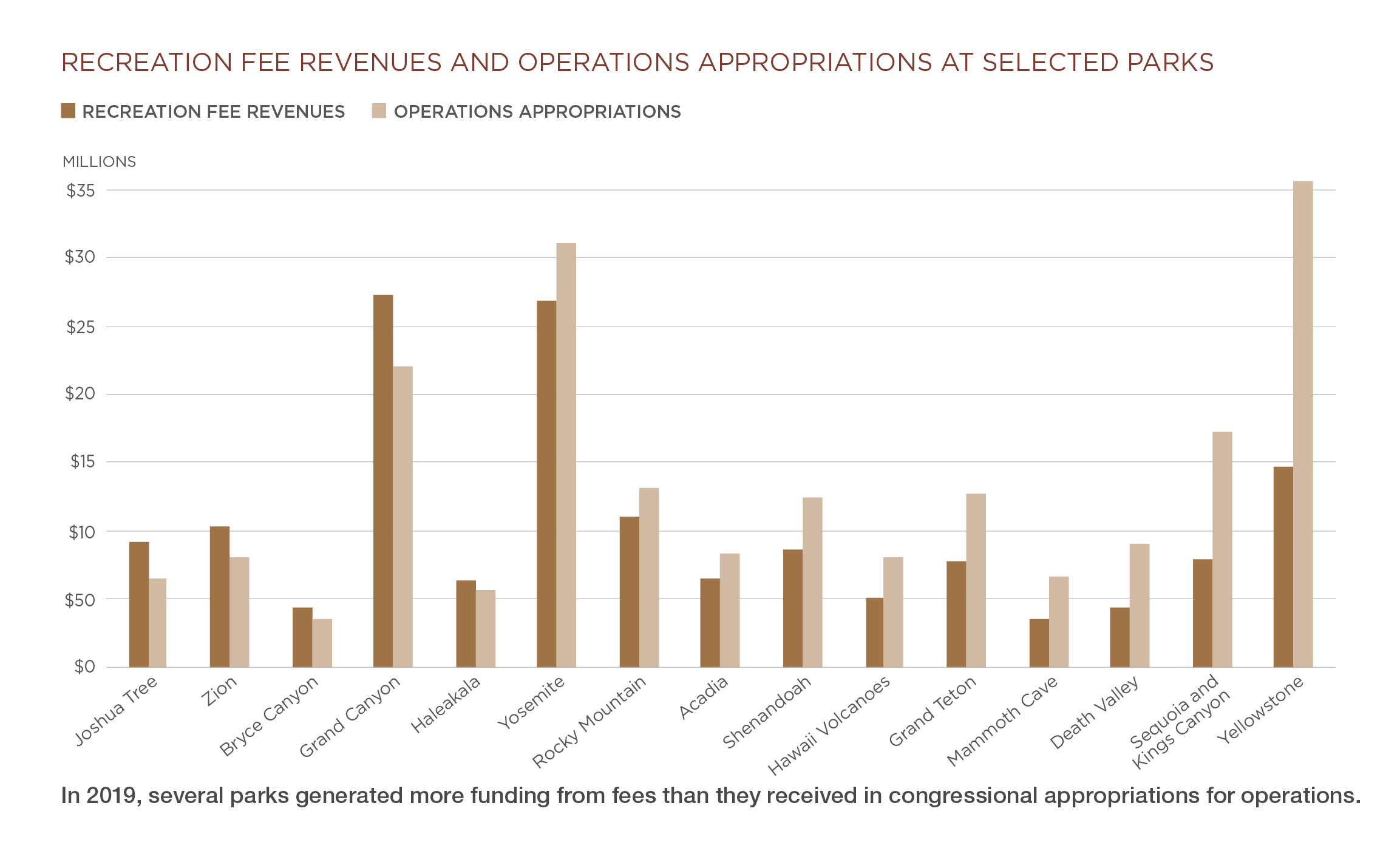

The Federal Lands Recreation Enhancement Act authorizes federal land managers to charge recreation fees for activities like entry to a wildlife refuge or national park or rental of a campsite in a national forest. Under the act, combined fee revenues from all federal land agencies have risen by 40 percent over the past five years, from $316 million to $442 million. In fact, several national parks now generate as much revenue from visitors as they receive in discretionary funding from Congress.

