This special issue of PERC Reports features several pilot projects from PERC’s Conservation Innovation Lab. Read the full issue.

Montana cattle rancher Druska Kinkie understands keenly how timing, and the cycles of nature, influence her tenure on the land. For three generations, the survival of the family ranch has depended upon it.

Every year, Kinkie and her husband stand on their property along the banks of the Yellowstone River in Paradise Valley and, in their minds, trace the path of this storied watercourse upstream more than 100 miles into the interior of Yellowstone National Park where the shimmering flows originate. They are well aware that two kinds of unstoppable floods will be coming their way. Both are connected to winter, when deep snows accumulate in the high country.

One is a torrent of rising flows that arrive in late spring as melting snow combined with June rain pushes the Yellowstone River, like clockwork, out of its banks, submerging part of their land. The second inundation is a flood of elk pouring out of the mountains to seek easier living on the floor of Paradise Valley during the snowy months of winter and early spring.

Neither can be turned back. And here, in what Kinkie calls “the hot zone,” hundreds of elk show up on the same ground, at the same time, where her cattle are calving. It’s a spot, vital to their beef operation, where cattle are fed before being turned out onto summer pasture in the mountains of the nearby Custer-Gallatin National Forest.

Outsiders passing by the Kinkie’s ranch on their way to Yellowstone might take a gander, see the elk and cattle, and believe it to be a scenic idyll of pastoral tranquility. But their windshield perspective would be a mistaken one.

While roaring water brings its own challenges, dealing with elk is existentially daunting, Kinkie says. The big-game animals transport something far more threatening to the cattle herd, and it has huge implications not only for the ranch’s financial solvency but also the pastoral way of life and appearance of Paradise Valley in the future.

“We love what we do. We love the land. We all have a desire and willingness to make changes, but we need to get through this, because otherwise we’ll all lose so much.”

— Druska Kinkie

The menace is an invisible malady, a bacterium called brucellosis, that elk carry, having contracted it from Yellowstone bison. When brucellosis infects domestic pregnant cows, it can cause them to abort their fetuses. An outbreak results in costly quarantine procedures imposed upon a ranch and has the potential to ruin an operation altogether. What Kinkie means by “hot zone” is a wildlife-livestock mixing area where the possibility of brucellosis transmission is elevated. The disease is only present in Greater Yellowstone.

“Every rancher I know is a good steward,” she says, “and if you’re not, you’re shooting yourself in the foot. I don’t want people to feel sorry for us. There’s a big difference between that and empathy. We love what we do. We love the land. We all have a desire and willingness to make changes, but we need to get through this, because otherwise we’ll all lose so much.”

