The first time I met Leigh Perkins was in 2009 at Mays Pond, his hunting lodge. Nestled among the piney woods in North Florida, Mays Pond was exactly that—a humble lodge, inconspicuous, like its owner, in a region known for its plantation manors and estates. When we met that January morning to hunt quail, he offered me a cup of coffee and then proceeded to make the cowboy version of it using a soup pot on his kitchen stove. It was something you might expect from someone whose first job, I later learned, was as a rod man on a survey crew in the iron mines of Northern Minnesota.

In 1965, Leigh purchased the Orvis Company, a 109-year-old fishing rod manufacturer with only 20 employees. By the time he retired, Leigh had transformed Orvis—and fishing itself—into an outdoor lifestyle, an ethos of appreciation for nature more than any one product, with 700 employees and sales topping $90 million. As important, if not more so, he was the pioneer of corporate conservation. Orvis gave 5 percent of its profits to environmental causes, paving the way for outdoor recreation philanthropic giants like Bass Pro Shops and Patagonia. Leigh was generous with his time too, serving on the boards of conservation organizations, including the Nature Conservancy, Tall Timbers, Trout Unlimited, and, of course, PERC.

Leigh was PERC’s longest-serving board member, joining the board in 1984 and continuing with only brief interruptions for the next 30 years. He was the anchor of a tradition of fishing legends on the board (the others being John Bailey of Dan Bailey’s Fly Shop in Livingston, Montana, and our current board member K.C. Walsh, the owner of Simms Fishing).

His indelible mark spanned nearly the entire 40-year history of PERC. Leigh was there at every critical juncture, a visionary who saw what many others might not. In PERC’s infancy, having the CEO of Orvis as part of leadership provided the organization and free market environmentalism with much-needed credibility in the conservation community. It’s also how, more than three decades later, I ended up at the helm of PERC—through Leigh’s unwavering faith and encouragement in elevating PERC’s research from journals and books into real-world conservation policy and practice, a vision he inspired until his last days on the board.

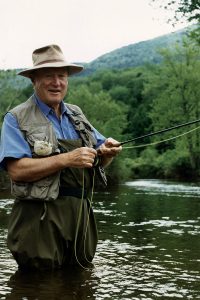

Happy go lucky, generous, humble, and oftentimes a character, Leigh was unmatched in his outdoor prowess. I remember watching him effortlessly, almost nonchalantly, cast a flyline 70 feet across a spring-fed pond in Wyoming’s Star Valley. Until the end, he hunted birds with a 20-gauge Winchester Model 21, given to him by his father when he was 16 years old. It was the gun he would let me use on my cross-country visits to hunt with him in Florida. To me, it was like holding King Arthur’s Excalibur. In the field with Leigh in his 80s, I witnessed him take impossibly long shots at speedy quail and turn to walk back to the wagon as if he missed, not realizing that his strong wingshooting instincts still resulted in a downed bird.

Leigh was a dog man first and foremost. Having had the privilege to quail hunt many other properties in the Red Hills region of Florida and Georgia, hunting with Leigh was unique. Where others would keep score on how many quail were brought down and how many shots were fired, Leigh knew that was not what was important. Instead, he kept a clipboard in the wagon with a list of his dogs and noted with a pencil which ones found or pointed the coveys of quail. It was not about “meat in the wagon,” but the graceful, elegant dogs afield that were family to him. Many a duck hunter at Mays Pond would find themselves in a natural blind of brush, keeping company with the headstone of a loyal retriever who once sat years or decades ago in the early morning light by the side of Leigh Perkins.

One great memory of Leigh and his love of dogs was from a stay at a PERC board meeting in Big Sky, Montana. Leigh and his wife Annie would travel everywhere with their assemblage of English setters. But the hotel was a strict “no dogs allowed” establishment, as they learned at check-in, so Leigh asked for a room on the backside of the lodge on the ground floor. That night, when it got dark, he and Annie enlisted me and my wife to help them pop out the mesh screen in the window well of their room. Then, like a well-trained military operation, he proceeded to orchestrate a human bucket brigade to usher four English setters from their truck to the lodge room through that small window well. How quintessentially PERCian in spirit!

The boyish resourcefulness in Leigh didn’t just extend to his beloved setters; it permeated his entire life. PERC board member Kim Dennis tells one story of a time she sat next to Leigh at a board dinner in Montana. Leigh had passed some fresh roadkill on the way to dinner but didn’t have time to stop to pick it up. All through dinner he kept obsessing over the missed opportunity. By the time he showed up at breakfast the next morning, with a big grin on his face, he could report that he had returned to the site, and the deer’s meat and organs were safely stored in his coolers.

Leigh was also defined by the women in his life. In the beginning, it was his mother, Katherine Perkins, a renowned sportswoman who fostered in Leigh a love of the outdoors, wildlife, and nature, if not his sense of mischievousness. He would tell me stories of hunting alligators with his mother and watching her shoot turkeys on the wing. One of the most endearing photos he kept at Mays Pond was of an elderly Katherine walking after her son, finger pointed at him, clearly scolding him for some mischief, as a middle-aged Leigh walks away head down with hands in his pockets. He said it was a photo of his mom “advising” him.

In the end, it was his loving wife and hunting and fishing partner Annie—a strong, intelligent, and charming outdoorswoman in her own right and longtime friend of PERC. After Leigh’s passing, I asked Annie if it was hard for them in his last year of life to be isolated from so many people because of Covid. On the contrary, she said. Though they missed family and friends, they got to spend an intimate year together fishing, hunting, watching wildlife, and taking in all the wonders of the outdoors until that magical hour of the day, when the soft evening light of the sun set on the legend, and man and nature merged into one. Leigh Perkins left us as he lived, the indomitable outdoorsman and conservationist.

After penning this tribute, I will head off to fish the evening hatch for colorful cutthroats in the pools and riffles of a tucked-away creek that empties into the Yellowstone River. Leigh would have surely encouraged that, and he probably would have suggested that I drop the writing and leave a few hours early. Mixing a love of the outdoors with meaningful conservation work is what Leigh inspired in so many of us who got to call him a friend. For the people at PERC, our passion is our work, and the work is a passion for the outdoors—that is the legacy of Leigh. PERC would not be what it is today without the friend we lost, the irreplaceable and immortal Leigh Perkins.