This special issue of PERC Reports features several pilot projects from PERC’s Conservation Innovation Lab. Read the full issue.

“Normally my brother would have this job,” says Lanie White. “My dad is pretty progressive like that.” Lanie returned home from a geological engineering career in 2014 to, along with her brother Harrison, help run the McFarland White Ranch, a more-than-century-year old operation that spans roughly 40,000 acres of deeded and leased land nestled against the northeastern edge of Montana’s Crazy Mountains. The nearest town is Two Dot, a census-designated place whose official population numbered 26 during the last survey.

Beyond employing his daughter as a ranch manager, Lanie’s dad, Mac, is progressive in another way: He can monitor their approximately 2,000 head of cattle on a TV screen connected to Lanie’s laptop. The ranch that dates to the late 1800s has recently adopted a cutting-edge approach to raising cattle: virtual fencing, complete with remote collars worn by every cow on the place.

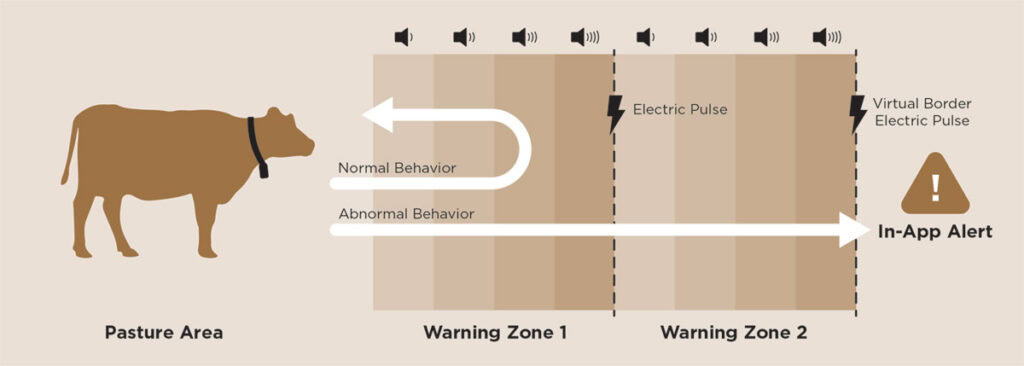

The concept is similar to invisible dog fences that were invented in the 1970s. As an animal gets close to the boundary, its collar emits a warning sound. If the animal continues on its way, and gets too close to the virtual line, the device emits an electric pulse. But while most dog virtual fences use buried wire—impractical for ranching applications for various reasons, including scale—the Whites’ virtual fences rely on a wireless radio signal transmitted across the ranch by multiple base stations. And in stark contrast to an invisible fence that operates with an immobile underground wire, the ranch’s virtual fences can be tweaked or even redrawn entirely from any place with an internet connection.

While applying the technology to cattle is a nascent endeavor, it could eventually have major implications for not just ranchers but also wildlife—much like how barbed wire transformed the West in the late 1800s. Enclosing the open range defined and secured property rights, providing untold bounty through ranching and farming. But it also yielded consequences for ecosystems and wildlife given that more than half a million miles of rural fences now subdivide the western United States. PERC and other conservation partners are supporting the McFarland White Ranch’s pilot project, aiming to demonstrate how virtual fencing can benefit ranching operations while increasing connectivity for wildlife across landscapes.

A Line in the Pasture

“If you ask agricultural producers about their biggest costs and headaches,” says Travis Brammer, director of conservation at PERC, “many would point to fence construction and maintenance.” Brammer, who was raised on a ranch in northeastern Colorado, oversees PERC’s recently launched Conservation Innovation Lab, which aims to develop and test novel approaches to address key conservation challenges. Virtual fencing technology not only has the potential to cut ranchers’ costs and increase the flexibility of their options, but it can also yield huge benefits for wildlife in the process.

“Migratory ungulates like mule deer, pronghorn, and elk get caught in traditional fences, birds can collide with wires, and ecologically sensitive areas are difficult to fence with any degree of flexibility,” Brammer says. “Physical fences are expensive to build and require nearly constant effort to maintain.” Virtual fencing can reduce the need for internal pasture fences, he says, which can help open landscapes and improve wildlife movements.