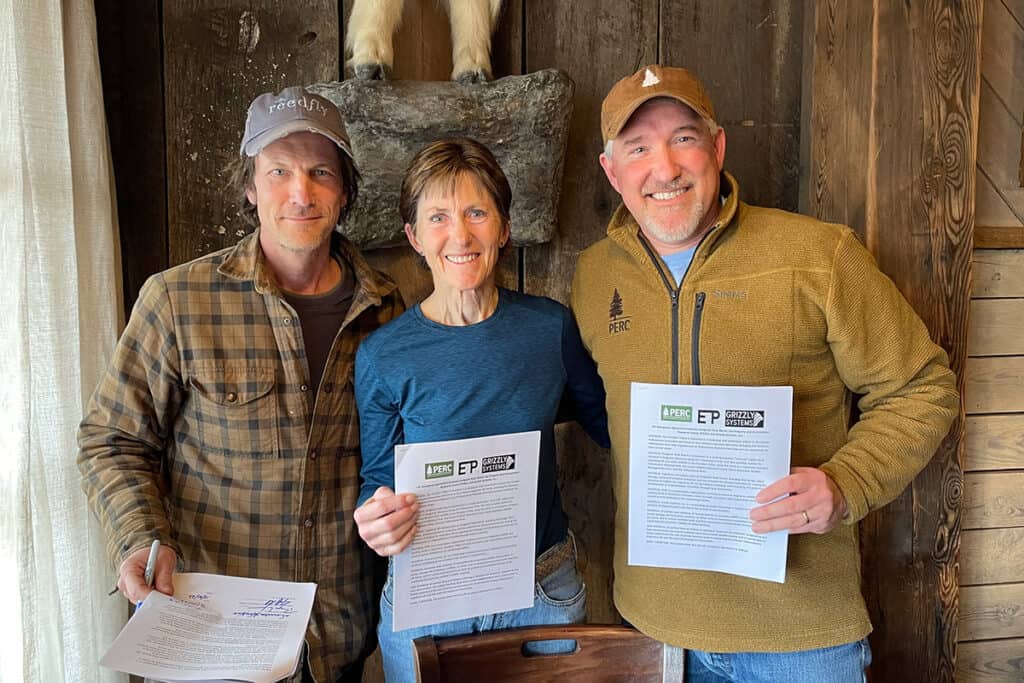

What can be done? In recent years, PERC and a cohort of landowners, conservation groups, and citizens have advanced two pioneering market-based initiatives. One of them, incubated by PERC staff and fellows in its Conservation Innovation Lab, is the creation of a brucellosis compensation fund designed to help cover the costs associated with a potential quarantine event. Another is the invention of elk occupancy agreements that pay ranchers to allow elk to use or move across their land.

A third pilot effort focuses on helping ranchers like the Kinkies lighten the load of what they consider to be an “elk burden.” The so-called “pay for presence” project compensates the ranch for images of elk captured by remote cameras, rewarding the Kinkies for the critical habitat they provide to the migratory herds. The effort completes a trifecta of common sense, incentive-based solutions that PERC is piloting to mitigate elk-livestock conflicts.

Calculating Elk Rent

The effectiveness of any promising idea, no matter how innovative, rests on its ability to be measured, replicated, and potentially scaled. For a pay-for-presence project to prove its return on investment, PERC enlisted the services of Paradise Valley native Jeff Reed. Several years ago, Reed returned to his home dell after finding success as an IT programming expert in Silicon Valley.

Concerned about the future of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, its famous wildlife, and rural character as exemplified by its ranchers and farmers, Reed founded Grizzly Systems to apply tools like artificial intelligence and scientific monitoring techniques such as camera traps to issues in the region. Today, he’s putting his know-how to work on PERC’s pay-for-presence initiative.

“For many ranchers in this valley and others,” Reed says, “elk are viewed not as benign creatures, but as predators. They eat grass that might otherwise go into the bellies of their cows. They damage fences, demand vigilant attention, and carry disease. I can tell you that Druska isn’t waking up in the morning and most worried about running into a grizzly or wolf. She’s worried about elk.”

It certainly doesn’t hurt that, geographically, Reed lives just across the Yellowstone River from the Kinkies’ pastures. He also serves as a citizen volunteer, along with Kinkie, on the Upper Yellowstone River Watershed Group, which brings together a wide range of stakeholders to address local watershed issues.

“What attracted me to this collaboration is its simplicity in giving ranchers relief and the potential it has to help keep these landscapes protected,” Reed says. “You monitor to detect presence of elk and pay the rancher based on the number recorded with a camera. The added money they receive helps to subsidize the cost of them being there and rewards ranchers for providing a public benefit.”

By deploying cameras in strategic locations and using AI face- and body-recognition advancements, Reed is experimenting with a method to identify when and how many different individual elk occupy the Kinkies’ pastures. In addition to helping calculate payments for “elk rent,” a major benefit is that the Kinkies gain a broader glimpse of what’s happening at all hours of the day. That informational benefit will also appeal to other ranchers who may partake in the program in the future.

“Druska isn’t waking up in the morning and most worried about running into a grizzly or wolf. She’s worried about elk.”

— Jeff Reed

“This allows landowners who are constantly on the run to gain a bigger, wholer picture,” Reed says. “We are keeping a visual log of all creatures, not just elk,” he adds, noting that on the Kinkie’s ranch, cameras have documented the presence of pronghorn—rare on the east side of the Yellowstone River—all the way down to smaller fauna like porcupines and jackrabbits.

