Introduction

The Department of the Interior plays a vital role in stewarding America’s vast natural resources. As a new administration takes the reins, it has an opportunity to prioritize conservation outcomes while streamlining government processes and delivering solutions that benefit both people and the environment. To seize this opportunity, the administration should set the following goals to recover wildlife, enhance land stewardship, and promote the responsible use of America’s natural resources:

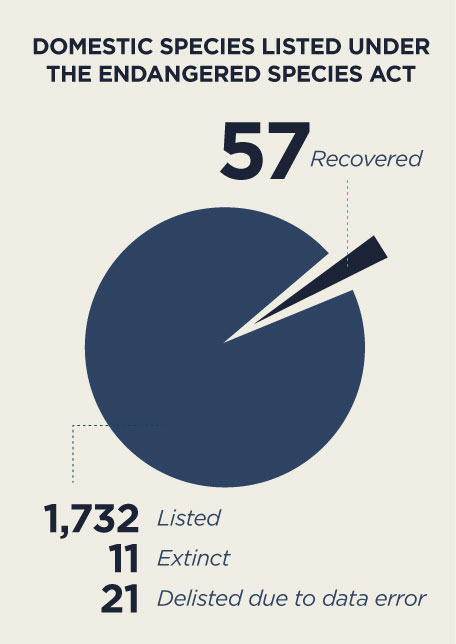

1. Triple the rate of endangered species recovery to 10 percent by recovering an additional 120 species. Despite half a century of efforts under the Endangered Species Act, recovery rates for listed species remain low, with only 3 percent achieving delisting due to recovery. Regulatory reform that rewards innovation, encourages private conservation efforts, and provides greater certainty can dramatically improve outcomes.

2. Delist grizzly bear populations in recognition of their remarkable recovery success. Endangered species that meet objective recovery benchmarks, as two grizzly populations have, should have clear off ramps to be delisted. This would reward rather than punish a species’ growth and expansion.

3. Cut to 60 days the time taken to issue voluntary conservation benefit agreements for endangered species. The vast majority of listed species rely on active management, needing habitat restoration and recovery efforts to survive. But these efforts require federal permits that can take a year or longer to receive, which can deter landowners, states, and agencies from taking action.

4. Double fee revenues to improve stewardship of national parks by charging international visitors more and implementing other smart pricing ideas. National parks, the crown jewels of America’s public lands, are straining from booming visitation. Sensible pricing can boost the revenue that visitors contribute to parks, providing resources to properly steward these iconic places.

5. Stop the growth of the national park deferred maintenance backlog. Devolving authority and increasing flexibility will help responsibly maintain park infrastructure and conserve natural and cultural resources for future generations.

6. Double annual wild horse adoptions to 12,000 to curb overpopulation on public rangelands and save taxpayers hundreds of millions of dollars. Addressing the wild horses and burros crisis on public lands will align ecological health with fiscal responsibility. Increasing adoptions can reduce ecological pressure while saving taxpayers hundreds of millions of dollars in management costs.

7. Advance grazing policy for the 21st century by shifting from prescriptive rules to results-driven management. Modernizing grazing policy can simultaneously bolster the economic resilience of ranchers and improve rangeland health. Voluntary approaches that promote the adoption of virtual fencing technology and harness outcome-based grazing strategies will help ranchers and public rangelands alike.

8. Increase fuel treatments by 25 percent, to 3 million acres per year, to mitigate wildfire risk and improve forest health. Rapidly scaling fuel treatments on department forestlands—through prescribed burning, mechanical thinning, and collaboration with state and private partners—is essential for restoring healthy forests and safeguarding communities.

9. Pilot two true co-management agreements of national monuments with tribes. Native Americans have deep ties to their ancestral lands, which are vital to their cultures and economies, yet federal policies restrict their control over tribal resources. Empowering tribes to manage their land, forests, and water will benefit tribal communities and encourage accountable stewardship.

