Since Congress passed the Great American Outdoors Act in 2020, billions of dollars have been devoted to repairing, restoring, and replacing critical assets at national parks.1U.S. Department of the Interior, “About GAOA,” accessed June 10, 2024, https://www.doi.gov/about-gaoa. So far, the landmark investment is helping reconstruct seawalls in the capital’s iconic Tidal Basin, rehabilitate potable water delivery throughout Canyonlands National Park, restore forestland in Cuyahoga Valley, stabilize a historic wharf at Alcatraz Island, and renew wastewater systems at Acadia National Park, along with numerous other projects.2National Park Service, “GAOA Stories,” accessed July 29, 2024, https://www.nps.gov/subjects/infrastructure/gaoa-stories.htm. National Park Service, “National Park Service Begins Reconstruction of Tidal Basin and West Potomac Seawalls,” News Release, August 15, 2024. National Park Service, “Utah Great American Outdoors Act Legacy Restoration Fund Fact Sheet,” 4. The act created the Legacy Restoration Fund to tackle these much-needed maintenance projects, funded by up to $1.9 billion annually from federal energy revenues. The National Park Service receives 70 percent of the total, or about $1.3 billion each year. More than 100 large-scale projects are underway, along with hundreds of smaller preservation activities, spanning all 50 states.3National Park Service, “National Parks and Public Land Legacy Restoration Fund,” accessed June 10, 2024, https://www.nps.gov/subjects/infrastructure/legacy-restoration-fund.htm.

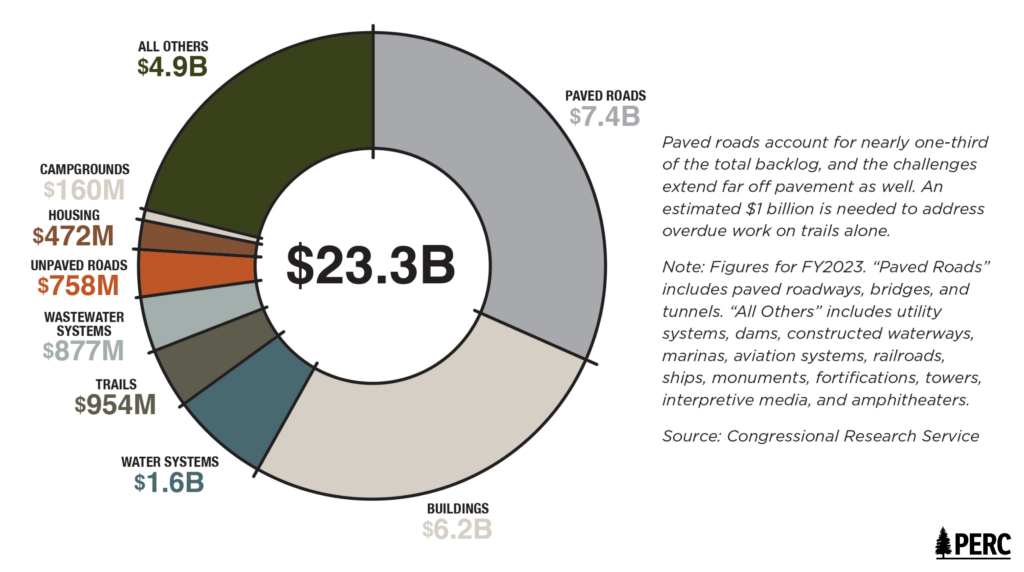

Given that the Legacy Restoration Fund expires at the end of September 2025, conservationists, advocacy groups, and lawmakers have begun to discuss the potential for reauthorizing it.4Laura B. Comay, “National Park Service Deferred Maintenance: Overview and Issues,” Congressional Research Service (July 25, 2024). Some members of Congress have criticized the National Park Service, however, because its maintenance backlog has grown rather than shrunk despite the generational investments of the act. For years, the agency has struggled to perform repairs and routine maintenance on time, leading to an accumulation of overdue, or “deferred,” projects. When the Great American Outdoors Act (GAOA) passed, the agency estimated its deferred maintenance backlog at $14.9 billion. The following fiscal year, its estimate ballooned to $23.7 billion.5U.S. Department of the Interior, Office of the Inspector General, “The National Park Service Faces Challenges in Managing Its Deferred Maintenance,” (September 2023): 6. Government oversight agencies have questioned the agency’s estimation methods, including an across-the-board markup attributed to inflation and a renewed effort to tally maintenance needs once the act offered the prospect of substantial funding. The current estimate stands at $23.3 billion.6Comay, National Park Service Deferred Maintenance: Overview and Issues, 4.