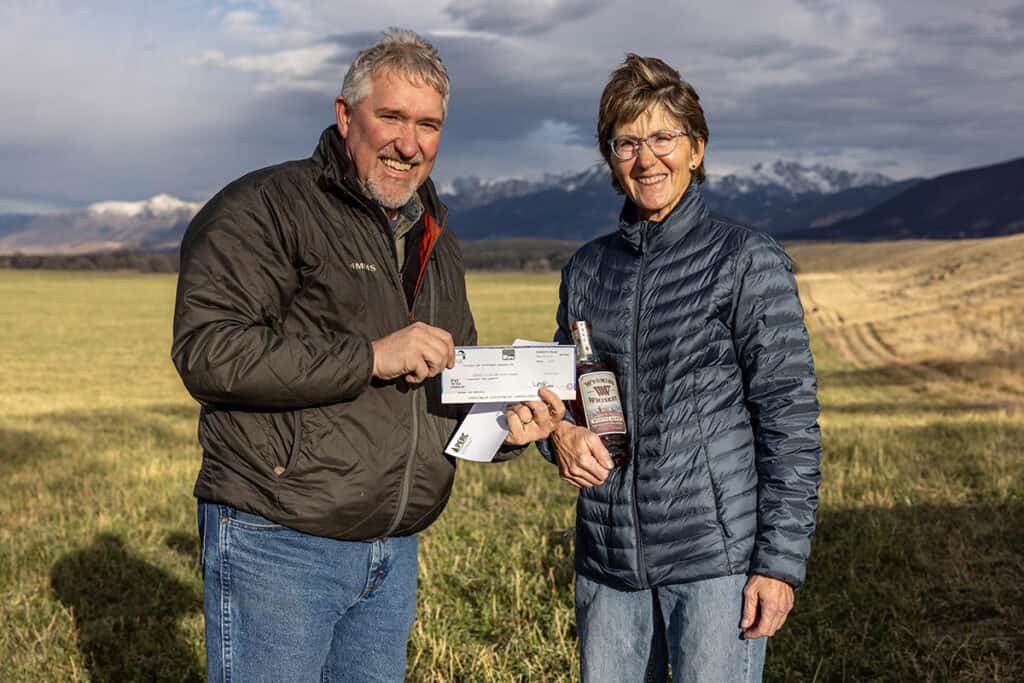

Calculating elk rent under the agreement is fairly straightforward. A minimum of 20 elk captured on camera in a single day constitutes an “elk day” and triggers a financial payout to the rancher. A bonus payment is offered when 200 or more elk are captured in a single day, with a $12,000 cap on total annual payments.

The pilot project is designed to test the formula and assess how well the AI game cameras “learn” how to identify elk. Smartphone photos taken directly by the Kinkies can also augment the cameras and contribute to the visual log.

Between a Herd and a Hard Place

Just like property owners trying to stay above flood waters, ranchers do everything they can to stay out of the red. Whether it’s dealing with blizzards and drought, suffering animal illness, trying to put up two crops of hay when weather accommodates, striving for better efficiency in raising cattle and getting animals to market, or keeping maintenance and operational costs down, they are caught in a constant squeeze to make ends meet.

On top of it, Kinkie says with a touch of melancholy in her voice, many ranchers and farmers in Paradise Valley and the wider West are aging out, and their children don’t want to continue the ranching traditions of their ancestors. Many offspring are willing to sell the ranch. In Montana, it has set off one of the most head-spinning land-use transformations since statehood was achieved in 1889.

“It touches us all in our hearts,” Kinkie says. “When you lose your neighbor and their place to a subdivision populated by outsiders who have no deep personal connections to each other and the land, you lose a sense of community and belonging that, once it’s gone, you can’t bring back.”

Of course, forces besides demographic and economic change affect how the land in this valley will be used in the future. Kinkie notes that a single brucellosis outbreak and accompanying quarantine of her herd would deliver a potential knock-out blow to the ranch’s bottom line. Quarantine entails animals being locked down in isolation until a herd is deemed to be clear of infection. In some cases it can even result in total eradication of a herd. At the very least, it involves prohibitions on moving animals or selling them at market, and it brings the added expense of having to feed hay to confined animals, sometimes for up to a year. According to a 2016 analysis, a cow-calf operation with 400 animals could incur $150,000 in direct quarantine expenses.

Keeping this landscape together and economically viable to ranchers is critical to providing elk wintering grounds at a time when the animals most need it.

Genetic tests trace almost all brucellosis outbreaks to elk, which is why those animals—more so than large carnivores—keep ranchers like the Kinkies up at night. Thousands of elk from the Yellowstone Northern Herd migrate out of the national park at the start of winter, eventually reaching parts of Paradise Valley where the Kinkies keep their cattle.

Over the years, the Kinkies and their ranchhands have tried many different forms of hazing to move elk away from their cattle but often to no avail. Kinkie will never forget the late spring evening she returned from a school board meeting and saw hundreds of elk that had moved into her pasture, standing side by side with her cows and calves. “That night I cried,” she says, “expecting the worst.”

Fortunately, no brucellosis transmitted from elk to cattle that night, but it was a jarring reminder of how difficult coexistence can be. There have been three livestock quarantine events linked to brucellosis-infected elk in Paradise Valley alone over the past decade. “Knock on wood, we’ve somehow managed to dodge the bullet,” Kinkie says, “but for how long we don’t know.”

Opportunity in Paradise

With a situation long thought intractable and looming, the opportunity was ripe to try something new. Human behavior, as has been shown time and again, is influenced mightily by economic signals, says Brian Yablonski, PERC’s chief executive officer. He believes that finding ways for wildlife to be viewed more as an asset than a liability opens the door to creative problem solving that yields better results for both the private property owners who provide wildlife habitat and the animals that need it.