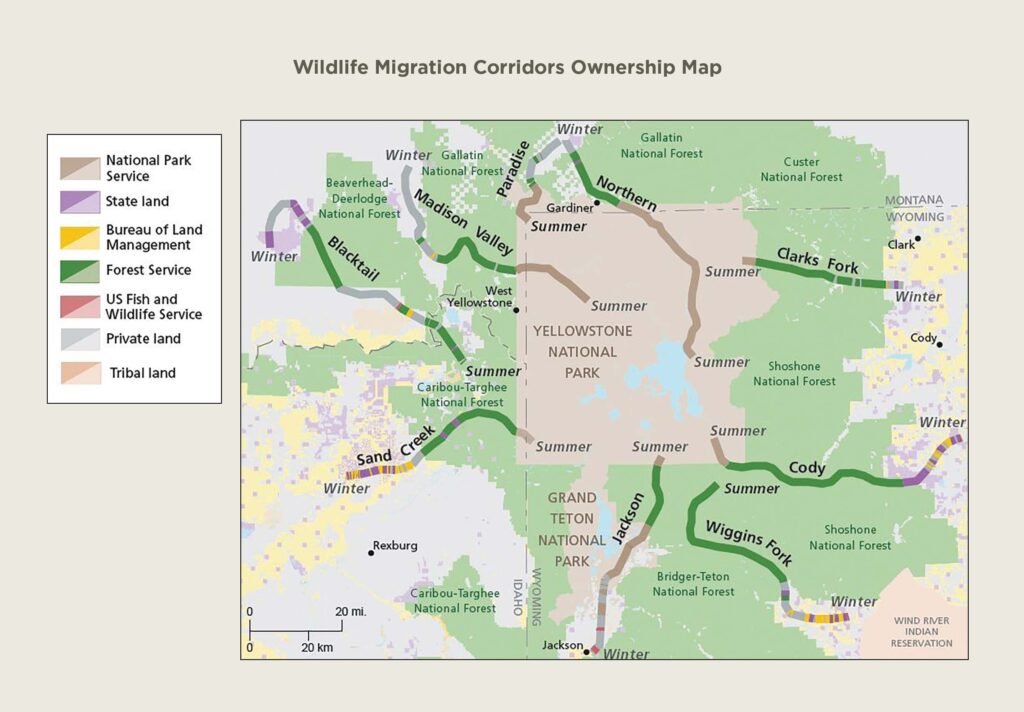

10. Conserve the 10 highest-priority western migrations using voluntary, locally led, incentive-based approaches. Collaborative conservation can reward landowners for maintaining and enhancing critical migration corridors for big-game wildlife.

This report offers a roadmap of actionable reforms aimed at achieving these goals specifically while also improving conservation outcomes more broadly. The strategies outlined within complement priorities of the new administration, including regulatory streamlining, permitting reform, and government efficiency. Each reform is grounded in PERC’s long-standing approach of harnessing the power of markets, incentives, and property rights to achieve better environmental outcomes.

1. Fix the Perverse Incentives Holding Back Species Recovery

To recover more species, the department should center recovery in its decision-making and focus on providing incentives for states and private landowners to restore habitat and recover species.

Goal: Triple the rate of endangered species recovery to 10 percent by recovering an additional 120 species.

Since the Endangered Species Act was enacted a half-century ago, about 60 of the more than 1,700 listed species have achieved delisting due to recovery, meaning only 3 percent of endangered and threatened species have ever recovered. A primary obstacle to recovery is the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s heavy reliance on regulatory penalties, which turn rare species into liabilities for private landowners. Two-thirds of listed species depend on private land for their survival, yet punitive regulations discourage habitat conservation and recovery efforts.

The ESA makes “conservation,” defined as recovering species to the point that they are no longer endangered or threatened, the standard for every major regulatory decision. Yet the Fish and Wildlife Service rarely considers how its decisions affect species’ recovery prospects, especially how those decisions affect state and private landowner incentives to invest in habitat restoration and other recovery efforts. Instead, the agency often assumes, without evidence or justification, that more regulation is always better.

Policy Recommendations

The department should aim to drastically improve the recovery rate of endangered species long term. As a starting point, the following reforms can help triple the rate of recovery to 10 percent, which would mean roughly 120 additional species achieve recovery.

1. Rescind the “wet blanket rule” and use regulations for threatened species to reward recovery progress: The Fish and Wildlife Service’s illegal “blanket rule” imposes endangered-level regulation on threatened species without any consideration of whether that’s good for the species. Instead, regulation of threatened species should relax as species recover as an incentive for states and private landowners to restore habitat and invest in recovery efforts.

Read more: A Field Guide for Wildlife Recovery, Ch. 1 and Ch. 4.

2. Only designate areas as critical habitat where the designation will encourage habitat conservation and species recovery: Critical habitat designations can reduce property values, increase permitting requirements, and alienate private landowners. Yet, when designating critical habitat, the Fish and Wildlife Service does not consider how its decisions affect landowners’ incentives to recover species.