The reported maintenance backlog at national parks has grown for years, although government oversight agencies have questioned the estimates.

National Park Service deferred maintenance estimates by fiscal year.

Sen. Angus King (I-Maine) has described the surge in the backlog as “disheartening,” while Sen. Steve Daines (R-Mont.) lamented that it has grown “massively — virtually doubling.” The senators have also urged the agency to focus on routine maintenance, which extends the lifespan of infrastructure and prevents the backlog from growing even larger.7Rob Hotakainen, “Senators Lament Fast-Rising NPS Maintenance Backlog,” E&E News, May 11, 2023. Likewise, in the House, Rep. Bruce Westerman (R-Ark.) stressed that Congress was still waiting to see the expected reductions in the backlog after making historic investments in the park service.8Rob Hotakainen, “House Republicans Scold NPS for Costly Maintenance Backlog,” E&E News, July 28, 2023. “Instead of thinking we’re more than halfway through,” said Westerman, “and on pace to another five-year reauthorization to wipe out the maintenance backlog, we find we’re actually in worse shape than we thought we were in when approved GAOA to begin with.”9Molly Weisner, “National Parks Need $22 Billion to Address Growing Maintenance Backlog,” Federal Times, January 11, 2024.

Funding from the Great American Outdoors Act may be on its way to improving thousands of federal assets, but the picture has been muddled by a maintenance backlog that continues to grow as well as concerns over the politicization of project selection. While various aspects of the Legacy Restoration Fund have proven to be prudent and advantageous, the agency still faces long-standing problems in tracking and addressing maintenance. Those issues must be addressed for future park maintenance funding to be most effective. As the potential for reauthorization looms next year, the first iteration of the act offers several lessons in light of preexisting maintenance challenges at the National Park Service.

Since Congress passed the Great American Outdoors Act in 2020, billions of dollars have been devoted to repairing, restoring, and replacing critical assets at national parks.

Lessons Learned

The Great American Outdoors Act is funding crucial national park repairs and improvements, and its design has proven to be beneficial. Billions of dollars from GAOA have been directed to much-needed projects, from replacing failing wastewater systems to repairing eroded trails to rebuilding visitors centers. Various provisions of the act have been forward-looking, provided flexibility, and proven to be prudent, setting the agency up for success. For instance, the act allows unspent dollars in the Legacy Restoration Fund to be invested in U.S. Treasury bonds to earn interest, which can be used to cover program costs.

Yet the current deferred maintenance system is broken. The existing deferred maintenance system is not logical, accurate, or explainable. Government oversight agencies have repeatedly called into question various estimating methods used by the National Park Service. Moreover, the fundamental source of all deferred maintenance is a neglect of routine maintenance. The fixation on deferred projects takes attention away from the routine work that extends the lifespan of park assets, compounding the backlog challenges.

The broken approach to maintenance makes it difficult for the agency to defend its selection of projects and opens up the process to accusations of political bias. Because the system to estimate and track deferred maintenance is ambiguous and inconsistent, defending the selection of GAOA projects becomes more difficult and open to being politicized.

The agency risks jeopardizing potential reauthorization of the Great American Outdoors Act. Without changes to the deferred maintenance system, not only will the National Park Service struggle to overcome its maintenance challenges, but Congress may also be dissuaded from continuing to provide significant funding for them, making it even more difficult to address park system needs.

Long-Standing Maintenance Challenges

The National Park Service has struggled to maintain its roads, visitor centers, campgrounds, historic structures, trails, utility systems, and other assets for decades. Infrastructure in many parks dates back to the Civilian Conservation Corps era of the 1930s or the agency’s Mission 66 construction push of the ‘50s and ‘60s.10Comay, National Park Service Deferred Maintenance: Overview and Issues, 4. Much of it has reached or exceeded its anticipated lifespan without being repaired or replaced. The result has been a backlog of deferred maintenance, generally considered maintenance or repairs that were not completed on schedule.11Inspector General, The National Park Service Faces Challenges in Managing Its Deferred Maintenance, 4. As the backlog has swelled steadily over time, so has political salience of the issue.

