Back in 2006, many beekeepers began to report higher-than-normal losses to their hives over the winter. The mysterious phenomenon was soon given a name—colony collapse disorder (CCD)—and some predicted disaster. Media reports declared a “beepocalypse” or “beemageddon.” A Time cover story envisioned “a world without bees.”

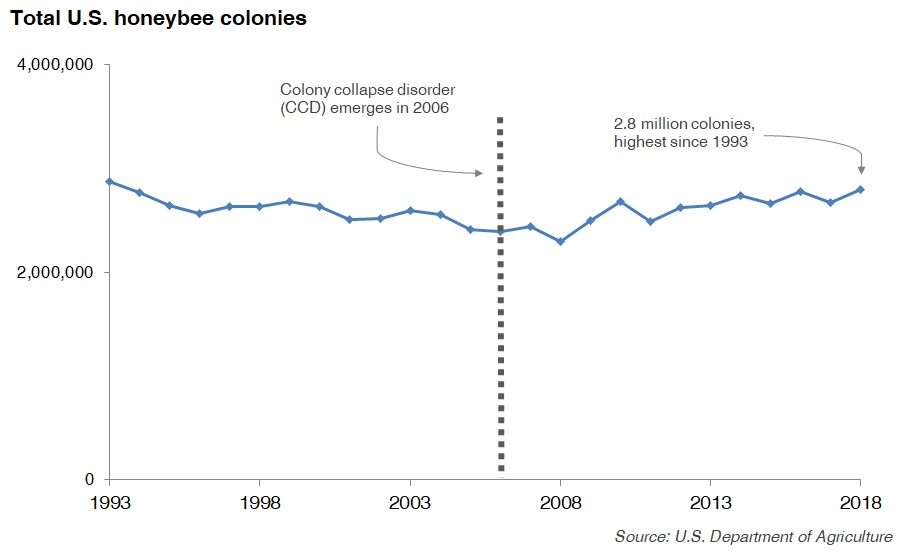

But now, more than a decade later, there has been no “beepocalypse.” Despite an increase in winter honeybee mortality rates, overall U.S. honeybee populations are not declining. According to USDA data, the number of honeybee colonies has been remarkably stable for several decades—and, in fact, the latest data show that colonies are at their highest level since 1993.

How could this bee? A new study published this week in the Journal of the Association of Environmental and Resource Economists by economists Walter Thurman and Randal Rucker (both senior fellows at PERC) and Oregon State University entomologist Michael Burgett helps explain what’s going on.

The researchers analyze various economic indicators related to honeybee operations—from total colony numbers and honey production to honey prices and pollination fees—to assess how markets have responded to problems such as colony collapse. Their overall conclusion: “We find strong evidence of adaptation in these markets and remarkably little to suggest dramatic and widespread economic effects from CCD.” They further explain:

While the tone of much discussion of pollinators and their health is bleak, our results give cause for considerable optimism, at least for the economically dominant honey bee. We find that CCD has had measurable impacts in only one economically important segment of the industry: pollination fees for almonds. As a whole, the impacts are small relative to our priors. Moreover, and in stark contrast to perceptions formed from surveying media sources as well as a substantial body of academic literature, we find that CCD has not had measurable effects on honey production, input prices, or even numbers of bee colonies. We attribute these findings to a factor largely overlooked in the scientific and popular literature on pollinator decline: the ability of well-functioning markets to adapt quickly to environmental shocks and to mitigate their potential negative impacts.

As the study makes clear, the recent increase in honeybee mortality rates is only part of the story. Thanks to a robust market for pollination services, beekeepers have adapted to these changes by actively rebuilding—and even increasing—their colonies in the face of CCD, often quickly and at remarkably little cost. As I explained in a recent essay for Reason magazine:

Rebuilding lost colonies is a routine part of modern beekeeping. The most common method involves splitting a healthy colony into multiple hives—a process that beekeepers call “making increase.” The new hives, known as “nucs” or “splits,” require a new fertilized queen bee, which can be purchased from a commercial queen breeder. These breeders produce hundreds of thousands of queen bees each year. A new fertilized queen typically costs about $19 and can be shipped to beekeepers overnight. (One breeder’s online ad touts its queens as “very prolific, known for their rapid spring buildup, and…extremely gentle.”) As an alternative to purchasing queens, beekeepers can produce their own queens by feeding royal jelly to larvae.

Beekeepers regularly split their hives prior to the start of pollination season or later in the summer in anticipation of winter losses. The new hives quickly produce a new brood, which in about six weeks can be strong enough to pollinate crops. Often, beekeepers can replace more bees by splitting hives than they lose over the winter, resulting in no net loss to their colonies.

Another way to rebuild a colony is to purchase “packaged bees” to replace an empty hive. (A 3-pound package typically costs about $90 and includes roughly 12,000 worker bees and a fertilized queen.) A third method is to replace an older queen with a new one. A queen bee is a productive egg-layer for one or two seasons; after that, replacing her will reinvigorate the health of the hive. If the new queen is accepted—as she often is when an experienced beekeeper installs her—the hive can be productive right away.

The result is that CCD has had almost no discernible economic effect. The one exception is for the pollination fees that beekeepers charge almond producers—but even that effect has had a negligible impact on consumers. The researchers estimate that “the CCD-induced increase in pollination fees increased the retail price of a $7-per-pound can of Smokehouse Almonds by approximately 1.2% or 8.4¢.”

The research helps us better understand how markets can respond to environmental changes. Where well-functioning markets exist, as they do for managed honeybees, humans can adapt quickly and effectively to environmental shocks. Where markets do not exist, such as for wild pollinators, adaptation may be more difficult.

So next time you buy a jar of honey or eat one of the hundreds of foods that come from crops that are pollinated by honeybees, give thanks to the beekeepers that have proven so resilient. Thanks to them, the “bee-pocalypse” will have to wait.