Yablonski first met Kinkie five years ago at the Old Saloon in Emigrant, not far from her ranch. He knew the brucellosis issue was contentious and complicated—a political and policy quagmire. “Druska and I sat and drank coffee for a few hours together,” he says. “It was a heartfelt and sometimes emotional meeting about the struggles ranchers were facing due to elk using the valley as winter range. And it was at that moment that the Paradise Valley work we would soon embark upon became ‘real’ for me and something of a personal mission.”

Paradise Valley commands a prominent profile in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem and potentially holds lessons for other high-growth areas where development pressure, ranching, and wildlife are on a collision course. Most of the valley floor is private ground, with open space and critical wildlife habitat found in a mosaic of a few dozen family-operated cattle producers, some of whom barely eke out a living. Some 80 percent of the species in Greater Yellowstone rely on habitat found on these private land. When ranchers face economic challenges that seem insurmountable, they may sell to the highest bidder. In recent years, some of those buyers have been developers who replace cows with condos. If that happens, wildlife can become displaced.

Spending time with experts like Arthur Middleton, a U.C. Berkeley ecologist who has been at the forefront of tracking—and mapping—movements of elk, mule deer, and pronghorn in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, Yablonski has come to realize a sense of urgency with growing development pressure. “What’s become clear to big-picture thinkers like Arthur Middleton, we at PERC, and other conservation partner organizations,” Yablonski says, “is the importance of private lands for elk. But often, because of conflict, they’re viewed as uninvited guests. Keeping this landscape together and economically viable to ranchers is critical to providing elk wintering grounds at a time when the animals most need it.”

According to Kinkie, however, so many different organizations have tried to help but failed to deliver. “For a long time,” she says, “many of us in this valley felt like we were confronting these challenges alone, and people in the conservation community either weren’t interested or didn’t want to listen to our fears and concerns. But with PERC, groups like the Greater Yellowstone Coalition, and others associated with the Upper Yellowstone Watershed Group helping us address these concerns by providing funding, we feel like we have real allies.”

“If we could help Paradise Valley landowners like Druska with the impacts of elk, we would not only be helping ranchers but helping elk and other wildlife.”

— Brian Yablonski

“I gave her my word,” Yablonski says. “If we could help Paradise Valley landowners like Druska with the impacts of elk, we would not only be helping ranchers but helping elk and other wildlife. She has been our rock throughout and the one who has opened doors so that this could become a valley-wide effort.”

The good news, he says, is that citizens who cherish the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem are coming to appreciate the importance of unfragmented wildlife migrations. “People are moving in droves to places like Bozeman for our outdoor amenities and assets,” Yablonski explains. “That is, by definition, a market.” He points out that PERC’s motivation is to put more market-based incentives in the conservation toolkit so that results can be delivered faster.

“People want to express their values and bring their own resources to bear,” he adds. “PERC’s role has been to channel that emerging market to actions and projects that really make a difference. In the past, that enthusiasm has been diverted to regulations or legislation. But wouldn’t it be great if we could put that market to work directly on the ground in a way that is more nimble, responsive, and speedier than clunky government programs?”

Rays of Hope

The payment for presence concept has gained traction in several other contexts. A few years ago, the nonprofit American Prairie launched a program that pays ranchers in central Montana a premium for implementing wildlife-friendly practices. Part of the initiative rewards ranchers with cash payouts when they document rare species such as grizzly bears and wolves using camera traps. A similar program has been employed by the Northern Jaguar Project in northern Mexico. There, elusive and rare jaguars are protected on a preserve, yet the big cats often wander. The project compensates participating adjacent ranchers who install cameras and agree not to hunt, poison, bait, trap, or disturb jaguars and their prey species—deer and javelina. Ranchers receive monetary awards whenever they capture photographs of the wild cats, demonstrating proof of presence.

In Paradise Valley, Yablonski says there is no “magic bullet” available to completely give ranchers peace of mind, but the three pilot projects PERC is pursuing are, as Kinkie calls them, rays of hope. The AI camera-trap technology is on the cutting-edge, but it’s still being refined. As the system evolves, so too can the model of this program, delivering more refined and tailored results for ranchers.

“We are in something of a race to give ranchers better options so they can stay on the land,” Yablonski says. “Development pressures are enormous. All the ranchers I’ve met want to remain being ranchers. We have to make it worthwhile for them. The open space and wildlife habitat doesn’t pay for itself. The more tools we can provide, the more reasons we can give them to stay on the land and show that private landowners are conservation heroes, whether they see themselves that way or not.”