Today, many of the units with the highest amounts of deferred maintenance are older parks, such as Yellowstone and Grand Canyon, with infrastructure largely constructed in the mid-20th century. Other units, including Gateway National Recreation Area, Golden Gate National Recreation Area, and the National Mall and Memorial Parks, are in urban areas, which require complex infrastructure and can also drive up labor and material costs. Similarly, large backlogs at the George Washington Memorial, Natchez Trace, and Blue Ridge Parkways reflect the relatively high share of deferred maintenance accounted for by paved roads ($7.4 billion, or nearly one-third of the total backlog).12Comay, National Park Service Deferred Maintenance: Overview and Issues, 2-7.

While there are questions over the accuracy of estimates, paved roads are a significant portion of the total reported maintenance backlog.

National Park Service deferred maintenance by type of asset

The Government Accountability Office has noted that “deferring or delaying maintenance can diminish the quality of an asset and, in the long term, can shorten the life and value of an asset,” ultimately leading to “significantly higher maintenance and repair costs.”13Government Accountability Office, “Deferred Maintenance: Agencies Generally Followed Leading Practices in Selections but Faced Challenges,” (January 2024): 1. To further complicate the matter, the agency has had no standard approach to classify which and when maintenance projects become “deferred.”14Inspector General, The National Park Service Faces Challenges in Managing Its Deferred Maintenance, 13. For its part, the agency has noted that root causes of the backlog include insufficient regular funding to care for park assets along with increases in construction costs, noting that until parks receive sufficient annual funding to adequately address recurring maintenance needs nationwide, the backlog will continue to grow.15Rob Hotakainen, “‘House of Cards’: Watchdog Slams NPS During Hearing,” E&E News, January 11, 2024.

The Inspector General Office of the Department of the Interior has described past deferred maintenance estimates as akin to “a house of cards built upon a house of cards.”16Hotakainen, ‘House of Cards’. In a 2023 report, it found that the agency was “unable to effectively identify and manage its deferred maintenance, in large part due to inaccurate and unreliable data” in the agency’s software management system, which relies on work orders recorded in the system.17Inspector General, The National Park Service Faces Challenges in Managing Its Deferred Maintenance, 1. The report cited significant failures to keep an updated accounting record of those work orders. Moreover, it questioned a blanket 35-percent markup applied to deferred maintenance projects in fiscal year 2021, intended to account for costs related to “compliance, design, construction management, and project management,” which had previously been excluded from estimates.18Inspector General, The National Park Service Faces Challenges in Managing Its Deferred Maintenance, 6. The markup resulted in a $3.7 billion increase in the backlog in a single year.19Inspector General, The National Park Service Faces Challenges in Managing Its Deferred Maintenance, 2. Note that NPS previously estimated “deferred maintenance” but now estimates “deferred maintenance and repairs,” which aims to capture the full cost of addressing overdue maintenance. The office also noted the long-term nature of the overall problem, adding that the agency has “struggled to manage deferred maintenance for at least two decades.”20Inspector General, The National Park Service Faces Challenges in Managing Its Deferred Maintenance, 11.

Relatedly, in early 2024, the Government Accountability Office reported that land management agencies attribute a portion of recent increases in deferred maintenance to “staff putting in more effort to log all deferred maintenance because of the increased funding available” from the Legacy Restoration Fund. When funding was limited, the office reported, “there was not an emphasis on logging complete data on all deferred maintenance needs because so much of it would not be funded.” The availability of funding, however, spurred agencies “to reevaluate their asset management approach and fostered a cultural change toward maintaining better data on deferred maintenance.”21GAO, Deferred Maintenance: Agencies Generally Followed Leading Practices, 14.

Nevertheless, the National Park Service has not adequately explained to Congress, the public, or federal oversight agencies why its maintenance needs continue to balloon despite generational investment from the Great American Outdoors Act. That’s partly because the agency’s deferred maintenance system is not logical, accurate, or explainable. Moreover, the focus on needs that have been “deferred” — which has no standard or consistent definition or classification — takes attention away from routine maintenance that extends the lifespan of park assets, ultimately compounding the challenge.

