Starting January 1, 2026, overseas visitors who pull up to the gates of 11 of the most popular U.S. national parks (including destinations like Yellowstone, Yosemite, and the Grand Canyon) will pay a $100 surcharge on top of the base entrance fee. The price of non-resident “America the Beautiful” annual passes will also rise, to $250, while remaining $80 for Americans.

The policy change is fantastic news for anyone who cares about national parks, including visitors from abroad.

For years, PERC has argued that higher fees for non-resident visitors are one of the smartest, fairest ways to protect America’s best idea at a time when our most famous parks are straining under record crowds and aging infrastructure. Earlier this year, we met with Interior Secretary Doug Burgum to share this idea.

Here are six reasons why the new international visitor surcharge is a win for the parks and for everyone who loves them.

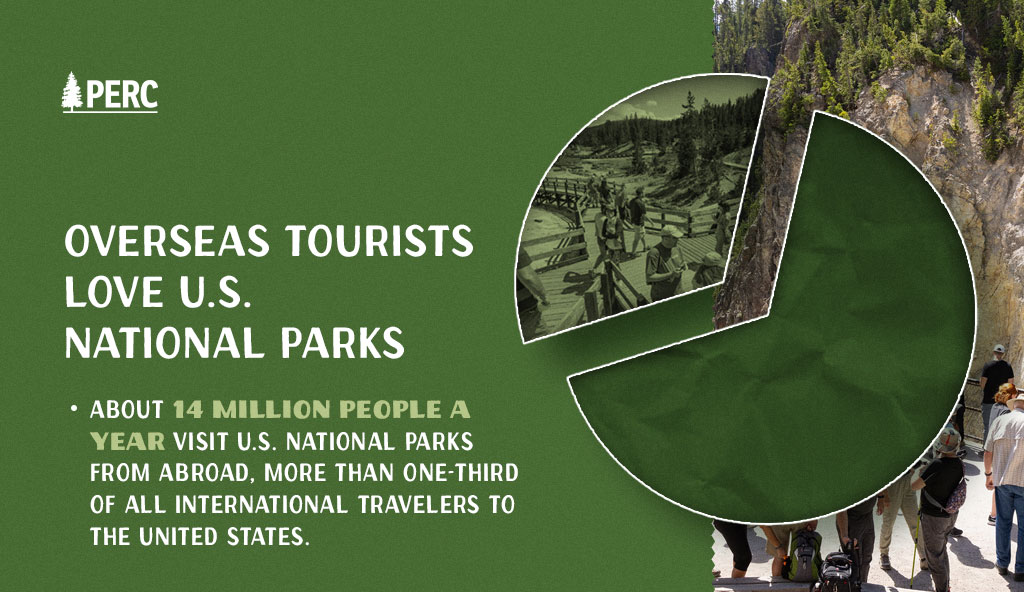

1. Because overseas visitors really, really love U.S. national parks

If you’ve ever been in line for coffee at Old Faithful or on a shuttle bus at Zion and heard a chorus of different languages, you’ve seen this first-hand.

- At Yellowstone, new PERC research shows that roughly 600,000–700,000 visitors each year come from other countries, about 15 percent of total visitation to the world’s first national park.

- At Grand Canyon, an estimated 30 to 40 percent of visitors are international travelers, or roughly one-and-a-half million of the park’s nearly five million total visitors each year.

Zoom out from any single park, and the numbers get even bigger. About 14 million people a year visit U.S. national park sites from abroad, more than one-third of all international travelers to the United States.

Those travelers don’t just bring their cameras: They fill hotels, restaurants, and guide services in gateway communities, supporting thousands of local jobs while they take in world-class natural wonders.

And the evidence is clear: A higher entry fee doesn’t scare them away.

A recent PERC economic analysis for Yellowstone finds that demand from overseas visitors is extremely inelastic. A 10 percent increase in entry fees would reduce international visitation by an estimated 0.03 percent—effectively a rounding error.

