This special issue of PERC Reports explores the West’s water crisis and how markets can address today’s shortages. Read the full issue.

First, there was one dead body. Then, a few days later, another—both recovered last May in the mud exposed by the receding waters of Lake Mead, near Las Vegas. One corpse was discovered inside a metal barrel, the result of an apparent homicide that detectives believe occurred in the early 1980s based on the victim’s clothing and footwear. The other was skeletal remains half buried in a newly surfaced sandbar. “There is a very good chance as the water level drops that we are going to find additional human remains,” said a Las Vegas police lieutenant at the time.

It could have been a scene from Roman Polanski’s 1974 classic Chinatown. But the bodies—six of which had been recovered by October—are a gruesome illustration of a grim reality: The western United States is in the grip of a deep and prolonged drought, causing unprecedented water shortages. The Southwest just experienced its driest two decades in 1,200 years, according to one recent study. This past year was more of the same, if not worse. California started 2022 with its driest first five months on record. As of October, more than 80 percent of the country is facing abnormally dry or worse drought conditions, according to the U.S. Drought Monitor—the highest percentage since the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration began tracking the data.

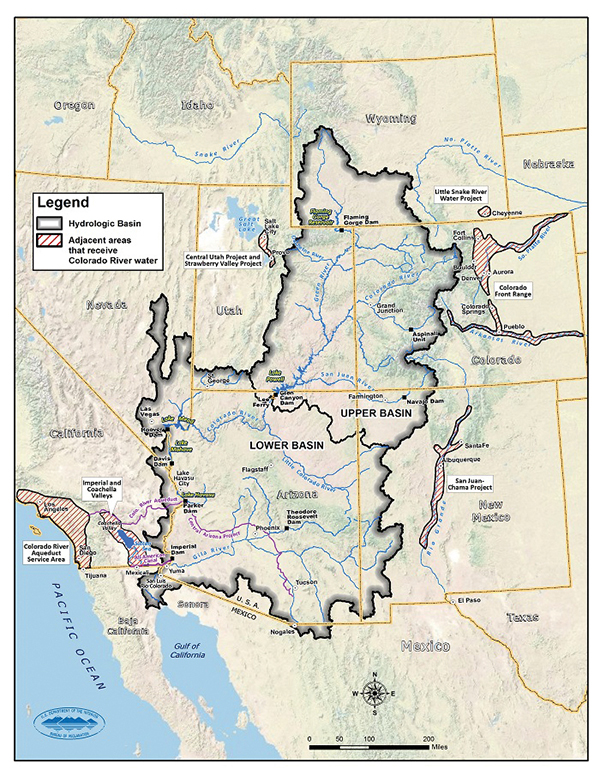

The drought is especially pronounced in the Colorado River Basin, which supplies water to 40 million people across seven states and Mexico and provides irrigation to more than 5 million acres of farmland. Water levels in Lake Mead and Lake Powell, the basin’s two largest reservoirs, have dropped to their lowest levels since they were filled in the early to mid 20th century. In response, the federal government has recently issued its first formal shortage declarations for the river, triggering a series of mandatory water-delivery reductions. Additional cutbacks are likely coming soon.

The region’s water supply has plummeted to levels unanticipated even just a few years ago. At the start of the 21st century, Lakes Mead and Powell were nearly full. Now both are below 30 percent capacity. If water levels drop much farther, officials warn, the dams’ turbines will no longer be able to generate electricity, creating additional power-supply challenges for a region already at elevated risk of rolling blackouts this summer because of extreme heat and increased reliance on intermittent wind and solar energy. And if they decline farther still, the reservoirs could reach “dead pool” conditions, in which water is unable to flow downstream from the dams.

The consequences of the drought are being felt throughout the West. In Utah, the Great Salt Lake dipped to a historic low in 2022, exposing the lakebed to windstorms that pick up dust containing arsenic and other toxic elements and blow it to nearby cities on the Wasatch Front. New Mexico’s parched landscape helped fuel the largest wildfire ever recorded in state history. And in California, a lack of surface water is accelerating groundwater pumping that is depleting aquifers and causing the land itself to sink in some areas.