The McFarland White Ranch doesn’t just house nearly 2,000 cattle, it also harbors high-value habitat for numerous species of wildlife. About 1,000 elk winter on the property, which also hosts mule and whitetail deer, pronghorn antelope, black bears, mountain lions, wolves, and 32 bird species of concern, including long-billed curlews, sandhill cranes, and golden eagles. Lanie White estimates that the virtual fencing system will allow the ranch to eventually remove about 75 miles of interior barbed-wire fences, each with three to five strands of wire at varying heights and in varying states of repair. Physical exterior fences will remain in place to prevent cattle mingling with neighbors. “Good fences make good neighbors,” Lanie says, “and we’re a fence-out state,” referring to the legal doctrine that puts the onus on a property owner to keep others’ livestock off their land.

Virtual fencing technology not only has the potential to cut ranchers’ costs and increase the flexibility of their options, but it can also yield huge benefits for wildlife in the process.

One impetus for adopting the system was Lanie’s self-described aim to “ranch in an economically viable way that leaves the land as wild as possible.” Another was circumstance: A 2021 wildfire scorched part of the ranch, destroying fences as well as what she estimates was “several million dollars” worth of timber. Three parcels of the ranch in the foothills of the Crazies are checkerboarded with U.S. Forest Service land, preventing access by vehicle—and preventing the ranch from managing timber on the parcels. After seeking access for nearly two decades, an agreement struck with the federal agency in 2020 finally permitted the ranch to start to build 2,500 feet of roads to access the areas—but the fire got to the timber first, destroying the fences along with it.

Lanie can build and modify virtual fences from her computer—albeit with a lag for the changes to take effect—which sits next to the TV her father purchased specifically to check on the herd each morning. She can also view the location of each collar, classify cattle into different herds, get battery alerts, and even review grazing heatmap animations, which look a little like a weather radar map that displays the level of grazing pressure on an area over a given period.

She gives several specific examples of how virtual fencing will alter ranching operations. For one, it will allow her to run cattle in an area with larkspur, a plant lethal to cows if they eat just three pounds of it. It’s likely the most economically damaging plant in the western United States—the McFarland White Ranch lost about 50 cows to it the year the wildfire forced them to move cattle into an area with the poisonous plant. Because virtual fences can be finely tailored from a laptop, they will allow her to use those pastures while keeping cattle out of the larkspur, reducing ranch losses to the plant.

The technology will also make it simple to keep cows away from sensitive wildlife habitat at particular times. On a map, Lanie points to a riparian area not far from the ranch office that makes for excellent habitat for antelope fawning. Virtual fences allow her to keep cattle away from the area during the crucial period, meaning the pronghorn won’t get pushed out of prime habitat. Across the ranch more generally, she can exclude cattle from specific wetlands, streambanks, or other riparian areas when they’re sensitive to erosion, or quickly and easily move cattle out of them if they’re under too much pressure.

“We aim for four grazing treatments for our pastures in each year: heavy, moderate, light, and none,” says Lanie, who also owns the Great Alone Cattle Company, which she founded in 2017 to market beef from the ranch. The flexibility to fine tune where cattle can and can’t go will simplify management of those rotations. And while the system will benefit the ranch first and foremost, the ways it can help conserve wildlife habitat and maintain landscape connectivity has drawn plenty of interest beyond the property lines.

The ranch partnered with the National Wildlife Federation to land a grant from the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation that will offset some of the costs of collaring cattle and running the system. Each collar is rented for $36 a year, plus $10 annually for the battery, and the base stations that power the ranch-wide network cost about $12,000 apiece. Coverage depends on topography, but typically one tower can cover 10,000 acres. The McFarland White Ranch—a diverse landscape that encompasses pasturelands, creek bottoms, alpine meadows, conifer forests, and sagebrush steppe—will eventually have six towers on it. One of them, sited near Lebo Peak, was funded by PERC.

“With hundreds of thousands of miles of fences across the West,” Brammer says, “there are countless implications of virtual fence technology.” He will help Lanie assess the project’s effects on wildlife, report key findings, and search for promising opportunities to scale the approach. “PERC is excited to be partnering with the McFarland White Ranch to apply this innovative approach to ranching and, in the process, help agricultural producers and conservationists think about the implications and find ways to expand the benefits from it.”