Visitor revenues collected under the act are retained by the site where they were collected to be spent in ways that directly benefit visitors. That means visitor revenues are not subject to many of the political considerations that influence congressional appropriations, which still provide the majority of funding for public land management.

Because local managers can spend fee revenues they generate, decision-making authority over these funds rests with the people managing recreation sites rather than far-away legislators. The model empowers park superintendents, forest supervisors, and other local managers to make decisions about how to best serve visitors, and it removes a degree of political influence from spending decisions. And now that the Great American Outdoors Act has passed, this user-funded model could be an even more important tool to enable park managers to address routine upkeep of repaired infrastructure, thereby protecting investments made under the act.

Several reforms to the recreation fee system, however, are needed to do so. First, Congress should permanently reauthorize the Federal Lands Recreation Enhancement Act, which is set to expire in October 2021. Making the program permanent would give agencies more certainty about future revenue streams from visitors.

Second, park superintendents, forest supervisors, and other public land managers should be given more authority to set fees and spend the revenues they generate. Local managers should be able to easily adjust fees, whether to better compete with other outdoor recreation options, keep pricing in line with inflation, or otherwise. More flexibility in setting fees would promote experimentation in fee structures that could yield useful data, increase revenue that can support visitor services, and result in more equitable pricing by incorporating discounts for locals or other tweaks. Agencies should also consider implementing a surcharge for visitors from overseas, a common practice in other countries that could increase revenues appreciably.

When it comes to spending fees, agencies should trust local management. Oversight is imperative, and managers must be held accountable for their spending decisions. But increasing flexibility will allow the people closest to visitors to decide how to serve them. In some cases, that could mean that managers still decide to prioritize overdue maintenance. Yet clarifying that they may use fees for recurring expenses and permanent employees that enhance visitor enjoyment would also enable them to better use their local knowledge to benefit public land users—a clarification that’s even more important now that the Great American Outdoors Act will provide dedicated funding for overdue maintenance but will not support operational needs.

With public land visitation showing no sign of decline—even amidst the coronavirus pandemic Yellowstone National Park recently had its busiest September and October on record—fee revenues look to be a reliable source of funding for many federal sites in the decades ahead.

Issue #3: Energy revenues are not a reliable source to fund conservation and recreation in the 21st century

Federal energy revenues have long provided significant funding for conservation and recreation on public lands. Indeed, all of the funding for the Great American Outdoors Act comes from energy development on federal lands and offshore waters. Several factors, however, threaten the viability of relying on energy revenues to support such programs, demonstrating the need for alternative funding sources.

When it was established in 1965, the logic of the Land and Water Conservation Fund was to direct a portion of the revenues from extracting publicly owned resources—specifically offshore energy revenues—back into conserving public lands. Now, in addition to mandating full funding for the LWCF, the Great American Outdoors Act has created yet another program to draw down energy revenues: the National Park and Public Land Legacy Restoration Fund. For the next five years, the fund is authorized to receive up to $1.9 billion per year from energy revenues that previously would have gone to the U.S. Treasury. The money will be devoted exclusively to deferred maintenance projects on public lands.