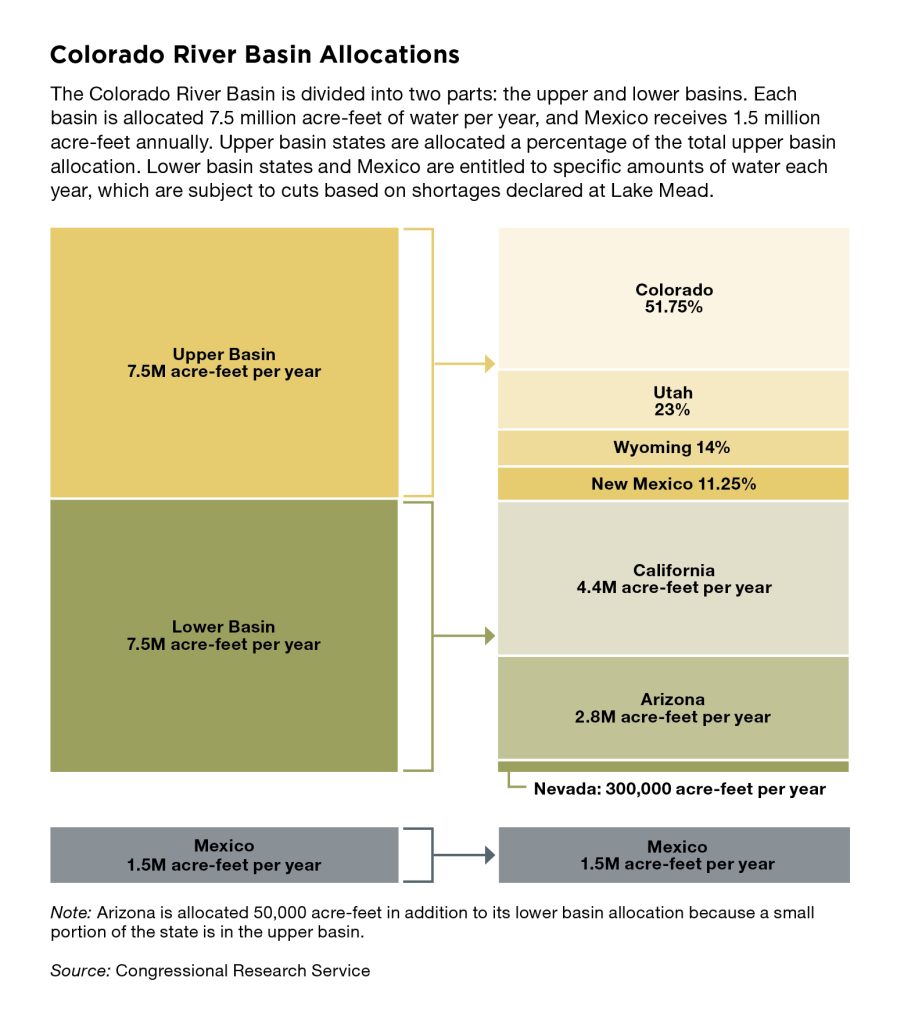

Drought is the proximate cause of today’s water shortages, but in the Colorado River Basin, the root of the problem dates back a century. In 1922, the Colorado River Compact divvied up the river’s water, allocating 7.5 million acre-feet to the Upper Basin states of Wyoming, Utah, Colorado, and New Mexico and 7.5 million acre-feet to the Lower Basin states of California, Arizona, and Nevada. What water managers didn’t understand at the time was that the river’s flows had been abnormally high. The compact anticipated annual flows of at least 17 million acre-feet; this century the river has averaged closer to 12 million acre-feet. The compact’s allocations, it turns out, were made during what we now know was the region’s wettest period in the past 500 years.

By the second half of the 20th century, it was clear the river had been overallocated—but the damage was done. Renegotiating the compact has proven difficult, since infrastructure and industries have been built around the expectation of the compact’s original water allocations. And as climate change appears to be locking in a drier future for the region—a phenomenon some have termed “aridification,” to distinguish it from temporary drought—the problem has gotten worse. Water consumption from the basin has exceeded supply by an average of 1.1 million acre-feet each year over the past decade—a gap equal to four Las Vegases’ worth of water. Today, the Colorado River typically runs dry long before it reaches the Gulf of California.

The story is much the same throughout most of the American West: There are more water rights on paper than there is actual water to go around, and everyone has legal arguments for why cuts should fall on others instead of themselves. But if the arid West is to adapt to its even drier future, it’s going to have to find ways to use its limited water resources more effectively through cooperation instead of litigation, and nearly everyone is going to have to do with less.

Doing More with Less

When it comes to water in the West, navigating the future requires understanding the past. Western water rights are allocated under a doctrine known as “prior appropriation,” in which water was claimed by early settlers on a first-come, first-served basis as long as it was put to a “beneficial use.” This typically meant diverting water to irrigate crops. The oldest, most senior water-right claims—often of agricultural producers—get first dibs during times of scarcity, regardless of whether the claimants are upstream or downstream of other users. Water that is not used may be deemed abandoned and reallocated to someone else.