The National Park Service’s record of estimating, tracking, and addressing deferred maintenance would logically lead Congress to question the agency’s ability to handle future dedicated funding responsibly. Despite the muddled overall picture, however, the first iteration of the Legacy Restoration Fund is undoubtedly supporting hundreds of projects that are restoring critical infrastructure and assets for national parks.

Implementing GAOA 1.0

To date, the Legacy Restoration Fund has directed full funding of $1.3 billion to national parks each year. The National Park Service has already earmarked more than $4 billion for over 100 large-scale projects, along with 300 smaller-scale historic preservation activities.22NPS, National Parks and Public Land Legacy Restoration Fund. The Congressional Research Service has reported that projects funded from fiscal year 2022 to 2024 will address a total of $3.28 billion of the agency’s deferred maintenance needs, and if fiscal year 2025 projects are fully funded, they will address an additional $940 million of overdue maintenance.23NPS did not report similar estimates for FY2021 projects. Comay, National Park Service Deferred Maintenance: Overview and Issues, 15.

Moreover, Congress was prudent and far-sighted with several provisions of the act, including providing long-term flexibility, allotting contingency funding in case of budget overruns, and allowing funds to be invested to earn interest. The latter aspect has provided enough earnings to cover all of the act’s administrative costs.24Personal Correspondence, U.S. Department of the Interior GAOA Project Management Office, May 23, 2024.

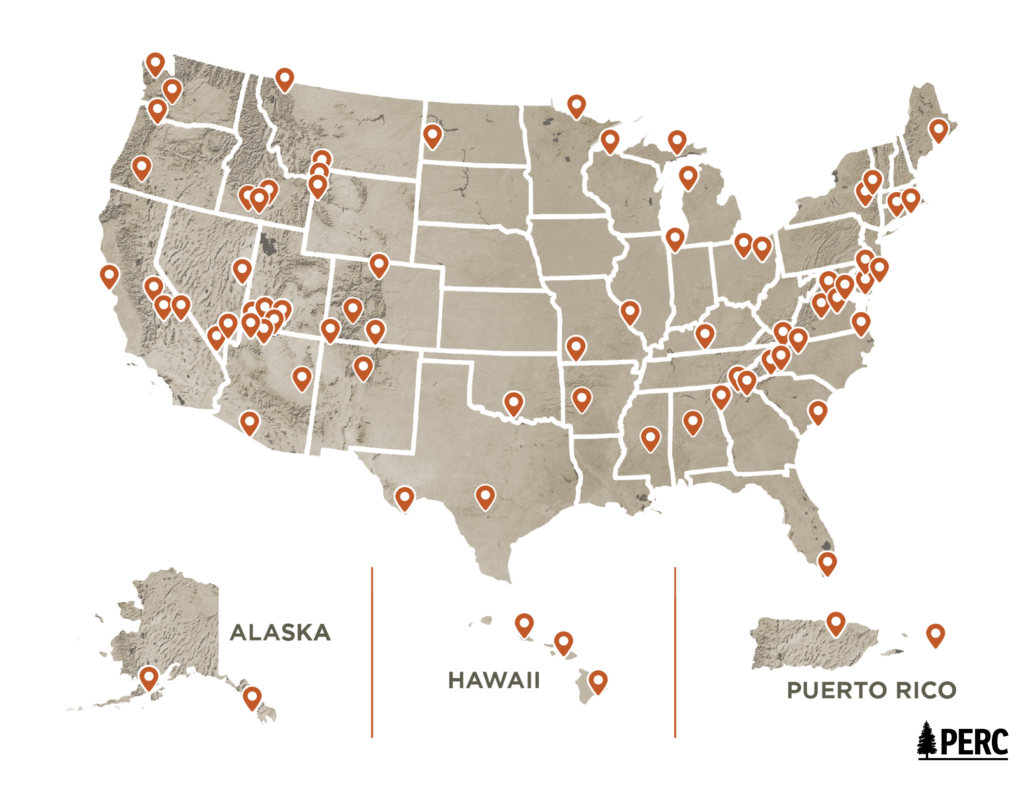

The Legacy Restoration Fund is supporting more than 100 major projects at National Park Service sites.