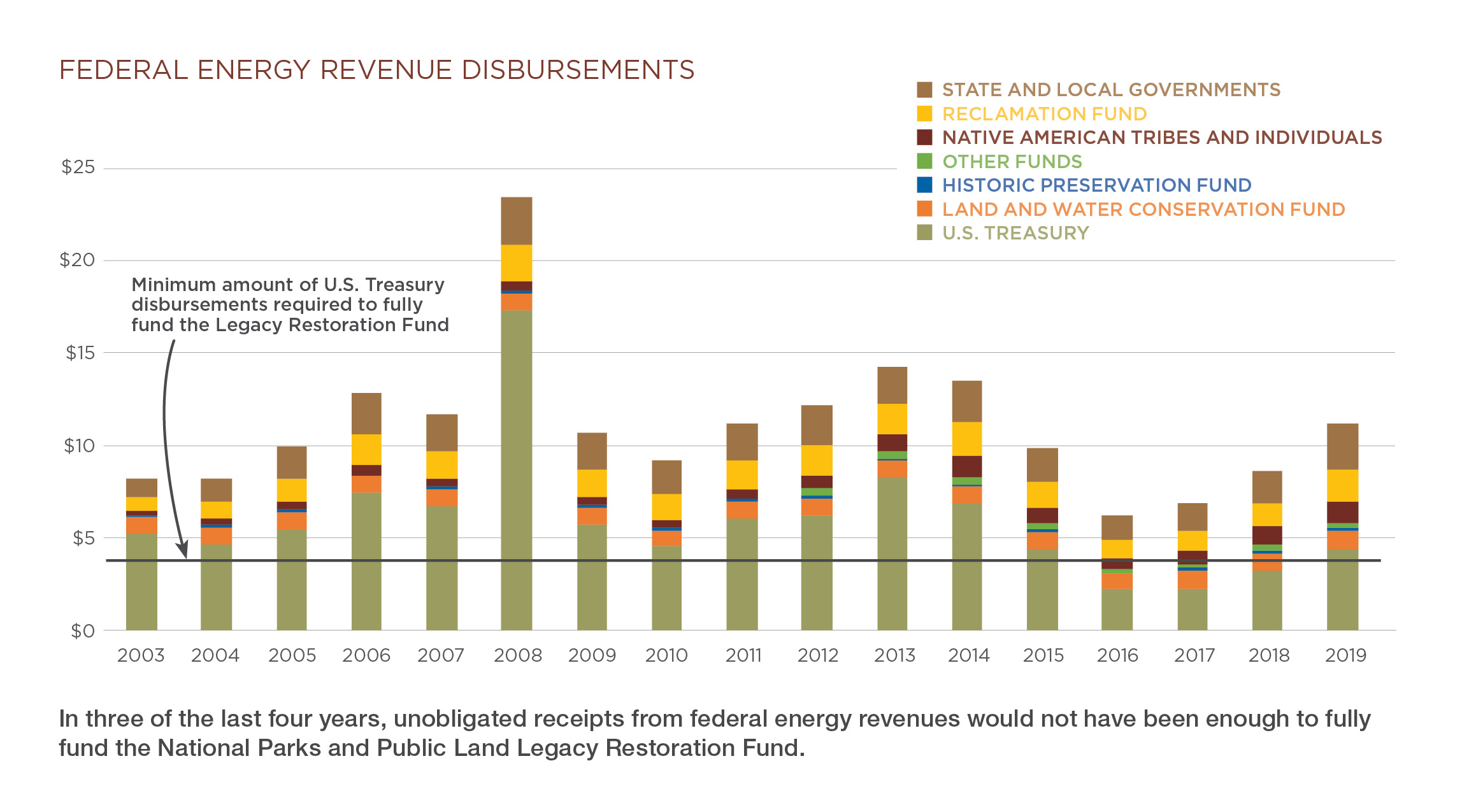

Beyond the LWCF and restoration fund, various federal programs and state and tribal governments already receive federal energy revenues, and more competition over the funds could threaten the programs reliant on them. Other recipients include state and local governments, Native American tribes, the Reclamation Fund, and the Historic Preservation Fund. Additionally, legislators from Gulf States have pushed to keep more of the revenues generated in waters off their coasts. As long as federal energy revenues are flowing, legislators and interest groups seem likely to fight for them to fund their own priorities.

Many conservation and recreation advocates oppose oil and gas drilling while supporting programs that are directly reliant on it. Eventually, unease over the bedrock funding source for these programs must be reckoned with.

With such competition over the use of federal energy revenues, volatility in energy markets can have big effects on conservation funding. Case in point: Recent trends suggest it’s possible energy revenues could be too meager to devote maximum funding to maintenance projects under the Great American Outdoors Act. According to our analysis, federal energy revenues in three of the past four years would have been insufficient to fully top up the restoration fund, primarily due to low oil prices. Low prices over the coming years could hamper its ability to address deferred maintenance on public lands.