Today, new challenges are emerging. In addition to drought, the growth of western cities has required finding ways to meet urban water demands, often by transferring water from agricultural to municipal uses. At the same time, environmental and recreational interests have placed new demands on conserving water for fish and wildlife habitat. And groundwater resources, which are a primary water source for many western communities, are being depleted faster than they can be replenished—all at a time when there is less water to go around.

At a Senate hearing in June 2022, Bureau of Reclamation commissioner Camille Touton said the Colorado River Basin states will need to conserve 2 million to 4 million acre-feet of water in 2023 to reduce the risk that supplies will reach critically low levels. An August deadline came and went, however, with no agreement hashed out among the states. As populations continue to grow in western states, and global food shortages stemming from the war in Ukraine put pressure on U.S. agriculture, the question is where those cuts will come from.

In the face of such challenges, however, there are reasons for optimism. John Fleck, a prominent western water writer, has long argued that the West has a remarkable and underappreciated ability to adapt to water scarcity. “When people have less water,” Fleck has written, “they use less water”—whether through wastewater recycling, stormwater capture, lawn buybacks, water-banking agreements, or just good old-fashioned conservation. Predictions of catastrophe are often overstated by the media, according to Fleck.

“Fear of water shortage is greater than reality, as communities underestimate their ability to cope when supplies run dry,” Fleck wrote in 2016. To capitalize on this flexibility, he said, “we need to develop institutions that both respect current water users and provide tools for moving water around more easily” to where it’s most valued. That can include the difficult tasks of arranging deals between willing buyers and sellers, agreeing on how to measure saved water and get it to alternative uses, and sometimes even changing the rules so that water can be transferred from one use to another.

Fleck pointed to a surprising fact that is often overlooked: Water use in the Colorado River Basin has declined over the past two decades, even as the region’s population has grown. In fact, the same is true across the West as well as nationwide: Overall U.S. water use has fallen 25 percent since 1980, even as population increased more than 40 percent. Clearly, more conservation will be needed—drought-induced reductions in the Colorado River’s water supply, for example, have exceeded the basin’s water-use declines—but Fleck’s point is that we have the ability to reduce water consumption, often by a lot.

In the West, part of the reason for the overall decline in water use is that subdivisions are less water-intensive than agricultural fields, especially those for thirsty (and often lower-value) crops such as alfalfa and cotton. To facilitate these changes, institutions have to be in place that allow water rights to be leased or transferred from agricultural to municipal uses. Arizona has drastically cut its water use in this way, in large part by building houses instead of growing cotton, with water rights exchanged between willing buyers and sellers.

Another reason is that cities have become more water-savvy, often by recycling wastewater, conserving storm-water runoff, or investing in more-efficient water-distribution systems. Fleck’s hometown of Albuquerque is illustrative: Even as the city’s population has grown during the recent drought, its total water use has declined. This decoupling of water from growth has occurred in city after city. Las Vegas, often derided as a symbol of environmental waste, has cut its per capita water use almost in half since 2002, and its overall water use has declined as well. Phoenix’s water consumption has declined by one-third since 1980, even while its population has doubled. San Diego now uses 40 percent less water than it did in 2007.

All of this points to the impressive ability of water users to adapt to scarcity without sacrificing economic growth. The biggest opportunity to continue this progress is in the agricultural sector, which uses more than 80 percent of the water consumed in the West. Farmers also have found ways to increase yields and earnings in the face of shrinking water supplies, sometimes by switching to less water-intensive crops or installing more-efficient irrigation systems. The challenge, according to Fleck, is “getting the institutional infrastructure right” to facilitate such adaptations and to move water to where it’s most needed.

Use It or Lose It

Unfortunately, western water laws can discourage conservation and limit the flexibility to move water to higher-valued uses. In many cases, legal rules can discourage or prevent water-right holders from leasing or selling their conserved water. To encourage greater adaptation, water policies should allow someone who needs water to pay another user to forgo water use or to invest in water conservation. But, in reality, a variety of procedural and regulatory requirements can thwart even the most sensible win–win water trades.

Part of the challenge is that, under the prior-appropriation doctrine, the status of conserved water is often unclear. For example, if a water user adopts more efficient practices that result in unused water, the “beneficial-use” requirement could cause that user to lose that portion of their water right. In some states, farmers who take steps to save water—perhaps by updating an irrigation system or lining leaky ditches—risk forfeiting the unused amount. “Use it or lose it” rules can also make it difficult to lease or acquire water for nonuse purposes, such as boosting instream flows for fish and wildlife habitat.