Great American Outdoors Act projects at U.S. national parks

The Government Accountability Office has reported that all agencies receiving funding from the act, including the National Park Service, generally followed appropriate standards when administering deferred maintenance projects under the act. For example, it reported that all agencies prioritized projects that presented safety threats if unaddressed.25GAO, Deferred Maintenance: Agencies Generally Followed Leading Practices. It also noted that the National Park Service initially selected projects at sites with high visitation and selected projects that were ready to be implemented quickly.26GAO, Deferred Maintenance: Agencies Generally Followed Leading Practices, 18-19.

The office has also documented why the amount of deferred maintenance addressed by a given project may be less than a project’s total cost. For one, project costs related to environmental approvals, planning requirements, or design processes might not be accounted for in deferred maintenance estimates. For another, a portion of projects that modernize infrastructure or bring assets up to code would likely not be classified as deferred. A project at the Mammoth Cave Hotel, for instance, includes removing a flat roof and rebuilding a pitched roof—more expensive than a simple replacement, but designed to reduce long-term maintenance costs.27GAO, Deferred Maintenance: Agencies Generally Followed Leading Practices, 17.

In general, the National Park Service focuses all of its investments on “important facilities and infrastructure that can be maintained in acceptable condition throughout their respective lifecycles,” according to the agency. Individual parks identify projects of need, and as project size and complexity increases, there are “escalating levels of scrutiny and review, with many projects requiring regional review and prioritization, and some requiring detailed review by headquarters staff and senior leadership.”28NPS FY2025 Budget Justification, SpecEx-3. The agency’s centralized Bureau Investment Review Board, made up of senior managers from across the agency, is the highest level of review. According to the GAOA Project Management Office, the board seeks to “provide leadership, direction, and accountability for major investment decisions” and “provides a service-wide policy perspective and oversight of major facility investments, helping parks to think more strategically about their facility and infrastructure investment proposals by considering park-wide needs, priorities, and logical construction sequences.”29GAOA PMO, Great American Outdoors Act: National Parks and Public Land Legacy Restoration Fund Strategic Plan, 14.

When it comes to selecting specific Legacy Restoration Fund projects, however, it is not clear how the agency has prioritized among its many needs. Given that local park staff have the best knowledge of their own needs and priorities, it makes sense to harness the bottom-up identification of priorities by individual parks. The details of the review processes at the regional and national levels, however, remain opaque. The agency touts that funded activities selected to date span “all 50 States, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and the US Virgin Islands,” suggesting one consideration may have been to disperse funding everywhere.30NPS, National Parks and Public Land Legacy Restoration Fund. That approach, however, risks a “peanut butter spread” that covers all geographic areas but is too thin to effectively address the highest priorities.

Moreover, some lawmakers have bemoaned the selection of projects. In 2022, House Natural Resource Committee Republicans alleged that the agency “in some cases, seems to prioritize funding for relatively obscure park units in urban areas over crown jewels of the National Park System in rural areas.”31Letter from Rep. Bruce Westerman, Ranking Member, H. Comm. on Nat. Res., et al., to The Hon. Debra Haaland, Sec’y, U.S. Dep’t of the Interior & The Hon. Thomas Vilsack, Sec’y, U.S. Dep’t of Agriculture (July 15, 2022). Republicans have specifically criticized a $161 million investment in the George Washington Memorial Parkway just outside of Washington, D.C.32Kelsey Brugger, “Republicans Investigate Spending on Parks, Outdoors Law,” E&E News, April 17, 2023. Additionally, they took issue that Rep. Nancy Pelosi’s (D-Calif.) congressional district was set to receive $166 million from the Legacy Restoration Fund for two park units, “an amount that could otherwise address the deferred maintenance backlog in eleven states totaling 35 park units,” the House Republicans wrote.33Letter from Rep. Bruce Westerman. In a similar vein, House Republicans decried $200 million in Inflation Reduction Act funding for the Presidio National Park Site in Pelosi’s congressional district. According to House Republicans: “During testimony before the Committee, Director Chuck Sams confirmed that the agency had not used the criteria supported by GAO [for the Presidio IRA funding] and instead had transferred hundreds of millions of dollars of taxpayer money at the direction of political officials at DOI.” Office of Rep. Bruce Westerman, Chair, H. Comm. on Nat. Res., Hearing Memo on “National Park Service’s Deferred Maintenance Backlog: Perspectives from the Government Accountability Office and the Inspector General,” Joint Subcommittee on Oversight and Investigations and the Subcommittee on Federal Lands (January 10, 2024).