Read more: A Field Guide for Wildlife Recovery, Ch. 5.

3. Reverse federal rules that nullify the ESA’s federalism provisions so that states can lead on recovery: The ESA requires the Fish and Wildlife Service to “cooperate to the maximum extent practicable with the States” and gives states substantial authority to decide how listed species should be regulated. Federal regulations, however, have withheld this authority from states.

Read more: A Field Guide for Wildlife Recovery, Ch. 6.

4. Align regulations with recovery plans: The ESA requires a recovery plan for each listed species. However, the service does not develop these plans until after it makes every controversial regulatory decision affecting species, meaning that these plans and the need to work with states and private landowners do not inform key decisions.

Read more: A Field Guide for Wildlife Recovery, Ch. 2.

2. Reward, Don’t Punish, Endangered Species Expansion

The ultimate goal of the Endangered Species Act is to recover wildlife populations to the point that they can be delisted. But the service’s approach to identifying those populations and delisting them provokes needless conflict and frustrates recovery.

Goal: Delist grizzly bear populations in recognition of their remarkable recovery success.

The Endangered Species Act allows not only the listing of species but also subspecies and distinct population segments of species. The law also allows the service to identify a distinct population segment within a listed species and separately delist that segment. Through these tools, the service can tailor its listing and delisting decisions to reflect how threats and recovery progress may vary across populations.

Recent decisions by the Fish and Wildlife Service undermine this process, while provoking conflict and frustrating recovery. The service recently rejected petitions to delist grizzly bears around Yellowstone and Glacier National Parks on the grounds that those populations had recovered too much and had begun to naturally connect. Therefore, neither population qualified as a distinct population segment. And where the service has successfully delisted recovered populations, it has failed to account for their continued growth. As gray wolves from the recovered Northern Rocky Mountains population expand into other states, that conservation progress is not rewarded but instead punished with strict regulation.

Policy Recommendations

As it seeks to reward rather than punish endangered species recovery, the department should:

1. Require species to be proposed for delisting when recovery goals have been met: Letting recovered species linger on the list provokes conflict and saps resources that could recover other species. Yet the service often declines to act on its scientists’ findings that species have met recovery goals.

Read more: A Field Guide for Wildlife Recovery, Ch. 2.

2. Revise policy to make distinct population segments a durable entity: To motivate recovery efforts, distinct population segments must be durable, rather than coming in and out of existence as conditions change. In particular, the service should establish that a distinct population segment cannot lose its status by recovering “too much.”

Read more: A Field Guide for Wildlife Recovery, Ch. 4.

3. Reward, rather than penalize, the expansion of a recovered population’s range: When recognizing a distinct population segment, the service should account for the population’s continued growth in numbers and expansion in range. And where a population grows beyond the initial boundaries set by the service, it should promptly revise those boundaries to reflect that growth.

Read more: A Field Guide for Wildlife Recovery, Ch. 4.

3. Cut Green Tape for Endangered Species Conservation

The Endangered Species Act ensnares conservation in a slow, costly, and opaque permitting process. Reforms will free up federal agencies, states, and landowners to conserve habitat.

Goal: Cut to 60 days the time taken to issue voluntary conservation benefit agreements for endangered species.

Approximately 80 percent of listed species are “management dependent,” meaning that they will not recover if left alone. Instead, these species require proactive habitat restoration and recovery efforts. The ESA, however, often hinders these recovery activities by imposing strict regulatory requirements and requiring costly and time-consuming federal permits, which can discourage federal agencies, states, and landowners from undertaking them. For 85 percent of listed species, less than a quarter of the needed recovery efforts identified in the species’ recovery plan have been completed.

Permitting is a significant drain on the service, other federal agencies, states, and private landowners. A private landowner who wants to restore habitat or reintroduce a species can spend more than nine months negotiating a “safe harbor agreement” with the service. And federal agencies must consult with the service over thousands of projects each year, including projects to maintain or restore habitat, even though almost none of them will jeopardize a listed species or harm critical habitat.

Policy Recommendations

To advance the goal of issuing voluntary conservation benefit agreements within 60 days, and to promote endangered species conservation more generally, the department should:

1. Remove permitting obstacles to voluntary conservation: While the service has several programs to permit and encourage conservation actions, it can take months or years to navigate these programs. The service should develop general permits and similar tools to allow landowners easy access to these programs.