Regulatory procedures also impede the flow of water to other uses. Transfers typically require the pre-approval of regulators, and numerous stakeholders can block trades. Regulators must consider a range of potential impacts of any water transfer, including how a water-use change would affect other rights-holders, the environmental impact of the transfer, and the economic effects that the transfer might have on the surrounding community.

In practice, these rules create significant obstacles to moving water to where it’s most needed. They can also discourage simple, short-term exchanges that have potentially big water-saving benefits. For example, an alfalfa farmer may agree to forgo irrigation in a dry year to send water to a nearby city, or an environmental group may lease agricultural water during low-flow periods to protect vulnerable fish populations. According to Mammoth Water, a company that facilitates water trades, short-term-lease approvals can often take a year or more—sometimes longer than the proposed lease is for, defeating the whole purpose of the exchange.

The transaction costs of trading water are preventing more widespread adoption of water markets. As a result, much of the West’s water gets spread on low-value agricultural crops, and users in need of additional water are often forced to tap into limited groundwater reserves, which are typically open-access and prone to overuse.

Reducing barriers to water trading would enable the West to better adapt to water shortages while also addressing environmental concerns. A 2018 report published by PERC and the R Street Institute offered several reform ideas, including allowing users to keep or sell unused water, eliminating restrictions on changing the use of water, expediting short-term lease approvals, and recognizing aquifer storage as a valid water use. In California, for example, recharging depleted groundwater aquifers is not considered a “beneficial use” and therefore is not a legally valid use of water rights.

There is also the issue of prices. Higher prices are an obvious way to encourage conservation, but some western cities have been reluctant to raise rates, even amid dire shortages. Salt Lake City, for example, has one of the lowest per-gallon water rates in the country—and, not surprisingly, its residents consume more water than those in most other desert cities. Agricultural water prices in the West are even lower—sometimes only a few pennies per thousand gallons—owing in part to federally subsidized water projects and limitations on transferring water to municipal uses that are valued more highly. Pricing water efficiently for both agriculture and urban uses is crucial to managing scarce water resources, especially during drought.

Despite these obstacles, progress is happening. In parts of the West, water districts are experimenting with paying farmers to temporarily fallow some fields or to plant crops that are less water-intensive (see Tate Watkins’ essay on page 16). In California, groundwater markets are emerging to sustainably manage aquifers, with tradeable pumping rights allocated to users within a groundwater basin (see Andrew Ayres’ essay on page 30). And in 2022, Utah began allowing water rights to be leased by environmental groups for conservation purposes, to leave more water in streams for fish and wildlife habitat (see Tim Hawkes’ essay on page 38).

Technological advancements also give water users the ability to do more with less. Recycling treated wastewater has proven to be an effective water-saving tool in many western communities. Desalination is a viable solution for some coastal cities—although building desalination plants has proven difficult in places such as California.

And there are market innovations as well: Online water-rights marketplaces and clearinghouses can reduce the transaction costs of trading water, and new satellite-based methods to measure consumptive water use can help address measurement and verification challenges that prevented otherwise viable water transfers in the past. Both of these tools are emerging in response to today’s shortages.

Incentives to Conserve

There is a classic paradox in economics: Water is cheap, but diamonds are expensive, though one is essential for life and the other is not. Even Adam Smith was puzzled by this. “Nothing is more useful than water,” Smith wrote in The Wealth of Nations, but “scarce any thing can be had in exchange for it.” A diamond has little practical value, he wrote, “but a very great quantity of other goods may frequently be had in exchange for it.” Economists have since solved the mystery, recognizing that value lies on the margin. When water is abundant, the next drops are worth little. But when it is scarce—as it is now in the West—water can be extremely valuable.

If water markets are allowed to function, prices provide incentives to conserve, and markets enable water to be moved from lower-valued to higher-valued uses. Sometimes this means transferring water rights from farms to municipalities, which can have broader economic implications for rural communities dependent on agriculture. Or it can mean finding ways to increase the economic return on water used for agriculture. In California, markets have been shifting more water to higher-revenue perennial crops, such as nuts, grapes, and fruit. Because of this, farm earnings in the state are increasing while agricultural water use is declining.

Water markets aren’t the answer to every water-scarcity problem—an “all of the above” approach is needed, including desalination, wastewater recycling, stormwater capture, and, in some places, increased storage capacity. But markets are a proven way to effectively allocate scarce resources among competing uses through voluntary negotiation instead of legal or political conflict, of which there is no shortage in the world of western water.

In the West, old rules die hard, and outdated institutions can remain stubbornly in place in the face of new realities. But the West has the need, and the ability, to adapt to an even drier future. The question is how bad the shortages will need to get in order to force those changes.