Highlights

- Fuel treatment projects designed to reduce wildfire risks, including mechanical treatments and prescribed burns, often take longer to implement than other U.S. Forest Service projects because they are more likely to require rigorous environmental review or be litigated.

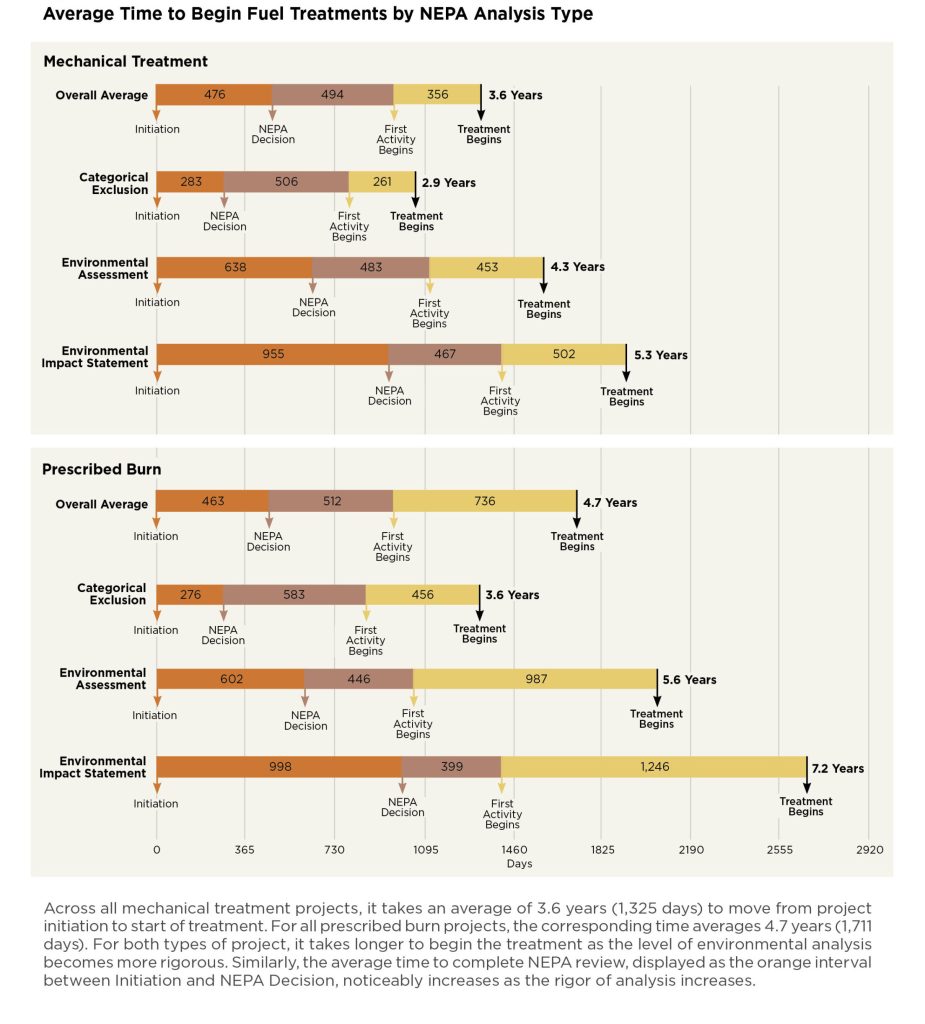

- Once the Forest Service initiates the environmental review process, it takes an average of 3.6 years to begin a mechanical treatment and 4.7 years to begin a prescribed burn.

- For projects that require environmental impact statements—the most rigorous form of review—the time from initiation to implementation averages 5.3 years for mechanical treatments and 7.2 years for prescribed burns.

- Given the time it takes to conduct environmental reviews and implement fuel treatments, it is unlikely that the Forest Service will be able to achieve its goal of treating an additional 20 million acres over the next 10 years.

- Click here to download the full report.

Report Summary

Wildfires are burning record numbers of acres in the western United States each year. More than 10 million acres burned nationwide in three of the past seven years, most of them in the West. In California, nine of the 20 largest wildfires in the state’s history have burned in the past two years. Changing patterns of temperature and precipitation, coupled with growing populations near fire-prone landscapes, make wildfires increasingly destructive and costly. The arid climate and vast federal estate make western states especially prone to large wildfires.