Why? Because the fee is a tiny slice of the total trip cost. The average overseas visitor to Yellowstone spends about $4,500 on their trip; a $100 fee hardly moves the needle.

2. Because parks urgently need the help

Here’s the uncomfortable reality behind all of those Instagrammable vistas: the infrastructure holding up our awe is falling apart.

- Nationwide, the National Park Service faces an estimated $22 billion deferred maintenance backlog.

- Yellowstone alone has about $1.5 billion in overdue maintenance, the largest backlog of any park.

That backlog isn’t abstract. It shows up as overflowing restrooms, failing wastewater systems, eroded trails, crumbling boardwalks, pothole-ridden roads, aging bridges, and dilapidated employee housing that makes it harder to recruit rangers and staff.

Congress gave parks a vital, but temporary, boost with the Great American Outdoors Act’s Legacy Restoration Fund. But that money mainly tackles the most urgent repairs; it doesn’t solve the ongoing mismatch between soaring visitation and flat, inflation-eroded appropriations.

In short: Awe has an upkeep cost, and right now we’re not keeping up.

3. Because we can turn love into real money for parks

This is where the new surcharge shines. It taps a visitor group that’s both enthusiastic about parks and financially able to help steward them.

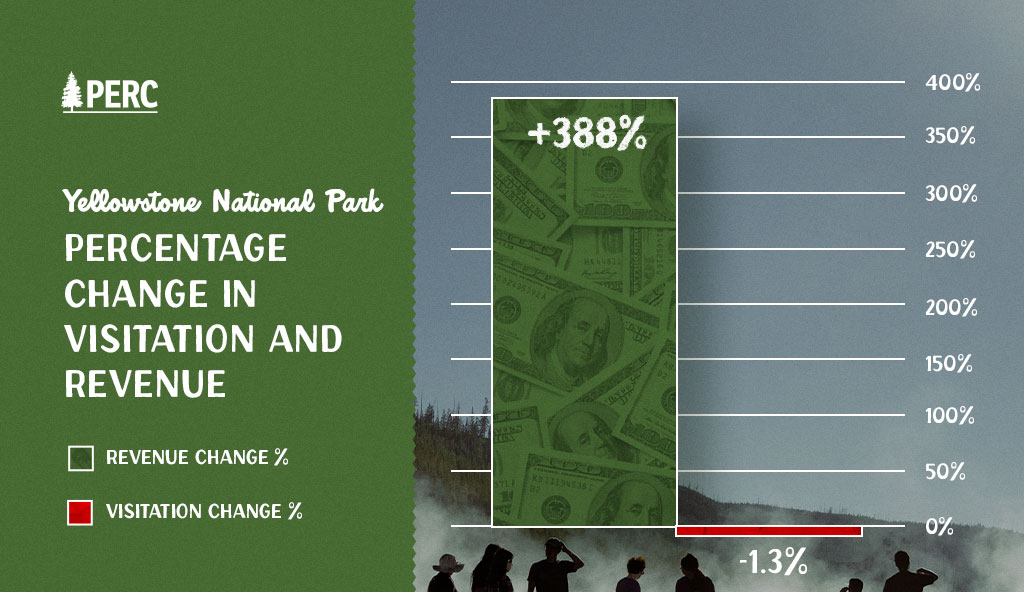

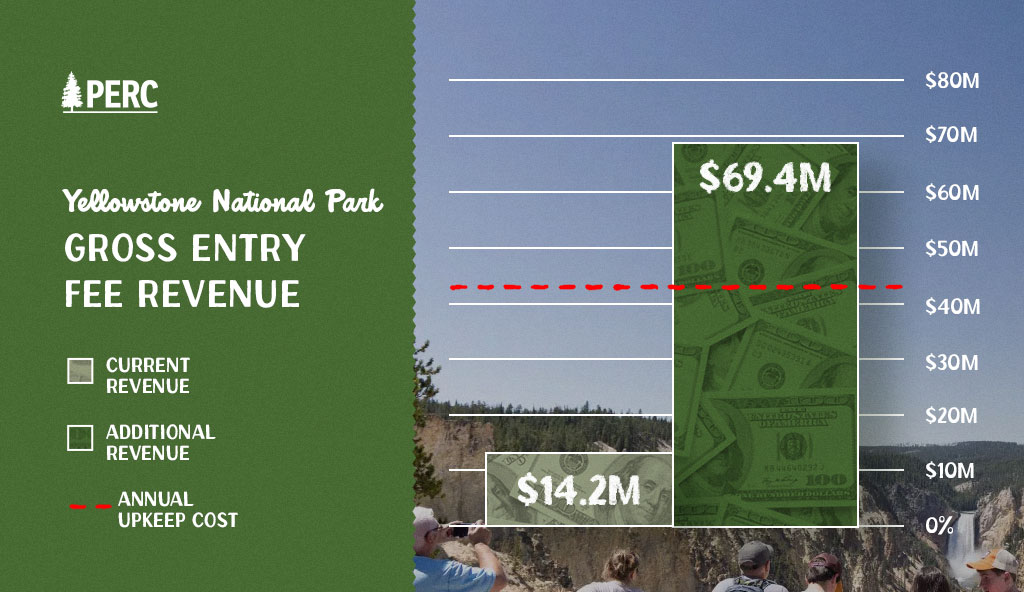

PERC’s latest modeling for Yellowstone shows what a $100 international surcharge can do:

- A $100 surcharge per overseas visitor would generate an estimated $55.2 million in additional revenue each year at Yellowstone alone, almost four times the park’s current entry-fee revenue.

- Projections show that extra money would come without significantly impacting attendance, yielding an estimated 1.3 percent decline in total visitation, entirely from overseas visitors.

What does $55 million actually buy?

Yellowstone estimates it needs about $43 million a year just for routine maintenance and everyday work that keeps the park functioning. With revenue from the surcharge, Yellowstone could hypothetically:

- Cover all annual upkeep costs

- Demolish the abandoned wastewater system at Old Faithful (about $6 million)

