This article was originally published by the Frontier Institute.

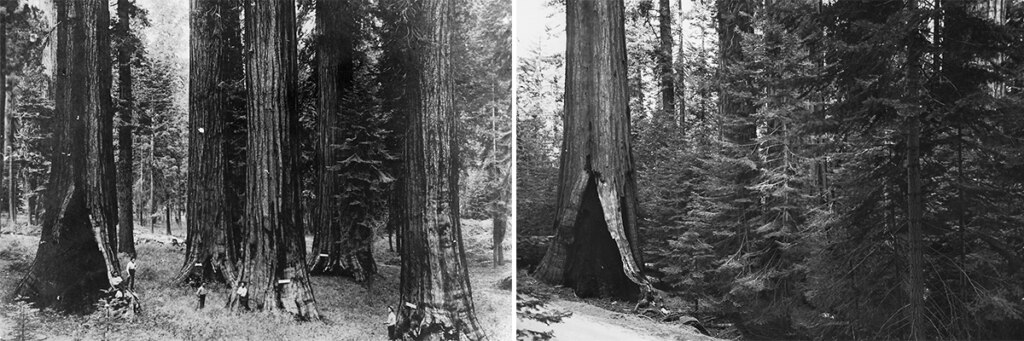

The plight of the giant sequoias captures the wildfire crisis ravaging the West. Though the massive trees have coexisted with fire for centuries, the higher-severity fires in recent years have killed up to 10,000 sequoias, or approximately a fifth of the species.

Last summer General Sherman—the world’s largest tree—in Sequoia National Park was one of the numerous giant sequoias wrapped in protective aluminum foil in a frantic effort to protect the tree as a lightning-caused wildfire swept through the area. Though sequoias rely on disturbances such as fire to regenerate, this demonstrates how decades of fire suppression and fuel buildup has led to catastrophic wildfires destructive enough to threaten even the world’s largest tree.

The good news is that the fate of the giant sequoias can be changed. Proactive forest management has proven a successful way to reduce wildfire risk and intensity. Earlier this month, the Washburn Fire threatened the famous giant sequoias of Yosemite National Park’s Mariposa Grove. The grove is a national treasure, with some of the trees being more than 2,000 years old, losing it would be a tragedy. Yet as the Washburn Fire burned through, the grove survived.

What spared the Mariposa Grove? Fuel reduction treatments. As Yosemite forest ecologist and firefighter Garrett Dickman explained, “the really obvious takeaway is we’ve been preparing for this fire for 50 years. And that preparation is saving these trees. We haven’t had to wrap trees or really put firefighters at tremendous risk. They’ve been able to engage safely because those fuel reduction treatments have proven to be so effective.”

Fuel reduction treatments including mechanical thinning, prescribed burns, and removing duff and other buildup from the base of large trees have proven successful at reducing wildfire intensity and overall risk among sequoias and other types of forests.

But before any saw or drip torch can touch a federal forest, a restoration project spends a ridiculously long time being analyzed, approved, and funded. New research from PERC found that once the Forest Service initiates the environmental review process, it takes an average of 3.6 years to actually begin a mechanical treatment on the ground and 4.7 years to begin a prescribed burn—and those numbers increase significantly if an environmental impact statement is required or if the project is litigated. A proposed restoration project in Yosemite that would have reduced wildfire fuels in areas including the Merced and Tuolumne groves of giant sequoias, was halted a few weeks ago due to litigation, greatly delaying important restoration work.

But the sequoias don’t have the luxury of time. Work needs to be done now to protect sequoia groves from the real and present wildfire threat. The good news is that policymakers are starting to pay attention to the need for active forest restoration efforts. The Forest Service announced last Thursday that it is initiating emergency fuels reduction treatments to protect giant sequoias and is using existing authorities to expedite the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) environmental review process to more rapidly deploy treatments on the ground. A bipartisan group of Representatives also introduced the Save Our Sequoias Act (H.R.8168) which would alleviate red tape and promote collaborations to conduct forest restoration activities to protect the trees.

The destruction of sequoias in recent years must serve as a wake-up call to the need to reduce the risk of catastrophic wildfires. Forests across the west are facing similar threats as California’s giant sequoias. By actively working to restore forest ecosystems and reducing fuel buildups, we can preserve our nation’s cherished forests.