Regardless of how projects have been selected, the appearance of selection based on political grounds rather than best practices presents a hurdle for prospects of future funding for parks. The perception that national parks have been unable to make progress on their long-standing maintenance challenges arguably presents an even more challenging hurdle. Lastly, the National Park Service’s failure to keep up with its maintenance needs in the past prompts the question of whether it will be able to properly steward the new investments funded by GAOA 1.0.

Recommendations

Various strategies can help the agency improve its approaches to national park stewardship and make potential reauthorization of the Great American Outdoors Act more attractive to lawmakers.

1. Replace the broken deferred maintenance system and terminology.

The National Park Service’s several-decade old system to estimate, track, and report deferred maintenance has failed. The Government Accountability Office and the Interior Department’s inspector general have called the system into question on various counts. Because the system is illogical, inaccurate, and unexplainable, it is indefensible. The agency is in the process of updating its system to one based partly on quick visual checks, known as parametric condition assessments.34Comay, National Park Service Deferred Maintenance: Overview and Issues, 8. The agency should harness the logical aspects of its emerging approach, such as the efficient parametric assessments and reliance on a preexisting Federal Highway Administration inspection framework,35The Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) works with the NPS to inspect transportation assets, including paved roads, parking areas, bridges, and tunnels. Comay, National Park Service Deferred Maintenance: Overview and Issues, 8. These assessments are combined with parametric condition assessments and inspection data for concessionaire-occupied assets to produce total deferred maintenance estimates. Inspector General, The National Park Service Faces Challenges in Managing Its Deferred Maintenance, 11. and completely implement a new system for estimating its maintenance needs.36For more details, see NPS FY2025 Budget Justification, SpecEx-1. Additionally, the agency should consider simplifying and better defining its asset classes in an effort to improve prioritization.

Perhaps just as importantly, the agency should also reframe the issue more logically and accurately by developing new terminology to discuss maintenance, whether it be routine, deferred, or otherwise. Rather than arbitrary measures of what merits a project becoming “overdue,” the ultimate focus should be on less-subjective factors — such as safety and visitation. If many people’s lives will be put at risk in case of a major bridge failure, for instance, then that bridge should be a top priority. But prioritizing thousands of agency projects has become virtually impossible with a broken system. New terminology, framing, and communication of the issue will not only help the agency manage parks but also explain its maintenance needs and their prioritization to Congress, taxpayers, and visitors.

2. Devote future GAOA funding toward sound stewardship generally and jettison the focus on “deferred” maintenance.

If Congress stipulates that funding can only be used on deferred maintenance, then the message to agencies is that park infrastructure must be in a state of disrepair before it can be repaired or replaced. Moreover, setting aside the various long-standing issues with estimating, tracking, and reporting deferred maintenance, the National Park Service has had no uniform determination of what comprises “deferred” maintenance or when something becomes “deferred,” rendering the term virtually meaningless. Congress should avoid “deferred” terminology and refrain from tying funding to it. Instead, it should direct parks to focus on improving stewardship generally, using logical, less-subjective criteria so that all visitors will be able to enjoy parks for generations to come.37Tate Watkins, “Fixing National Park Maintenance for the Long Haul,” PERC Policy Brief (2020).

3. Protect investments made through GAOA 1.0.

The Great American Outdoors Act has already devoted billions of dollars to national parks. It makes little sense to have invested such significant resources into 1.0 projects only for agencies to fail to steward the assets rehabilitated and built through them.38For more on prioritizing the maintenance of existing park assets, see Watkins, Fixing National Park Maintenance for the Long Haul, 6. Congress should ensure that a sufficient portion of any future Legacy Restoration Fund is dedicated to maintaining and protecting the value of investments from GAOA 1.0.