- Make much-needed improvements at the Midway Geyser Basin (around $5 million)

Crucially, this money is designed to stay in the parks:

Under the Federal Lands Recreation Enhancement Act (FLREA), 80 percent of entrance-fee revenue must remain at the park where it’s collected, to be spent on maintenance, visitor services, staffing, and capital projects. (And the remaining 20 percent of revenue stays within the system to support other national park sites.)

That creates a powerful feedback loop: Parks that welcome visitors well and invest in great experiences earn more resources to keep doing exactly that.

4. Because it helps keep politics out of parks

In theory, Congress could simply appropriate more money every year and call it good. In practice, that’s not how things work.

Park budgets are subject to ever-shifting political winds. As administrations and congressional majorities change, appropriations lurch up and down, making it hard for superintendents to plan beyond a year or two at a time. That’s not practical given the size and complexity of these destinations.

When there’s a government shutdown, parks become bargaining chips, whipsawing staff, gateway communities, and visitors.

Entrance and surcharge revenues are different:

- They’re paid by the people actually using the parks, ensuring they are often more durable and stable than lines on a budget in Congress.

- They’re highly predictable and tied directly to visitation, which has been remarkably steady at around 300 to 330 million recreation visits per year system-wide.

- They’re locally controlled: Superintendents and on-the-ground staff can spend free revenues without further appropriation from Washington, D.C., meaning they decide which trails to fix, which bathrooms to upgrade, and which bridges to repair.

That local control matters. A superintendent facing a failing wastewater system at Grand Canyon or a dangerous bridge at Yosemite can’t wait for the next budget cycle drama on Capitol Hill. A robust, user-supported funding stream gives them the ability to act.

Think of the surcharge as a stability tool: It smooths out the political roller coaster so park staff can make long-term, boring-but-essential decisions—exactly the kind of decisions that keep your favorite overlook open, accessible, and safe.