Read more: A Field Guide for Wildlife Recovery, Ch. 8.

2. Delegate permitting authority to states: The ESA gives the service broad discretion in designing the act’s permitting process. It should exercise this authority to give states power to issue permits for most regulated activities, especially those with only local effects.

Read more: A Field Guide for Wildlife Recovery, Ch. 6.

3. Reform the consultation process to reward federal agencies that effectively restore habitat and conserve species: Service regulations require federal agencies to consult the service over any projects that “may affect” a listed species or its critical habitat. The service should issue regulations reducing consultation requirements for agencies that have developed programs to conserve species under section 7(a)(1) or that have proven effective at conserving species.

Read more: A Field Guide for Wildlife Recovery, Ch. 9.

4. Get Smart About the Way We Fund Our National Parks

National parks face mounting challenges to serve growing numbers of visitors. By charging overseas visitors more and further refining the fee system, the department can generate sustainable revenue for park stewardship.

Goal: Double fee revenues to improve stewardship of national parks by charging international visitors more and implementing other smart pricing ideas.

The National Park Service manages 425 units, including iconic sites such as Yellowstone, Yosemite, and the Grand Canyon. After recent booms in visitation, however, America’s national parks are struggling to keep pace with their popularity. Visitor fees offer a direct and sustainable mechanism to steward sites straining under visitation because as visits rise, so does revenue devoted to parks. Fees also depoliticize funding because they are spent where they’re collected without being subject to congressional appropriation.

Roughly 14 million international visitors frequent U.S. national parks annually, yet they pay the same entry fees as domestic visitors, even though their ability and willingness to pay are generally higher. This approach misses an opportunity to link park funding more closely with visitation demand—and adopt a strategy common at national parks in other countries around the world. Furthermore, the current fee structure does not account for variability in visitor profiles, trip costs, or the strain on park resources caused by different groups.

Policy Recommendations

In an effort to double fee revenues across the national park system, the department should:

1. Introduce a surcharge for international visitors to generate dedicated revenue for park maintenance and improvements: Currently, U.S. taxpayers pay more for national parks than visitors from abroad, because citizens pay twice—through taxes as well as at park gates. Evidence suggests surcharges would have minimal impact on visitation while potentially doubling current fee revenues. Implementing this policy would require minimal changes to fee collection systems and could initially be piloted at heavily visited parks, such as Yellowstone and the Grand Canyon, to gauge effectiveness before broader application.

Read more: How Overseas Visitors Can Help Steward Our National Parks.

2. Get creative with fee structures: The previous Trump administration proposed increasing visitor fees to better reflect the enormous value of U.S. national parks, before eventually raising them modestly. Experimenting with creative pricing models tailored to local conditions and visitor behavior can help alleviate stress on parks and provide resources to care for them properly. Examples include discounts for off-peak visitors or local residents, charges per person rather than per vehicle, higher fees during peak times, and prices that vary based on group size or visit duration.

Read more: A Path Forward for America’s Best Idea and Enhancing the Public Lands Recreation Fee System.

3. Raise the price of the America the Beautiful Pass: Increasing the price of the $80 annual pass to reflect its immense value could generate substantial additional revenue. It would also more closely align with the cost of similar passes offered by state park systems or private attractions.

Read more: A Path Forward for America’s Best Idea and Enhancing the Public Lands Recreation Fee System.

5. Empower National Park Superintendents with Maintenance and Operational Flexibility

Local park leadership is best positioned to understand and address their parks’ unique challenges. By granting superintendents greater autonomy and holding them accountable, the department will empower local solutions and stop digging a maintenance hole.