4. Retain aspects of GAOA 1.0 that have proven useful and successful.

Interest earnings: The GAOA Project Management Office has highlighted the importance of the ability to earn interest from the Legacy Restoration Fund through U.S. Treasuries, which helps pay for administrative costs and cover project cost overruns. The fund had earned approximately $77 million in interest as of fiscal year 2023 and is expected to earn an additional $197 million in fiscal year 2024. Interest earnings have already covered all administrative costs of GAOA at the department and agency levels.39GAOA Project Management Office.

Long-term flexibility: The Government Accountability Office has praised the general flexibility of the Legacy Restoration Fund, noting that it does not expire nor need to be spent in a particular time frame. That flexibility helps given that many construction projects are long term, and often there are contractor delays or price increases due to inflation.40GAO, Deferred Maintenance: Agencies Generally Followed Leading Practices, 22-23.

Nimble workforce: The Government Accountability Office has also praised agencies’ ability to use funds to maintain, train, and expand internal maintenance teams who complete straightforward tasks and practice various trades at small scale with relatively quick turnarounds. Examples of work performed by these “maintenance action teams” include rebuilding trail boardwalks, rehabilitating window shutters on historic buildings, preserving historic aqueducts, and removing debris.41U.S. Department of the Interior, “Maintenance Action Teams,” accessed June 10, 2024, https://www.doi.gov/gaoa-maintenance-action-teams. For smaller, simpler projects that may not warrant the time and complexity required to navigate federal bidding and contracting processes, internal teams have been able to carry out work more quickly and at a lower cost than would have been the case with contracted work.42GAO, Deferred Maintenance: Agencies Generally Followed Leading Practices, 22.

Contingency funding: The Government Accountability Office notes another benefit is the inclusion of contingency funds that can be used to deal with unforeseen cost overruns if certain requirements are met. These contingency funds allow agencies more flexibility to deal with inflation and other challenges and address deferred maintenance.43GAO, Deferred Maintenance: Agencies Generally Followed Leading Practices, 22-23.

5. Select projects based on appropriate criteria that maximize impact and limit political influence over spending.

As GAOA criteria suggest, safety and visitation should have significant weight when selecting projects. The National Park Service should assess what assets would fail absent attention and weigh the risk of failure in conjunction with how seriously and how many people would be impacted in the event of infrastructure failure. Such an approach would suggest that, for instance, assets like highly trafficked roads, overnight facilities, and wastewater treatment facilities be prioritized. It would also suggest that, at a system-wide scale, the agency would weigh repair or replacement of a rarely used bridge in a remote area much less than a bridge used by a million visitors a month.

Likewise, ensuring sufficient availability of safe and quality employee housing would be prioritized given that at many parks, serving visitors hinges on being able to hire, house, and retain employees in agency housing. Senators King and Daines have highlighted the challenge of employee housing shortages, which affect parks from Acadia to Grand Teton and Yellowstone and beyond, and they proposed legislation aimed at addressing the problem.44Office of Sen. Angus King, Chair, S. Subcomm. on Nat. Parks, “Daines, King Introduce Bill to Reduce Crowding on Public Lands and Support Partnerships with Gateway Communities,” February 2, 2022. Rob Hotakainen, “NPS Employees Face a Worsening Housing Crunch as Prices Soar,” E&E News, February 1, 2022. Yellowstone National Park is in the process of a major, multi-year effort to improve employee housing, which includes replacing dilapidated and at times unlivable trailers with modular homes, updating stand-alone homes, restoring historic structures, and adding new employee housing capacity. The strategic effort has saved tens of millions of dollars by leveraging modern building techniques and has been supported by donations. The park’s creative and successful plan could serve as a model to be expanded at other sites as applicable.45National Park Service, Yellowstone National Park, “Focusing on the Core,” accessed July 29, 2024, https://www.nps.gov/yell/learn/management/focusing-on-the-core.htm. National Park Service, Yellowstone National Park, “Yellowstone Announces Major Employee Housing Improvement Initiative,” News Release, February 19, 2020.

Transparently ranking agency projects based on factors such as safety, visitation, and the ability to house an adequate workforce, rather than soft goals such as geographic equity, will be the most effective way for the agency to address its maintenance challenges and avoid perceptions of politicization.

