This special issue of PERC Reports explores the thorny issues of forest management, wildfire mitigation, and regulatory reform. Read the full issue.

If you were to walk through the forests of the American West in the 19th century, you would see a landscape vastly different from the one that exists today: Scattered trees mixed with open meadows. Mosaics of young growth interspersed with mature stands. Fire scars from frequent, low-intensity wildfires, many of them set by Native Americans.

Visitors to the region took note of these features. The Lewis and Clark expedition observed fires set by Native Americans in the upper Missouri River drainages. John Muir described how you could ride on horseback through the “inviting openness” of the Sierra woods with little difficulty. Carleton Watkins’ photos from Yosemite Valley featured scenic meadows thinly dotted with trees.

In much of the West today, that is no longer the case. A century of fire suppression has turned many western forests into dense, fire-prone thickets. Conifers have encroached on or consumed open meadows. And shade-tolerant species such as Douglas fir have choked out old-growth stands of ponderosa pines. One recent study found that the West’s dry forests are six to seven times more crowded than they were a century ago, stocked with trees that are 50 percent smaller.

These dense forests, combined with a warmer climate, can lead to catastrophic wildfires. Dangerous fuel loads allow fires to reach the tree canopy, where they spread rapidly in thick forests and inflict significant damage to ecosystems, watersheds, and nearby communities. They also emit large amounts of smoke and other air pollution. By one estimate, fires in the western United States last summer released 130 million tons of carbon dioxide—roughly a year’s worth of pollution from 25 million cars.

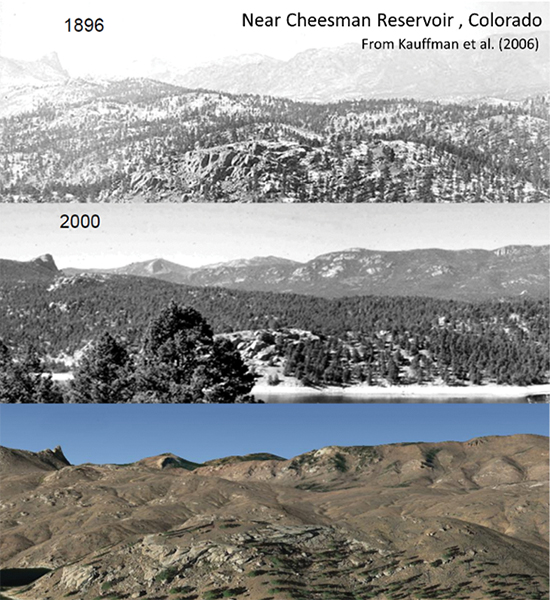

A century of change: Today’s fires can burn so large, and so intense, that they threaten the ability of America’s forests to regenerate. Colorado’s Cheesman Reservoir (shown above), which supplies water to the city of Denver, was once surrounded by open woodlands scattered with ponderosa pines due to frequent, low-intensity fires. By 2000, a dense forest had built up, fueling a severe fire that burned in 2002. The fire burned so hot that, by 2020, the forest hadn’t recovered. The landscape is now dominated by shrubs.