Virtual Pressure

“Essentially what we do is put collars on cows and use sound and shock stimulus to influence where those animals spend their time on the landscape,” John Abizaid, a Denver-based business development rep for the startup Vence, said at a recent conference on wildlife migration. The company is one of several virtual fencing outfits that have come online in recent years. Founded in 2016, Vence went commercial last year and now has more than 40,000 active collars covering 1.5 million acres, mostly in the American West. The animal health division of pharmaceutical giant Merck acquired the company in 2022.

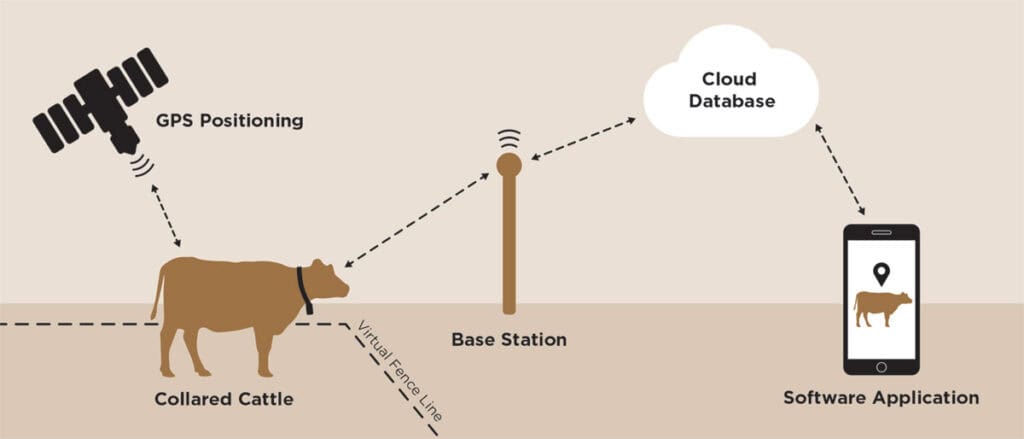

Abizaid explained the system’s three main components: collars that go on cattle, towers that create a wireless network across the ranch, and software that allows ranchers to build virtual fencelines and analyze herd data. Radio chips inside the collars transmit information between them and the towers. Each collar also houses a GPS transmitter, enabling ranchers to see the location of every device. They’re powered by batteries designed to last six to nine months depending on weather and intensity of use—how tight or loose virtual fencelines are and, therefore, how often collars emit sound and shock.

“Virtual fencing is less of a hard line in the sand where you’re in or you’re out,” Abizaid said, “and it’s more of a pressure zone for the animals.” A standard setup has a 15-yard sound zone, then a 75-yard zone that continues to deliver sound but also emits a shock. It functions as a one-way gate so that if, for instance, a cow follows its uncollared calf through a virtual fence, the cow can return to the “inclusion area” without receiving a sound or a shock. Once the cow is back inside the area, the fenceline turns back on for that animal.

The base-station towers are built for rough terrain. Their small footprint means they can be transported in a pickup truck, and they run on four batteries powered by a solar panel. A 20-foot antenna transmits a long-range radio signal, creating a low-power, low-data network across a ranch that can communicate with the collars. A cellular antenna transmits the data to the cloud so that ranch managers can access it. Vence says it has had towers running continuously through four Montana winters in places where temperatures drop to negative 40 degrees, as well as on top of mountains in Colorado with 100-mile-per-hour winds. Being able to rely on a virtual system even in extreme conditions will be crucial for the technology to have a chance at being adopted widely.

In recent years, some ranchers and conservationists have promoted modifications to barbed wire that make fences friendlier to wildlife—by using flagging, for instance, or installing a smooth top or bottom wire so that animals can go over or under without risking scrapes and cuts that can lead to infection. One recent study tracked collared mule deer in Wyoming, finding that long-distance seasonal migrations required an average of 171 fence crossings to complete a round trip.

Of course, the most friendly fence to wildlife is “no fence at all,” Andrew Jakes, Great Plains program manager at the Smithsonian Institution, noted at the recent wildlife migration conference. A wildlife biologist, Jakes has researched the impacts of fencing on wildlife and ecosystems. In one example, GPS data from pronghorn show animals migrating north to south at a fast clip, until they hit a fenceline. Then, animals spend a week or longer—and huge amounts of valuable calories, especially during cold months—just trying to negotiate a typical barbed-wire fence. “That’s just one fence,” Jakes said. “So you can imagine the potential consequences of hundreds and hundreds of fences out on the landscape.”