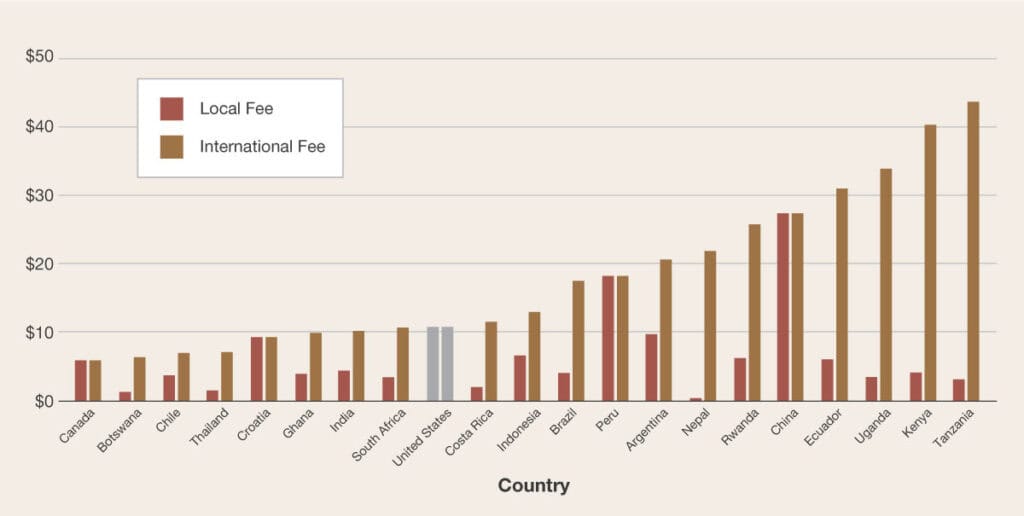

5. Because the U.S. is simply catching up with the rest of the world

If you’ve traveled to other bucket-list destinations, you’ve probably already experienced international surcharges. This is common practice abroad. Our global benchmarking study finds dozens of national park systems around the world charge non-citizens more than citizens, often by large margins:

- Torres del Paine, Chile: roughly $55 for foreign visitors vs. about $14 for Chileans on multi-day passes

- Galapagos National Park, Ecuador: $200 for foreign tourists, $30 for Ecuadorians

- Kruger National Park, South Africa: about $25 per day for international visitors, $6 for locals

And it’s not just an international thing. Inside the U.S.:

- Manystate parks charge higher entry or camping fees to out-of-state visitors, often $10 more per night or more for campsites.

- State wildlife agencies routinely charge non-residents much higher fees for hunting and fishing licenses; for example, an out-of-state elk hunter in Montana can pay more than $1,200 in licenses and permits vs. under $50 for a resident.

When an American visits the Galapagos or a neighboring state park, we’re already used to paying more because we’re not part of the local tax base. We’re also happy to pay, knowing we’re helping care for a global treasure.

The new surcharge simply applies that same logic: Americans keep affordable access to their own parks, while international visitors chip in a little more for the privilege of visiting.

6. Because it’s a long-term investment in awe

Right now, international tourism is being impacted by geopolitics, exchange rates, and the global economy. That’s showing up in visitor numbers to the U.S. in ways that have nothing to do with park policy.

But PERC’s research is clear: reasonable surcharges would not be the driver of any downturn. They have minimal effects on visitation, especially among international travelers.

What will determine whether future generations, American and international, can stand on the rim of the Grand Canyon or watch Old Faithful erupt is whether we invest in safe roads and bridges, modern water systems, well-maintained trails, and adequate visitor amenities.

That’s exactly what the new surcharge helps pay for.

For an overseas traveler already spending thousands of dollars to cross an ocean, a $100 contribution to protect the geysers, canyons, and wildlife they came to see is a rounding error, and a meaningful act of stewardship.

By asking those who travel the farthest, and often spend the most, to chip in a bit more, the U.S. is aligning park funding with park use, while keeping parks welcoming and affordable for all visitors.

National parks are a gift to the world. They’re also a responsibility. The new international visitor surcharge is not about closing the gates to global tourists; it’s about keeping them open, safe, and awe-inspiring for everyone.

That’s something park lovers from every country can get behind.