6. Explore creative innovations to visitor fees that can complement GAOA investments.

National Park Service receipts from entrance and recreation fees have played an increasingly important role at many national parks as visitation has boomed in recent years.46Tate Watkins, “Enhancing the Public Lands Recreation Fee System,” PERC Policy Brief (2020). Empowering parks to innovate with their fee structures and the use of their receipts would help complement investments from the Legacy Restoration Fund, whether directly by contributing to rehabilitation and repair projects or indirectly by helping cover routine maintenance and other needs in ways that help stretch park budgets.

Ideas include granting more authority to park superintendents to set fees and experiment with creative structures while harmonizing with peer parks, eliminating agency directives that tie the hands of superintendents when it comes to spending fee revenues, and clarifying that managers are permitted to use their fee receipts for operations and permanent visitor-service employees.47Watkins, Enhancing the Public Lands Recreation Fee System. Shawn Regan et al., “Breaking the Backlog: 7 Ideas to Address the National Park Deferred Maintenance Problem,” PERC Public Lands Report (2016). Relatedly, parks could be encouraged to explore ways to implement a surcharge for overseas visitors.48Tate Watkins, “How Overseas Visitors Can Help Steward Our National Parks,” PERC Policy Brief (2023). The agency should also consider raising the price of its annual recreation pass to reflect the value it provides and keep its pricing in line with individual park fee structures.49Watkins, Enhancing the Public Lands Recreation Fee System, 8.

7. Consider regular reauthorization of the Legacy Restoration Fund that would allow the park service to make long-term plans to recapitalize assets.

Much like in the private sector, recapitalizing assets and infrastructure will often call for special funding sources. Regularly devoting federal energy revenues to parks through the Legacy Restoration Fund, perhaps through consistent five-year reauthorization of the program, could provide a realistic plan for recapitalizing park assets over the long haul. Otherwise, a lack of certainty over reauthorization hinders long-term planning.50For example, the Government Accountability Office has reported: “According to officials at the four land management agencies, the short-term nature of the LRF can create challenges with hiring. The LRF is designed as a 5-year program through 2025; however, construction projects to address deferred maintenance may take longer. Therefore, agencies could face difficult decisions on whether to hire (1) an employee to serve a 5-year term that might end during the project, or (2) a permanent employee they might not be able to justify in their budgets after the LRF funding ends.” GAO, Deferred Maintenance: Agencies Generally Followed Leading Practices, 22. Relatedly, legislators may wish to explore new complementary or alternative user-based options to help fund park stewardship over the long term.51See, for instance, Tate Watkins and Jack Smith, “A Better Way to Fund Conservation and Recreation,” PERC Policy Brief (2020), and Tate Watkins, “Leave No Trace?” PERC Reports 36, no. 2 (Winter 2017).

8. Recognize that maintenance needs will never “zero out” and instead focus on how much and what types are acceptable.

The National Park Service maintains more than 70,000 assets that are worth nearly $200 billion. The moment a ribbon is cut on a new bridge, visitor center, or campground bathroom, it begins to deteriorate. The agency should be upfront about what portion of maintenance needs it will have at a given time and set expectations with Congress and the general public accordingly. It should also make clear that the acceptance of outstanding maintenance will be different for different assets — well-traveled bridges or wastewater treatment facilities, for instance, should always be prioritized over less crucial assets. Relatedly, the agency should explore options to dispose of underused or defunct assets or transfer parkways or commuter roads to state or local entities wherever feasible.52Watkins, Fixing National Park Maintenance for the Long Haul, 7-8. Painting a realistic picture of what it takes to maintain roughly $200 billion of infrastructure can help the agency frame the scale and scope of its maintenance challenges and set realistic expectations.

Conclusion

The Legacy Restoration Fund is helping repair and restore neglected assets at national parks across the country, and many aspects of the fund’s creation through the Great American Outdoors Act have set it up for success. Yet long-standing problems with the National Park Service’s methods to track, report, and address maintenance continue to plague the agency. As the potential for reauthorizing the program looms, the above recommendations would not only bolster confidence in the agency to steward funding for maintenance but also help ensure national parks will be properly cared for now and into the future.

Go Deeper:

How Overseas Visitors Can Help Steward Our National Parks

Fixing National Park Maintenance for the Long Haul

Enhancing the Public Lands Recreation Fee System

A Better Way to Fund Conservation and Recreation

Breaking the Backlog: 7 Ideas to Address the National Park Deferred Maintenance Problem