Transforming Rangeland, Again

“Barbed wire transformed the West,” says PERC Senior Fellow P.J. Hill, an economic historian and former Montana cattle rancher. He and fellow PERC founding member Terry Anderson documented the revolutionary effects of barbed wire in their 2004 book The Not So Wild, Wild West: Property Rights on the Frontier. Inventors filed hundreds of patents for different designs, with Joseph Glidden designing the most promising one in 1873. The production and sale of barbed wire soon skyrocketed, from 10,000 pounds in 1874 to more than 80 million pounds just six years later.

“It dramatically lowered the costs of containing cattle, sheep, and horses on one’s property,” Hill says, “and it helped transform the western range from an open-access resource into a more managed one. That allowed for proper stewarding of forage, protection of water sources, and herd improvement through selective breeding. It also, however, impeded the movement of wild game.”

Hill, who grew up ranching in eastern Montana, visited the McFarland White Ranch over the summer. He thinks virtual fencing might hold similar potential for property rights in the West. “Ranchers think long and hard about changing interior barbed-wire fences on their operations because of the costs of physical fences,” he says. “Temporary electric fences have proven to be a partial solution to the fixed nature of barbed wire, but virtual fencing drives those costs down even more.” He adds that because virtual fences spare wildlife from the effects of physical wire, there’s potential for cost-sharing agreements with conservation groups—as demonstrated by the support for the McFarland White Ranch’s transition away from barbed wire.

It generally takes less than a week to acclimate cattle to the virtual fencing system, something that Lanie White backs up. In June, she began to install the towers and collar cows, reporting that they grasped the concept within a few days. That was apparent one day later in the summer, when a group of cows being trained stood in a row about 30 yards behind a barbed-wire fence—they were assembled along a fenceline, but the fence was virtual, which left a uniform gap between the animals and the physical fence.

The same day, two wolf biologists from Montana Fish, Wildlife, and Parks stopped by to tell Lanie about their progress tracking and attempting to collar a Crazy Mountains pack that spends time on portions of the ranch. Collaring the canines would allow them to let her and neighboring ranchers know exactly when the wolves are in the area. One of the biologists weighed in with his thoughts on how virtual fencing could affect ranching on landscapes with predators. “If a rancher can look at their computer and know that a cow is dead,” he said, “they can sleep at night. If it doesn’t move locations for six hours, it’s dead, and then they can go out the next day to verify the kill and be compensated for it,” referring to the state program that pays ranchers for confirmed livestock losses due to wolves, grizzlies, and mountain lions.

More than Cows

Part of PERC’s groundbreaking elk occupancy agreement in Paradise Valley was to build over a mile of fence to keep cattle out of forage, leaving it to elk for the winter. If virtual fencing becomes deployed widely, then many ranchers will one day be able to construct such a fence remotely. Conservationists could swiftly compensate ranchers for leaving areas of forage to big game. They could craft leases that seasonally open migratory bottlenecks or eliminate strenuous fence crossings. Or they could contract to improve habitat specifically for birds or other non-game species.

These hypothetical use cases help illustrate PERC’s interest in virtual fencing and how it fits squarely within the focus of the Conservation Innovation Lab. Sure, the technology itself is novel and interesting. But ultimately, virtual fencing could revolutionize property rights on western rangelands in a way that creates opportunities for all sorts of new conservation-oriented contracts and markets. The combination of strategically removing barbed wire, monitoring cattle, and measuring the outcomes holds incredible promise. Flexible and dynamic leases could not only create new ways for conservationists to contract for particular outcomes, it could also open new streams of revenue for ranchers who soundly steward land and wildlife.

On the McFarland White Ranch, a key part of the virtual fencing pilot is to ensure that the ranch can remain financially viable while producing the ecological outcomes that benefit wildlife on the ranch and project partners off of it. In that light, piloting virtual fences seems like just another way the ranch aims to blaze new trails with its operations. As Lanie concisely puts it, “There’s more to this landscape than cows.” Once the barbed wire comes down and the ranch’s pastures open up, it will be easier to see how right she is.