After years of heightened inflation and sky-high housing and energy costs, one concept pervades American politics and culture today: the “affordability crisis.” The median age for a first-time home-buyer has climbed to an all-time high of 40 years old. Heating costs have risen by roughly 30 percent over recent years. Electricity costs are up, and rising numbers of Americans are facing debt collection over unpaid utility bills.

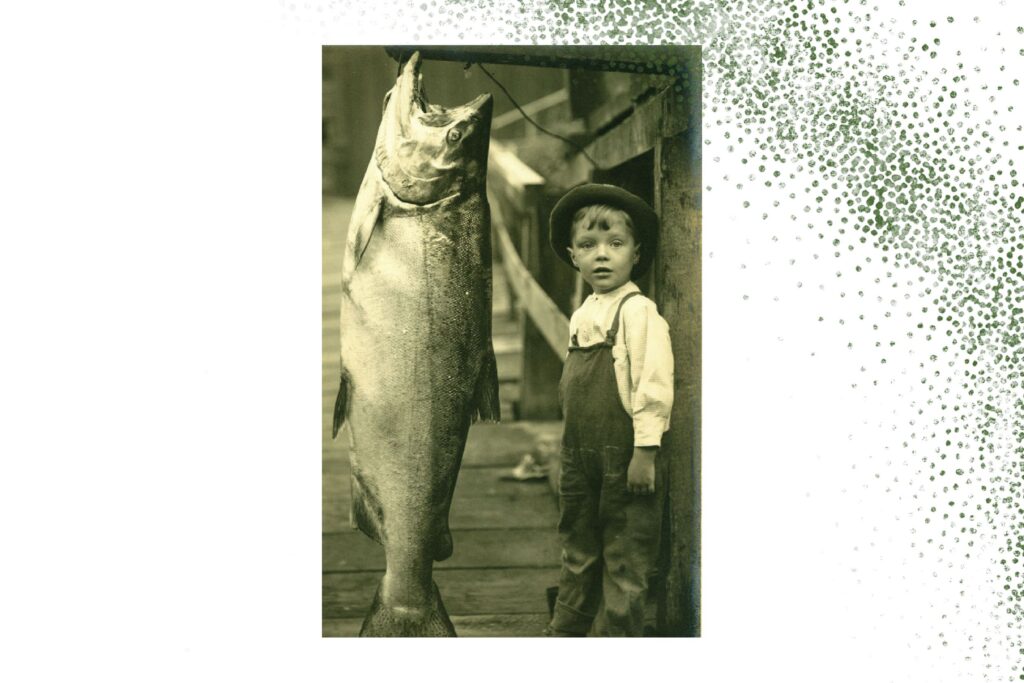

Affordability arguably sealed the outcome of the 2024 presidential election and seems to have influenced ballot-box results in November as well. But while I believe meeting human needs like houses and energy is critical, when I think about the need to provide more in the world, I also can’t help but think about fish—enormous fish.

At the heart of the affordability crisis is scarcity of built infrastructure, including housing, electricity transmission lines, and transit. There simply aren’t enough of the things that people need, so prices rise, encouraging supply to catch up to demand. But like infrastructure itself, much of the scarcity is manmade, created by a system of laws, policies, and norms that make it easy to slow or stop projects, and dampen the supply response of markets.

Likewise, a host of conservation challenges are also underpinned by scarcity. Only a century ago, for example, schools of Chinook salmon bigger than golden retrievers swam up the Columbia River. Somewhere between 10 and 16 million salmon and steelhead spawned in the Columbia Basin each year. Then, once dozens of dams were built along the Columbia and Snake Rivers for hydroelectric power—compounding overharvesting and habitat degradation from growing timber and agriculture industries—salmon populations crashed, and their size also dwindled. Today, just one to two million salmon and steelhead return to the Columbia annually, and hundred-pound salmon are unheard of. While economic analysis suggests net benefits would result from removing dams, concerns about reduced energy supplies and other costs of removal have repeatedly stalled action.

The opposite of scarcity is abundance—a topic that is top of mind in political and policy circles today. As Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson argue in their 2025 bestseller, Abundance, we can solve our problems of scarcity and build plentiful infrastructure by reforming land-use regulations, overhauling permitting processes, inventing new solutions, and harnessing other supply-boosting approaches. A growing, bipartisan abundance movement is gaining popularity, increasingly translated into real political power.