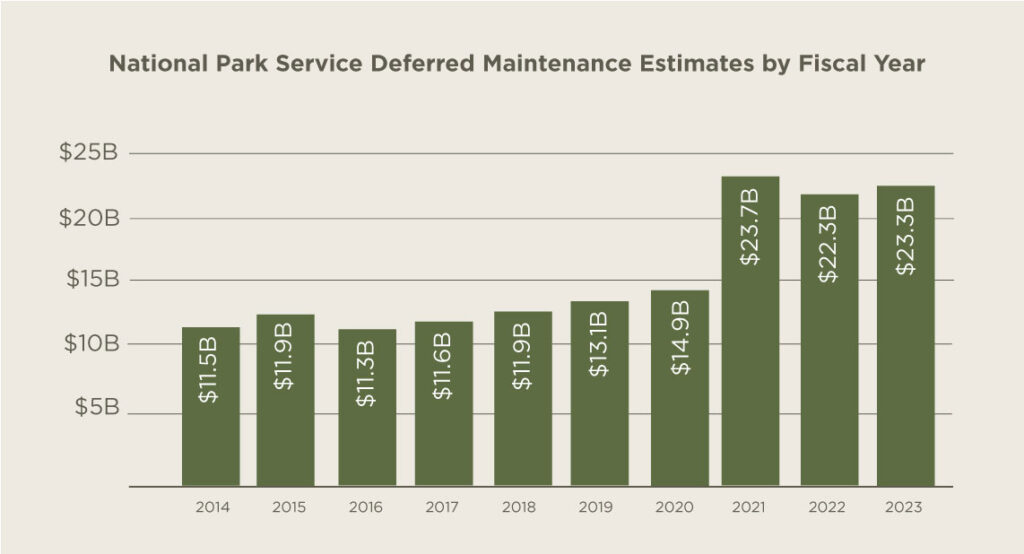

Goal: Stop the growth of the national parks deferred maintenance backlog.

National parks face $22 billion in deferred maintenance, with critical issues ranging from eroding trails to failing water systems. The root of the backlog is neglect of the routine maintenance essential for visitor safety and park preservation. Park superintendents are better positioned than distant bureaucrats to identify and address site-specific challenges that will stop the growth of the backlog, but they have limited flexibility to do so.

Bureaucratic mandates hinder local managers from addressing maintenance and operational needs. For example, a rule requiring 55 percent of fee revenues go toward deferred maintenance limits flexibility and discourages proactive upkeep. It signals that parks should wait until something falls apart before addressing it. Similarly, superintendents lack the ability to adjust staffing and operations to fit their needs. While reducing the massive backlog may be beyond individual park leaders, granting them more authority while holding them accountable can help prevent further increases.

Policy Recommendations

To stop the growth of the park maintenance backlog, the department should:

1. Let superintendents prioritize their own maintenance needs and hold them accountable for their decisions: If funds can only be used on deferred maintenance, then the message is that assets must be falling apart before they can be repaired or replaced. By removing centralized directives, including the one that requires 55 percent of fee revenues to go to deferred maintenance, local managers can better align spending with needs. For example, a superintendent might prioritize repairing a frequently used hiking trail over less critical long-term projects, improving the visitor experience and reducing safety risks. Shifting authority to the local level also promotes accountability because it becomes clear exactly who is responsible for spending decisions.

Read more: A Path Forward for America’s Best Idea and Fixing National Park Maintenance For the Long Haul.

2. Shift more responsibility over staffing and operations to local superintendents, enabling them to adopt innovative and tailored solutions: Likewise, superintendents should be given greater flexibility to use fees to meet staffing needs and make operational decisions, while being held accountable for their actions. Empowering local managers to adjust staffing levels will help manage seasonal visitation peaks and result in more efficient and effective park operations generally.

Read more: A Path Forward for America’s Best Idea and Enhancing the Public Lands Recreation Fee System.

6. Conserve Public Land Ecosystems by Supercharging Wild Horse Adoptions

The growth of wild horse and burro populations on public lands undermines ecosystem health, wildlife conservation, and fiscal sustainability. The department should continue to harness adoption incentives and leverage partnerships to increase placements.

Goal: Double annual wild horse adoptions to 12,000 to curb overpopulation on public rangelands and save taxpayers hundreds of millions of dollars.