Moreover, many policymakers have called for an end to new oil and gas leasing on public lands and waters, creating obvious challenges for the future of energy-funded conservation and recreation programs. In particular, recent calls to ban offshore oil and gas drilling—which generates roughly half of all federal energy revenues—threaten the Land and Water Conservation Fund. Every major Democratic candidate for the 2020 presidential primary pledged to ban new fossil fuel drilling on federal property. As the eventual nominee, Joe Biden was clear on his stance: “No more drilling on federal lands,” he said in a March debate. “No more drilling, including offshore.”

Banning new fossil fuel energy leases would not immediately decimate energy revenues, but once existing leases expire, the effects on federal energy revenues would be significant. When it comes to offshore energy in particular, the National Ocean Industries Association estimates that if new offshore drilling were banned in 2022, it would reduce average offshore energy revenues by 61 percent by 2040, from $7.0 billion to $2.7 billion. If offshore revenues were to fall that drastically, then funding for the LWCF would be under threat.

Those who oppose fossil fuel development might point to revenues from renewable energy as an attractive way to replace the oil and gas money. But while renewables are poised to grow federal revenues in coming decades, even optimistic projections do not have them rivaling current fossil fuel revenues anytime soon. Solar and wind also face some of the same challenges as oil and gas, albeit in different magnitudes and contexts—impacts on wildlife habitat, uncertainty over environmental impact assessments, and “not-in-my-backyard” objections. In light of the challenges, conservationists, recreationists, and lawmakers would all be wise to explore alternative funding approaches.

Public land users are the most promising backers of public lands for the future. The growth of visitor revenues from recreation fees have already demonstrated how user-based funding can provide resources to improve the recreation experience at federal sites. But more could be done to complement or eventually replace the energy-dependent funding used today. At the state level, hunters and anglers already finance the lion’s share of wildlife conservation through purchases of hunting and fishing licenses and revenues from excise taxes on firearms, fishing tackle, boat fuel, and related gear. State fish and wildlife agencies use the revenues to increase outdoor recreation access, protect wildlife habitat, and fund similar purposes. And unlike the programs funded by energy revenues, there is no mandated annual cap on any of these user-generated funds, meaning growth in outdoor recreation translates into more funding for public land management.

The issues presented by the current model warrant innovative and creative ideas that would circumvent the short- and long-term concerns of relying on energy revenues. Policymakers should enlist the help of conservationists and recreationists to expand user-based funding models that can support future public land stewardship. A group with representation from recreationists, conservation groups, outdoor industry, and related parties could weigh the trade-offs of various approaches and explore the most promising options.

Finding another way forward

While the Great American Outdoors Act will bolster public land funding, it could also lay bare some cracks in the foundation. In the short term, mandating full funding for the LWCF and establishing the restoration fund will conserve habitat, promote recreation access, and help address maintenance needs. But more land acquisition through the LWCF also means more land to look after, and federal agencies already struggle to keep up with the current workload. Likewise, making a dent in the deferred maintenance backlog would be great progress, but if routine maintenance remains neglected, the fundamental problem will remain unresolved.

The act also reveals an often-overlooked paradox: Many conservation and recreation advocates oppose oil and gas drilling while supporting programs that are directly reliant on it. Eventually, unease over the bedrock funding source for these programs must be reckoned with. Conservationists and recreationists uncomfortable with the status quo have an incentive to reconsider where funding will come from in the decades ahead. Expanding or creating user-based funding models to support recreation and conservation on public lands could mitigate, at least in part, dependence on energy revenues.

Recreationists and sportsmen groups overwhelmingly supported the Great American Outdoors Act. The fact that it became law during a pandemic, in an election year, and amid an acrimonious and dysfunctional political atmosphere attests to the huge support for conservation and recreation among Americans. If policymakers and stakeholders are willing to search for creative solutions, that same spirit and support can help tackle the issues laid bare by the act, now and for future generations.

[newsletter id=”18″ title=”Receive Our Print Magazine”]