More than half of the land in the 11 contiguous western states is federally owned and managed. While multiple federal agencies must deal with wildfires, the largest burden falls on the U.S. Forest Service. Of the 640 million acres of federal land in the United States, the Forest Service manages 193 million. In 2020, 7.1 million acres of federal land burned in wildfires, including 4.8 million acres of Forest Service land.

Wildland fire management is the top budget item for the Forest Service, with suppression costs reaching $1.76 billion in 2020. Increasingly, legislators, agency officials, and forest science researchers are concluding that more proactive fire mitigation activities are needed to lessen the severity and costs of western wildfires. For instance, a new initiative by the Biden administration aims to carry out fuel treatments on an additional 50 million acres over the next 10 years to reduce extreme wildfire risks, including an additional 20 million acres of national forest lands.

To preemptively reduce the impacts of large and costly wildfires, forest managers use methods that remove fuels—brush, trees, and other flammable materials—to lessen the intensity of burns. The two most common fuel treatments are prescribed burns and mechanical treatments. The effectiveness of these measures was demonstrated in 2021 during Oregon’s Bootleg Fire, which ultimately burned 400,000 acres. Firefighters reported that where both treatments had been applied, fire intensity was reduced, the crowns of trees were left intact, and the blaze became a more manageable ground fire. Such low-intensity fires, which frequently burned in the West before aggressive fire suppression policies were adopted, are ecologically important. Managed forests are more resilient to drought, high temperatures, fire, and insects.

In 2021, several proposed treatment areas burned in large wildfires while facing delays from environmental reviews and litigation

While these approaches have proven effective at reducing the likelihood and severity of wildfire, the Forest Service has not been able to undertake mitigation activities at the scale needed to address the threat in a meaningful way. Indeed, reports from the Bootleg Fire suggested that an area where scheduled prescribed burns had been delayed suffered more damage than areas where treatments had been completed. As of 2018, 80 million acres of national forest land needed restoration to reduce susceptibility to wildfire, disease, and insects, according to Forest Service officials, yet the agency has treated just 2 million acres annually in recent decades.

Forest Service estimates suggest that an investment of $5-$6 billion over 10 years would be required to perform fuel treatments on all of the highest-priority areas. Regulatory processes and litigation, however, pose significant barriers to achieving these mitigation goals. One survey of forest managers suggested that environmental policies are viewed as an important hurdle to prescribed burns, a key method of reducing fuels. Regulatory processes that increase the time between identifying and implementing treatments exacerbate wildfire risk and limit the flexibility of managers to use new information to quickly address emerging risk. In 2021, for example, several proposed treatment areas burned in large wildfires while facing delays from environmental review and litigation.

This policy brief examines the amount of time it takes the U.S. Forest Service to implement fuel treatment projects while navigating the requirements of the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA). NEPA is a procedural law that requires federal agencies to assess the environmental impacts of proposed actions. Under NEPA, proposed projects are treated in one of three ways: Projects determined to have no significant impacts receive categorical exclusion (CE) from more stringent review. For projects with uncertain impacts, agencies must conduct an environmental assessment (EA). For projects deemed to cause significant environmental impacts, federal agencies must complete an environmental impact statement (EIS), the most stringent type of review under the law. During an EIS, agencies gather information about expected project impacts to the quality of the human environment, solicit public comments, and respond to all substantive comments. While only some fuel-reduction activities require an EIS, the NEPA process can be time-consuming and resource-intensive for all projects.

The NEPA process increases the time it takes to implement fuel treatments through direct and indirect channels. Direct effects come from administrative and processing time associated with preparing and approving an analysis, plus potential objections and litigation of the agency’s analysis. Indirect delays occur when agency officials proactively attempt to ward off future controversy, objections, and litigation through additional processing time and analysis.

Advocacy groups, firms, and the general public can file objections to NEPA decisions to the Forest Service and, once that avenue is exhausted, can also file lawsuits to overturn decisions or compel additional analysis. Objecting is a pre-decision process designed to avoid future litigation by allowing the agency to resolve concerns over a project before a NEPA decision has been made. Although most projects are not litigated, the depth of analysis and time spent on the NEPA process is commonly based on the threat of litigation, as well as the level of public and political interest and defensibility in court.

This brief compiles new NEPA data to examine the duration of administrative review for Forest Service wildfire mitigation activities. It documents how long it takes to implement fuel treatment projects and then separates out the portion that involves NEPA review from other factors, including litigation.