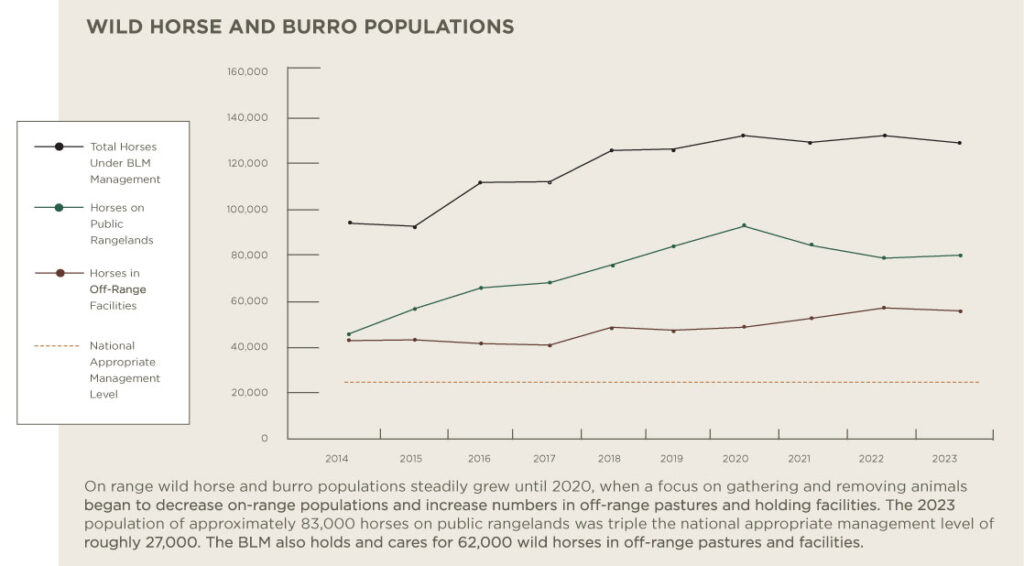

In 1971, Congress directed the Bureau of Land Management to protect wild horses and burros and maintain sustainable populations of them. Today, their numbers on public lands are nearly triple the agency’s threshold, leading to overgrazing, habitat degradation, and displacement of species like sage grouse and elk. Tens of thousands more horses are kept in off-range facilities, costing taxpayers over $100 million annually.

To curb these costs, the first Trump administration launched the adoption incentive program to provide a $1,000 payment to qualified adopters of an untrained wild horse who commit to its care for at least one year. This incentive, inspired by PERC research, aims to reduce the number of animals in government care by encouraging private adoption. A recent legal ruling halted the program on the grounds that it was not established through the proper procedures. Through its first five years, the program helped double total adoptions, reduced long-term housing costs, and will save taxpayers $400 million over the lifetimes of the adopted horses.

Policy Recommendations

To double annual wild horse and burro adoptions to 12,000 and reduce pressure on public rangelands and taxpayer resources, the department should:

1. Reinstate and defend the adoption incentive program: Average total adoptions of wild horses and burros more than doubled after the implementation of the incentive. The BLM should reestablish the program as soon as practicable and continue its successful use to adopt out the animals and reduce the long-term costs of caring for them.

Read more: From Range to Ranch

2. Experiment with innovative strategies like longer-term incentive payments to increase adoptions: The BLM should pilot alternative structures to further boost adoptions. For instance, multiple payments over several years or higher payments for adopting older or harder-to-place horses could enhance program reach and efficiency.

Read more: From Range to Ranch

3. Harness private partnerships to place even more wild horses and burros with adopters: Expanding collaborations with the Foundation for America’s Public Lands and private organizations can connect more adopters, especially those in eastern states, with available horses. Targeting regions with high demand for horses can boost placements and further reduce the burden on federal holding facilities.

Read more: From Range to Ranch

7. Give Ranchers Opportunities to Profit from Conservation

The department can support ranchers in adopting practices that enhance the economic viability of grazing operations and the ecological resilience of public rangelands.

Goal: Advance grazing policy for the 21st century by shifting from prescriptive rules to results-driven management.

The Bureau of Land Management manages 155 million acres for grazing, rangelands that are critical for livestock ranching, biodiversity conservation, and watershed health. These lands are increasingly stressed by invasive species, persistent drought, and decades of inconsistent management. The challenges to achieving both productive rangelands and healthy ecosystems require cooperative approaches that empower ranchers as stewards of these lands.

Traditional grazing practices often struggle to adapt to evolving environmental conditions and changing societal expectations. Overly rigid regulations and outdated infrastructure can hamstring innovative solutions that benefit ranchers and improve conservation outcomes. To address these challenges, federal policies must focus on modernizing grazing systems and fostering cooperation between ranchers, conservationists, and government agencies.

Policy Recommendations

To modernize federal grazing policies and give ranchers opportunities to profit from conservation, the administration should:

1. Make it easy to convert traditional barbed wire to virtual fencing: Virtual fencing technology allows ranchers to track and control livestock movement using GPS-enabled collars and digital boundaries. This technology can drastically reduce the costs of building and maintaining traditional fences, improve rotational grazing practices, protect sensitive riparian areas, and benefit wildlife by removing physical barriers within ranches or grazing allotments. Federal grazing policy should embrace virtual fencing systems and streamline permitting and regulation of them.