Many conservation challenges share similarly powerful “abundance” solutions with the affordability crisis. Much of the world’s “natural infrastructure”—the functioning ecosystems that provide clean water and air, fish and wildlife habitat, recreation opportunities, livestock forage, wood products, carbon storage, and more—is in need of rehabilitation. But as in the built world, our slow political and policy systems bog down projects that aim to rebuild or improve natural infrastructure—sometimes, they even favor constructing with concrete or steel over restoring forests or rivers. To take one example, a California project to restore riparian habitat needs more permits than an Alaskan oil pipeline. But that can change.

Traditionally, conservation strategies and tools have focused on a principle aim: reducing harm. And this approach has achieved much success by defending protected areas, regulating hunting, and guarding against habitat destruction. Spectacular national parks and massive rebounds of wild turkeys, white-tailed deer, and many other game species stand as testaments. But these defensive tools are not enough, as the ongoing global decline in habitat and biodiversity shows.

Conservation groups may see the abundance movement as a threat, because they fear giving up defensive regulatory tools as well as a massive loss of habitat to infrastructure. The risk is real. In the United States alone, over 30 million acres—more than 10 Yellowstone National Park’s worth—of natural areas and farmland could be converted into housing by 2040. The U.S. is expected to add 250,000 to 500,000 acres of new solar power generation, equivalent to roughly a Grand Teton National Park’s worth, per year between now and 2030. And this is not just a domestic problem. Globally, the amount of infrastructure is expected to double by 2030, transforming our planet.

The question facing our country and the world more broadly is not whether a massive amount of energy infrastructure and housing will be built, but where, how and when. And those are questions that conservationists can and should help answer. If conservation values and research can be included in siting, designing, and building more of what people need, then both nature and people will win.

By the same token, adopting an “abundance mindset” to tackle conservation challenges can help restore natural abundance in surprising ways. Here are five key principles that can help unlock the potential of abundance for humans and nature:

Dream big to restore habitat and species

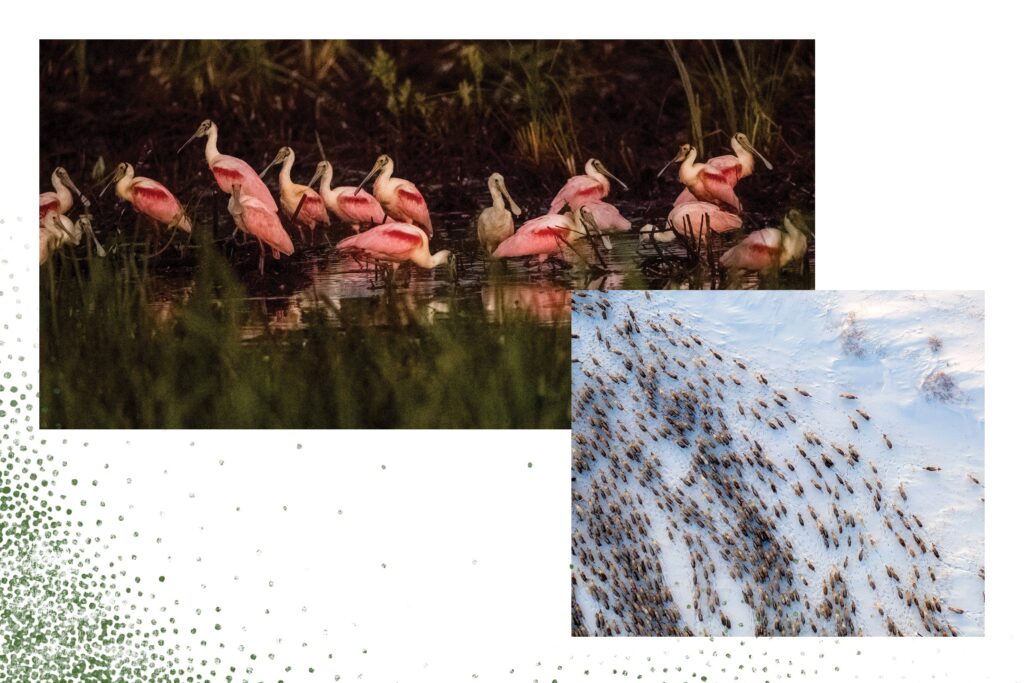

In the Tongass National Forest in Southeast Alaska, salmon are still so plentiful that they fill creeks in late summer with a shining, rippling mass of fish. After spawning, the nutrients from the bodies of those salmon feed the entire ecosystem, growing massive riparian trees and a rich understory of plants, which in turn feed countless insects and birds. Wolves, bears, eagles, and many more creatures feed on those salmon directly. It’s an example of nature’s super-abundance, but it’s increasingly rare.