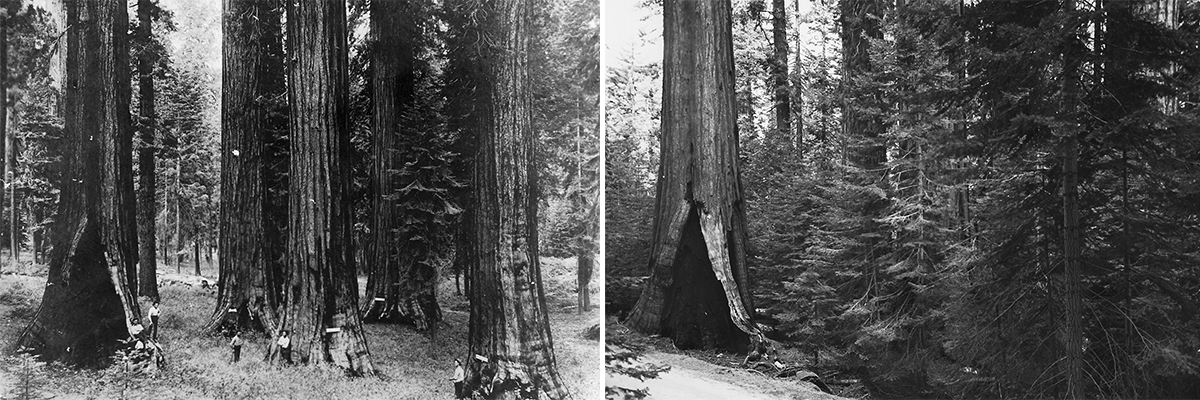

Giant sequoias of Mariposa Grove: By the 1960s, Yosemite’s giant sequoia groves (shown above) were no longer regenerating. The trees rely on disturbances such as fire to regenerate, but the National Park Service was suppressing all fires in the park. In the past, frequent ground fires kept other species under control and helped open sequoia cones to scatter seeds. Without these fires, shade-tolerant white firs began outcompeting sequoia seedlings, creating a dangerous fuel load that threatens sequoias by allowing fire to reach their crowns. Last year, thousands of giant sequoias were killed by wildfires in nearby Sequoia National Park.

Fuel treatments work: There is growing recognition among fire experts that restoring historic forest conditions through selective thinning and prescribed burning can reduce the risks of catastrophic wildfires by making forests more fire resilient. As the Bootleg Fire ripped through the Fremont-Winema National Forest in southern Oregon last year, these methods paid off. In places where prescribed fires and forest thinning had been carried out, firefighters reported that flames returned to the ground, where they moved slower, did less damage, and were easier to fight.

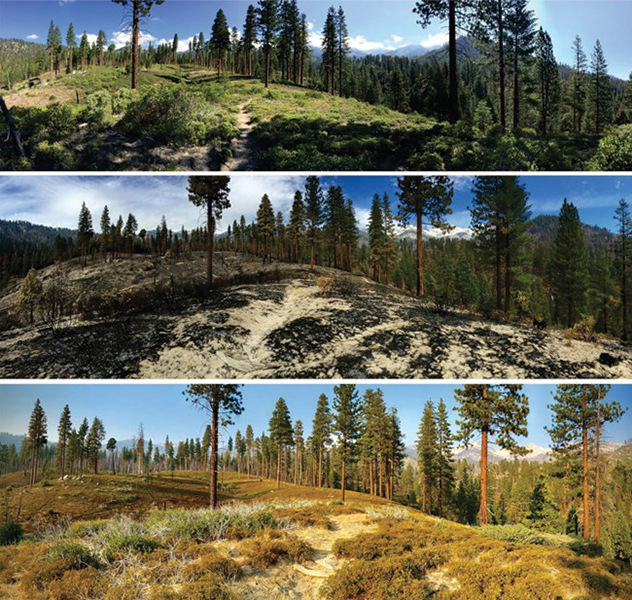

The need for “good fire”: Prescribed burning is an effective way to reduce dangerous fuel loads and promote fire-resilient forests. In this series of images from a prescribed burn project in Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks in California, the benefits of these “good fires” are on display. The top photo shows an area of the park that was treated with a prescribed burn. The middle photo was taken in 2015 after the Rough Fire burned through the area. The bottom photo was captured in 2020, showing the landscape’s resilience. Despite the wildfire, the trees in the area remain healthy and standing.

Fixing America’s forests: Dense forests, such as the ones in Arizona shown on top, fuel large wildfires that can be catastrophic for people and ecosystems alike, while forests that have been thinned present lower risks of extreme wildfire. Mechanical thinning projects reduce forest density by removing small or unhealthy trees while leaving large, mature trees standing, as seen in another Arizona forest on the bottom, resulting in a landscape that resembles the western forests of past centuries. Thinning and complementary restoration efforts help protect watersheds, enhance wildlife habitat, store carbon, and increase forest resiliency to pests, disease, and other threats.