Read more: Unlocking the Conservation Potential of Virtual Fencing

2. Expand outcome-based grazing: Outcome-based grazing prioritizes rangeland health over prescriptive management practices, allowing ranchers to tailor flexible strategies to their specific landscapes. This approach fosters innovative solutions that balance productivity with stewardship. Permanently authorizing the BLM’s outcome-based pilot program and streamlining approval processes for outcome-based grazing agreements will enable ranchers to take a more active role in rangeland restoration efforts.

Read more: Opening the Range: Reforms to Allow Markets for Voluntary Conservation on Federal Grazing Lands

3. Empower ranchers to manage their grazing operations and profit from stewardship: Federal grazing regulations often micromanage ranchers and hinder their ability to respond to changing environmental and market conditions. Ranchers should have the flexibility to manage their operations without risking permit cancellation, forage reallocation, or formal reduction of authorized grazing, including negotiating with conservation groups for compensation for the environmental benefits ranchers create.

Read more: Opening the Range: Reforms to Allow Markets for Voluntary Conservation on Federal Grazing Lands

8. Win the Wildfire Wars

The wildfire crisis demands urgent and strategic action to restore the health of America’s forests. The department should make several reforms to improve forest restoration efficiency, scale, and outcomes.

Goal: Increase fuel treatments by 25 percent, to 3 million acres per year, to mitigate wildfire risk and improve forest health.

The United States is facing a wildfire crisis fueled by overgrown forests and exacerbated by a drier climate and longer fire seasons. In addition, barriers such as lengthy environmental review processes under the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) and frivolous litigation have impeded much-needed restoration projects.

Vast swaths of public land are now at high risk of wildfire and are in need of restoration. The consequences include catastrophic fires that destroy homes, wildlife habitats, and ecosystems and release massive amounts of pollution into the atmosphere. To address the crisis, strategic and collaborative forest restoration projects, including prescribed burning and mechanical thinning, must be quickly scaled. This will require removing bureaucratic and legal barriers and investing in proven tools to increase capacity through partnerships, like Good Neighbor Authority.

Policy Recommendations

To boost its rate of fuel treatments to 3 million acres each year, the department should:

1. Launch a cross-agency initiative to identify opportunities to accelerate the pace and scale of forest restoration projects across federal agencies: Promising areas include simplifying NEPA processes, expanding use of categorical exclusions, and integrating federal, tribal, state, and local efforts.

Read more: Does Environmental Review Worsen the Wildfire Crisis?

2. Fix the Ninth Circuit Cottonwood decision that impedes efficient forest restoration by requiring redundant analysis under the Endangered Species Act: The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service should finalize the proposed rule FWS-HQ-ES-2020-0102 from January 12, 2021, to limit consultations to projects with direct on-the-ground impacts, thereby reducing unnecessary bureaucratic delays to forest restoration without compromising protections for imperiled wildlife.

Read more: Fix America’s Forests

3. Scale up Good Neighbor Authority agreements: Good Neighbor Authority allows state, tribal, and county partners to conduct forest restoration projects on federal lands. The department should enter into more Good Neighbor agreements with local partners and highlight opportunities to do forest work and generate revenues for tribal nations through the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

Read more: Fix America’s Forests

9. Allow Tribes to Truly Manage Their Lands, Forests, and Water

Reforming policies that limit tribes’ authority over their resources will benefit tribal communities, the broader public, and environmental stewardship.

Goal: Pilot two true co-management agreements of national monuments with tribes.

Native American tribes have long-standing connections to ancestral lands, forests, and waterways, which are integral to their cultural and economic well-being. Despite this, federal policies have historically constrained tribal authority over these resources, limiting tribes’ ability to benefit from them and manage them in alignment with traditional practices. Empowering tribes to manage their lands, forests, and water is not only a matter of fairness but also a pragmatic approach to addressing pressing environmental and resource challenges.

A growing recognition of tribes’ expertise in resource stewardship presents an opportunity to recalibrate these relationships. Reforming the institutional relationship between the federal government and tribes can ensure more effective management of natural resources, addressing critical challenges like wildfire threats and water scarcity. To this end, empowering tribes to make decisions over their resources is essential for respecting tribal sovereignty and improving environmental stewardship.

Policy Recommendations

Piloting two agreements to co-manage national monuments would be a worthy short-term goal for the department, and the following reforms will empower tribes to manage even more of their resources over the long run.