What if we could recover natural abundance elsewhere, and do so in ways that harness rather than impede the infrastructure abundance movement? Energy abundance for humans is an invitation to dream big for conservation. The return of plentiful, hundred-pound salmon to the Columbia River is possible if hydroelectric dams can be replaced by new sources of abundant energy. The Klamath River offers an example of what is possible. In 2024, a century after the construction of four major dams excluded salmon from the upper Klamath, the largest dam removal in U.S. history brought them down. The negotiations and eventual agreement and legislation needed to remove the dams took 14 years, following decades of conflict, and the permitting, demolition, and restoration took another four years. But just a day after the last dam debris was removed in October 2024, a salmon was detected swimming past the demolition site. A year later, Chinook salmon have returned over 300 miles upriver to spawn far upstream of the former dam sites, faster than biologists can keep up with monitoring. Recovery of natural abundance can be rapid, if we can get past the human choices and construction processes that are blocking it.

Include people and livelihoods in conservation

Durable conservation solutions must work for people, too, and we should create and seize opportunities to make more of these “win-wins” happen. In the western United States, if cheap energy can make and move more water where it is needed, then we might find peaceful resolutions to the “water wars.” The Colorado River, for example, has seen roughly 13 percent declines in supply of water in the past quarter-century due to a warmer, drier ecosystem, while overall consumption has held steady. Advances in desalination have the potential to boost the supply of drinking water for coastal cities, or even for inland areas with sufficient pipeline infrastructure. Fifty years ago, it took more than six times as much energy to desalinate seawater, and the technology continues to improve rapidly. Now, desalinating enough water for an average American household would take about half the energy that family uses for air conditioning. With abundant, cheap energy, the scenario goes from daunting to doable.

Increase incentives to build and maintain natural infrastructure

We desperately need to increase the supply of high-quality habitat, which remains the primary threat for most declining species worldwide. There are a growing number of proven, incentive-based tools to boost the supply of wildlife habitat, like paying ranchers for elk presence to reduce the costs of coexistence, compensating farmers to leave water in streams for trout, and sharing costs with ranchers to improve sage grouse habitat. But to unleash the power of incentives for conservation abundance, we need to increase financing in creative ways, as well as make changes to law and policy, such as reforming aspects of the Endangered Species Act to give landowners an incentive to recover listed species on their land, as PERC has long advocated.

Reduce barriers to active conservation

The wildfire crisis costs Americans nearly $400 billion annually and threatens ecosystems and human communities alike. Forest management, such as thinning and prescribed burning treatments, can greatly reduce wildfire risk. But these treatments are slow, expensive, and easily stopped by local objectors and the threat and reality of lawsuits. Abundance policies could change that. For example, PERC research has found that from the time the U.S. Forest Service begins the environmental review process under the National Environmental Policy Act, it takes an average of another three-plus years to start a mechanical treatment project on the ground, or nearly five years to start a prescribed burn. More complex forest restoration projects can take much longer. Policy reforms could help accelerate solutions to the wildfire crisis—and there’s similar potential to harness reforms to speed up conservation of endangered species, movement of water through markets, and other domains.

Build conservation fixes into infrastructure abundance

Energy, housing, and other needed human infrastructure can be built in ways that maximize conservation potential—if conservation researchers and practitioners can invent and include these innovations in the construction process. For instance, building out solar on rooftops rather than in native grasslands or forests spares nature, but red tape often makes the former cost prohibitive. Dreaming up ways for solar panels to share land with farms, ranches, canals, and habitat restoration projects can not only use less land but also can juice farm profitability, reduce water loss, and build new habitat for pollinators and other wildlife. On the housing side, wins for people and the environment are possible with clustered development that avoids prime habitat, dense and intensive housing buildouts, and nature-friendly yard practices. We need to create better designs, improved siting tools, supportive policies, and sound incentives to make this happen.

Like salmon swimming upstream to spawn, there will be swift currents to navigate and waterfalls to overcome to make a conservation abundance agenda a reality. But in harnessing the principles of abundance, the conservation community, groups focused on human needs and built infrastructure, and conservation-minded citizens across the political spectrum can come together to help build a world where both nature and humans flourish.

Sophie Gilbert thanks Max Lambert, director of science for the Nature Conservancy in Washington State, for indispensable help thinking through and working on this issue. Their journal article, “Building Plentiful Housing and Energy Needs Conservation Science,” is currently undergoing peer review.