1. Create co-management agreements that elevate tribal nations as equal partners in managing national monuments: These agreements should provide tribes with equal footing to influence decision-making on land use, conservation efforts, and cultural resource protection. Such agreements would ensure that tribal expertise and traditions are integral to managing these protected areas.

Read more: National Monument Alternatives: Innovative Strategies to Protect Public Lands

2. Remove federal barriers to tribal energy development: Energy resources on tribal lands could significantly boost tribal economies and improve self-sufficiency. Federal regulations, however, limit tribes’ decision-making authority and restrict their ability to benefit from resource development. Streamlining approval processes and granting tribes more control over development agreements would help unlock this potential. These reforms would empower tribes while ensuring environmentally sustainable development through self-determined regulation.

Read more: Unlocking the Wealth of Indian Nations: Overcoming Obstacles to Tribal Energy Development

3. Expand opportunities for tribal nations to restore forests: The department should support tribes in their efforts to rehabilitate and manage forest ecosystems, including through use of prescribed fire and timber management. Forging more agreements under Good Neighbor Authority will increase opportunities to restore forests on tribal lands and generate revenues for tribes. Such initiatives can strengthen tribal economies, improve forest health, and mitigate wildfire risks, while incorporating traditional knowledge into restoration practices.

Read more: Two Forests Under the Big Sky: Tribal v. Federal Management

4. Work with Congress to uniformly authorize tribes to lease water rights off reservation if they choose to do so: The department should advocate for legislative action to grant tribes clear authority to lease water rights off-reservation, enhancing their economic opportunities while respecting their water sovereignty. This flexibility will allow tribes to respond to regional water needs while ensuring their rights and priorities are upheld.

Read more: Addressing Institutional Barriers to Native American Water Marketing

5. Explore similar co-management strategies for federal lands with local communities: In many cases, local communities have been deprived of meaningful influence when it comes to managing federal lands that affect them and their economies. The department should also seek to create co-management agreements with local communities that give affected people real authority over management of federal lands, similar to Good Neighbor Authority, while retaining federal ownership of public lands.

Read more: Charter Forests: A New Management Approach for National Forests

10. Support Voluntary, Locally Led Efforts to Conserve Big-Game Migration Corridors

Private landowners are essential partners in the conservation of migrating big game. The department should recognize and support the valuable role private lands play in conserving western migrations.

Goal: Conserve the 10 highest-priority western migrations using voluntary, locally led, incentive-based approaches.

Big-game migrations across the Rocky Mountain West play vital roles in sustaining ecosystems. But they face growing threats. Growing human presence, loss of open space to development, loss of habitat connectivity due to infrastructure like fences and roads, and deteriorating forests and rangelands all threaten the future of wildlife migrations. Private agricultural lands are a cornerstone of many migration routes and are critical to ensuring their future. In the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, for example, private lands provide up to 80 percent of winter range for elk migrating out of Yellowstone National Park.

Recognizing the importance of conserving these migrations, the first Trump administration issued Secretarial Order 3362 to improve habitat quality in big-game corridors. The administration worked with states to identify priority corridors. Now, the department has the opportunity to continue working with states and landowners through voluntary, locally led, and incentive-based efforts to protect these critical habitats.

Policy Recommendations

To conserve the 10 highest-priority western migrations of big-game species, the department should:

1. Do conservation with, not to, private landowners: The department should continue to build on Secretarial Order 3362 by recognizing the importance of private lands and using voluntary, positive incentives to alleviate the costs borne by landowners. The department should also avoid formally designating and regulating migration corridors on private lands while still working with states, landowners, and the U.S. Geological Survey to identify corridors to prioritize conservation efforts.

Read more: Masters of Migration and Recognizing Private Lands For Their Public Benefits

2. Make big game an asset rather than a liability: Big-game species pose risks to landowners through fence destruction, forage consumption, and potential disease transmission. The department should work proactively with landowners, states, tribes, and private groups to make big game an asset rather than a liability through creative tools like habitat leases, occupancy agreements, payments for presence, disease mitigation, virtual fencing, and other locally generated solutions.

Read more: PERC Reports: Conservation Innovation and Developing New Tools to De-Risk Wildlife Occupancy on Private Lands

3. Leverage external resources: The department should work with private-sector companies and philanthropic organizations to establish marquee public-private partnerships in one or more landscapes, such as the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem.

Read more: The Role of Private Lands in Conserving Yellowstone’s Wildlife in the Twenty-First Century